Etemenanki (ziggurat of Marduk at Babylon)

Etemenanki, Babylon's ziggurat, was situated in the Eridu district of Babylon (modern Sahn), on the east bank of the Arahtu River. The high temple-tower, which was erected inside a 400×400-meter walled precinct, was built west of the Processional Way and north of Babylon's principal temple, Esagil. Little of this once-towering, multi-stage building remains today.

Names and Spellings

In a composition often referred to as the "Collection of Sumerian Temple Hymns," the name Etemenanki is used as an epithet or byname of the ziggurat Eunir at Eridu (modern Tell Abu Shahrain), one of the earliest-built cities in southern Mesopotamia. This Sumerian ceremonial name, which means "House, Foundation Platform of Heaven and Underworld," first appears in connection with Marduk's temple-tower in the seven-tablet Babylonian epic of creation Enūma eliš, the five-tablet scholarly compendium Tintir = Babylon, and the five-tablet Poem of Erra. The earliest-known royal inscription mentioning Babylon's ziggurat is surprisingly late: the Bavian Inscription of the Neo-Assyrian king Sennacherib (r. 704–681 BC). The name Etemenanki, however, does not appear in that genre of texts until the reign of that ruler's son and successor, Esarhaddon (r. 680–669 BC), who records its rebuilding after its destruction in 689 BC.

- Written Forms: e₂-te-me-an-ki; é-te-me-en-an-ki; é-te-mén-an-ki; é-temen-an-ki; e₂-temen-me-an-ki.

Known Builders

- Neo-Assyrian (ca. 911–612 BC)

- Esarhaddon (r. 680–669 BC)

- Ashurbanipal (r. 668–ca. 631 BC)

- Neo-Babylonian (ca. 625–539 BC)

- Nabopolassar (r. 625–605 BC)

- Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 604–562 BC)

Building History

Information about Etemenanki prior to the Assyrian domination of Babylonia (728–626 BC) is very sparse and comes entirely from works of literature (Enūma eliš, Poem of Erra) and scholarly compilations (Tintir = Babylon) and, thus, it is not entirely certain when Marduk's ziggurat at Babylon was founded. It has often been suggested that Nebuchadnezzar I (r. 1125–1104 BC), the fourth ruler of the Second Dynasty of Isin, was its founder; this would coincide with the period during which Enūma eliš is generally thought to have been composed. Given the lack of textual and archaeological evidence, this assumption cannot be confirmed with any degree of certainty and one cannot rule out the possibility that Etemenanki was founded much early, perhaps even in the Old Babylonian Period.

The late Neo-Assyrian king Esarhaddon (r. 680–669 BC) is the first known builder of Marduk's ziggurat. He restored Etemenanki, together with Esagil and other temples at Babylon, after his father Sennacherib (r. 704–681 BC) had its bricks and earth removed and thrown into the Arahtu River in 689 BC. This de facto ruler of Babylon records that he rebuilt Etemenanki on its former site, which he states was one ašlu and one ṣuppān in length and width (approximately 90 m). Esarhaddon died before completing the work and his son, Ashurbanipal (r. 668–ca. 631 BC), finished the job, despite the fact that his older brother Šamaš-šuma-ukīn (r. 667–648 BC) was king of Babylon at the time.

At the start of the Neo-Babylonian Empire (625–539 BC), Etemenanki was in need of repair. Nabopolassar (r. 625–605 BC), who had put an end to the Assyrian domination in Babylonia, started the long process of reconstruction. By the time of his death in 605 BC, Nabopolassar's workmen had raised the outer, baked-brick covering of the ziggurat's first terrace to a height of 15 m (30 ammatu). During his forty-three-year-long reign, Nabopolassar's son and immediate successor Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 604–562 BC) completed the construction of Etemenanki in its entirety; labor was provided by people from the then-far-reaching Babylonian Empire. In addition to raising the first terrace an additional 15 m, Nebuchadnezzar had his workmen construct the upper terraces and a temple whose exterior façade was built of blue-glazed bricks. The multi-staged ziggurat appears to have been built as a twin of the god Nabû's temple-tower at Borsippa, Eurmeiminanki ("House Which Gathers the Seven of Heaven and Underworld"), which also had a blue-glazed temple erected on top of it. At the time of its completion, this lofty structure is estimated to have been constructed from about 10,300,000 mudbricks and 30,200,000 baked bricks.

Little is known about the history of Etemenanki after the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II. Classical sources seem to infer that the Persian king Xerxes I (r. 485–465 BC) (partially) destroyed Marduk's ziggurat when he crushed a revolt in Babylon. One of the Hellenistic rulers — Alexander IV (r. 316–307 BC) or one of his successors, for example, Antiochus I (r. 281–261 BC) — appears to have planned to restored Esagil and Etemenanki since the brickwork from the upper stages of the ziggurat were removed and transferred to the northeast corner of the inner city of Babylon (now Homera), where a Greek theater was built on the brick fill. During the Sasanian Empire (224–651 AD), a fortress was constructed on the unbaked-brick core of the still-standing base of Etemenanki.

Archaeological Remains

By the start of the German excavations at Babylon led by Robert Koldewey in 1899, relatively little of the monumental ziggurat remained. This was in part due to the fact that in 1886 locals discovered the ruins of Etemenanki to be an excellent source for bricks. These brick miners removed the ziggurat's 15-m-wide, baked-brick outer mantel and left a deep, often-water-filled trench around what remained of the building's 60×60-m unbaked mudbrick core. In 1913, Koldewey and Friedrich Wetzel excavated the ruins of Marduk's temple-tower. Later, in 1962, Hansjörg Schmid investigated the ziggurat's core and the later building(s) constructed on top of it. Excavations on the surrounding, 400×400 m precinct were carried out by Wetzel in 1908–10, by Heinrich Lenzen and others in 1963–67 and 1972, and by Iraqi archaeologists in the 1980s.

Photos of the southwest corner (left) and southeast corner (right) of the remains of Etemenanki. Photographs from O. Pedersén, Babylon: The Great City, pp. 156–157 figs. 4.14 and 4.15.

In 1899, the unbaked mudbrick core, as well as some traces of the baked-brick mantel, remained. Although most of Etemenanki's outer casing had been removed by local brick miners in and before 1886, there were a few places where there were uninscribed baked bricks standing to a height of ca. 2 m; the sizes of the bricks more or less corresponded to those of bricks dating to the reign of Nabopolassar and the early years of Nebuchadnezzar II. On the south side of the ziggurat, excavators discovered traces of three staircases. The ruins of Sasanian and Islamic buildings — including a 90×90 m large fortification with rounded towers — sat atop the remnants of the ziggurat's core.

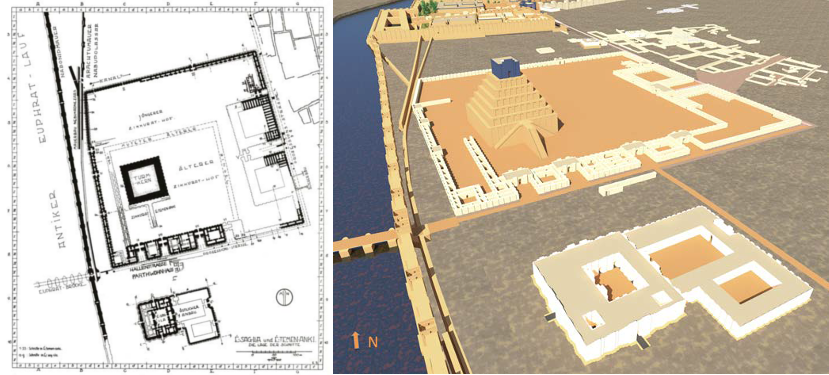

Plan of the Eridu district of East Babylon, including the ziggurat Etemenaki and the temple Esagil (left); digital reconstruction of Etemenaki and Esagil. Images from F. Wetzel, Das Hauptheiligtum des Marduk in Babylon, Esagila und Etemenanki, pl. 2; and O. Pedersén, Babylon: The Great City, p. 163 fig. 4.19.

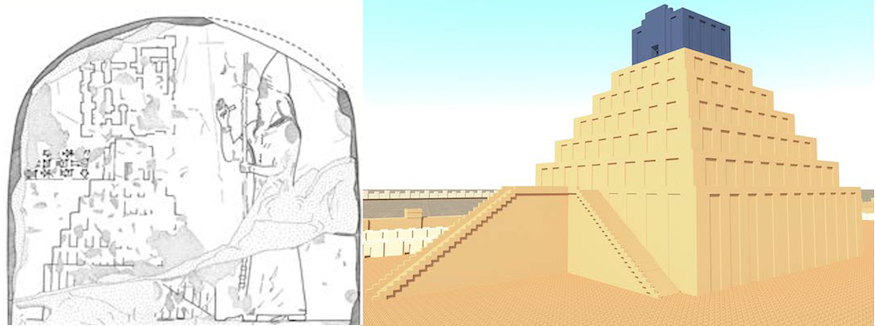

Based on information provided in the so-called "Esagil Tablet," a mathematical school tablet giving the measurements of Etemenanki, and the now-famous "Tower of Babel Stele," whose authenticity as a contemporary Neo-Babylonian monument is not entirely certain, together with details brought forth by the Austrian excavations of the better-preserved ziggurat Eurmeiminanki at Borsippa, Marduk's temple-tower is now generally thought to have had seven stages, six lower tiers with a blue-glazed-brick temple construction on top, although this cannot yet be proven with any degree of certainty. Etemenanki's base was 91.5 × 91.5 m (8400 m²) and its estimated height is 91.5 m (assuming, of course, that it was a seven-stage building as some scholars have suggested). The three staircases on the south side appear to have given access only to the first terrace. The upper terraces and the main temple on top of the ziggurat, however, seem to have been accessed via staircases built inside the brick structure. Eurmeiminanki, the temple-tower of the god Nabû at Borsippa, was similarly constructed. The number of terraces, the final height of the ziggurat in the time of Nebuchadnezzar, and the means by which the upper terraces were accessed are still matters of scholarly debate, especially now that a few scholars regard the "Tower of Babel Stele" as a modern fake, rather than as an authentic Nebuchadnezzar-period artefact.

Andrew George's hand-drawn facsimile of the upper portion of the obverse of the "Tower of Babel Stele" (MS 2063), which is housed in the Schøyen Collection in Oslo (left) and Olof Pedersén's digital reconstruction of Etemenanki based on the representation of the ziggurat on the "Tower of Babel Stele" and information provided about that building in the Esagil Tablet. Image created by Jamie Novotny from A.R. George, "A stele of Nebuchadnezzar II, in: A.R. George (ed.), Cuneiform Royal Inscriptions and Related Texts in the Schøyen collection, pl. 59; and O. Pedersén, Babylon: The Great City, p. 162 fig. 4.18.

Further Reading

- Allinger-Csollich, W. 1991. "Birs Nimrud I. Die Baukörper der Ziqqurat von Borsippa, ein Vorbericht," Baghdader Mitteilungen 22, pp. 383–499.

- Allinger-Csollich, W. 1998. "Birs Nimrud II: Tieftempel-Hochtempel: Vergleichende Studien Borsippa - Babylon," Baghdader Mitteilungen 29, pp. 95–330.

- Allinger-Csollich, W. 2013. "Gedanken über das Aussehen und die Funktion einer Ziqqurrat," in K. Kaniuth, A. Löhnert, J.L. Miller, A. Otto, M. Roaf, and W. Sallaberger (eds), Tempel im Alten Orient: 7. Internationales Colloquium der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 11.–13. Oktober 2009, München, Wiesbaden, pp. 1–18.

- George, A.R. 1992. Babylonian Topographical Texts (Orientalia Lovaniesia Analecta 40), Leuven, pp. 298–300 and 430–433.

- George, A.R. 1993. House Most High: The Temples of Ancient Mesopotamia (Mesopotamian Civilizations 5), Winona Lake, p. 149 no. 1088.

- George, A.R. 2005–6. "The tower of Babel: archaeology, history and cuneiform texts," Archiv für Orientforschung 51, pp. 75–95.

- George, A.R. 2010. "Xerxes and the Tower of Babel," in J. Curtis and St. J. Simpson (eds), The World of Achaemenid Persia: History, Art and Society in Iran and the Ancient Near East, London, pp. 471–480.

- George, A.R. 2011. "A stele of Nebuchadnezzar II, in: A.R. George (ed.), Cuneiform Royal Inscriptions and Related Texts in the Schøyen collection (Cornell University Studies in Assyriology and Sumerology 17), Bethesda, pp. 153–169 and Pls. LVIII–LXVII.

- Koldewey, R. 1990. Das wieder erstehende Babylon (5th revised edition, ed. by B. Hrouda), Munich, pp. 182–195.

- Pedersén, O. 2021. Babylon: The Great City, Münster, pp. 153–165.

- Schmid, H. 1990. "Rekonstruktionsversuche und Forschungsstand der Ziggurat von Babylon," in R. Koldewey, Das wieder erstehende Babylon, fifth edition (edited by B. Hrouda), Munich, pp. 303–342.

- Schmid, H. 1995. Der Tempelturm Etemenanki in Babylon (Baghdader Forschungen 17), Mainz.

- Wetzel, F. 1938. Das Hauptheiligtum des Marduk in Babylon, Esagila und Etemenanki (Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichung der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 59), Leipzig.

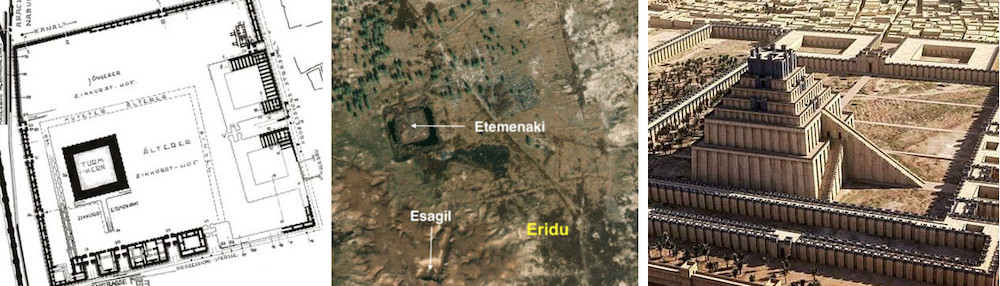

Banner image: plan of the Etemenanki precinct (left); satellite image of the Eridu district of East Babylon showing the locations of Etemenanki and Esagil (center); and digital reconstruction of Babylon's ziggurat as a seven-tiered temple-tower (right). Plan detail from F. Wetzel, Das Hauptheiligtum des Marduk in Babylon, Esagila und Etemenanki, pl. 2.

Jamie Novotny

Jamie Novotny, 'Etemenanki (ziggurat of Marduk at Babylon)', Babylonian Temples and Monumental Architecture online (BTMAo), The BTMAo Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, [http://oracc.org/btmao/Babylon/TemplesandZiggurat/Etemenanki/]