Cuneiform exercises: signs to learn and phrases to read

This series of eight exercises gradually introduce you to a core repertoire of about 120 cuneiform signs. On each page there is a set of exercises to help you practice and test your growing understanding of cuneiform and the Akkadian language. It is important that you study each page in the order they are given here, or they will not make sense. The answers are given on separate pages.

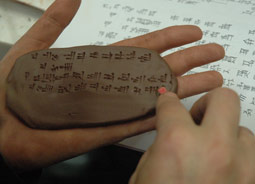

Copying cuneiform writing onto a tablet at a clay tablet workshop in September 2008, sponsored by Birkbeck College, the British Institute for the Study of Iraq, and Holborn Community Development Project. Photo by Caroline Lister. View large image.

- Exercise 1 | Answers to Exercise 1

- Exercise 2 | Answers to Exercise 2

- Exercise 3 | Answers to Exercise 3

- Exercise 4 | Answers to Exercise 4

- Exercise 5 | Answers to Exercise 5

- Exercise 6 | Answers to Exercise 6

- Exercise 7 | Answers to Exercise 7

- Exercise 8 | Answers to Exercise 8

There are three parts to each exercise: transliterating, normalising, and translating.

Transliterating

This means representing the cuneiform text alphabetically, so that it is possible to identify exactly which signs were used in the original text. In transliteration, we separate the syllabic signs of a text with hyphens, and distinguish between homophonous signs with subscript numerals. We write syllables in lower-case letters (often italics) and logograms in upper-case letters. For instance:

Cuneiform: 𒄿 𒈾 𒂍 𒃲 𒋗

Transliteration: i-na E2.GAL-šu

Professional cuneiformists use transliteration a lot. The full conventions of transliteration are described in more detail here.

Normalisation

Normalisation (or transcription) means representing the Akkadian language alphabetically, including details like vowel-length and doubled consonants that the cuneiform script itself doesn't always represent. In normalisation it is not possible to see which cuneiform signs were used to write the original text. Normalised Akkadian is usually written in italic script. For instance:

Cuneiform: 𒄿 𒈾 𒂍 𒃲 𒋗

Transliteration: i-na E2.GAL-šu

Normalisation: ina ēkallišu

Akkadian dictionaries, textbooks, and reference grammars all use normalisation. Often normalisation can help you do choose the correct reading of an ambiguous sequence of signs.

Translation

Because Akkadian and English word-order are so different, it is not always possible to translate a cuneiform text word-for-word. When an Akkadian word has a wide range of meanings, or is not well understood, we have to give alternative translations, or show (with question-marks or italics) that our translation is uncertain. For instance:

Cuneiform: 𒄿 𒈾 𒂍 𒃲 𒋗

Transliteration: i-na E2.GAL-šu

Normalisation: ina ēkallišu

Translation: In (or: from) his palace

Every cuneiformist has a slightly different translation style. The more cuneiform and Akkadian you know, the better you can judge the accuracy and sensitivity of other people's translations.

Content last modified on 09 Apr 2024.

Eleanor Robson

Eleanor Robson, 'Cuneiform exercises: signs to learn and phrases to read', Knowledge and Power, Higher Education Academy, 2024 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/saao/knpp/CuneiformRevealed/Learningsigns/Cuneiformexercises/]