The royal family: queen, crown prince, eunuchs and others

The family tree of the Assyrian royal family, 700-650 BC. View large image.

Apart from the king, the most prominent and visible members of the Assyrian royal family were the queen (literally "woman of the palace") and the crown prince TT (literally "son of the king"). By the 7th century BC, their political and administrative responsibilities were considerable, and both also commanded their own standing army. The connections between the king and queen, and between the king and crown prince, are self-evident but there was also a close link between queen and crown prince. For while the king had several consorts, the queen was normally the mother of the son who had been chosen as crown prince. Certain queens very actively promoted their sons' interests.

The queen and the king's mother

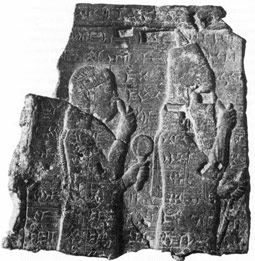

Naqi'a, the king's mother (identified by an inscription), with her son, king Esarhaddon; bronze relief in the Louvre (AO 20185); photo from I. Seibert, Die Frau im Alten Orient (Leipzig, 1973) pl. 62. View large image.

Thanks to the surviving court correspondence, the Assyrian royal family is best known to us during the reign of Esarhaddon (681—669 BC). At that time, several female members of the royal family held positions of great influence. The power of Esarhaddon's wife, queen Ešarra-hammat, was much noticed even outside palace circles; her death in the year 673 is mentioned prominently in two contemporary Babylonian chronicles. The widowed king had a mausoleum in the city of Assur erected, and special rites for his dead wife's funerary care were arranged. The vacant position of the Assyrian queen was then filled by Esarhaddon's mother Naqi'a PGP , who had already played a key role in her son's appointment as crown prince and in his eventual taking of power.

Soon afterwards, when Esarhaddon's son Assurbanipal was formally appointed crown prince of Assyria in 672, his dead mother Ešarra-hammat was thought to have risen from her grave to secure her favourite son's claim: according to a contemporary letter, her ghost TT appeared to the new crown prince in a dream, blessing him and pronouncing him and his heirs the rightful rulers of Assyria (SAA 10: 188). His grandmother Naqi'a, too, sought to cement Assurbanipal's succession to royal power. She made all those who could at one point have entertained hopes to succeed Esarhaddon as king of Assyria, especially Assurbanipal's elder brothers, take an oath to ensure their loyalty to Assurbanipal. Most importantly, Šamaš-šumu-ukin PGP , Assurbanipal's older brother (see SAA 10: 185), was made to accept his brother's more prominent position while he himself was appointed crown prince of Babylon PGP – a prestigious office, for sure, but clearly only second prize when compared to being made heir to the Assyrian empire.

A powerful princess

Esarhaddon's eldest daughter, Šerua-eṭirat PGP , also occupied a prominent position at the royal court. Some of her surviving letters illustrate her self-confidence as royal princess and representative of her family. One such letter is addressed to her sister-in-law, Assurbanipal's young wife Libbali-šarrat, the future queen of Assyria, whom she scolds for her poor school performance:

Why don't you write your paper (literally, "tablet") and do your homework? For if you don't, people will say: "Is this really the sister of the royal princess Šerua-eṭirat?" You are, after all, married to the crown prince of Assyria. (SAA 16: 28)

We do not know whether Šerua-eṭirat ever married, but it is certain that such a union would have been engineered to strengthen the Assyrian royal family's ties with another royal house. From a divinatory query to the sungod, we know that Esarhaddon considered offering one of his daughters in marriage to Bartatua PGP , king of the Scythians PGP (SAA: 4 20), as part of an alliance treaty. The sources do not reveal whether this marriage ever took place and, if so, who was chosen as the bride. It is extremely unlikely, however, that Šerua-eṭirat ever left for the far-away regions controlled by the Scythians, as her influence in Assyria continued, even after her father's death in 669. Most significantly, in 652 she tried to mediate in the escalating conflict between her brothers Assurbanipal and Šamaš-šumu-ukin, then king of Babylon. While she couldn't prevent the four long years of war for control over Babylonia, her peace initiative is without parallel for any Near Eastern woman of that era.

Esarhaddon's many sons

So far, we have encountered three of Esarhaddon's children: Assurbanipal, the crown prince and later king of Assyria; his elder brother Šamaš-šumu-ukin, the crown prince and later king of Babylon; and the princess Šerua-eṭirat. Many more sons and daughters of Esarhaddon are attested, yet whether they too were Ešarra-hammat's children is unknown. One son, Sin-nadin-apli PGP , was at one point before 677 BC considered a good choice for Assyrian crown prince (SAA 4: 149) and even seems to have ascended to that position. It is not known what happened to him then but he was most probably dead by 672 when Assurbanipal was appointed crown prince. Two other sons, Aššur-mukin-paleya PGP and Aššur-etel-šame-erṣeti-muballissu PGP , were appointed to prestigious offices, to match their illustrious names ("Aššur is the one who established my [i.e., the father's] reign" and "Aššur, the prince of heaven and earth, is the one who keeps him alive"), at the temple of Marduk PGP of Babylon PGP and the moongod of Harran PGP after their brother Assurbanipal came to the Assyrian throne. These and other princes are mentioned in Esarhaddon's correspondence with his scholarly advisors. While some letters deal with suitable dates for encounters between the father and his children, many others concerning their health seem to imply that Esarhaddon passed on his frail constitution to his offspring. The names of two sons in particular suggest they were in poor health from birth onwards: The name Šamaš-metu-uballiṭ "Šamaš resurrected the dead one" points to the fact that the baby survived his birth against all odds, while the name Aššur-taqiša-libluṭ "O Aššur, you have granted (a son); may he live!" is essentially a prayer for the life of a sickly newborn boy.

The royal eunuchs

The Assyrian king with a royal eunuch, performing a libation sacrifice over the body of a slain lion; detail from the stone decoration of Assurnasirpal II's Northwest Palace at Nimrud, c.865-860 BC (room B, panel 19, lower register; BM ANE 124535). Photo by Eleanor Robson. View large image.

No discussion of the Assyrian royal family would be complete without the mention of the royal eunuchs TT , who could be described almost as the adopted sons of the king. A eunuch, literally "One of the head", was a castrated man who could serve the king and his family in various functions, from commander-of-arms and provincial governor to bodyguard and manservant. It is unclear today what qualities or qualifications were looked for in a boy, or who made the fundamental decision to turn him into a eunuch. Neither is anything known about their original family backgrounds—but there is no reason to think that being made a eunuch was considered a terrible fate and we certainly shouldn't assume that future eunuchs were necessarily forced into this life. For being a royal eunuch guaranteed high social status and a place in the royal household for life and, crucially, beyond. According to Assyrian thought, a person's well-being in the afterlife was inseparable from and dependent on the regular funerary offerings received after death, usually from one's descendants. But along with his manhood, a eunuch sacrificed the chance to have children. The royal family's promise to provide for him in the afterlife was therefore essential. The eunuch's inability to reproduce was in turn one of his attractions for the royal clan, who did not have to fear that familial ties might dilute his loyalty to the king. And despite being so very close to royal power, a eunuch could never hope to become king himself. As kingship required a man to be perfect in all respects, a eunuch, with his mutilated body, was naturally excluded from that office. It is an indication of the increasingly hazardous state of the Assyrian empire in the late 7th century BC that even this iron rule lost its rigidity, and one royal eunuch, Sin-šumu-lešir, could openly if ultimately unsuccessfully claim royal power.

Further reading

- Melville, 'Neo-Assyrian royal women', 2004

- Radner, Baker, et al., Prosopography, 1998- (letters A-S so far)

Content last modified: 07 Mar 2025.

Karen Radner

Karen Radner, 'The royal family: queen, crown prince, eunuchs and others', Knowledge and Power, Higher Education Academy, 2025 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/saao/knpp/Essentials/Royalfamily/]