Survey of the Inscribed Objects

At least twenty-five sites,[[102]] the majority of which are in present-day southern Iraq, have yielded objects inscribed, carved, or stamped with Neo-Babylonian royal inscriptions written in Akkadian.[[103]] Almost all inscriptions included in the present volume originate from Babylon. The only exceptions are two texts of Nabopolassar (Npl. 14–15), which come from Sippar. While the bulk of Nabopolassar's inscriptions originate from Babylon, those of Nebuchadnezzar come from a much larger number of sites (for example, Babylon, Borsippa, Isin, Kish, Larsa, Marad, Nahr el-Kalb, Persepolis, Sippar, Ur, Uruk, and Wadi Brisa). As mentioned above, this volume only contains some of the inscriptions of Nebuchadnezzar from Babylon, his administrative capital and, therefore, the Survey of Inscribed Objects presented here only deals with the texts edited in RINBE 1/1; the inscribed objects of Nebuchadnezzar included in Part 2 will be discussed in the introduction of that book.

As for how these texts came to light, many of the objects originate from (1) the German excavations at Babylon directed by Robert Koldewey for the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft (DOG) and the Königliche Museen Berlin (KMB) in 1899–1917; (2) Iraqi excavations led by Muayad Said Damerji at Babylon in the late 1970s and early 1980s; (3) the British Museum excavations conducted by Hormuzd Rassam between 1879 and 1882, especially at Sippar in 1881–82; and (4) objects purchased on the antiquities market in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.[[104]]

| Origin | Text No. |

|---|---|

| German excavations | Npl. 1.1, 5–6; Npl. 5; Npl. 7.1–5; Npl. 8.1–6; Npl. 9.1–3*; Npl. 10.1–31; Npl. 11.1–12; Npl. 12.1–29; Nbk. 3.1–6; Nbk. 4; Nbk. 5.1–15; Nbk. 6.1–2; Nbk. 7.1–10; Nbk. 8.2; Nbk. 9.1–15; Nbk. 11.1–1*; Nbk. 12.5–7; Nbk. 14.2; Nbk. 15.1; Nbk. 18.1, 3; Nbk. 20; Nbk. 21.3–5, 7, 9–12; Nbk. 22.1–2, 1*; Nbk. 27.3, 6–7; Nbk. 30.2–3; Nbk. 36.3–13; Nbk. 38–43, 45–56 |

| Iraqi excavations | Npl. 1.3–4; Npl. 2.1–5; Npl. 3; Nbk. 14.1; Nbk. 15.2–3; Nbk. 27.9; Nbk. 33; Nbk. 34.1–3 |

| British excavations | Npl. 14.1–5; Npl. 15; Nbk. 12.4; Nbk. 13.18; Nbk. 15.4–5; Nbk. 17; Nbk. 26; Nbk. 29.8, 15–16 |

| Other excavations | Npl. 6.1; Nbk. 27.2 |

| Purchased | Npl. 1.2, 7; Npl. 4; Npl. 6.2; Npl. 7.6; Npl. 13; Nbk. 1; Nbk 2.1–3; Nbk. 8.1, 3; Nbk. 10; Nbk. 12.1–3; Nbk. 13.1–17; Nbk. 16; Nbk. 18.2; Nbk. 19; Nbk. 21.1–2, 6, 8; Nbk. 22.3; Nbk. 23.1–5; Nbk. 24–25; Nbk. 27.1, 4–5, 8, 10–14; Nbk. 28; Nbk. 29.1–7, 9–14, 17–30; Nbk. 30.1; Nbk. 31–32; Nbk. 35.1–3; Nbk. 36.1–2; Nbk. 37; Nbk. 44 |

The bulk of these inscribed objects are now housed in the British Museum (London), the Eşki Şark Eserleri Müzesi of the Arkeoloji Müzeleri (Istanbul), and the Vorderasiatisches Museum (Berlin), while a significant portion of the RINBE 1/1 exemplars have made their way into the Iraq Museum (Baghdad), the Musée du Louvre (Paris), the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York), the Nebuchadnezzar Museum (Babylon), the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (Philadelphia), and the Babylonian Collection of Yale University (New Haven). Other Neo-Babylonian inscriptions edited in this volume are scattered throughout various European, Middle Eastern, and North American institutions. Lastly, a number of the clay and stone objects included in RINBE 1/1 are likely lost forever since they were either left in situ (for example, bricks, paving stones, and stone blocks unearthed at Babylon), made their way into a private collection, or were never properly documented (for example, Npl. 13 [B6]).

The texts included in the present volume are inscribed, carved or stamped on seven different types of clay and stone objects (see the chart immediately below). As is well known, baked bricks and clay cylinders are the best attested media of Neo-Babylonian royal inscriptions.

| Object Type | Text No. |

|---|---|

| Clay cylinders (originals) | Npl. 1–7, 14 (exs. 1–4), 15; Nbk. 12 (exs. 2, 4–7), 13 (exs. 6–7, 9, 18), 14–28, 29 (exs. 2, 4–5, 20–21, 23, 27–29), 30–56 |

| Clay cylinders (casts/replicas) | Nbk. 12 (exs. 1, 3), 13 (1–5, 8, 10–15, 17), 29 (exs. 1, 6–19, 22, 25) |

| Clay Prisms | Nbk. 11 |

| Baked Bricks | Npl. II 8–13, 14 (ex. 5) |

| Stone Stele | Nbk. 1 |

| Stone Tablets | Nbk. 2 |

| Stone Blocks | Nbk. 3–4 |

| Stone Paving Stones | Nbk. 5–10 |

Neo-Babylonian royal inscriptions are written in cuneiform script, as one expects from compositions written in Akkadian.[[106]] The scribes who wrote out the texts included in this volume used either a contemporary Babylonian script or an archaizing one that was inspired by Old Babylonian monuments (for example, the Code of Ḫammu-rāpi).[[107]] Very few inscriptions, however, were written using both contemporary and archaizing scripts.

| Script | Text no. |

|---|---|

| Contemporary Neo-Babylonian | Npl. 5, 7; Nbk. 11–24, 26, 29, 31–56 |

| Archaizing Neo-Babylonian | Npl. 1–4, 6, 8, 10–11, 14–15; Nbk. 1–10, 27–28, 30 |

| Contemporary and Archaizing Neo-Babylonian | Npl. 9, 12 |

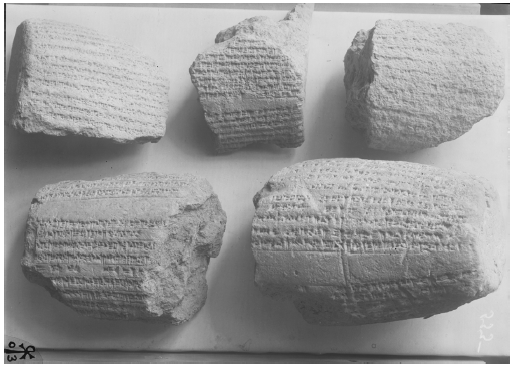

Bab ph 555, which shows five clay cylinder fragments, including those with Nbk. 21 ex. 3, Nbk. 36 exs. 3 and 7, and Nbk. 51 ex. 1. © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Vorderasiatisches Museum, Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft. Photo: Robert Koldewey, 1904.

102 R. Da Riva (GMTR 4) lists the following provenances for Neo-Babylonian inscriptions: Iraq: Babylon, Borsippa, Eridu, Habl as-Sahr, Isin, Kish, Kissik, Larsa, Marad, Nasiriyah, Seleucia, Sippar, Tell Nashrat-Pasha, Tell Uqair, Ur, and Uruk; Turkey: Ḫarrān; Lebanon: Nahr el-Kalb, Wadi Brisa, Shir Sanam, (Wadi as-Sabaʿ); Jordan: Selaʿ; Iran: Persepolis, Susa; and Saudi Arabia: Tēmā and al-Hayit. She notes that the list is not exhaustive, especially since many objects were purchased from the antiquities market.

103 To date, no Sumerian or bilingual Akkadian-Sumerian inscriptions have been discovered for the kings of the Neo-Babylonian Empire. Thus, all royal inscriptions from this time were composed in the Standard Babylonian dialect of Akkadian. For further details on the language of the inscriptions, see Da Riva, GMTR 4 pp. 89–91.

104 For a general overview, see, for example, Da Riva, GMTR 4 pp. 60–63.

105 R. Da Riva discusses the different material supports of Neo-Babylonian royal inscriptions in GTMR 4; see pp. 33–43 of that book.

106 For an overview of the scripts used for Neo-Babylonian royal inscriptions, see, for example, Da Riva, GMTR 4 pp. 76–79.

107 It has been suggested that the Old Babylonian monumental script of the Codex Ḫammu-rāpi, even though it had been carried off to Susa by the Elamites in the twelfth century, had a strong influence on the script used for writing out Neo-Babylonian royal inscriptions; see, for example, Berger, NbK p. 95; Schaudig, Inschriften Nabonids p. 32 n. 133; and Da Riva, GMTR 4 p. 77 n. 77. As R. Da Riva has pointed out, the use of Old Babylonian sign forms is an archaism that diminishes over the course of the Neo-Babylonian Period. During the reigns of Nabopolassar and Nebuchadnezzar II, archaizing scripts were more common for royal inscriptions than during the reigns of their successors.

Jamie Novotny & Frauke Weiershäuser

Jamie Novotny & Frauke Weiershäuser, ' Survey of the Inscribed Objects ', RIBo, Babylon 7: The Inscriptions of the Neo-Babylonian Dynasty, The RIBo Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, 2024 [/ribo/babylon7/RINBE11Introduction/SurveyoftheInscribedObjects/]