Discovery and decipherment, from winged bulls to websites

When the Medes and Babylonians destroyed Nineveh PGP in 612 BC the Assyrian empire collapsed. Its palaces were abandoned and fell into ruins, burying tools and ornaments, archives and libraries under the rubble for over 2500 years. It was not until the 1840s that the Assyrian capital was rediscovered through excavation. More than 150 years after the decipherment of cuneiform writing, historians and archaeologists are still finding new ways to understand the intellectual, social, and political history of ancient Assyria.

Assyria imagined

Eugene Delacroix's romantic vision of the death of the legendarily decadent Assyrian king Sardanapalus (1827), as recounted in Greek myth and retold in Byron's play Sardanapalus (1822). © Musée du Louvre. View image on the Louvre's website [https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010065757].

Although all knowledge of cuneiform script had died out by the first centuries CE, images of Assyria lived on in classical and biblical traditions. The Old Testament naturally depicted Nineveh as the oppressor of Israel and Judah (e.g., in Kings II; Jonah), while Greek stories told of mythical despots such as Sardanapalus, who "surpassed all his predecessors in luxury and sloth" (Diodorus Siculus). In the early nineteenth century European artists and writers captured romantic visions of Oriental decadence in works such as Lord Byron's poem The Destruction of Sennacherib (1815) and Eugene Delacroix's oil painting Mort de Sardanapale (Death of Sardanapalus) (1827).

Assyria refound

Victor Place pioneered the use of photography in archaeology when he took over excavations at Khorsabad (ancient Dur-Šarruken) in the 1850s. Here a monumental palace gateway, flanked by protective winged bulls, comes to light in 1853. Photograph by Gabriel Tranchard (E. Fontan (ed.), De Khorsabad a Paris: La découverte des Assyriens, Paris 1994, p. 142 fig. 7.). View large image

Delacroix and Byron furnished their works with convincing historical detail solely through their imaginative powers, but within a generation the great museums of France and Britain were awash with genuinely ancient Assyrian artefacts. The Louvre held its first exhibition of objects from Sargon's PGP palace at Dur-Šarruken PGP in 1847. In 1852 a huge winged lion from Nineveh graced the Illustrated London News as it was carried up the steps of the British Museum. The general public flocked to gaze on the mute witnesses of a lost world, at once familiar through Bible readings and yet strangely alien in style. Indeed, in these years after Charles Lyell's hotly debated book, The Principles of Geology (1830), which directly challenged the Biblical account of the divine creation of the world, many Christians, scientists among them, grasped at the Assyrian discoveries as the first independent evidence for the truth of the Old Testament.

But while Lyell and his geologist colleagues based their publications on careful, systematic observation and analysis of the natural world, the rediscovery of Assyria belonged to no existing scientific discipline. Several decades before the advent of stratigraphic archaeology and associated recording techniques, travellers and adventurers in the far reaches of the Ottoman empire were discovering and excavating the great Assyrian ruins more by luck than judgement and with far more energy than skill. In the early 1840s Paul Emile Botta, the under-employed French consul in Mosul and a former botanist, began exploring the massive mounds around the northern Tigris PGP , which were rumoured to cover the ruins of ancient Assyrian cities. He had little success at Nineveh itself, but most spectacularly unearthed monumental sculpture, low-relief wall panels, and inscribed bricks from the enormous palace at nearby Dur-Šarruken. Once the French government learned of his finds, they began to finance the work in exchange for monuments for the Louvre. It was thought that ancient objects, like botanical specimens, should be cleaned and classified and displayed in glass cases for the edification of the museum-going public. But the French authorities also sent an artist, Eugene Flandin, to help document the discoveries, thereby preserving some information about the original contexts of the finds. By the 1850s Botta's successor, Victor Place, was using photography to record the digs. When a massive shipment of antiquities was sunk on the Tigris en route to Paris, these secondary sources of evidence gained even greater importance than before.

A young English dilettante named Austen Henry Layard, dallying in the Middle East to avoid a career in law, befriended Botta in 1842. Three years later, with permits from Istanbul and the financial backing of the British Ambassador, Sir Stratford Canning, he began excavations at Nimrud, ancient Kalhu PGP . Layard correctly intuited the location of major palace buildings on the site, tunnelling through the earth to discover bas-reliefs and a pair of enormous stone winged bulls which had formed a monumental gateway. These finds were sufficient to attract the attention of the British Museum, which funded Layard's diggings at Nimrud, and later Nineveh and Assur PGP for a further three years. Layard returned to England in 1848 to prepare an exhibition and publication of his Assyrian discoveries but, overwhelmed by the resulting publicity, headed back to Assyria to continue the hunt for portable antiquities. Over the following three years Layard based himself at Nineveh, uncovering Sennacherib's "New Palace" PGP and Assurbanipal's Library but also made preliminary explorations of surrounding mounds. These met with varying success, as neither he nor his French counterparts had yet suspected the existence of unbaked mud-brick buildings in the ruin mounds, never mind developed the means to identify and excavated them effectively. Nevertheless, by the end of this second expedition, in April 1851, Layard had amassed a phenomenal 120 cases of antiquities for the British Museum.

Assyria deciphered

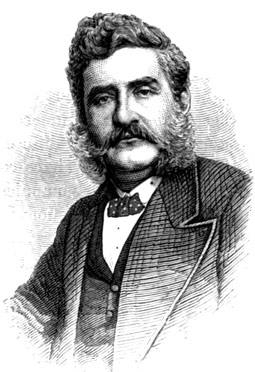

Hormuzd Rassam (1826-1910), a Christian from Mosul, was the first locally-born archaeologist of Assyria. In 1852 he succeeded Layard as the British Museum's director of excavations at Nineveh and Kalhu and was later elected a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society. Engraving from Newman, Thrones and palaces of Babylon and Nineveh, New York 1876, p. 366.

Meanwhile, the race was on to decipher the strange, wedge-shaped writing that not only decorated the stone sculpture that Botta and Layard had unearthed but also covered the surface of the fired clay objects that soon came to be known as cuneiform tablets. The cuneiform (wedge-shaped) alphabet of the Achaemenid Persians (6th century BC) had already been deciphered in the 1830s. In 1835, Henry Creswicke Rawlinson, a British diplomat acting as military advisor to the Persian empire, had made a papier mâché cast of an enormous trilingual inscription, carved high up in a mountain pass at a place called Bisutun near Persia's border with Ottoman Iraq. It soon became apparent that the Achaemenid text recorded events in the first regnal year of Darius (r. 522–486 BC) which closely paralleled the account in Herodotus' Histories, 3.61-79. But where the Achaemenid alphabet comprised just 42 different cuneiform signs, the other versions of the account, and the writing on the Assyrian objects that started to come to light in the mid-1840s, contained around ten times as many different components.

Prompt publication of the cuneiform inscriptions brought an international dimension to decipherment of Assyrian. The Swede Isidore Löwenstern recognised that Assyrian was a member of the Semitic language family, like Hebrew and Arabic; the Irishman Edward Hincks realised that Assyrian writing was mostly syllabic; and Botta showed that logograms could replace syllabic spellings in otherwise duplicate passages. But it was difficult for the public to believe that the apparently meaningless scratches could really be read. So in 1857 Henry Fox Talbot persuaded the Royal Asiatic Society in London to hold a competition in which he, Rawlinson, Hincks, and the French scholar Jules Oppert were each given a copy of an Assyrian royal inscription to translate. Their resulting translations were virtually identical, and so the Society declared that decipherment of Mesopotamian cuneiform was essentially complete.

In the following decades, increasing emphasis was placed on the discovery and decipherment of textual evidence, as more and more of the Old Testament world was brought to life through Assyrian words. Strong religious sentiments fed the British general public's appetite for all things Assyrian, while the emerging picture of the Assyrian empire presented an ancient mirror to Britain's own imperial self-image. It has even been suggested that the high Victorian fashion for full beards was partially influenced by the carefully coiffed facial hair of Assyrian kings. In 1872 a curator at the British Museum, one George Smith, discovered that a tablet from Assurbanipal's Library contained a version of the Biblical Flood TT story (as recounted by a Noah-like figure to the hero Gilgamesh PGP ). The public interest in this startling discovery was so great the the Daily Telegraph sponsored Smith to travel to Assyria for the very first time, in order to hunt for more pieces of the story. Extraordinarily, he succeeded within a week. However, Smith's promising career was cut short by a fatal bout of dystentery during a further tablet-collecting mission to Assyria just a few years later.

Assyriology today

In the Middle East and all over the world, there are modern communities who trace their ancestry back to ancient Assyria. On 1 April 2002 the Assyrians of Hasake in northern Syria marked the 6752nd Assyrian New Year (akitu) with processions and weddings. Photo by Bassem Tellawi. View large image. View more photos. [https://www.suwar-magazine.org/en/albums/61_festivals-of-the-syriacs-and-chaldo-assyrians-on-the-assyrian-babylonian-new-year-akitu-karchiran-village-terba-sebi-countryside-northeastern-syria]

The impressive achievements of those mid-Victorian explorers and philologists are not the end of the story. In the early 20th century German scholars such as Robert Koldewey at Babylon and Walter Andrae at Assur transformed the excavation process from old-style antiquaries' treasure hunts into the carefully recorded stratigraphic archaeology of today. Little excavation in the Assyrian heartland has been possible since the Gulf War of 1991, but that has encouraged archaeologists to explore Assyria's provinces and vassals in Syria, Turkey, and the Levant. For the most part the cities of ancient Assyria have avoided the worst postwar depradations suffered by the archaeological sites of southern Iraq, though Mosul Museum was looted in 2003. In the British Museum Assyriologists still pore over the tablets of Assurbanipal's Library, joining fragments, identifying their contents, and painstakingly piecing together critical editions of ancient letters, administrative records, and scholarly works. But now there is a substantial academic literature to support them: dictionaries, sign lists, grammar books and reference works, and an increasing number of online reference tools. British Museum staff are working with Iraqi colleagues to share information, increasing the world-wide accessibility and public understanding of Assyria for the next generation.

Further reading

- Bohrer, Orientalism and visual culture, 2003

- Damrosch, The buried book, 2007

- Holloway, 'Biblical Assyria', 2001

- Larsen, Conquest of Assyria, 1996

- Dean, 'Smith', 2004

- Ferrier and Dalley, 'Rawlinson', 2004

- Parry, 'Layard', 2004

- Wright, 'Rassam', 2004

Content last modified: 07 Mar 2025.

Eleanor Robson

Eleanor Robson, 'Discovery and decipherment, from winged bulls to websites', Knowledge and Power, Higher Education Academy, 2025 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/saao/knpp/Essentials/Discoverydecipherment/]