Ehulhul (temple of Sîn at Harran)

Ehulhul was one of the most important temples of the moon-god, at least in the first millennium BC, during the Neo-Assyrian (ca. 911–612 BC) and Neo-Babylonian (ca. 625–539 BC) Periods. Although the remains of this once-grand building have not yet been found, royal inscriptions of Ashurbanipal (r. 668–631 BC), Assyria's last great king, and Nabonidus (r. 555–539 BC), Babylon's last native ruler, provide a wealth of information about Ehulhul, including some of its interior decoration, and other temples at Harran, namely Egipar (the seat of the goddess Nikkal) and Emelamana (the temple of the god Nusku). Unlike many of the temples discussed on BTMAo, the long history of this temple of the god Sîn is presently known entirely from textual sources, rather than from both the textual and archaeological records.

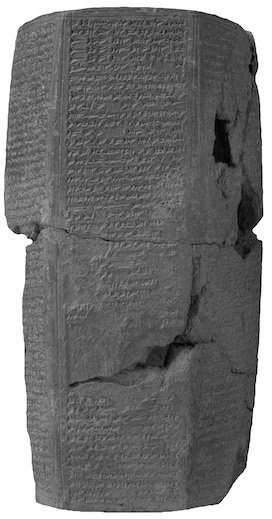

BM 121006+, a six-column clay prism that is inscribed with the so-called "Prism T[hompson] Inscription" of Ashurbanipal. Ehulhul's reconstruction is recorded in cols. ii–iii. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Names and Spellings

Harran's principal temple went by the Sumerian ceremonial name Ehulhul, which means "House Which Gives Joy." The name is principally attested in Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian royal inscriptions, most of which record its construction and interior decoration.

- Written Forms: é-ḫúl-ḫúl.

Known Builders

- Neo-Assyrian (ca. 911–612 BC)

- Shalmaneser III (r. 858–824 BC)

- Sargon II (r. 721–705 BC)

- Esarhaddon (r. 680–669 BC)

- Ashurbanipal (r. 668–ca. 631 BC)

- Neo-Babylonian (ca. 625–539 BC)

- Nabonidus (r. 555–539 BC)

Building History

Prior to the reign of the late Neo-Assyrian king Ashurbanipal, little is known about Harran's principal religious structures. A temple dedicated to the moon-god existed in Harran from at least the Old Babylonian Period (ca. 1900–1600 BC) onwards — from the reign of Narām-Sîn of Ešnunna (1808–1798 BC) or Zimrī-Līm of Mari (1774–1762 BC) — but beyond that, virtually nothing about Ehulhul and its building history is known before the seventh century BC. The Assyrian king Shalmaneser III, a son of the equally-renowned Ashurnasirpal II (883–859 BC), is the earliest ruler presently known from extant sources to have sponsored construction on Harran's temples. Because his sponsorship of Ehulhul's construction is recording only in later Assyrian and Babylonian royal inscriptions, no contemporary information or details about Shalmaneser's work on this temple of the moon-god are known.

It is clear from numerous sources, especially royal inscriptions, that Harran and its temples received special attention from Assyria's kings from the time of Sargon II, a son of Tiglath-pileser III (r. 744–727 BC) who was not originally destined for kingship, onwards. Since Harran's citizens aided Sargon in his bid for the throne against his older brother Shalmaneser V (r. 726–722 BC), the city was rewarded by abolishing the tax and corvée that had been previously imposed upon them and through large donations made to Ehulhul, some of which are recorded in an inscription written on a clay cylinder discovered at Nineveh. In that text, Sargon states that he used "seven and a half minas of shining silver for work (pertaining) to Ehulhul, the residence of the god Sîn, the one who resides in the city Harra[n]." The inscription, unfortunately, does not give any details about the item(s) that Sargon II had fashioned for that temple.

Esarhaddon, Sargon's grandson, together with his mother Naqi'a (who also went by the name Zakutu), also gave special attention to Ehulhul and its tutelary deities. From royal correspondence and royal inscriptions, this seventh-century-BC ruler and his mother (1) decorated Ehulhul; (2) donated metal(-plated) cult utensils; and (3) set up images of himself and his heir designates Ashurbanipal and Šamaš-šuma-ukīn, the future rulers of Assyria and Babylon respectfully, in the vicinity of the image of the moon-god. Clearly Esarhaddon had more important, long-term plans for Harran and Ehulhul — including making one of his younger sons, Aššur-etel-šamê-erṣetim-muballissu, a priest of Sîn — but he died (late in the year 669 BC) before he could carry them out. Fortunately, Ashurbanipal, his fourth eldest son and designated heir to the Assyrian throne, stepped up and realized Esarhaddon's ambitious building activities at Harran.

Of Ashurbanipal's numerous building activities in Assyria and Babylonia, rebuilding and expanding the Ehulhul temple complex took pride of place, as is clear from his many Akkadian inscriptions recording his work at Harran. Unlike Ashurbanipal's work in other cities — which mostly consisted of projects of Esarhaddon that he merely put the finishing touches — large-scale building at Harran was both initiated and completed under Ashurbanipal's authority. Royal inscriptions, in particular two texts that scholars now refer to as the "Large Egyptian Tablet (LET) Inscription " and the "Prism T Inscription," record details about every phase of Ashurbanipal's rebuilding of Ehulhul, from the removal of the temple's existing brick structure to the return of the divine statues to their daises during festive celebrations after Ehulhul brick superstructure had been completed and roofed (with beams of cedar) and its interior (especially its holiest rooms) had been lavishly decorated. The relevant passage in the "Prism T Inscription" reads:

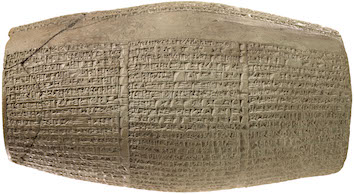

VA 02536, a three-column clay cylinder that is inscribed with the so-called "Ehulhul Cylinder Inscription" of Nabonidus. Ehulhul's reconstruction is recorded in detail in cols. i–ii. © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Vorderasiatisches Museum. Photo: Olaf M. Teßmer.

Not only did Ashurbanipal rebuild the entire structure of Ehulhul — which according to another inscription was thirty courses of bricks high (ca. 3.3–3.6 m) — he also greatly expanded the temple complex. This appears to have been in connection with the construction of an entirely new temple for the god Nusku, an important member of the moon-god's divine entourage. According to the "Large Egyptian Tablet Inscription," that new religious structure was constructed on a 130-brick-course-high terrace, in a plot of land measuring ca. 175×32.5 m. Ashurbanipal might have constructed Nusku's new temple, which went by the Sumerian ceremonial name Emelamana (which means "House of the Radiance of Heaven"), as a twin or mirror image of Ehulhul. Because neither the ruins of Ehulhul nor Emelamana have yet been discovered at Harran, this suggestion cannot be confirmed. Moreover, it is unknown if Emelamana was physically attached to Ehulhul or if it was a separate, fully-detached building; this is not clear from extant sources.

The interior rooms, at least the ante-cellas (Akkadian bīt papāhi) and cellas (Akkadian atmanu), of both Ehulhul and Emelamana were lavishly decorated and had metal(-plated) and inscribed apotropaic figures placed in important gateways; vast amounts of metal acquired during Ashurbanipal's second Egyptian campaign (664 BC) were the principal source of the silver alloy used to ornament Harran's temples. Sîn's ante-cella and cella had at least three pairs of protective figures stationed in them: wild bulls (Akkadian rīmu), long-haired heroes (lahmu), and lion-headed eagles (anzû). In Nusku's new ante-cella, Ashurbanipal had at least one pair of lion-headed eagles fashioned as gateway guardians. Numerous other metal and metal-plated objects were created for the divine residents of the expanded Ehulhul temple complex, including a pair of gold-plated carrying poles for Sîn's consort Nikkal and a reddish-gold-plated archway or awning for Emelamana.

The grand and radiantly-decorated temple complex built by Ashurbanipal did not survive long after that king's death (ca. 631 BC). It was thoroughly destroyed twenty years later, in 610 BC, during the reign of his grandson Aššur-uballiṭ (r. 611–609 BC), the last ruler of Assyria. Harran and its temples were plundered and devastated when the armies of Nabopolassar (625–605 BC), the founder of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, and his Median ally Cyaxares conquered Harran. Ehulhul was in ruins until Nabonidus ascended the throne of Babylon and set his sights on returning that important temple back to its former glory.

Two inscribed Neo-Babylonian steles written in the name of Nabonidus' mother Adad-guppi. Image credit: Ronnie Jones III, "Tablets with King Nabonidus Inscriptions, Harran," World History Encyclopedia. © Ronnie Jones III.

As with Ashurbanipal, there are numerous royal inscriptions of Nabonidus that include information about that Neo-Babylonian king's rebuilding of Sîn's temple at Harran. That major undertaking might have started after his return to Babylon (ca. 543 BC), after his ten-year sojourn in Arabia, at which time he resumed direct control over Babylonia and its territorial holdings, including the area around Harran. In a text now commonly referred to as the "Ehulhul Cylinder Inscription", Nabonidus claims to have rebuilt this temple of the moon-god directly on top of the foundations of Ashurbanipal. As one expects from an account of construction in a Mesopotamian royal inscription, it stated that the king had the brick superstructure completed in its entirety, had its interior decorated lavishly, and had newly-refurbished statues of its divine occupants (Sîn, Ningal/Nikkal, Nusku, and Sadarnunna) returned to their proper places in their home town; they had been in exile in Babylon since Harran's destruction in 610 BC. The description of Nabonidus' works in the "Ehulhul Cylinder Inscription" reads as follows:

In memory of his mother Adad-guppi (Aramaic Hadad-ḥappī), a woman who lived to the old age of 101 (although her stele inscription states that she was 104), Nabonidus had steles erected in Ehulhul in order to honor her life-long devotion to the moon-god, the patron deity of Harran, her (assumed) birth city. Although Nabonidus' inscriptions always state that the work on the temple had been completed, it is unknown if construction on Sîn's temple at Harran had actually been finished when the Persian king Cyrus II captured Babylon and Nabonidus in 539 BC.

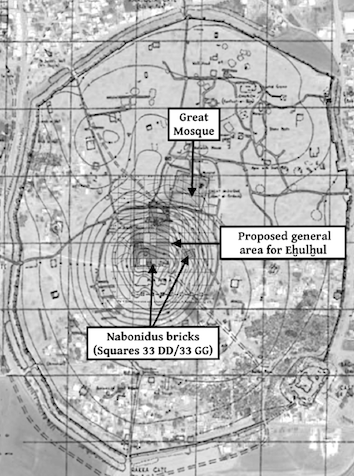

Satellite image of Harran overlaid with a general plan of the city and the excavated areas of the city. Image created by Jamie Novotny.

Archaeological Remains

British and Turkish excavations of the ruins of Harran in the 1950s, 1980s, and 1990s have not unearthed a single inscribed Assyrian object, nor have these scientific investigations found the remains of Ehulhul, apart from numerous bricks and half-bricks of Nabonidus. It is possible that the temple complex was located near the edge of the city's citadel, possibly in the northeastern quadrant. Given the (oral and) written tradition that the Paradise Mosque was constructed on top of Ehulhul, and the fact that numerous stamped bricks of Nabonidus were found in trenches 35 DD and 36 GG and that steles of that Neo-Babylonian king and his mother Adad-guppi were reused in the structure of the mosque, it is not impossible that Sîn's temple was located in the northeastern part of the mound (höyük). This proposed location, however, is yet to be confirmed from the archaeological record.

Further Reading

- Campbell Thompson, R. 1940. "A Selection from the Cuneiform Historical Texts from Nineveh (1927–32)," Iraq 7, pp. 85–131.

- George, A.R. 1993. House Most High. The Temples of Ancient Mesopotamia (Mesopotamian Civilizations 5), Winona Lake, p. 99 no. 470.

- Groß, M. 2014, "Ḫarrān als kulturelles Zentrum in der altorientalischen Geschichte und sein Weiterleben," in L. Müller-Funk, S. Procházka, G. Selz, and A. Telič (eds), Kulturelle Schnittstelle. Mesopotamien, Anatolien, Kurdistan. Geschichte. Sprachen, Vienna, pp. 139–154.

- Jeffers, J. and Novotny, J. 2023. The Royal Inscriptions of Ashurbanipal (668–631 BC), Aššur-etel-ilāni (630–627 BC) and Sîn-šarra-iškun (626–612 BC), Kings of Assyria, Part 2 (Royal Inscriptions of the Neo-Assyrian Period 5/2), University Park, pp. 23–25.

- Hätinen, A. 2021. The Moon God Sîn in Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian Times (dubsar 20), Münster, especially pp. 384–415.

- Novotny, J. 2003. Eḫulḫul, Egipar, Emelamana, and Sîn's Akītu-House: A Study of Assyrian Building Activities at Ḫarrān, University of Toronto, unpublished PhD dissertation.

- Novotny, J. 2020. "Royal Assyrian building activities in the northwestern provincial center of Ḫarrān," in S. Hasegawa and K. Radner (eds.), The Reach of the Assyrian and Babylonian Empires: Case studies in Eastern and Western Peripheries (Studia Chaburensia 8), Wiesbaden, pp. 73–94.

- Weiershäuser, F. and Novotny, J. 2020. The Royal Inscriptions of Amēl-Marduk (561–560 BC), Neriglissar (559–556 BC), and Nabonidus (555–539 BC), Kings of Babylon (Royal Inscriptions of the Neo-Babylonian Empire 2), University Park, pp. 10–12.

Jamie Novotny & Joshua Meynell

Jamie Novotny & Joshua Meynell, 'Ehulhul (temple of Sîn at Harran)', Babylonian Temples and Monumental Architecture online (BTMAo), The BTMAo Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, [http://oracc.org/btmao/Harran/Ehulhul/]