Assurbanipal, king of Assyria (669–c.630)

Assurbanipal, the last "great" king of Assyria, was a younger son of king Esarhaddon and his queen Ešarra-hamat and the grandson of king Sennacherib PGP and the formidable Naqi'a PGP . Married to queen Libbali-šarrat, he ruled from 669 until at least 630 BC; the last years of his reign are so poorly documented that it is difficult to establish when precisely he was succeeded by his son Aššur-etel-ilani.

Egypt regains its independence

Assurbanipal and Libbali-šarrat celebrating the defeat of the Elamites in 645 BC. © The British Museum. View large image on the British Museum's website.

Assurbanipal (Ashurbanipal) was appointed crown prince TT of Assyria in 672 BC and ascended to the throne uncontested in 669 after Esarhaddon had died en route to Egypt PGP , in order to end an anti-Assyrian rebellion supported by the Nubian king Taharqa PGP and his troops. Assurbanipal continued his father's military campaign to Egypt and the Nubians were forced out, with Necho PGP prince of Sais being installed as the new pharaoh of a newly united Egypt under Assyria's supremacy. Yet in 664 Taharqa's nephew and successor Tantamani again made a bid for Nubian control over Egypt but the swiftly dispatched Assyrian army succeeded in driving out the Nubians, this time for good. Assurbanipal had Necho, fallen in battle, replaced with his son Psammetikh. The new pharaoh had previously been living in Nineveh PGP as a royal hostage but subsequently managed to gain complete independence from Assyria while keeping relations relatively friendly; he is considered the founder of the 26th dynasty, which ruled Egypt until the Persian conquest.

Two royal brothers fighting for Babylon

In 672, when Assurbanipal was chosen as Assyrian crown prince, his older brother Šamaš-šumu-ukin PGP was simultaneously appointed to be crown prince of Babylon PGP . This meant that upon the death of Esarhaddon, who had jointly ruled Assyria and Babylonia, the realm was split into two: Assyria was Assurbanipal's kingdom while Šamaš-šumu-ukin was to be king of an independent Babylonia. The reality, however, was less like the dual monarchy that Esarhaddon may have had in mind; Assurbanipal considered his brother an Assyrian vassal and reserved a prominent role in Babylonian religious und public life for himself. The situation became increasingly volatile, especially when the friendly relations between Assyria and Elam PGP , which Esarhaddon had initiated, disintegrated. Pro-Elamite, and anti-Assyrian, influence in Babylonia began to grow. The Assyrian army finally invaded Elam in 653 and according to the Assyrian point of view, Elam was from that moment on a vassal state. In practice, the Assyrian control over Elam was brittle, and this became obvious once Šamaš-šumu-ukin, with the support of Elam and other enemies of Assyria, renounced Assyrian hegemony, or more precisely his brother Assurbanipal's. In 652, the king of Babylon claimed pre-eminence over Assyria, declaring Assurbanipal to be nothing but the Babylonian governor in Nineveh, and this led to open war. The Assyrian army was dispatched to Babylonia and, after four years of brutal war and at great cost to the Babylonian people, finally gained control over the country in 648 BC. Šamaš-šumu-ukin is thought to have committed suicide when Babylon was taken. Assurbanipal refrained from proclaiming himself king of Babylon but instead installed as ruler one Kandalanu, whose origins and personality are so shadowy that the fairly unlikely hypothesis that he was really an alter ego of Assurbanipal's still finds occasional support among modern historians.

Assurbanipal - crafty survivor or paranoid coward?

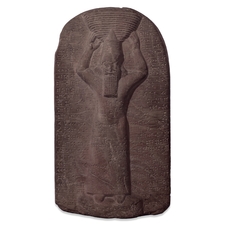

After the defeat of Šamaš-šumu-ukin, Assurbanipal portrayed himself as the rebuilder and restorer of Babylon. On this stele he carries a basket of earth for the ritual manufacture of the first brick to be laid for repairs to the god Ea's temple in Babylon. © The British Museum. View large image on the British Museum's website.

With the costly war in Babylonia and Egypt and Elam slipping out of Assyria's control, Assurbanipal's reign cannot easily be deemed successful, and yet he managed to stay on the throne for more than 40 years - much longer than his predecessors. Moreover, he seems to have avoided becoming the victim of a conspiracy like those that had haunted the reigns of his father and grandfather. It is clear that Assurbanipal, unlike previous Assyrian kings, rarely saw military action. Instead of leading the troops into battle the king did not even accompany the army on campaign - this may have considerably prolonged his life span but must be considered a radical departure from the expected behaviour of Assyria's ruler. While the Assyrian army was invading Elam Assurbanipal was back in Nineveh praying for success; but when the army returned victorious he took the leading role in the re-enactments of the battles and the triumphant processions that included the parading and public torturing of the most prominent captives. Such performances aside, he seems to have led an isolated existence, protected and screened off from his subjects by his body guards and the thick walls of his lavish palace in Nineveh, the richly decorated stone sculptures of which can today be admired in the British Museum.

The royal scholar

Assurbanipal famously not only knew how to read and write, but was highly educated to the standard of a true scholar. In the words of a group of twelve scribes who helped him assemble the vast collection of cuneiform literature today known as Assurbanipal's Library he was learned in "the entire corpus of scribal learning, the craft of Ea PGP and Asalluhi PGP (i.e. the performing of rituals TT ), the divination series Šumma izbu TT and Šumma alu TT , the exorcistic TT corpus, the lamentation TT corpus, the song corpus and all other scribal learning", and similar statements can be found in his official inscriptions:

I learnt the lore of the wise sage TT Adapa PGP , the hidden secret, the whole of the scribal craft. I can discern celestial TT and terrestrial TT portents TT and deliberate in the assembly of the experts. I am able to discuss (the extispicy TT commentary) 'If the liver TT is a mirror image of the sky' with capable scholars. I can solve convoluted reciprocals and calculations that do not come out evenly. I have read cunningly written text in Sumerian, dark Akkadian, the interpretation of which is difficult. I have examined stone inscriptions from before the Flood TT , which are sealed TT , stopped up, mixed up.

Before his father Esarhaddon was chosen to inherit the Assyrian throne following the original crown prince Arda-Mullissi's PGP disqualification, young Assurbanipal, a boy at the time, may well have been destined for a priestly career. Several of his brothers later on held high functions in Assyrian and Babylonian temples, and Esarhaddon himself, with his deep interest in the workings of rituals and his scholars' work, quite possibly came from a similar background. But while there can be little doubt that all Assyrian kings were literate, just like all other men born into the higher echelons of society and destined for a role in the running of the empire, it is not at all certain that rulers like Sennacherib, Sargon II, and Tiglath-pileser III shared Assurbanipal's high level of learnedness and his fascination with esoteric and arcane knowledge. This interest, however, certainly prompted him to use his military successes in Babylonia and Egypt to collect, by sheer force when needed, whatever library texts were available and to have them brought to his growing palace library in Nineveh. So organised was this effort that the king had search parties dispatched to Babylonia in order to locate rare scholarly works. Whether he was motivated by a thirst for knowledge (and the wish to control this knowledge) or rather a collector's voraciousness, today the library he created remains his most lasting monument.

Further reading

- Lieberman,'Canonical and official cuneiform texts', 1990

- Livingstone, 'Assurbanipal', 2007

- Parpola, Letters from Assyrian scholars, IIA, 1971.

- Parpola, Letters from Assyrian scholars, 1970-1983.

Content last modified: 17 Apr 2024.

Karen Radner

Karen Radner, 'Assurbanipal, king of Assyria (669–c.630)', Knowledge and Power, Higher Education Academy, 2024 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/saao/knpp/Essentials/Assurbanipal/]