The Ištar Gate (Ištar-sākipat-tēbîša)

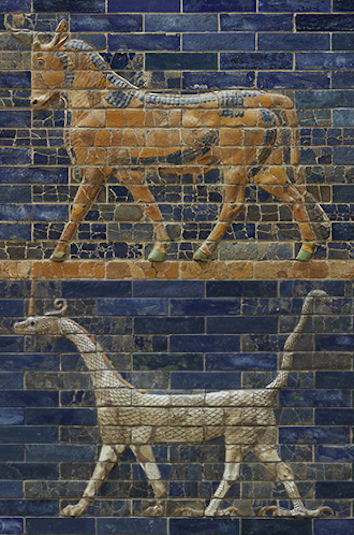

Babylon's inner city walls had eight gates, four on each side of the Arahtu River, an arm of the Euphrates that divided the city in two. The entrance dedicated to the goddess Ištar, which was located in the north wall of East Babylon, was the city's largest, grandest, and most important entrance, at least in the Neo-Babylonian Period (625–539 BC), when the city transformed into an imperial capital that was an "object of wonder" according to some Babylonian kings. The Ištar Gate, which is undoubtedly the best-known and most-famous ancient Mesopotamian gateway, was remodeled by Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 604–562 BC) as a monumental and ornately-decorated double gate. This majestic blue-glazed-brick entryway, together with its numerous bas reliefs of bulls (rīmu) and mušhuššu-dragons, is now the iconic symbol of Babylon, with modern reconstructions of it in Vorderasiatisches Museum in Berlin, as well as at Babylon itself. Moreover, it is the only gate of Babylon to be identified with absolute certainty by means of an in-situ Akkadian text; that inscription of Nebuchadnezzar II is written on a large stone block.

Reconstructed Ištar Gate in the Vorderasiatisches Museum (Berlin). Photo credit: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Vorderasiatisches Museum / Olaf M. Teßmer CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Names and Spellings

This entranceway into the Ka-dingirra district of East Babylon is referred to in cuneiform sources by its everyday/common name, the "Ištar Gate" (Akkadian Abul-Ištar), as well as by its Akkadian ceremonial name, Ištar-sākipat-tēbîša, which means "Ištar Overthrows Its Assailant," a name that reflects the war-like character of Ištar. Due to its location and importance during the New Year's festival at Babylon, the Ištar Gate was given the epithet the "Entrance of Kingship" (Akkadian nēreb šarrūti).

- Written Forms: KÁ.GAL-d15; KÁ.GAL-diš-tar; d15-sa-ki-pat-te-bi-šú; dINANNA-sa-ki-pat-te-e-bi-šú; diš-tar-sa-ki-pa-at-te-e-bi-ša; diš-tár-sa-ki-pa-at-te-e-bi-ša; diš₈-tár-sa-ki-pa-at-te-e-bi-ša.

Known Builders

- Neo-Babylonian (ca. 625–539 BC)

- Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 604–562 BC)

Building History

Although the Ištar Gate is not attested archaeologically before the Neo-Babylonian Period, the earliest, presently-attested reference to an Ištar Gate at Babylon comes from an economic document dating to the reign of Samsu-ditāna (r. 1625–1595 BC), the last king of the First Dynasty of Babylon. However, it is unlikely that Old Babylonian (ca. 1900–1600 BC) references refer to the Ištar Gate that is mentioned in royal inscriptions of the Neo-Babylonian Period, as well as in Tablet IV of the scholarly compendium Tintir = Babylon, since the plan of Babylon's inner city walls in the Old Babylonian Period (ca. 1900–1600 BC) was oval and encompassed a significantly smaller city than the later rectangular-shaped Imgur-Enlil. Although it is unknown exactly when Imgur-Enlil and its eight gates were first constructed, Imgur-Enlil and its Ištar Gate certainly existed by the late Kassite Period (ca. 1400–1000 BC).

At present, Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 604–562 BC), the son and immediate successor of Nabopolassar (r. 625–605 BC), the founder of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, is the only certainly-attested builder of the Ištar Gate. The best contemporary description of that king's rebuilding and expansion of Babylon's most important entrance is recorded in the so-called "East India House Inscription," which is written on several large stone tablets. The relevant passage (v 54–vi 21) reads:

As stated in his inscriptions, and confirmed from the archaeological record, Nebuchadnezzar had to rebuild Ištar-sākipat-tēbîša a few times during his forty-three-year reign because he had raised the level of the Processional Way that passed through it on several occasions. With each successive rebuilding, the Ištar Gate became more and more lavishly decorated. In its final form, that magnificent entranceway had a façade of blue-glazed baked bricks with rows of bulls and dragons in bas-relief.

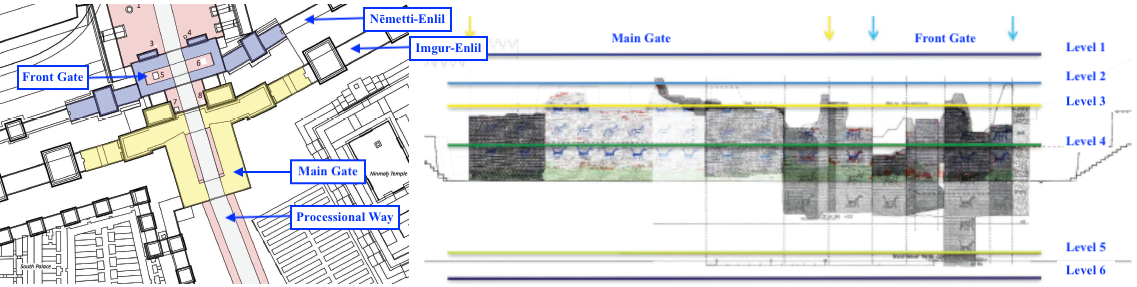

Ištar Gate in the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II with its front gate (blue) and main gate (yellow) connecting to the walls Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil (left); drawing of the eastern façade of the west wall of the Ištar Gate showing the different street levels and building phases of the gate complex in the Neo-Babylonian Period (right). Image adapted and annotated by Jamie Novotny from O. Pedersén, Babylon: The Great City, figs. 2.28–29.

Archaeological Remains

Remains of the earlier building phases of the Ištar Gate built by Nebuchadnezzar II as presently-visible at the site of Babylon.

The substantial archaeological remains of the Ištar Gate were first examined during Robert Koldewey's excavations at Babylon in 1902. In 1938, Iraqi archaeologists exposed the southern larger gate room of this monumental gate complex. Further excavations were carried out by the Iraqis in the late 1970s and in the 1980s. Unlike the other three excavated gates of the inner city of Babylon (the Uraš, Zababa, and Marduk Gates), the Ištar Gate is the only entranceway that was constructed with baked brick and had an ornate, blazed-brick façade; prior to the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II, that entrance to the city had also been constructed of mudbrick.

In the Neo-Babylonian Period, this 50-m-long architectural complex consisted of a main gate (measuring 33×22 m), which adjoined the inner city wall Imgur-Enlil, and a smaller front gate (measuring 13×28 m), which connected to the outer city wall Nēmetti-Enlil. The Processional Way that passed through Ištar-sākipat-tēbîša was paved with limestone and breccia. Four different street levels are attested, all from the reign of Nebuchadnezzar. These correspond to the successive raising of the Processional Way by that king, which at least one royal inscription recorded in detail:

These infills correspond respectively to street Levels 5, 4 and 1. The presently-best-attested street level, Level 3, however, does not have an equivalent mentioned in the afore-cited Nebuchadnezzar inscription. With each rebuilding, the gate's decoration became more and more ornate. When originally reconstructed, the façade of the Ištar Gate had reliefs of bulls and mušhuššu-dragons in plain, unglazed baked bricks (the gate associated with street levels 5, 4, and 3; assumed for level 6). Later, the façade was decorated with blue-glazed bricks, however, the rows of animals were not in relief; the building phase corresponds to street level 2. In the final Nebuchadnezzar-period rebuilding, which is known from its reconstruction in the Vorderasiatisches Museum in Berlin, the blue-glazed baked-brick façade was decorated with rows of bulls and mušhuššu-dragons in bas-relief; these remains rose above street level 1. The proposed heights of the walls of the front and main gates are 14–15 m and 18–20 m respectively. An estimated 5,700,000 baked bricks were used to build this 63,000-m2 gate complex.

Further Reading

- Abdul-Razzak, W. 1979. "Ishtar gate and its inner wall," Sumer 35, pp. 112–117.

- Abdul-Razzak, W. 1985. "Ishtar gate and the inner wall," Sumer 41 pp. 19 and 22 [English Section] and pp. 34–35 [Arabic section].

- George, A. G. 1992. Babylonian Topographical Texts (Orientalia Lovaniesia Analecta 40), Leuven, pp. 13–29, 66–67, and 339–341.

- Gries, H. 2022. Das Ischtar-Tor aus Babylon. Vom Fragment zum Monument, Berlin.

- Koldewey, R. 1970. Das Ischtar-Tor in Babylon: nach den Ausgrabungen durch die Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft (Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 32), Osnabrück (Reprint of the 1918 edition).

- Koldewey, R. 1990. Das wieder erstehende Babylon, fifth edition (edited by B. Hrouda), Munich, pp. 43–63.

- Marzahn, J. 1992. Das Ištar-Tor von Babylon. Die Prozessionsstraße. Das babylonische Neujahrsfest, Mainz, pp. 17–31.

- Pedersén, O. 2018. "The Ishtar Gate Area in Babylon. From Old Documents to New Interpretation in a Digital Model," Zeitschrift für Orient-Archäologie 11, pp. 160–178.

- Pedersén, O. 2021. Babylon: The Great City, Münster, pp. 71–80.

- Pongratz-Leisten, B. 2022. "The Ishtar Gate. A sensescape of divine agency," in K. Neumann and A. Thomason (eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Senses in the Ancient Near East, New York, pp. 320–343.

Banner image: plan of the Ištar Gate during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II (left); satellite image of East Babylon (center); digital reconstruction of the Ištar Gate in the Neo-Babylonian Period (right). Left and right images adapted from O. Pedersén, Babylon: The Great City, figs. 2.28 and 2.32.

Frauke Weiershäuser & Jamie Novotny

Frauke Weiershäuser & Jamie Novotny, 'The Ištar Gate (Ištar-sākipat-tēbîša)', Babylonian Temples and Monumental Architecture online (BTMAo), The BTMAo Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, [http://oracc.org/btmao/Babylon/WallsandGates/InnerCityWalls/IshtarGate/]