Esagil (temple of Marduk at Babylon)

Babylon's principal temple was Esagil (also commonly referred to as Esagila and Esangil), which was dedicated to that city's tutelary deity Marduk, and it was located in East Babylon, inside the sacred Eridu district, south of the ziggurat Etemenanki, and west of the Processional Way Ay-ibūr-šabû. The remains of this large, once-grand, 15,350-m² religious structure now lay under modern Tell Amran (Tell Omran), the second-highest mound of ruins in Babylon. Esagil, at least according to one first-millennium-BC hierarchical list of temples, was the third most important temple in Babylonia, after Ekur (the temple of the god Enlil in Nippur) and Ebabbar (the temple of the sun-god Šamaš in Sippar).

A.R. George's hand-drawn facsimile of VAT 17115, a clay tablet inscribed with a text called the "Explanation of Temples Names in Babylon D" or the "Esagil Commentary." Reproduced from A.R. George, Babylonian Topographical Texts, pl. 20.

Names and Spellings

Babylon's principal temple went by the Sumerian ceremonial name Esagil, which means "House Whose Top Is High." That name is well attested in cuneiform sources of the first and second millennia BC. Some texts explaining the names of religious buildings, including the so-called "Götteradressbuch von Assur" (Divine Directory of Ashur), translate Sumerian Esagil as Akkadian bītu ša rēšāšu šaqâ and bītu našâ rēši. A text sometimes referred to as the "Explanation of Temples Names in Babylon D" gives about thirty different explanations for the Sumerian name of Marduk's temple.

- Written Forms: é-sa-ág-gi-il; é-sa-ág-gil; é-sa-an-gi-íl; é-sa-an-gíl; é-sá-gil; é-sa₄-an-gil; é-sa₄-ki-il; é-sa₆-an-gil; é-sa₇-kìl; é-sa₁₂-an-aga-íl; é-sa₁₂-an-gil; é-sag-gil; é-sag-gíl; é-sag-íl; é-sag-íl-la; é-sag-ìl-la; é-saŋ-íl-la-ke₄; é-si-an-gíl; é-sì-an-ki-il.

Known Builders

- Old Babylonian (ca. 1900–1600 BC)

- Sābium (r. 1844–1831 BC)

- Neo-Assyrian (ca. 911–612 BC)

- Esarhaddon (r. 680–669 BC)

- Ashurbanipal (r. 668–ca. 631 BC)

- Neo-Babylonian (ca. 625–539 BC)

- Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 604–562 BC)

- Neriglissar (r. 559–556 BC)

- Nabonidus (r. 555–539 BC)

- Hellenistic (323–63 BC)

- Antiochus I Soter (r. 281–261 BC)

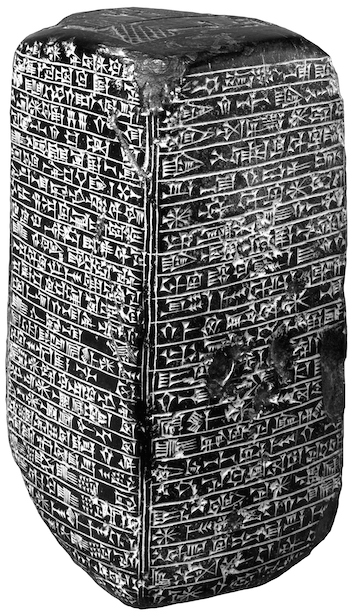

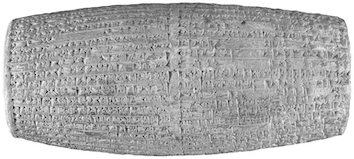

BM 091027, Lord Aberdeen's Black Stone. This cuboid-shaped monument of the Assyrian king Esarhaddon records his rebuilding of Babylon and Esagil. Image adapted from the British Museum Collection website. Credit: Trustees of the British Museum.

Building History

Although the earliest-attested reference to a Marduk temple at Babylon (BAR.KI.BAR) comes from the late third millennium BC, it is not until the Old Babylonian Period that any information about the building history of Esagil comes to light. Due to the high level of the groundwater at Babylon — which makes it impossible to investigate the occupation levels and building phases earlier than the Neo-Babylonian Period — most of the details from this period of time come from cuneiform sources discovered outside of Babylon. Some information about work on and sponsorship of Marduk's temple during the First Dynasty of Babylon is known from year names of several of its kings. Sābium, the third king of the "Hammu-rāpi Dynasty," is the only ruler from that period who is known to have renovated Esagil; this took place during his tenth regnal year (1835 BC). Five other kings of this dynastic line (Sūmû-la-El, Hammu-rāpi, Ammī-ditāna, Ammī-ṣaduqa, and Samsu-ditāna) are known to have patronized Marduk's temple, principally by contributing different objects (statues, weapons and emblems).

Despite the fact that nothing is known about Esagil's building history from the end of the First Dynasty of Babylon until the reign of the seventh-century-BC Assyrian king Esarhaddon, it is sometimes assumed that Nebuchadnezzar I (r. 1125–1104 BC), the fourth ruler of the Second Dynasty of Isin, rebuilt or renovated Babylon's principal temple because that Babylonian ruler is known to have restored the statue of Marduk to its rightful place after it had been carried off to the Elamite capital Susa and to have made Marduk the most important god in the Babylonian pantheon. Given the lack of textual and archaeological evidence, this assumption cannot be confirmed with any degree of certainty.

In 689 BC, the Assyrian king Sennacherib (r. 704–681 BC) captured, looted, and destroyed Babylon, including Esagil and its ziggurat Etemenanki. Although the actual destruction was probably not as bad as that ruler described in his royal inscriptions (especially in the so-called "Bavian Inscription"), Babylon, with the god Marduk's temple at its heart, ceased to be the bond that linked heaven and earth. That connection was severed when Esagil had been destroyed and when Marduk's statue and its paraphernalia had been carried off to Assyria and placed in Ešarra ("House of the Universe"), the temple of the Assyrian national god Aššur at Ashur (modern Qalat Sherqat). His son Esarhaddon, the first-known Assyrian builder of this temple of Marduk, started restoring Esagil soon after ascending the throne. One of his inscriptions described the project as follows:

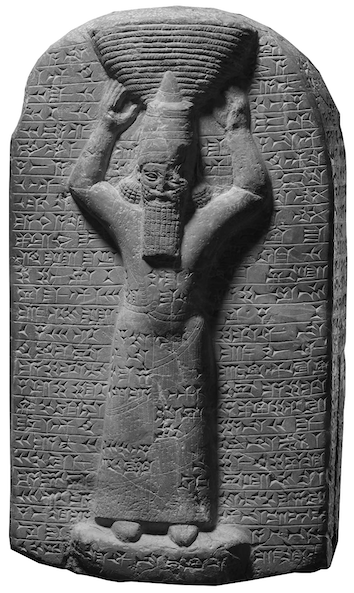

BM 090864, a marble stele depicting Ashurbanipal carrying a basket on his head and recording that king's restoration of Ekarzagina, the temple of the god Ea in the Esagil complex. Image adapted from the British Museum Collection website. Credit: Trustees of the British Museum.

While construction in Babylon was taking place, Esarhaddon had skilled craftsmen restore the damaged divine statues of Marduk and his entourage (Beltiya [Zarpanitu], Belet-Babili [Ištar], Ea, and Mandanu) and had several cult objects fashioned; this careful work took place in an appropriate workshop at Ashur. Despite Esarhaddon's best efforts, and contrary to what his inscriptions recorded, work on Esagil remained unfinished and the refurbished statue of Marduk remained in Assyria when he died in late 669 BC. The completion of that work fell to his two sons Ashurbanipal, who became the king of Assyria, and Šamaš-šuma-ukīn, who became king of Babylon (r. 667–648 BC).

Although his older brother Šamaš-šuma-ukīn was the king of Babylon, Ashurbanipal took it upon himself to complete his recently-deceased father's unfinished business, starting with returning the statues of Marduk and his entourage to their rightful places in Babylon. According to Akkadian inscriptions written on clay cylinders and stone steles, Ashurbanipal finished Esagil's structure; refurbished all of its many shrines, platforms, and daises; adorned its interior, especially the cella Eumuša ("House of Command"), which he "made glisten like the stars of the firmament"; roofed it with cedar and cypress beams transported from the Levant; hung wooden doors in its (principal) gateways; and donated numerous objects for the cult. In the cella, the holiest room of the temple, Ashurbanipal's workmen created an entirely new throne-dais from bricks cast from a vast quantity a silver alloy called zahalû. Once the work was completely finished, Esagil once again became a universal bond that linked heaven and earth, just as it had been before his grandfather Sennacherib severed it. For the duration of his long reign, Ashurbanipal continued to actively support Esagil and its cults, despite the fact that he was not the king of Babylon.

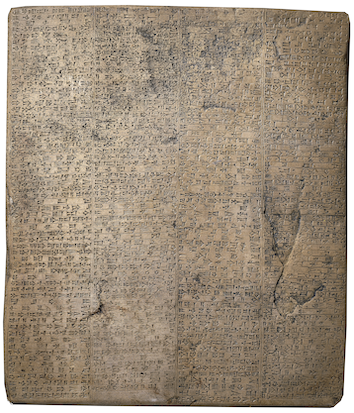

BM 129397, a large stone tablet that bears a long Akkadian inscription that is now commonly referred to as the "East India House Inscription." The description of Nebuchadnezzar's decoration and roofing of Marduk's cella is recorded in lines ii 36–iii 35. Image adapted from the British Museum Collection website. Credit: Trustees of the British Museum.

As is typical for Babylon, as well as other cities like Borsippa and Sippar, most of the information that survives today about construction on Esagil comes from the Neo-Babylonian Empire (ca. 625–539 BC), mostly from the reign of its second and most famous ruler, Nebuchadnezzar II. This comes as no surprise since Marduk's temple was Babylon's most important building and it would have been astoundingly that Nebuchadnezzar would not have sponsored construction on it while he was transforming his capital into a wonder to behold. Bricks bearing inscriptions of his used to pave the floors (see below) attest to this king's work on Esagil's structure. This is significant because the most-descriptive accounts of work on Marduk's temple in Nebuchadnezzar's inscriptions generally record that ruler's decoration of the interior rooms, especially Marduk's cella Eumuša, which he also had reroofed. One of the longest, presently-known descriptions of this king's work on Marduk's temple is found in an Akkadian inscription written on a large stone tablet. The relevant passage of the so-called "East India House Inscription" reads:

Presumably, Nebuchadnezzar also had a protective, subterranean base (Akkadian kisû) constructed around Esagil using baked bricks (Akkadian agurru) and bitumen (Akkadian kupru), as he did with other temples at Babylon.

Loan Ant-43, a two-column clay cylinder purchased at Babylon by Sir John Malcolm ca. 1811 and now on display in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. The Akkadian inscription written on it records the manufacture of copper mušhuššu-dragons for a few prominent gateways of Marduk's temple Esagil. Credit: Fitzwilliam Museum.

During his short, three-year reign, Neriglissar — an influential and wealthy landowner who married one of Nebuchadnezzar II's daughters (possibly Kaššaya) and later became king — sponsored renovation on parts of Marduk's temple. Akkadian inscriptions of his written on clay cylinders record that he rebuilt the northern enclosure wall of the temple complex and stationed statues of mušhuššu-dragons in the gates Ka-Utu-e, Ka-Lamma-arabi, Ka-ḫegal, and Ka-ude-babbar, Esagil's most important entranceways. Nabonidus, Babylon's last native king, claims that he also renovated and refurbished some of the principal gateways of Esagil, including the entrances of the "main courtyard," principally by providing them with new wooden doors and by refurbishing their mušhuššu-dragon and goat-fish (Akkadian suhurmāšu) statues.

The last-attested builder of Esagil from presently-extant cuneiform sources is the Seleucid ruler Antiochus I Soter. This ruler's work on the Marduk temple is recorded in an Akkadian inscription written on a two-column clay cylinder. The relevant passage of that text reads:

According to an Astronomical Diary entry, some of this work took place during the year 274 BC, when Antiochus had unbaked mudbricks (Akkadian libittu) molded upstream and downstream of Babylon in order to rebuild Esagil.

Although Marduk's cult remained in use until ca. 300 AD, nothing of Esagil's building history is known after Antiochus I had it rebuilt. However, it is clear from texts in the archive of the banker Rahimesu and related texts (ca. 90 BC) that Esagil was in desperate need to repairs in the Parthian Period.

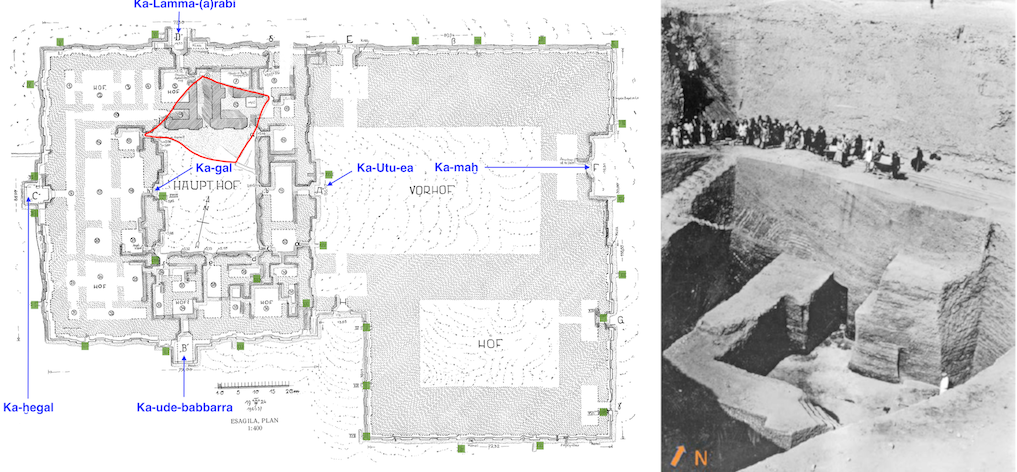

Annotated plan of Esagil showing the deep 20×20-meter pit (outline in red) and the smaller pits dug around the perimeter of the temple (green), as well as the proposed locations of the temple's most important gateways (blue) (left); and an excavation photo of the pit dug into the courtyard and Rooms 6 and 12 taken in October 1900 (Babylon Photo 86). Adapted from F. Wetzel, Das Hauptheiligtum des Marduk in Babylon, Esagila und Etemenanki pl. 3. Photograph credit: SMB Vorderasiatisches Museum, Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft.

Archaeological Remains

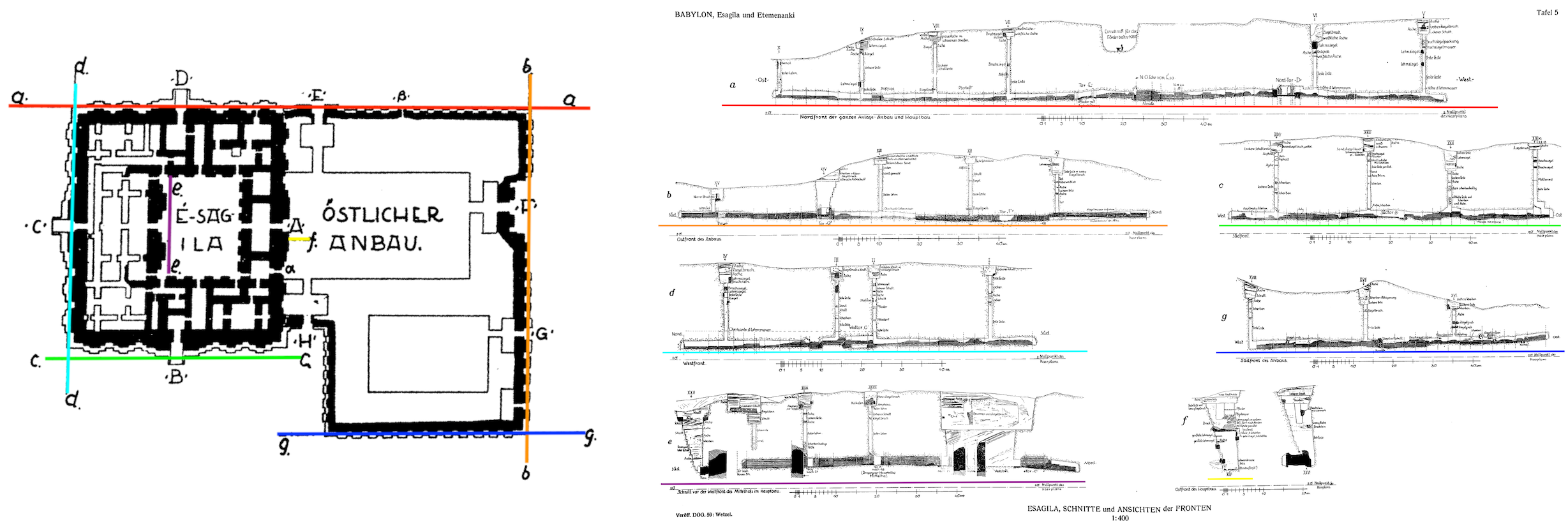

The remains of Esagil, which are buried deep under modern Tell Amran, have been partially excavated by the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft (DOG) and Königliche Museen Berlin (KMB) in 1899–1917, first under the direction of Walter Andrae in 1900 and by Friedrich Wetzel and Klaus Müller in 1910–11. Only a small portion of this large 15,350-m² temple has been investigated. Andrae's large and deep 20×20-meter pit (dug to a depth of 20 meters) exposed the northern section of the main courtyard (Court of Bēl) and a few of the rooms north of it, while Wetzel and Müller's 29 or 30 smaller pits (which were often only 1 m wide at the bottom) and tunnels dug between the bottom of those shafts revealed the exterior plan of the temple, as well as layout of some of the walls around the main courtyard and the forecourt (Lower Court). There were almost no excavations made inside Esagil's rooms. The main part of the temple — which was square in shape and thus resembled its celestial counterpart, the constellation known to the Babylonians as the "Field" (Akkadian ikû) and to us as the "Square of Pegasus" — measured 6,180 m² and the eastern annex building covered an area of 9,170 m². The main courtyard is approximately 1,120 m². The size of Marduk's cella (Eumuša; Room 17), however, is unknown because it has not been excavated. Although there are references to work on Marduk's temple from the Old Babylonian Period onwards, secure archaeological evidence begins only with the late Neo-Assyrian Period. As is typical with other buildings in Babylon, there is a lot of archaeological remains from the Neo-Babylonian Period, especially from the long reign of Nebuchadnezzar II.

Annotated plans of Esagil showing the pits and trenches pits dug into and around Esagil in 1910–11. Adapted from F. Wetzel, Das Hauptheiligtum des Marduk in Babylon, Esagila und Etemenanki pls. 2 and 5.

The main part of Esagil, which housed the holiest rooms of the temple, had a double foundation platform constructed of unbaked brick; Esagil is the only known temple at Babylon to have been placed on such a platform. The inner walls — which were ca. 3.0 m thick and preserved to a height of 5.4 m above the highest-preserved floor — were built on top of the foundation platform. The precise relationship of the outer walls, which were 6–8.3 m thick, to the foundation platform, however, is not yet known. The outer walls of the main building were surrounded by an underground 2-m-thick baked-brick base (Akkadian kisû), were buttressed, and had tower-flanked entranceways (Gates A–D); the door leading to Marduk's cella (Gate h) also had towers on both sides of it. The walls, which were made of unbaked brick, were coated with a whitish lime-gypsum plaster. It has recently been estimated that 6,400,700 unbaked bricks were used to construct the main part of Esagil, assuming that the external walls were built to a towering height of 16.5 m.

Remains of seven floor levels were exposed in the 20×20-m pit and in some of the tunnels. Floors l and k (Levels 3 and 4) date to the Neo-Assyrian Period since they have bricks of Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal built into them. Floor h and g (Levels 5 and 6) were laid by the Neo-Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II, as evident from the bricks bearing inscriptions of his. The earlier Floors m and n (Levels 1 and 2) and the later Level 7 Floor lack inscriptions so their exact dates of execution are unknown. The floors of the temple had black bitumen covering the baked brick. The baked-brick floors of the courtyards, however, were not coated with bitumen.

Because only the external façades of eastern annex building were traced by means of shafts and tunnels, with no excavations carried out inside it, virtually nothing is known about that large part of Esagil. It is certain, however, that the temple's principal entrance was Gate F, which was located in the eastern wall and about 30 m south of the northeast corner of the building, and that Gate A, which was located on the western side of a rectangular-shaped courtyard, provided access to the main temple from that part of building.

Further Reading

- George, A.R. 1992. Babylonian Topographical Texts (Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 40), Leuven, pp. 294–298, 382–409, and 414–440.

- George, A.R. 1993. House Most High. The Temples of Ancient Mesopotamia (Mesopotamian Civilizations 5), Winona Lake, pp. 139–140 no. 967.

- George, A.R. 1995. "The bricks of E-sagil," Iraq 57, pp. 173–197.

- Koldewey, R. 1911. Die Tempel von Babylon und Borsippa (Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 15), Leipzig, pp. 37–49 and pls. 7–10.

- Koldewey, R. 1990. Das wieder erstehende Babylon, fifth edition (edited by B. Hrouda), Munich, pp. 201–211.

- Pedersén, O. 2021. Babylon: The Great City, Münster, pp. 142–153.

- Wetzel, F. 1938. Das Hauptheiligtum des Marduk in Babylon, Esagila und Etemenanki (Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichung der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 59), Leipzig, 1–13 and pls. 1–5.

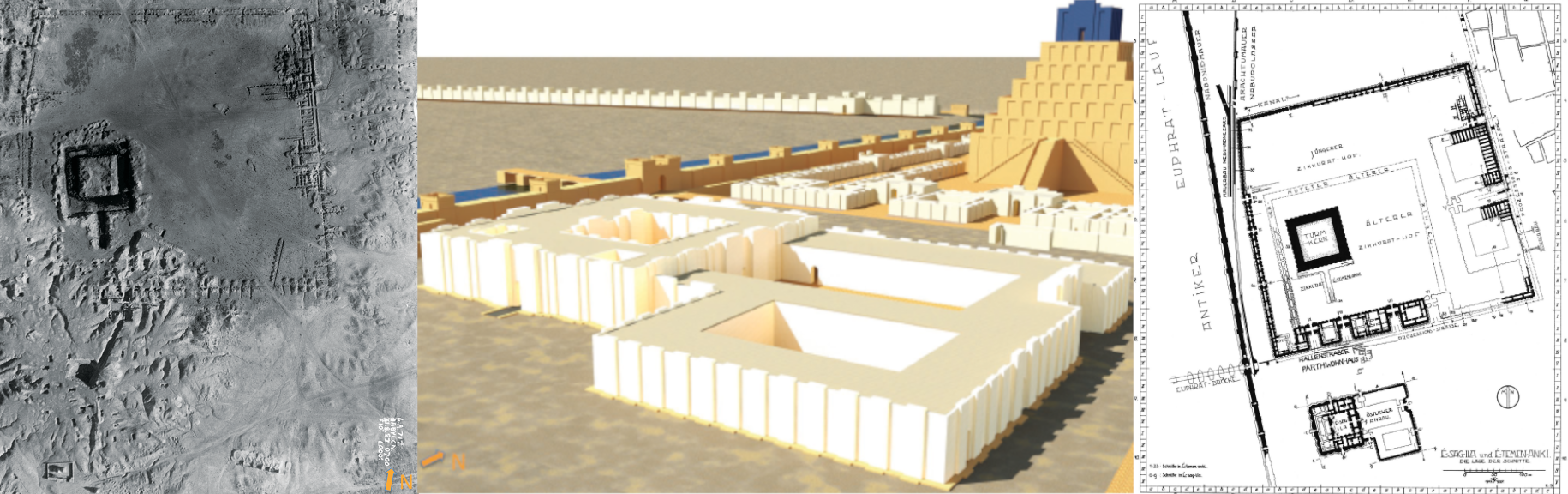

Banner image: areal photograph of the excavation pits and trenches in the area of the remains of Esagil and Etemenanki taken in 1923 (left); a reconstruction of Esagil and Etemenanki during the reign of the Neo-Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II (center); a plan of Esagil, and Etemenanki (right). Images from O. Pedersén, Babylon: The Great City, pp. 144–145 figs. 4.3–4.4 and p. 151 fig. 4.11.

Jamie Novotny

Jamie Novotny, 'Esagil (temple of Marduk at Babylon)', Babylonian Temples and Monumental Architecture online (BTMAo), The BTMAo Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, [http://oracc.org/btmao/Babylon/TemplesandZiggurat/Esagil/]