Mound A: the Sumerian Palace

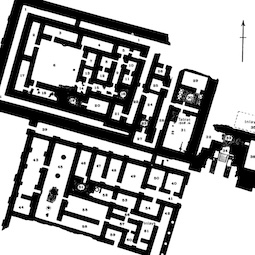

Mound A is the name given to what was once a low and irregular mound "shaped like the letter S", close to the large ziggurat of the temple of Ishtar on Tell Ingharra (Mackay 1925: 9). When it was excavated by the OFME from 1923, this mound became famous as the location of a sumptuous Sumerian palace, dating to the Early Dynastic III period, c. 2500 BC, and of an extensive cemetery discovered on top of the palace walls, used for a short period after the palace was abandoned.

The excavation team

[/kish/images/mounda-basketboys-large.jpg]

[/kish/images/mounda-basketboys-large.jpg]Figure 1: Plan of the Sumerian Palace on Mound A at Kish. Source: Moorey 1978: 57, based on Mackay 1929 pl. XXI-XXII

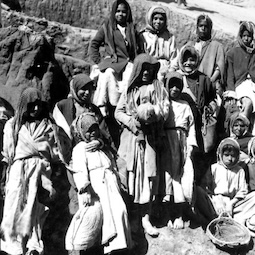

The OFME began their excavation of Mound A in January 1924. On previous visits the year before, they had been struck by the quantity of broken pottery sherds, brick fragments, and flints which covered the ground, and they had decided to test this area. The excavation was initially conducted by two groups of nine men and boys. Each group included "one pickman" who was the group leader, "two shovelmen", and "six boys" (Mackay 1929: 77). According to Mackay, all the pickmen came from Kuwairish, a village close to Babylon, and all were experienced excavators. They had previously worked with the German excavation team at Babylon, and had probably excavated other sites also before then. The shovelmen and boys assigned to carry baskets of soil ("basket-boys" as they were then called) came from Kish.

[/kish/images/mounda-basketboys-large.jpg]

[/kish/images/mounda-basketboys-large.jpg]Figure 2: "Basket boys" at Kish, undated. Source: OFME Photo Album, ANT 140, p. 134, negative 59674.

Mackay recounts that one man became especially famous for his skills on site. When the team first began to dig, their focus was on finding walls and doorways to delimit the palace layout. But the mudbrick walls were in such poor condition that it was difficult to see them and not destroy them. One team member however, whose name is not preserved in reports, had such "exceptional flair" for finding walls and doorways in fragile clay that he led the team during the entire part of the last season. As results show, he was tremendously successful (Mackay 1929: 78). By the end of March 1925, the entire palace was cleared (Mackay 1929: 75). The names of all the boys and men are unfortunately not preserved in reports, but a few photos survive in the OFME archive.

The architecture of the Sumerian Palace

[/kish/images/mounda-palace-ne-large.jpg]

[/kish/images/mounda-palace-ne-large.jpg]Figure 3: "Foundation of a Sumerian palace from the northeast", undated. Source: OFME Photo Album, ANT 140, p. 45, negative 49218.

Today, nothing remains of the palace, but reports and photographs of the excavation show that its architectural features were impressive. The palace once had a large facade and a stairway constructed with plano-convex bricks. It contained over 60 rooms, many of them decorated with shell and friezes depicting celebrations and banquets.

[/kish/images/mounda-stairway-large.jpg]

[/kish/images/mounda-stairway-large.jpg]Figure 4: "View of stairway of Palace A", undated. Source: OFME Photo Album, ANT 140, p. 41, negative 68317.

The whole palace was built with plano-convex bricks, including its foundations and upper walls. It was built in three stages. First, a wing to the west, the earliest part, which Mackay called the northern block (rooms 1-31). Then, a monumental entrance and additional rooms were added (rooms 32-38). Later still, an annex with pillared portico was built to the south of the original building. Archaeologists call this area the southern block (rooms 39-60). This annex was strongly fortified, with towers at intervals on its double exterior walls (Gibson 1972: 78).

[/kish/images/mounda-facade-large.jpg]

[/kish/images/mounda-facade-large.jpg]Figure 5: "Facade of Palace A", undated. Source: OFME Photo Album, ANT 140, p. 33, negative 206.

When the ancient architects added the annex, they had to raise the ground level, and the stairway on the eastern end could no longer be used. Instead, it was turned into a ramp. But when the OFME cleared it to find the original stairs, they could tell it had once been made of eight steps which led to a spacious entrance (room 34) and then onto chambers and passages on the east and west. But this side of the palace was in bad shape when it was found. It had already been swept away by the weather (Mackay 1925: 91). Only three chambers survived (rooms 36, 37, 38). On the outer walls, the team also discovered a buttress, and a facade inlaid with niches.

[/kish/images/mounda-niches-large.jpg]

[/kish/images/mounda-niches-large.jpg]Figure 6: "Niches in Facade of Palace A", undated. Source: OFME Photo Album, ANT 140, p. 38, negative 226.

Inlays

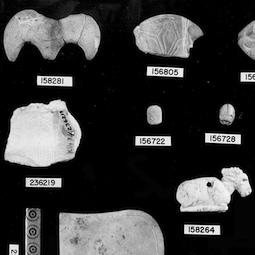

[/kish/images/mounda-inlays-large.jpg]

[/kish/images/mounda-inlays-large.jpg]Figure 7: Some of the inlay fragments found in the Sumerian Palace at Kish that are now in the Field Museum, Chicago. Undated photo from the OFME. Source: Field Museum digital assets website [https://fm-digital-assets.fieldmuseum.org/81/218/a88486.jpg].

The OFME team also discovered that many of the palace walls had once been plastered white stuccos, the material we now call juss in Iraq (Mackay 1929: 107). This background was used to decorate the walls with inlays made of mother-of-pearl, shell, and other delicate and precious materials. Many of these fragments were found on the rooms' floors.

For Mackay, one of the most interesting examples of inlays was one discovered in the corner of chamber 35. Made of fine white limestone, it is broken but surprisingly large, 64 cm x 33 cm, and 3cm thick (Mackay 1929: 120). It depicts a king with his right foot slightly raised, resting upon something which is unfortunately broken, perhaps an enemy, like the Assyrian king Naram-Sin in the Stele of the Vultures. This object [https://www.ashmolean.org/collections-online#/item/ash-object-461501] is now in the collection of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

Women are also depicted in this scene. Their eyes were made of lapis-lazuli. Beautifully dressed, wearing necklaces, diadems, and earrings, the women hold a particular kind of cup in their hands, with a pointed base. Mackay's team found similar pottery cups in the palace (Mackay 1929: 123).

Fragmentary inlays also represent musicians and musical instruments. In cuneiform texts, Kish is known for a special musical instrument called the urzababitum, named after the famous king of Kish, Ur-Zababa, in a praise poem composed for king Shulgi [https://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.2.4.2.02&display=Crit&charenc=&lineid=t24202.p14#t24202.p14] in the 21st century BC (Franklin 2016: 77). Musicians were important state functionaries. Cuneiform texts tell us that during the pre-Sargonic period (2700-2350 BC) and the Old Babylonian period (2004-1595 BC), musicians travelled between Kish, Mari, Ebla, as well as other towns, to perform at state banquets (Ziegler 2007).

The Hall of Columns

[/kish/images/mounda-pillars-large.jpg]

[/kish/images/mounda-pillars-large.jpg]Figure 8: "Pillared Hall, South West, Palace A", undated. Source: OFME Photo Album, ANT 140, p. 44, negative unnumbered.

One of the most striking architectural features of the palace was its columns. At the time, Mackay called them "a unique discovery in Sumerian architecture" (Mackay 1929: 99). They were made not only as structural support for the ceiling but to decorate. All were found in a remarkably good state of preservation. Their height had been diminished by time, but many still averaged 70 cm above their base, and some were even higher. Hall 5, for example, had four columns in its centre, each 1.50 m in diameter, with the most northerly column standing at a height 1.80 m above the brick pavement (Mackay 1929: 95).

The end of the palace's occupation

Few objects were found in the palace. Mackay called it a "very disappointing site as regards the finding of movable objects" (Mackay 1929: 62). This is not unusual in Mesopotamian buildings, but Mackay did find this strange because, even if the palace had been looted in antiquity, people would have taken the most valuable objects, but they would not have emptied every single room. What happened to the palace's ancient residents, and why did the palace stop being used in the first place?

In 1929, Mackay recorded that he had found evidence that both the original side of the palace and its annex were attacked, possibly on more than one occasion. But in 1972, Gibson remarked he saw "little evidence of destruction by enemies or fire as did Mackay. There is no sign of burning on the walls still standing" (Gibson 1972: 79). Instead, Gibson suggested that the reason so few objects were discovered in the building is because this was the sign of as an orderly clearing up, not a sacking.

Based on archaeological evidence, the palace was abandoned in the Early Dynastic period IIIb (2540-2350 BC). But Mound A continued to be occupied, including in the second and first millennia BC, with traces of occupation in the Abbasid period also (Gibson 1972: 79). But before this, a few hundred years after the palace residents left, the area was used as a cemetery for a short period.

The cemetery

[/kish/images/mounda-cemetery-large.jpg]

[/kish/images/mounda-cemetery-large.jpg]Figure 9: "The "A" Cemetery seen from the Large Ziggurat, Tell Ingharra", undated. Source: OFME Photo Album, ANT 140, p. 9, negative 49184.

When the OFME team began to dig on Mound A, they first discovered that the surface of the mound was pierced by graves. The graves were laid on top of the Sumerian Palace, after it was abandoned for a few hundred years. The cemetery was used for only two or three generations in the third millennium BC, between c. 2430 BC and c.2330 BC (Early Dynastic IIIb up to the early Akkadian period) according to Moorey 1978: 104).

By the end of the excavation Mackay had recorded 154 burials, but noted there were many more left unexplored. The graves contained human remains as well personal objects that families buried with their loved ones four and a half thousand years ago.

In this section, we will only briefly describe finds made in Cemetery A, and wish to warn visitors and readers that the collection of this material was carried out when Iraq was under colonial rule. In the early twentieth century, archaeological practice prioritized the discovery of objects, including human remains, to enrich museum collections, and studies of past customs and cultures. Today, ethical concerns over such collections are not only changing archaeological practice but also opening debates about consent and cultural representation19. These days, even ancient human remains are treated with dignity and respect.

Since their removal, the human remains of "Cemetery A" have been housed in the collection of the Field Museum of Chicago, along with most of the objects found in these graves. Their scientific analysis led to a variety of studies, from research on health based on teeth, to mortuary practices and demography at Kish. But all results have suffered from the lack of reliable stratigraphical data and of the archaeological contexts of these finds. This information was not collected during the excavation or published in reports.

Bioarchaeological studies have confirmed that the human remains at Cemetery A are those of adult males, females, as well as children. The deceased were not buried in coffins, but in reed matting. Their bodies were then placed in rectangular graves made of bricks or mud flooring (Pestle, Torres-Rouf, Daverman 2023). Their graves were rich in objects, for example cylinder seals, pottery, figurines, tools, weapons, as well as personal articles such as household objects like spindles and dishes, and personal ornaments like hair pins, earrings, finger-rings, nose ornaments, and beads.

Some of the jars discovered were especially remarkable. For example, a "goddess-handled vessel" was discovered in grave 52 (Gibson 1972: 79, fn 126).

15 Sep 2025

Nadia Aït Saïd-Ghanem

Nadia Aït Saïd-Ghanem, 'Mound A: the Sumerian Palace', The Forgotten City of Kish • مدينة كيش المنسية, The Kish Project, 2025 [http://oracc.org/MoundsofKish/TellIngharra/SumerianPalace/]