Babylon

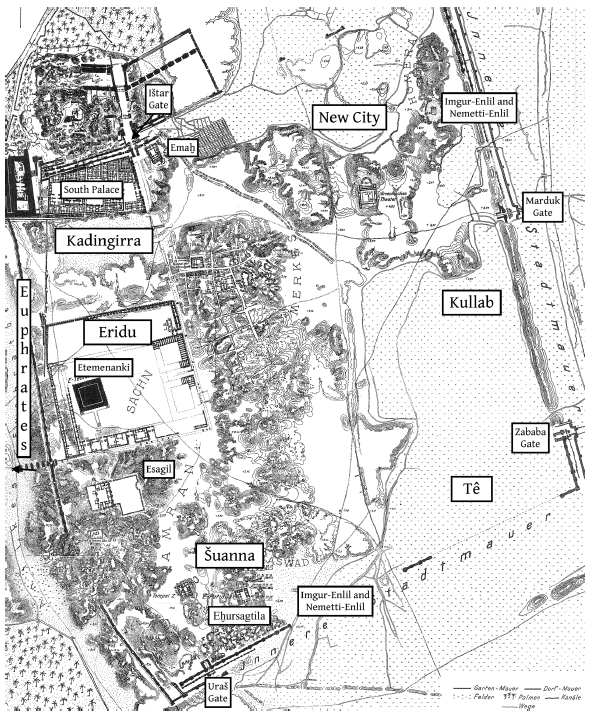

As to be expected, Babylon was the primary focus of Nabopolassar's building activities. Like many of his predecessors, he undertook construction on the city's inner and outer city walls, Imgur-Enlil ("The God Enlil Has Shown Favor") and Nēmetti-Enlil ("Bulwark of the God Enlil"), the double walls that surrounded Babylon that were built on the same circuit from at least the Second Dynasty of Isin (1157–1026) onwards, as well as the embankment wall(s) that ran alongside those mudbrick walls.[[22]] Akkadian inscriptions on clay cylinders (Npl. 1–5) and baked bricks (Npl. 8–12) attest to his efforts to restore and protect Babylon's walls; the stretch of wall between the Ištar Gate and the Zababa Gate, which ran beside the Araḫtu River, received a great deal of attention, as is clear from in-situ bricks, especially in the northwest corner of East Babylon, just north of the South Palace.[[23]] Because it had been a long time since either Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil had been worked on, it comes as little surprise that Nabopolassar dedicated a lot of time and resources to rebuilding Babylon's walls; according to textual sources, the walls were growing old and starting to collapse, due to aging and water damage (heavy rain).[[24]] The sun-dried-brick walls were built upon their (divinely-sanctioned) foundations. During the course of the work, the king's workmen discovered a statue of a former, unnamed king. That sculpture was said to have been placed back into the structure of the wall, together with his own (inscribed) statue.[[25]] As part of this work, Nabopolassar rebuilt the (eight) city gates of the inner city walls, including the Ištar Gate Ištar-sākipat-tēbîša ("Ištar Overthrows Its Assailant").[[26]] In order to better protect Babylon from water damage, he also actively reinforced the embankment wall, which is sometimes called the "Araḫtu embankment" (Akk. kār araḫti), with baked brick (and bitumen); that wall ran outside the entire circuit of Nēmetti-Enlil. In addition, Nabopolassar started construction on an outer city wall that provided additional protection to East Babylon.[[27]] Unfortunately for Nabopolassar, he did not live to see the completion of Babylon's walls; Nebuchadnezzar completed this work initiated by his father, whom he credits for starting these ambitious projects.

Nabopolassar, according to several inscriptions of his son, improved the processional streets.[[28]] For Nabû-dayyān-nišīšu ("The God Nabû Is the Judge of His People") — the processional street of the god Nabû, which is also called the street of the Uraš Gate[[29]] — and Ištar-lamassi-ummānīša ("The Goddess Ištar Is the Guardian Angel of Her Troops") — the processional street of the god Marduk, the so-called street of the Ištar Gate, a stretch of which also went by the name Ay-ibūr-šabû[[30]] — he improved these roads with a new paving of bricks. For the stretch of the processional road that was inside the Esagil complex from the Dais of Destinies ("Dukukinamtartarede ["Pure Mound, Where Destinies Are Decreed"]) to Kasikilla ("Pure Gate"), where the street joined Ay-ibūr-šabû/Ištar-lamassi-ummānīša, Nabopolassar is said to have paved that road with breccia slabs.[[31]]

In addition to work on Babylon's walls and streets, Nabopolassar is known to have undertaken construction on at least three buildings: The South Palace, the ziggurat Etemenanki ("House, Foundation Platform of Heaven and Underworld"), and the temple Eḫursagtila ("House Which Exterminates the Mountains"), all three of which were located in East Babylon. Presumably, he sponsored building on other temples, possibly on Esagil ("House Whose Top Is High"), Babylon's principal temple and the home of the city's tutelary deity Marduk. Nothing significant is known about Nabopolassar's work on the South Palace from the textual record, apart from the fact that Nebuchadnezzar II claims that he had built that royal residence's structure with unbaked bricks.[[32]] Because that building suffered from water damage (due to the high water table), as well as the fact that its gates were significantly lower than the street level since the procession street Ay-ibūr-šabû had to be raised several times, Nebuchadnezzar had to tear down what his father had constructed. The replacement palace was built anew with more durable materials (baked bricks and bitumen) and above the level of the groundwater and in line with the height of the directly adjacent processional way.

Figure 2. Annotated plan of the ruins of the eastern half of the inner city of Babylon. Adapted from Koldewey, WEB5 fig. 256.

In the most holy part of Babylon, the Eridu precinct, Nabopolassar started rebuilding Etemenanki, the sacred temple-tower of the god Marduk.[[33]] Before construction could begin, the king's workmen had to remove the massive brick structure of the ziggurat, which was old and in need of repair.[[34]] Once the demolition had been completed, well-trained specialists inspected the foundations, carefully measured the site, and after confirming the position of the (divinely-sanctioned) foundations through extispicy, Nabopolassar — together with his sons Nebuchadnezzar and Nabû-šumu-līšir — staged an elaborate ceremony to purify the building site and lay Etemenanki's new foundations, thereby kicking off the rebuilding. An inscription written on a three-column clay cylinder records some of the details:

By the time of his death in 605, Nabopolassar's workmen had raised the outer, baked-brick covering of the ziggurat's first terrace to a height of 15 m (30 ammatu). Like Babylon's walls, Nebuchadnezzar oversaw the completion of Marduk's ziggurat, a painstaking job that took many years to finish.[[36]]

In the Šuanna quarter of East Babylon, he constructed anew the Ninurta temple Eḫursagtila ("House Which Exterminates the Mountains").[[37]] Nabopolassar states that he had undertaken work on that sacred building since an unnamed former ruler — Ashurbanipal or possibly Esarhaddon (r. 680–669) — had started building the temple but had not completed its construction. If Ashurbanipal had been that previous builder, then it is probable that his workmen had work began on the temple (shortly) before his death in 631, which might explain why it was never finished.[[38]] Nabopolassar recorded that he completed the work on that temple — including roofing it (with beams of cedar), installing doors in its gateways, and decorating its interior, but it is uncertain, especially given the wording of royal inscription, whether or not this was actually the case. Given that Nebuchadnezzar does not mention working on Eḫursagtila in his own inscriptions, it is likely that work on Ninurta's temple at Babylon was completed prior to Nabopolassar's death.

22 This is clear from the find spots of the inscriptions of Marduk-šāpik-zēri (Frame RIMB 2 pp. 45–46 B.2.7.1 ii 7´) and his immediate successor Adad-apla-iddina (Frame RIMB 2 p. 51 B.2.8.1 line 3 [in broken context] ).

According to Esarhaddon's inscriptions, Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil formed a perfect square; however, the northern and southern stretches of the wall are 2,700 m in length, while the eastern and western sides are significantly shorter, being each 1,700 m in length. According to an inscription of Nabonidus (Weiershäuser and Novotny, RINBE 2 p. 54 Nbn. 1 [Imgur-Enlil Cylinder] i 22) , Imgur-Enlil measured "20 UŠ." An UŠ is a unit for measuring length, but its precise interpretation is uncertain since the sections of the lexical series Ea (Tablet VI) and Aa dealing with UŠ are missing. According to M. Powell (RLA 7/5–6 [1989] pp. 459 and 465–467 §I.2k), 1 UŠ equals 6 ropes, 12 ṣuppu, 60 nindan-rods, 120 reeds, and 720 cubits, that is, approximately 360 m; for UŠ = šuššān, see Ossendrijver, NABU 2022/2 pp. 156–157 no. 68. According to the aforementioned inscription of Nabonidus, Imgur-Enlil measured 20 UŠ (UŠ.20.TA.A), which would be approximately 7,200 m (= 360 m × 20). A.R. George (BTT pp. 135–136) has demonstrated that the actual length of Imgur-Enlil in the Neo-Babylonian period was 8,015 m, while O. Pedersén (Babylon p. 42 and 280) gives the length of the walls as 7,200 m, with the assumption that the stretches of walls within the area of palace are disregarded. In the time of Nabopolassar (and Nebuchadnezzar II), Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil were respectively 6.5 m and 3.7 m thick, with reconstructed heights of 15 m and 8 m. These impressive structures would have been made from an estimated 96,800,000 (Imgur-Enlil) and 28,500,000 (Nēmeti-Enlil) unbaked bricks. For studies of Babylon's inner walls from the textual sources and the archaeological remains, see George, BTT pp. 336–351 (commentary to Tintir V lines 49–58, which are edited on pp. 66–67); and Pedersén, Babylon pp. 39–88.

23 See Figure 12 on p. 57 for the find spots of Npl. 8 and 11–12.

24 The last known major rebuilding of these walls took place during Esarhaddon's reign and the very beginning of Ashurbanipal's, therefore, it had been about forty to fifty years since Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil had been properly attended to.

25 Npl. 3 (C32) iii 16–21. For details, see Beaulieu, Eretz Israel 27 (2003) pp. 1*–9*.

26 Nbk. 24 (C012) i´ 1´–14´.

27 Traces of the eastern outer wall are still visible to this day. However, only a small portion of this 7.5-km-long wall that protected the eastern half of Babylon and doubled that city's size has been explored. During the German excavations of Babylon under the direction of R. Koldewey in 1899–1917, only 800 m of that wall was investigated. None of its five gates have been positively identified. The new outer wall consisted of a 7-m-wide unbaked mudbrick wall, a 7.8-m-wide baked-brick quay wall, a 3.3-m-wide quay, and a wide moat. The estimated maximum height of the wall is 13 m. Moreover, it has recently been estimated that the eastern outer wall, together with its quay wall, was built from as many as 96,600,000 mudbricks and 117,700,000 baked bricks. Most of the work appears to have been carried out while Nebuchadnezzar II was king. For further details, see Pedersén, Babylon pp. 44, 53, 57–60, and 88.

28 Nbk. 2 (East India House) v 12–20; see also the B13 inscription (George, BTT p. 363). For further details on Babylon's streets, see George, BTT pp. 358–367.

29 Nabû-dayyān-nišīšu ran south-north from the Uraš Gate (Ikkibšu-nakari) to Nabû's entrance into the Esagil complex, on the southern side.

30 Ištar-lamassi-ummānīša ran north-south from the Ištar Gate (Ištar-sākipat-tēbîša) to Kasikilla, the main, eastern entrance to the Esagil complex. For the use of both Ištar-lamassi-ummānīša and Ay-ibūr-šabû for the same stretch of road, see George, BTT p. 364.

31 That road might have gone by the Akkadian name Išemmi-ana-rūqa ("He Listens to the Distant"). For the suggestion that this street of Marduk, which is mentioned in Tinir = Babylon V line 81, was part of the processional street, see George, BTT p. 367.

32 Nbk. 2 (East India House) vii 34–56. For information about the South Palace, which was in the Ka-dingirra district, see Pedersén, Babylon pp. 71–87.

33 Npl. 6 (C31) i 28–iii 33; Npl. 13 (B6) lines 13–18; and Nbk. 27 (C41) ii 1–18. For further details about the textual sources and the archaeological remains, see Wetzel and Weissbach, Hauptheiligtum; George, BTT pp. 298–300 (the commentary to Tintir IV line 2, which is edited on pp. 58–58) and 430–433 (commentary to the Esagil Tablet lines 41–42, which are edited on pp. 116–117); and Pedersén, Babylon pp. 142–165.

34 The base of Etemenanki measured 91.5 × 91.5 m (ca. 8400 m²). The core of unbaked mud bricks was surrounded with a 15.75-meter-thick baked-brick outer mantle. Information about Etemenanki prior to the Assyrian domination of Babylonia (728–626) is very sparse and comes entirely from narrative poems (Enūma Eliš and the Poem of Erra) and scholarly compilations (Tintir = Babylon) and, thus, it is not entirely certain when Marduk's ziggurat at Babylon was founded. It has often been suggested that Nebuchadnezzar I (1125–1104), the fourth ruler of the Second Dynasty of Isin, was its founder; this would coincide with the period during which Enūma eliš is generally thought to have been composed. Given the lack of textual and archaeological evidence, this assumption cannot be confirmed with any degree of certainty and one cannot rule out the possibility that the Etemenanki was founded much earlier, perhaps even in Old Babylonian times. Esarhaddon is the first known builder of Marduk's ziggurat.

35 Npl. 6 (C31) ii 31–iii 24.

36 In the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II, Etemenanki is sometimes thought to have had seven stages, six lower tiers with a blue-glazed-brick temple construction on top; for a discussion and digital reconstructions, see Pedersén, Babylon pp. 153–165. Given the lack of archaeological evidence, it is uncertain how many tiers this temple-tower actually had. See n. 116 below.

37 Npl. 7 (C12) lines 22–30. For details on the temple, see George, House Most High p. 102 no. 489; and Pedersén, Babylon pp. 190–193.

38 No remains of this stage of the temple's history ("Level 0") have been excavated. The earliest phase of construction ("Level 1") dates to the time of Nabopolassar. See Pedersén, Babylon pp. 190–193 for details. Note that a single brick inscribed with a Sumerian inscription of Esarhaddon (BE 15316; Leichty, RINAP 4 pp. 256–258 Esar. 126 ex. 1) was discovered in the Ninurta temple, in the south gate, courtyard door, which might point to Esarhaddon having worked on Eḫursagtila. Despite Aššur-etel-ilāni's short reign, one cannot entirely exclude the possibility that that Assyrian king, rather than his father or grandfather, undertook construction on this temple of Ninurta. However, given the current textual record, it seems more likely that Ashurbanipal was the unnamed previous building of Eḫursagtila.

Jamie Novotny & Frauke Weiershäuser

Jamie Novotny & Frauke Weiershäuser, 'Babylon', RIBo, Babylon 7: The Inscriptions of the Neo-Babylonian Dynasty, The RIBo Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, 2024 [/ribo/babylon7/RINBE11Introduction/Nabopolassar/BuildingActivitiesofNabopolassar/Babylon/]