Outer city wall of Babylon

To provide greater protection for Babylon, in particular its principal temple Esagil (which is dedicated to the city's divine patron Marduk), Nabopolassar (r. 625–605 BC), the founder of the Neo-Babylonian Empire who brought an end to the Assyrian Empire, started planning and constructing an outer wall around the eastern side of Babylon. This brick wall, together with its protective quay wall and a wide moat, remained largely unfinished at the time of Nabopolassar's death in 605 BC. Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 604–562 BC), his son and immediate successor, finished the job, is clear not only from several Akkadian inscriptions, but also from its still-visible remains. Only a small, 800 m stretch, of this new, 7.5-m-long eastern outer wall was scientifically explored by the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft (DOG) and Königliche Museen Berlin (KMB) in 1899–1917 under the direction of Robert Koldewey. None of its five gates has been archaeologically attested.

Names and Spellings

According to a text referred to as the "Measurements of the City Walls of Babylon C," a text that might have been drawn up as an aide-memoire for Nebuchadnezzar, the names of the gates of this wall were (from north to south) the Šūhi Canal Gate (Akkadian Abullu ša Nār-Šūhi), the Madānu Canal Gate (Akkadian Abullu ša Nār-Madānu), the Giššu Gate (Akkadian Abul-Giššu), the Sun of the Gods Gate (Akkadian Abul-Šamaš-ilī ), and the Seashore Gate (Akkadian Abul-šapat-tâmtum).

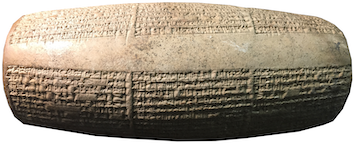

BM 091142, a three-column clay cylinder with an Akkadian inscription of the Neo-Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II recording his construction of the new outer wall at Babylon. Photo credit: Jamie Novotny.

Known Builders

- Neo-Babylonian (ca. 625–539 BC)

- Nabopolassar (r. 625–605 BC)

- Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 604–562 BC)

Building History

According to an Akkadian inscription written on several clay cylinders, Nebuchadnezzar II records that his father Nabopolassar started construction on a new wall, one that would surround and provide protection to the most important buildings in Babylon, at least those in the eastern half of the city. The relevant passage of that text reads:

In 605 BC, at the time of Nabopolassar's death, work on that wall was far from complete, according to that same text. The task of finishing the newly-started wall, which was being built to provide additional protection, fell to his son and successor Nebuchadnezzar. It is clear from several texts, as well as from its still-visible remains, that Nebuchadnezzar successfully completed the new outer wall, together with its gates. One inscription, which is also written on clay cylinders, records the following:

To provide even greater protection for his capital, Nebuchadnezzar also had a new palace (the so-called "Summer Palace") built at the northernmost point of the wall, near where it met the Arahtu River (the branch of the Euphrates River that ran through Babylon). As with the inner city walls Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil, Nebuchadnezzar had a wide, water-filled moat (Akkadian hirītu) dug outside the new city wall, which nearly doubled Babylon's size (from 4.5 km2 to 9.5 km2).

Despite the added protection, Babylon was still captured in 539 BC, bringing native rule of Babylon to an end. On the 16th of Tašritu (VII; = October 12th 539 BC), Ugbaru, the governor of Gutium, an important ally of the Persian king Cyrus, together with (part of) the Persian army, took Babylon, allegedly without a fight.

Archaeological Remains

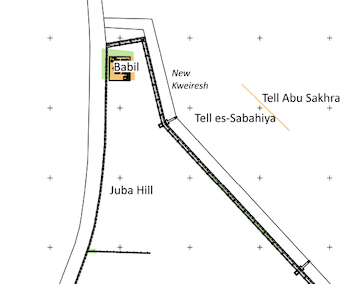

Annotated plan of Babylon showing the sections of the outer wall excavated by the Germans (green). Cropped from O. Pedersén, Babylon: The Great City, p. 15 fig. 1.4.

Traces of the eastern outer wall are still visible to this day. However, only a small portion of this 4,000–cubit-long wall (ca. 7,250 m) that protected the eastern half of Babylon and doubled that city's size has been explored. During the German excavations of Babylon under the direction of Robert Koldewey in 1899–1917, only 800 m of that wall was investigated. None of the five gates named in the "Measurements of the City Walls of Babylon C" have been positively identified.

The new outer wall consisted of a 7-m-wide unbaked mudbrick wall, a 7.8-m-wide baked-brick quay wall, a 3.3-meter-wide quay, and a wide moat. Although the "Measurements of the City Walls of Babylon C" records that the wall had 120 towers, it might have had more, perhaps somewhere between 135 and 150 large and small towers. Because little of the wall has been excavated, the actual number of towers remains unknown. The proposed maximum height of the wall is 13 m. Moreover, it has recently been estimated that the eastern outer wall, together with its quay wall, was built from as many as 96,600,000 mudbricks and 117,700,000 baked bricks.

Further Reading

- George, A.R. 1992. Babylonian Topographical Texts (Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 40), Leuven, pp. 137–141.

- Koldewey, R. 19905. Das wieder erstehende Babylon, fifth edition (edited by B. Hrouda), Munich, pp. 15–24.

- Pedersén, O. 2021. Babylon: The Great City, Münster, pp. 44, 53, 57–60 and 88.

- Wetzel, F. 1930. Die Stadtmauern von Babylon (Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichung der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 48), Leipzig, pp. 68–74 and figs. 58–60 and 80.

Banner image: map of Babylon and its surroundings prepared by William Selby in the late 1850s showing traces of the eastern outer wall of Babylon (left); map of Babylon, showing the city walls during the latter years of the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II (middle); and satellite image of Babylon still showing traces of the new wall built during the Neo-Babylonian Empire. Image created by Jamie Novotny from W.B. Selby, William and W. Collingwood, Plan of the supposed ruins of Babylon; and O. Pedersén, Babylon: The Great City, p. 41 fig. 2.1.

Jamie Novotny

Jamie Novotny, 'Outer city wall of Babylon', Babylonian Temples and Monumental Architecture online (BTMAo), The BTMAo Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, [http://oracc.org/btmao/Babylon/WallsandGates/OuterCityWall/]