The Tablet Mound (Mound W) and the so-called "Library"

The large mound to the west of Tell Ingharra is known as Mound W on archaeological maps of Kish, or more informally as Tell Antika, "Mound of Antiquities" (Gibson 1972: 119). The OFME also called it the "Tablet Mound". Today, it is separated from the rest of the site by the L-shaped road which leads to Highway 1, the longest highway in Iraq. Mound W is not open to visitors but it is clearly visible from the top of any of the three ziggurats as it lies directly between Tell Ingharra and Tell Uhaimir. It is distinguished by the large date groves that occupy the dry bed of the watercourse that used to flow north-south through the ancient city.

[/kish/images/moundw-fig2-large.jpg]

[/kish/images/moundw-fig2-large.jpg]1. "Excavation of Tablet Mound", undated. Source: OFME Photo Album, ANT 140, p. 77, negative number 68041.

As with most tells at Kish, this mound was occupied for thousands of years, possibly from as early as the Early Dynastic period until the Achaemenid period (538-331 BC), with evidence of Parthian and Early Islamic occupation too (Gibson 1972: 120; Moorey 1978: 48; Zaina 2020: 138). But it is the finds from the Neo-Babylonian and early Achaemenid periods (7th-5th centuries BCE) that are the most plentiful.

Excavations on Mound W

[/kish/images/moundw-fig2-large.jpg]

[/kish/images/moundw-fig2-large.jpg]1. "Excavation of Tablet Mound, workers and staff", undated. Source: OFME Photo Album, ANT 140, p. 78, no negative number.

Mound W was made famous when the OFME discovered hundreds of cuneiform tablets in early 1924, during one of expedition director Professor Stephen Langdon's rare visits to the site. While Ernest Mackay was uncovering the Sumerian Palace on Mound A, carefully documenting his finds according to the modern archaeological method advocated by his former mentor Sir Flinders Petrie, just a few hundred metres away, Langdon—an Assyriologist rather than an archaeologist—adopted a much more traditional approach. As Moorey (1978: 48) puts it, "Langdon was only interested in digging out tablets and paid attention neither to their archaeological context nor to their associations."

In February 1924, a member of the team (unnamed in reports) discovered a tablet to the south of the mound. Langdon's attention focused on this area for four weeks with no other finds made, until his team moved further north and discovered a large deposit of cuneiform tablets, mostly literary texts. As they progressed toward the centre of the mound, they came upon a large building containing tablets in almost every room. These were stored in large jars arranged round the rooms according to contents, primarily syllabaries and religious compositions (Moorey 1978: 48-49).

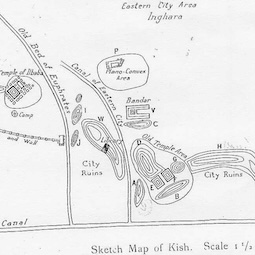

[/kish/images/moundw-fig3-large.jpg]

[/kish/images/moundw-fig3-large.jpg]3. Langdon's sketch map of Kish, showing the so-called "library" only as a block on the south-west of Mound W. The map is not to scale. Source: Langdon 1924: pl. 33 top.

Langdon described the building as a "library building" or complex. According to Watelin's later notes, it measured 30.4 m along one side with walls apparently surviving up to 4.40 m high (Moorey 1978: 49). Unfortunately, Langdon did not commission any architectural plans, or record the location of any of the tablets within it so the nature of this building is impossible to confirm today (Figure 3). However, the impressive height of the walls, the storage arrangements, and the contents of the tablets, together suggest that this was a temple annexe housing a scholarly community's ritual offerings of finished works from the Neo-Babylonian period, c.720–500 BC (see Robson 2019: 164–7, 210–15).

The rooms also contained other objects. For example, figurines of Papsukkal, the attendant deity to the god Anu, and small dog figurines, all inscribed in cuneiform and made of baked clay. These had almost certainly been buried in the foundations of the building in ancient times, in order to ward off evil. Pottery glazed in a pale smoky blue colour was also found. Some examples are in the Iraq Museum in Baghdad (Moorey 1978: 50).

In the following season, the OFME cleared what seemed like a sizable town on the end south of the mound. The archaeologists thought the buildings they unearthed were houses, and gave some of them numbers, but did not keep any information about what they found there.

The cuneiform tablets from Mound W

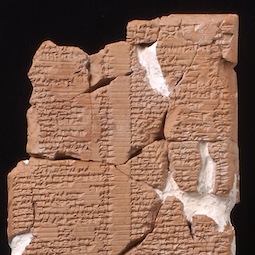

[/kish/images/moundw-fig4-large.jpg]

[/kish/images/moundw-fig4-large.jpg]4. A cuneiform tablet found somewhere in Mound W, containing Chapter 1 of the Babylonian Epic of Creation. It has been pieced together from many small fragments and much is still missing. Source: Ashmolean Museum AN 1924.790 obverse, photo taken for Eleanor Robson in 2003.

The tablets found at Mound W are of many different types: letters, contracts, accounts, as well as scholarly works and fragments of school texts. Although Moorey estimates that over half of the two thousand tablets excavated by the OFME originate from Mound W, poor record-keeping means that fewer than 300 can now be assigned to this tell. In 2004 Eleanor Robson provisionally identified about 80 long, thin Neo-Babylonian "library tablets" that presumably formed the core of the scholarly collection on this site and are now housed in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. The works they contain range from the Babylonian epic of creation, Enūma Eliš (Figure 4), to incantations, prayers and rituals, as well as omens, astronomy and mathematics (Robson 2004).

Many of the legal contracts found on Mound W end with the date on which they were written, so we can tell that they were written during the reigns of the Persian kings Cambyses, Darius, Xerxes and Artaxerxes I, who ruled Babylonia in the perios 529-424 BC. You can read many of them in English, Arabic, and Persian translation as well as in the original Akkadian and Sumerian in the Kish Corpus.

The Cemetery on Mound W

[/kish/images/moundw-fig5-large.png]

[/kish/images/moundw-fig5-large.png]5. "Clay coffins in Tablet Mound", undated. Source: OFME Photo Album, ANT 140, p. 81, negative number 29.

Between 1924 and 1932, the OFME also unearthed an extensive cemetery on the upper levels of the mound. Father Eric Burrows led the excavation of the cemetery in Langdon's absence during the OFME's third season. The burials discovered are similar to those found on Mound A and on Tell Ingharra (Moorey 1978: 49). In total, 87 burials were recorded, all from the fifth to fourth centuries BC. The coffins found are called "bath-tub" type coffins (Figure 5). These have been found used in many sites in Iraq, for example at Nippur and Babylon in the Neo-Assyrian period, and at Ur in the Achaemenid period.

The OFME team was especially impressed with the discovery of two glass vessels dated from the 7th or 6th century found in two separate graves. One is in the Iraq Museum (IM 2277, found in grave 23), and is very similar to vessels found at Ur. The other is in the Field Museum of Chicago (Field 230904).

15 Sep 2025

Nadia Aït Saïd-Ghanem & Eleanor Robson

Nadia Aït Saïd-Ghanem & Eleanor Robson, 'The Tablet Mound (Mound W) and the so-called "Library"', The Forgotten City of Kish • مدينة كيش المنسية, The Kish Project, 2025 [http://oracc.org/MoundsofKish/TabletMound/]