Knowledge repatriation and the written heritage of ancient Iraq

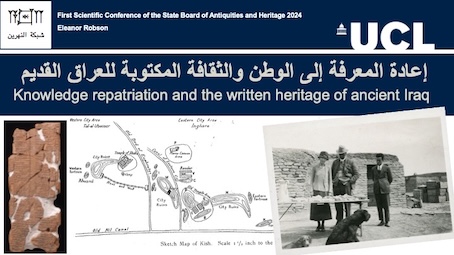

This is a lightly edited version of a talk given by Eleanor Robson at the First Scientific Conference of the Iraqi State Board of Antiquities and Heritage (SBAH), held at the University of Mosul on 29–30 May 2024 (Figure 1). We are particularly grateful to Ustadh Ali Shalgham and his team at SBAH for organising this important event, and to Dr Laith Hussein for so ably chairing the session at which it was presented.

A longer, more theoretically grounded version of this argument will appear in the open-access series Cambridge Elements in Critical Heritage Studies, in both English and Arabic, in 2026.

[/kish/images/knowrep-fig1-large.jpg]

[/kish/images/knowrep-fig1-large.jpg]Figure 1: Title slide for the original talk on Knowledge Repatriation and the Written Heritage of Ancient Iraq, given in May 2024 at the University of Mosul. Click or tap the image to enlarge it.

Introducing "Knowledge Repatriation"

Here I would like to introduce the concept of knowledge repatriation and explain how it relates to the written heritage of ancient Iraq. I will describe the problem it addresses, using the archaeological site of Kish as a case study, and some of the long-term, often intractable consequences of that problem. Finally, as a non-Iraqi, I hope these ideas will open a dialogue about how international researchers and heritage institutions can collaborate, through the State Board of Antiquities and Heritage, and through Iraq's universities, to make knowledge repatriation not just a concept but a useful and effective practice.

Every Iraqi is familiar with the concept and practice of repatriating archaeological artefacts. Over the past few years, thanks to the tireless efforts of SBAH's lawyers, many thousands of cuneiform tablets, amongst other objects, have been returned to Iraq. Some were smuggled from Iraq, like the infamous Hobby Lobby collection [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hobby_Lobby_smuggling_scandal]; others were taken from the country on very long-term study loan, like the tablets from Ur returned by the British Museum in 2023 [https://ane.hypotheses.org/11875]

In almost every case, though, people studied those tablets while they were in international collections, catalogued and edited and published them. Shouldn't that knowledge return to Iraq too? Why should Iraqis be burdened with recreating work that has already been done?

This is what I mean by knowledge repatriation. But what types of knowledge matter? And how should they be returned with the artefacts that come back? In fact, once we stop to think about it, knowledge about Iraq's past, and about cuneiform tablets and other archaeological artefacts, can and should be repatriated independently of whether or not the objects are able to return.

Archaelogical knowledge extraction and destruction: the sad case of Kish

There were two major long-running British excavation projects in Iraq during the Mandate period of the 1920s to early 30s. Leonard Woolley's PGP expedition to Ur [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leonard_Woolley#Excavation_at_Ur], for the British Museum and Penn Museum, is well known and often celebrated for its discoveries and advancement of knowledge. But at exactly the same time, the University of Oxford and the Field Museum in Chicago ran a similarly ambitious archaeological expedition to Kish. Oddly though, the leader of the Kish expedition, Professor Stephen Langdon PGP , had never travelled to the Middle East, and had never run an excavation. It's no wonder that the project it turned out so badly.

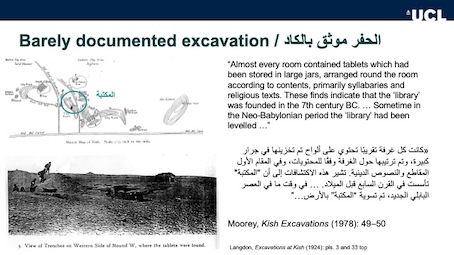

For instance, Figure 2 summarises all we know about what must have been a really important find of Neo-Babylonian cuneiform tablets between 1923 and 1926. Langdon made no archaeological plan, just a terrible sketch map of the whole site, and photo showing its rough location on Mound W.

In the 1970s, Roger Moorey tried to summarise what the excavators must have found, and about 20 years ago I compiled a list of about 60 tablets in the Ashmolean Museum that probably came from this library (Moorey 1978; Robson 2004). But so much information has been lost, about this huge and important archaeological site, due to recording practices that were deeply inadequate, even by the standards of the time.

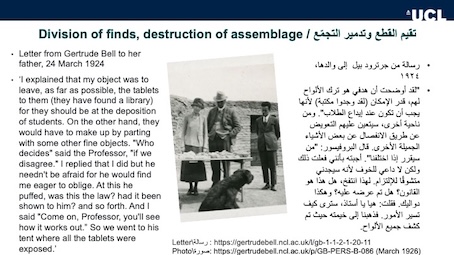

A letter [https://gertrudebell.ncl.ac.uk/l/gb-1-1-2-1-20-11] from the Honorary Director of Antiquities, Gertrude Bell PGP , to her father in 1926, describes how she and Professor Langdon divided the finds from Kish (Figure 3). Bell decided that all the cuneiform tablets should go to Oxford, which had been her university, and that the brand new Iraq Museum, which was essentially hers too, should obtain some nice archaeological artefacts instead. But as the letter makes clear, she was keen to make sure that, in this case too, Oxford would get the best deal.

The dispersed written record of Kish

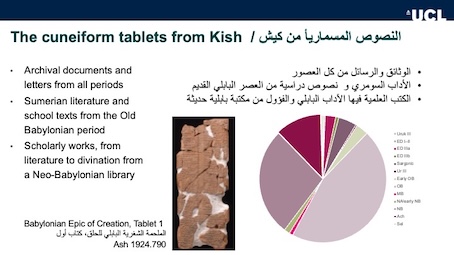

In total about 3000 tablets from Kish have left Iraq (Figure 4). They include administrative documents, legal records and letters from all periods, unique works of Old Babylonian Sumerian literature, and some of the most important exemplars of Standard Babylonian scholarship, including the first chapter of the Epic of Creation. Most have been published in some form or another, almost all in English or French, but no-one has ever attempted to write a comprehensive history with them.

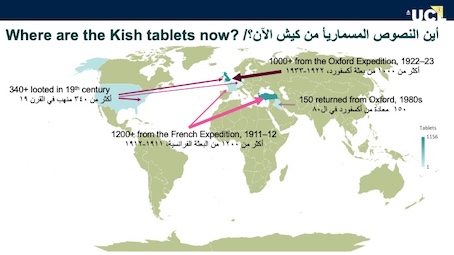

However, as Figure 5 shows, the loss of cuneiform tablets from Kish began much earlier than the Mandate period.

According to data collected from the Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative's database — which is necessarily messy and incomplete — at least 340 tablets were dug from the site in the early 20th century and sold to North American and western European collections.

The French mission of 1912 unearthed around 1200 more, most of which went to the Ottoman archaeological museum in Istanbul. At least these were systematically catalogued and published, albeit in preliminary form, in the early 1920s (Genouillac 1924-25).

The Oxford-Field Museum Expedition found double that number, and took them to Oxford. The Ashmolean Museum returned a small portion of them to the Iraq Museum in the early 1980s. But the returned tablets are all fragments of elementary scribal school exercises, and were probably considered the least interesting historical material by the curators in Oxford. The Ashmolean Museum has never systematic published its Kish tablets, though over the years most have appeared in the series Oxford Editions of Cuneiform Texts.

Recovering the lost archaeological knowledge of Kish

Over the past half-century, there have been several attempts to recover the OFME's lost archaeological knowledge of Kish. In the 1970s, MacGuire Gibson PGP in Chicago and Roger Moorey PGP in Oxford tried to piece together the archaeological evidence, and more recently Federico Zaina in Italy focused on third-millennium Kish, but none of them engaged much with the tablets (Zaina 2015; 2020).

Then in the early 2000s, the Field Museum and Ashmolean Museum collaborated on an online database of objects from the OFME [/kish/fieldmus/index.html], a decade before the similar Ur Online project. But that database disappeared from the internet about a decade ago (and we have resurrected it here). More recently, the same project published an open-access book on Kish, which is all in English and barely mentions the tablets (Wilson and Bekken 2023).

Meanwhile, we at the Nahrein Network [https://nahreinnetwork.org] have been working with Oracc to create a new multilingual online corpus of the cuneiform tablets from Kish. The aim is not only to make the textual evidence from Kish more accessible, in a single place. We have also been reprogramming Oracc so that Arabic-speaking Assyriologists can create their own editions of cuneiform texts with it, from any site, and Arabic-speaking users can read translations in their own language, on small screens like phones. A new search facility helps users to find materials across the whole of Oracc.

Conclusions and prospects

As this case study on Kish exemplifies, archaeological and historical knowledge has been lost from Iraq in multiple ways. The result is a mess: how can SBAH properly look after an archaeological site, and make it meaningful for visitors, if its employees don't have full access to the knowledge that international researchers have produced about it?

So I contend that knowledge repatriation is always a good idea, both to accompany the return of archaeological and textual artefacts and in contexts where it's not practical or appropriate to repatriate artefacts.

However, as the case of Kish shows, it's not always simple to do this. Some knowledge has been lost forever, though bad archaeological practice, and will never be recovered. Old technologies fail, like the 20-year-old Kish database, if money and resources are not invested in maintaining them.

Even surviving materials are rarely in Arabic. All Iraqi heritage experts can recall cases where they've been presented with data in unusable formats, or books in very technical English or German that are hard to read. They rarely get a say in what it is that they need.

Ultimately, I hope that we can all work to the same goal, of re-centring Iraqi expertise in the creation of new knowledge about this wonderful county's ancient past. That's the Nahrein Network's ultimate aim, but we can't do it alone. We need to change the minds, and priorities and practices, of the leaders and funders of as many international projects as possible. That will take time, and a lot of patience and diplomacy. I also hope that Iraqi experts will feel increasingle able to articulate their priorities for knowledge repatriation, both for their own work and for the country as a whole. And I hope that together we can make a positive difference.

20 Oct 2025

Eleanor Robson

Eleanor Robson, 'Knowledge repatriation and the written heritage of ancient Iraq', The Forgotten City of Kish • مدينة كيش المنسية, The Kish Project, 2025 [http://oracc.org/Knowledgerepatriation/]