Clay Cylinders (Nabopolassar [Babylon and Sippar] and Nebuchadnezzar II [only from Babylon])

Clay Cylinders (Nabopolassar [Babylon and Sippar] and Nebuchadnezzar II [only from Babylon])

Surviving Neo-Babylonian royal inscriptions are overwhelmingly written on clay cylinders. Nearly all kings of the Neo-Babylonian Empire have left inscribed cylinders.[[108]] These texts can be rather short, requiring just one column, but they can also be long and elaborate and can be written out in two, three, or four columns. Two- and three-column cylinders are the most common, while four-column cylinders were not regularly used. The shortest cylinder inscriptions in this volume are Npl. 2 (C11/B) and Nbk. 17 (C11), both comprising just fourteen lines of text in a single column.[[109]] The longest complete text included here is Nbk. 32 (C36), a 1,433-word inscription that is written in 188 lines, spread over three columns.[[110]] That text is significantly longer than Nbk. 27 (C41), which has 415 words written in 176 lines of text, over four columns; the script of this text is much larger than that of Nbk. 32 (C36). The shape of these objects varies from true cylinders to barrels and asymmetrical bullets; the most common form is the barrel. Cylinders can be solid or hollow. Some cylinder inscriptions are known today from only one exemplar, but for others more than a dozen exemplars have come down to us.[[111]] Even though shape and number of columns differ from one inscription to another, these parameters and the text layout usually stay stable for the different exemplars of a specific composition. Within the individual exemplars of one inscription, several minor variants can be detected (orthographical variants, scribal errors, omissions, additions, or other textual variations), which make every exemplar of a given inscription, as far as we are aware, unique.

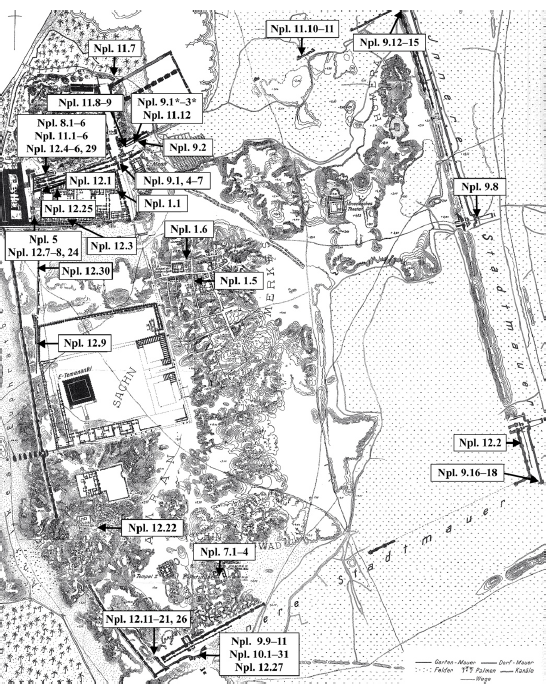

Figure 5. A plan of Babylon showing the general find spots of bricks and clay cylinders with inscriptions of Nabopolassar. Adapted from Koldewey, WEB5 fig. 256.

Cylinder inscriptions mainly provide us with information on building projects. Since these reports of construction are, just like their Assyrian counterparts, more concerned with royal ideology than historical reality, it is often hard to know if a certain building project was a complete rebuilding, a major repair, a minor repair, or regular upkeep; that is, it is unclear whether the king worked on the entire structure or just a (small) portion of it. Moreover, it is difficult to determine the (exact) dating of individual inscriptions since all descriptions of construction describe the work as if every step of building had already been completed. If an inscription with these contents is found in situ, in the building's foundations or brick structure, it is clear that the described building activities had only just started at the time the inscribed object was deposited. Given the general lack of find spots within a structure and the fact that Neo-Babylonian cylinders are not dated by the scribes who inscribed them, it is not easy to assign dates of composition within a king's reign. Dating Neo-Babylonian royal inscriptions, therefore, is far more complicated than dating the late Neo-Assyrian ones, since those texts include (long and dateable) reports about military campaigns, as well as scribal notations indicating when the objects were inscribed. Although Nabopolassar and Nebuchadnezzar were both very active military leaders, at least according to the Babylonian Chronicles (see the Chronicles section below), Neo-Babylonian inscriptions only rarely refer or allude to their successes on the battlefield; furthermore, they do not even mention the names of their enemies; this is unlike the Assyrians, who described their military successes in great detail and referred to foreign kings by name.[[112]]

108 No inscriptions are attested for Lâbâši-Marduk, a child king who ruled for only about two months. For Amēl-Marduk, Nebuchadnezzar's son and immediate successor and a man who ruled for less than two years, only one brick inscription, a single paving stone text, and four inscribed vessels are known. For editions of these short texts, see Weiershäuser and Novotny, RINBE 2 pp. 29–34.

109 Respectively, those inscriptions have forty-six and approximately fifty-four words. Other short texts include Npl. 1 (49 words) and Nbk. 29 (51 words). Note that it is unclear if Nbk. 17 (C11), the smallest known Neo-Babylonian cylinder — with a length of 6.7 cm and a diameter of 2.4 cm — should be classified as a royal inscription or a school exercise text.

110 Nbk. 36 (C031), which had a text that more or less duplicated verbatim Nbk. 2 (East India House), would have been the longest inscription of Nebuchadnezzar II written on clay. That inscription, like its stone tablet counterpart, would have had approximately 1,592 words. The largest completely-preserved known cylinder of this king (length: 26 cm; diameter: 17 cm) comes from Kish, and not Babylon. Text C38 (Da Riva GMTR 4, p. 121) , which has 1,364 words written in three columns, will be published in RINBE 1/2.

111 In the present volume, the inscription of Nebuchadnezzar written on cylinders that has the largest number of exemplars is Nbk. 29 (C21), a text commemorating that king's work on Emaḫ, the temple of the goddess Ninmaḫ at Babylon. At present, thirty exemplars of that inscription are known, but many are modern casts, not original Neo-Babylonian cylinders. The C23 and C32 texts, which will be included in RINBE 1/2, both have over thirty known exemplars. Note that the now-famous "Eḫulḫul Cylinder Inscription" of Nabonidus (Weiershäuser and Novotny, RINBE 2 pp. 140–151 Nbn. 28) has more than fifty known exemplars.

112 The only exception is Nabopolassar naming the Assyrians as enemies; Sîn-šarra-iškun, the king of Assyria and Nabopolassar's chief rival between 626 and 612, is never referred to by name. See Npl. 3 (C32) i 28–ii 5, Npl. 5 (VA Bab 636) lines 5´–9´, and Npl. 7 (C12) lines 17–21.

Jamie Novotny & Frauke Weiershäuser

Jamie Novotny & Frauke Weiershäuser, ' Clay Cylinders (Nabopolassar [Babylon and Sippar] and Nebuchadnezzar II [only from Babylon]) ', RIBo, Babylon 7: The Inscriptions of the Neo-Babylonian Dynasty, The RIBo Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, 2024 [/ribo/babylon7/RINBE11Introduction/SurveyoftheInscribedObjects/ClayCylindersNabopolassarandNebuchadnezzarII/]