Holy Rooms and Gates of Etemenanki

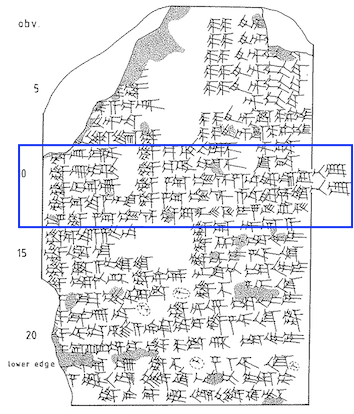

A.R. George's hand-drawn facsimile of the obverse of BM 35046, a clay tablet inscribed with a text called the "Gate List of Esagil A." Etemenanki's gates are listed in obverse lines 9–12. Reproduced from A.R. George, Babylonian Topographical Texts, pl. 21.

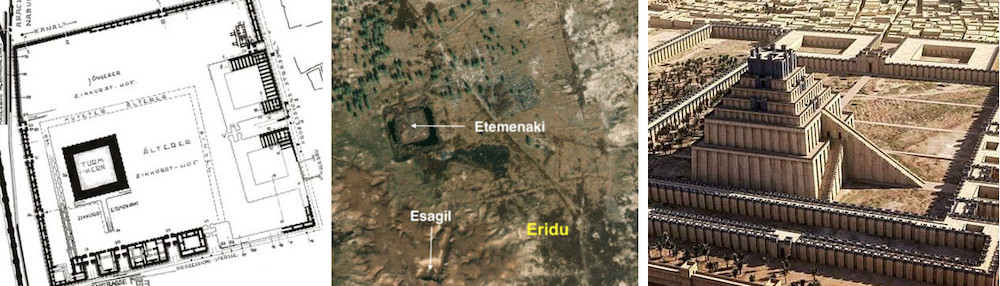

Some information about Etemenanki's gates and the blue-glazed temple on top of it is provided in two lists of Esagil's gates, in the so-called "Esagil Tablet" (a mathematical school tablet giving the measurements of Etemenanki), and in two royal inscriptions of the Neo-Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 604–562 BC) written on rock faces in Lebanon. Moreover, the now-famous "Tower of Babel Stele," whose authenticity as a contemporary Neo-Babylonian monument is not entirely certain, purportedly depicts the ground plan of the ziggurat temple.

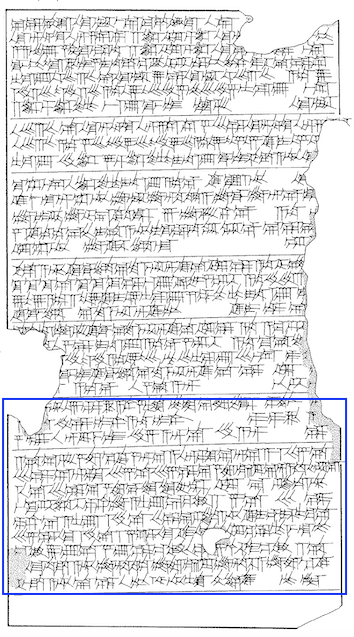

The blue-glazed temple that was constructed atop the massive and towering ziggurat, at least according to the "Esagil Tablet," was a small temple that comprised four separate parts centered around a roofed courtyard. The eastern wing, which was accessed by the "Gate of the Rising Sun" (Akkadian bāb ṣīt šamši), housed the cellas of the deities Marduk, Nabû, and Tašmētu. The cellas of the gods Ea and Nusku were located in the northern part of the temple, which was entered from the courtyard via the "Northern Gate" (Akkadian bāb iltāni). The southern wing, whose main entrance was the "Southern Gate" (Akkadian bāb šūti), was the location of the chapel shared by the gods Anu and Enlil. From the central courtyard, the ziggurart's staircase was reached via the "Gate of the Setting Sun" (Akkadian bāb ereb šamši) and the western wing of the temple.

Etemenanki had at least four additional gates: Kanunabzu, Kanunhegal, Kaunir, and Kaetemenanki. The first two are described as "the gate of the upper bronze door" and "the gate of the lower bronze door," while the last two are referred to as "the gate of the ziggurat temple that opens to the south" and "the gate of the ziggurat temple that opens to the west." Kaunir and Kaetemenanki appear to be the external gates of the temple that sat atop Etemenanki, while Kanunabzu and Kanunhegal were likely located close to the ziggurat temple, perhaps on the (final) staircase leading up to it. The second ruler of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, Nebuchadnezzar II, claims to have rebuilt all four of these gates.

A.R. George's hand-drawn facsimile of the obverse of AO 6555, the so-called "Esagil Tablet." The ziggurat temple is described in lines 25–36. Reproduced from A.R. George, Babylonian Topographical Texts, pl. 24.

Names and Spellings

The Sumerian ceremonial names of four gates of Etemenanki are known. These are Kanunabzu, Kanunhegal, Kaunir, and Kaetemenanki. Respectively, these names mean "Gate of the Prince of the Apsû," "Gate of the Prince of Abundance," "Gate of the Ziggurat," and "Gate of Etemenanki."

- Written Forms: ka₂-e₂-te-men-an-ki; ka₂-nun-abzu; ka₂-nun-he₂-gal₂; ka₂-u₆-nir.

Known Builders

- Neo-Babylonian (ca. 625–539 BC)

- Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 604–562 BC)

Building History

Nebuchadnezzar II claims that he constructed four of Etemenanki's gates after his workmen had finished constructing the ziggurat's massive brick structure, which his father Nabopolassar (r. 625–605 BC), the founder of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, had started. The so-called "Wadi Brisa A[rchaic] Inscription," an Akkadian inscription written on a rock face in modern-day Lebanon, records the following:

Archaeological Remains

Given that little of Etemenanki remained by the start of the German excavations at Babylon led by Robert Koldewey in 1899, it is no longer possible to identify Kanunabzu, Kanunhegal, Kaunir, and Kaetemenanki in the archaeological record. The same is true of the ziggurat temple that was built on top of it.

Further Reading

- George, A.R. 1992. Babylonian Topographical Texts (Orientalia Lovaniesia Analecta 40), Leuven, pp. 298–300 and 89–90.

Banner image: photograph of the remains of Ezida and Eurmeiminanki taken ca. 2002 (left); woodcut from "Pleasant Hours: A Monthly Journal of Home Reading and Sunday Teaching; Volume III" published by the Church of England's National Society's Depository, London, in 1863 (center); areal photograph of the ruins of Ezida and Eurmeiminanki taken in 1928 (right). Images from Getty Images.

Jamie Novotny

Jamie Novotny, 'Holy Rooms and Gates of Etemenanki', Babylonian Temples and Monumental Architecture online (BTMAo), The BTMAo Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, [http://oracc.org/btmao/Babylon/TemplesandZiggurat/Etemenanki/RoomsandGates/]