Ebabbar (temple of Šamaš at Sippar)

The sun-god's temple at Sippar is one of the best-known and well-attested Babylonian religious structures. According a first-millennium-BC hierarchical list of temples, Ebabbar was the second most important temple in Babylonia, after Ekur (the temple of the god Enlil in Nippur); it was ranked even higher than Esagil (the temple of the god Marduk in Babylon).

Names and Spellings

Sippar's principal temple went by the Sumerian ceremonial name Ebabbar(ra), which means "Shining House"; that name is also attested for other temples of the sun-god Šamaš, including that deity's temples in Larsa (modern Tell as-Senkereh) and Ashur (modern Qalat Sherqat).

- Written Forms: e₂-babbar; e₂-babbar-ra.

Known Builders

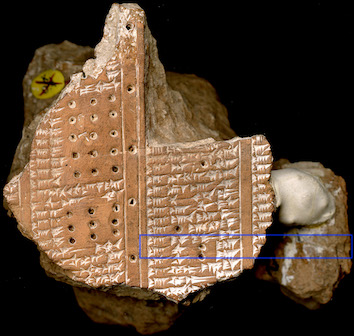

Obverse of K 15202 + Sm 289, a fragment of a multi-column clay tablet inscribed with a copy of the "Canonical Temple List." Col. iii line 12´ mentions the Ebabbar temple at Borsippa. Image adapted from the CDLI.

- Old-Akkadian (ca. 2340–2200 BC)

- Narām-Sîn (r. 2254–2218 BC)

- Old-Babylonian (ca. 1900–1600 BC)

- Sābium (r. 1844–1831)

- Samsu-iluna (r. 1749–1712 BC)

- Middle Babylonian (ca. 1500–1100 BC)

- Kurigalzu I

- Neo-Assyrian (ca. 911–612 BC)

- Ashurbanipal (r. 668–ca. 631 BC)

- Šamaš-šuma-ukīn (r. 667–648 BC)

- Neo-Babylonian (ca. 625–539 BC)

- Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 604–562 BC)

- Nabonidus (r. 555–539 BC)

Building History

At present, there is no contemporary archaeological or textual evidence for the Ebabbar temple in the late-third millennium BC. Building activities of Old Akkadian kings at Sippar, however, are recorded in Akkadian royal inscriptions of Nabonidus, the last native king of Babylon. In these much-later texts, some of which were found in the ruins of the temple, that sixth-century-BC Babylonian ruler states that his workmen had found Ebabbar's original foundations, which were purportedly laid by the then-famous Narām-Sîn, the fourth king of the Dynasty of Agade and grandson of the equally-renowned Sargon of Agade (r. 2334–2279 BC). Although there are no contemporary inscriptions of Narām-Sîn recording his work on Ebabbar, there is some Old-Akkadian-Period evidence of the kings of Agade and their immediate family patronizing the sun-god's temple at Sippar. For example, a short inscription of Šu-Enlil, a son of Sargon, was found near the ziggurat Ekunankuga (in a Neo-Babylonian layer), several votive offerings for Šamaš were made by members of the Akkadian royal family, and Narām-Sîn installed his daughter, the princess Šumšanī, as Šamaš' high-priestess (Akkadian entu). Thus, it is highly likely that at least one of the kings of Agade, possibly even Narām-Sîn as Nabonidus claims in his inscriptions, sponsored construction on the Ebabbar temple at Sippar.

The first contemporary evidence for Ebabbar's building history dates to the Old Babylonian Period, from the reigns of Sābium and Samsu-iluna, the third and seventh rulers of the First Dynasty of Babylon. Construction on this important temple is mentioned in two year names — the eighth regnal year of Sābium (1837 BC) and Samsu-iluna's eighteenth year as king (1732 BC) — and in Sumerian and Akkadian royal inscriptions of Samsu-iluna, the son and immediate successor of Hammu-rāpi (r. 1792–1750 BC). Those sources provide no details about the work itself. Ammī-ṣaduqa, the tenth and penultimate ruler of the First Dynasty of Babylon, might have also made repairs to Ebabbar in or after his seventeenth year as king (1630 BC) since he is known to have renovated Sippar's ziggurat Ekunankuga.

During the Kassite rule over Babylonia, one of the Kurigalzus, probably the first of the two kings with that name, renovated Ebabbar, as is evident from an inscription written on a brick found at Sippar. As is typical with texts inscribed or stamped on bricks, no details about Kurigalzu's rebuilding of the Šamaš temple are provided.

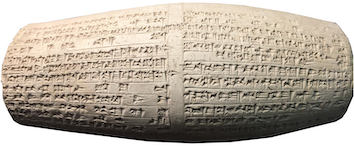

BM 091101, a two-column clay cylinder with an Akkadian inscription recording Nebuchadnezzar II's rebuilding of Ebabbar at Sippar. Photo: Frauke Weiershäuser.

After a very long gap, information about Ebabbar's building history resumes again in the seventh century BC, during the contemporaneous reigns of Assyria's last great king, Ashurbanipal, and his older brother Šamaš-šuma-ukīn, the king of Babylon. Few details about these rulers' work on Šamaš' temple are recorded in the two known texts from this time commemorating Ebabbar's renovation. Ashurbanipal, in an Akkadian text written on clay cylinders, states that he sought the building's original emplacement, while Šamaš-šuma-ukīn, in a Sumerian text on bricks, records that he had the temple's superstructure constructed with baked bricks. The work was carried out by these two sons of Esarhaddon (r. 680–669 BC) between 668 BC and 652 BC.

As with the temples at Babylon, most of the information that survives today about Sippar's temples comes from the Neo-Babylonian Period. Numerous Akkadian inscriptions of Nebuchadnezzar II and Nabonidus attest to a period of intense building within the Ebabbar precinct during the reigns of those two kings; Nebuchadnezzar's father Nabopolassar (r. 625–605 BC) — the founder of the Neo-Babylonian Empire — and Neriglissar (r. 560–556 BC) — an influential and wealthy landowner who married one of Nebuchadnezzar's daughters (possibly Kaššaya) and later became king — also sponsored building at Sippar, but mainly on the ziggurat, at least according to presently-extant sources.

Although numerous inscriptions of Nebuchadnezzar II written on clay cylinders and baked bricks record that he had the sun-god's temple at Sippar rebuilt, few texts of his provide any details about that project. In an inscription on double-column clay cylinders, Nebuchadnezzar claims that he had Ebabbar constructed on its ancient foundations, built exactly as it had been in the past, and to have made it "shine like daylight." A text known from bricks also states that he had a protective, subterranean base (Akkadian kisû) constructed around the building using baked bricks (Akkadian agurru) and bitumen (Akkadian kupru); this feature is well attested archaeologically for temples built at Babylon during Nebuchadnezzar's long reign. After construction came to an end, the divine statue of Šamaš was brought back into his temple and placed upon his dais during a joyous celebration.

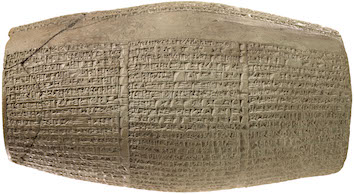

VA 02536, a three-column clay cylinder that is inscribed with the so-called "Ehulhul Cylinder Inscription" of Nabonidus. Ebabbar's reconstruction is recorded in detail in cols. ii–iii. © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Vorderasiatisches Museum. Photo: Olaf M. Teßmer.

The most detailed descriptions about work on Ebabbar date to the time of Nabonidus. No less than ten Akkadian inscriptions of that Neo-Babylonian king written on clay cylinders record many of the details of his long and extensive rebuilding of this temple of Šamaš. Those accounts include information about every stage of construction, from start to finish, and, in typical Mesopotamian fashion, those texts narrate events in a manner that is more concerned with royal ideology rather than historical reality. Thus, according to these self-aggrandizing reports, Nabonidus had Ebabbar completely rebuilt anew since the temple constructed by Nebuchadnezzar II forty-five years earlier had (prematurely) collapsed, something that had happened because that ruler failed to construct the temple on its original, divinely-approved foundations. After receiving divine confirmation through favorable responses to questions posed through extispicy and after much time and effort searching the ruins of the (allegedly) collapsed temple, Nabonidus' specialists from Babylon and Borsippa claim to have discovered the earliest foundation, the ones purportedly laid by the Old Akkadian king Narām-Sîn. So not to incur the anger of the sun-god, the king's workmen were instructed to lay Ebabbar's new foundations precisely over the ancient foundations, "not (even) a fingerbreadth outside or inside (of them)." Once that arduous task had been accomplished, the new mudbrick superstructure was built, 5,000 beams of cedar were stretched out as its roof, new wooden doors were hung in its prominent gateways, and the most important rooms of the temple were lavishly decorated.

Although Ebabbar remained in use after the Neo-Babylonian Period, nothing is known about its post-Nabonidus building history.

Archaeological Remains

The Ebabbar precinct, which measures approximately 310×240 m, is located in the southwest part of city. The substantial ruins of the temple, together with the ziggurat Ekunankuga, have been excavated principally by Hormuzd Rassam (1881–82) and the University of Baghdad team led by Walid Al-Jadir (1978–). Rassam excavated roughly 150 rooms in the temple complex, including the cella of Šamaš (Room 168, which included the square-shaped dais upon which the sun-god's statue stood). A further fifty rooms and two courtyards were unearthed by Iraqi archaeologists; although this cannot be confirmed with certainty, that part of the Ebabbar complex was likely the temple of the goddess Aya, Šamaš' consort.

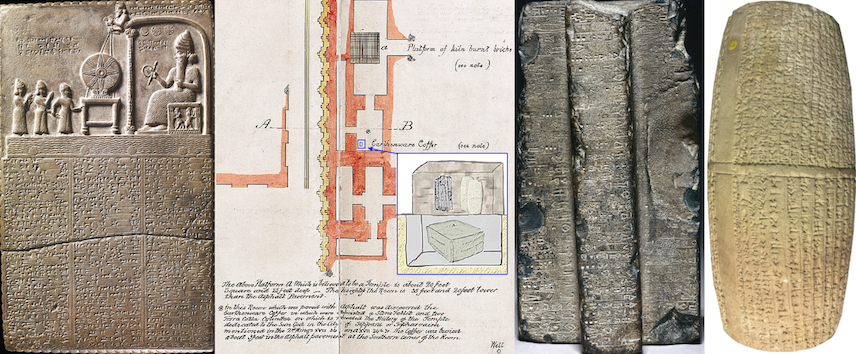

Discoveries in Room 170 of Ebabbar (from left to right): the "Sun-God Tablet" of the Babylonian king Nabû-apla-iddina; location of the fired-brick box and the clay coffer in Room 170 according to a plan of "Aboo-Habba or Sipara" drawn by H. Rassam; the "Cruciform Monument of Man-ištūšu"; and a clay cylinder of Nabonidus (BM 91140). Image created by Jamie Novotny from I. Finkel and A. Fletcher, "Thinking outside the Box: The Case of the Sun-God Tablet and the Cruciform Monument," Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 375 (2016) figs. 1a, 4 and 11–12; and a photograph taken by F. Weiershäuser.

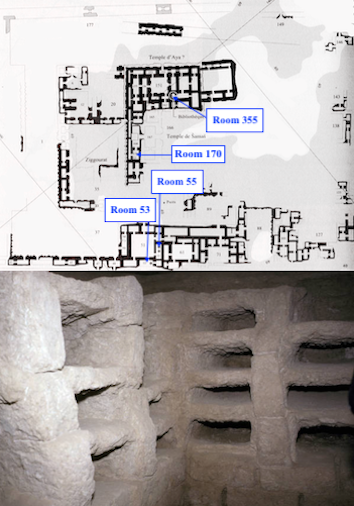

Plan of the Ebabbar temple precinct showing the location Rooms 53, 55, 170 and 355 (top); and photograph of the niches in Room 355, in which about 800 clay tablets were stored (bottom). Plan adapted from Reallexikon der Assyriologie 12/7–8 p. 540 Fig. 3. Excavation photograph by Jean-Luc Manaud/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images.

In the southeast corner of Room 170, a chamber directly south of Šamaš' cella, Rassam made a remarkable discovery: just three feet below the floor's surface was a clay coffer with a large, gray schist tablet and several clay impressions of the bas-relief portion of the tablet. That 29.5×17.8-cm tablet — whose upper third includes a anthropomorphic depiction of Šamaš seated beneath symbols of the sun, moon, and the planet Venus — is the now-famous "Sun-God Tablet" of Nabû-apla-iddina. In addition, just above the casket, in situ on the bitumen floor of Room 170, Rassam's workmen found a box of fired bricks containing two clay cylinders of Nabonidus and a cruciform-shaped monument bearing an Akkadian text of the Sargonic ruler Man-ištūšu (r. 2269–2255 BC); the so-called "Cruciform Monument of Man-ištūšu" is generally considered to be a creation of sixth-century-BC Babylonian scribes, rather than a genuine late third-millennium-BC monument.

Rassam's excavations also unearthed approximately 35,000 clay tablets at Sippar. Most of the cuneiform documents found in Ebabbar, where the main libraries of the city were situated, come from Rooms 53 and 55, chambers accessed from Courtyard 51. In 1985–86, Iraqi excavations under the direction of Al-Jadir discovered a library in Room 355, a chamber that was likely part of the temple of the goddess Aya. Nearly 800 clay tablets were found in situ in 56 well-preserved niches. The texts in that archival repository date to the Neo-Babylonian and Achaemenid periods, at least until the reign of Cambyses II (r. 529–522 BC).

Further Reading

- Baker, H.D. and Jursa, M. 2011. "Sippar. A. II. Im 1. Jahrtausend," Reallexikon der Assyriologie 12/7–8, pp. 533–537.

- Frayne, D.R. 1990. Old Babylonian Period (2003–1595 BC) (Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia, Early Periods 4), Toronto, pp. 374–378 no. E4.3.7.3.

- Gasche, H. and Tanret, M. 2011. "Sippar. B. Archäologisch," Reallexikon der Assyriologie 12/7–8, pp. 537–547.

- George, A.R. 1993. House Most High: The Temples of Ancient Mesopotamia (Mesopotamian Civilizations 5), Winona Lake, p. 70 no. 97.

- Jiménez, E. 2013. "Cities and Libraries," Cuneiform Commentaries Project (E. Frahm, E. Jiménez, M. Frazer, and K. Wagensonner), https://ccp.yale.edu/introduction/cities-and-libraries. DOI: 10079/m37pw09.

- Kalla, G. 2011. "Sippar. A. I. Im 3. und 2. Jahrtausend," Reallexikon der Assyriologie 12/7–8, pp. 528–533.

Banner image: schematic topographical map of Sippar (left); photo from the excavations of the library at Sippar in March 1989 (center); plan of the Ebabbar temple precinct (right). Drawings adapted from Reallexikon der Assyriologie 12/7–8 pp. 539–540 Figs. 2–3. Excavation photograph by Jean-Luc Manaud/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images.

Frauke Weiershäuser, Jamie Novotny & Joshua Meynell

Frauke Weiershäuser, Jamie Novotny & Joshua Meynell, 'Ebabbar (temple of Šamaš at Sippar)', Babylonian Temples and Monumental Architecture online (BTMAo), The BTMAo Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, [http://oracc.org/btmao/Sippar/Ebabbar/]