The Ziggurat of Zababa on Tell Uhaimir

Tell Uhaimir, the "little red tell", is easily identifiable by its colour. Today, it can still be seen from the road, rising above the archaeological site of Kish. This mound is artificial: the accumulated debris hides a ziggurat tower dedicated to Zababa, god of war. In ancient times, this ziggurat must have been visible from far away, standing over the western portion of the city. It was a symbol of Kish's power, and of its god.

The reddish colour of this tell is probably due to the architecture of the ziggurat and to the material it is made of. In Iraq, earthen buildings were made with mudbricks, separating layers with reed and matting. To protect the integrity of these structures, water drainage and ventilation were also part of the architecture. At Tell Uhaimir, it seems that the air and damp circulated through the brickwork in such a way that they created a slow internal combustion. This fired the bricks, so that over time, they turned red (Moorey 1978: 97).

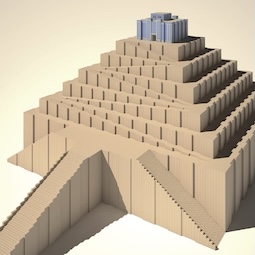

[/kish/images/ziggurat-babylon-large.jpg]

[/kish/images/ziggurat-babylon-large.jpg]Hypothetical Reconstruction of the Ziggurat of Babylon Source: Orient Cunéiforme [https://archeologie.culture.gouv.fr/orient-cuneiforme/en/architecture-ziggurat], copyright Montero Fenollós 2013.

The modern word "ziggurat" comes from the Akkadian ziqquratu (in Sumerian u6-nir), meaning temple tower. These towers were built by constructing one flat terrace on top of the other, each made gradually smaller. Then, at the very top, a temple was erected where priests celebrated daily rituals and yearly ceremonies. To access the summit, ancient builders built ramps or monumental staircases along the edge of the tower. Some ziggurats only had a staircase, like the ziggurat of Ur, while others had ramps which went from one terrace to the next. Spiritually, a ziggurat tower symbolised the link between gods and humans, between sky and earth. On a practical level, raising a temple far above ground level avoided floods and created a highly visible landmark in the flat plain (Anthonioz 2009: 70).

History of excavation

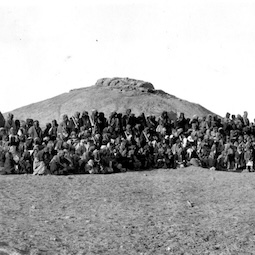

[/kish/images/ofme-staff-ziggurat-large.jpg]

[/kish/images/ofme-staff-ziggurat-large.jpg]"Group of laborers and staff, Prof. Langdon, Mr. Mackay, and Col. Lane" in front of the ziggurat of Zababa, 1920s. Source: Field Museum OFME Photo Album 140, p. 17 (Neg. No. 261, undated)

[/kish/images/basket-boys-large.jpg]

[/kish/images/basket-boys-large.jpg]"Basket boys at Kish", 1920s. Source: Field Museum OFME Photo Album 140, p. 49 (Neg. No. 502, undated)

[/kish/images/workman1-large.jpg]

[/kish/images/workman1-large.jpg]"Workman", 1920s. Source: Field Museum OFME Photo Album 140, p. 42 (Neg. No. 52785, undated)

[/kish/images/workman2-large.jpg]

[/kish/images/workman2-large.jpg]"Workman", 1920s. Source: Field Museum OFME Photo Album 140, p. 43 (Neg. No. 52509, undated)

The ziggurat of Zababa was excavated three times by foreign missions: in October 1852 by Jules Oppert, in 1912 by Henri de Genouillac, and then from 1923 by Ernest Mackay for the OFME. Unfortunately, we know little about what these excavators found because they did not publish full reports. When de Genouillac worked here, the ziggurat stood at a height of about 19.5 metres (Moorey 1978: 22). Based on data from other ziggurats in Iraq, the base of the temple tower would have been a square or rectangle, with 3-7 terraces rising of it (Anthonioz 2009: 74).

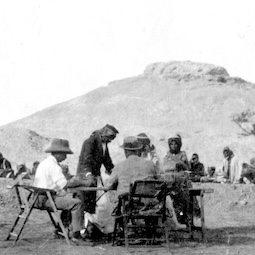

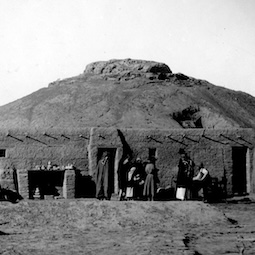

Luckily, a few photographs of the OFME's work between 1923 and 1933 survive. These are precious as they feature many of the men and children who came from Kish and its surrounding areas to lead this work. Their names were not written down, but perhaps you will recognise someone you know?

[/kish/images/paying-laborers-large.jpg]

[/kish/images/paying-laborers-large.jpg]"Paying the laborers at the camp. Stage tower of the war god Ilbaba [= Zababa] in the background", 1920s. Source: Field Museum OFME Photo Album 140 (Neg. No. 42917, undated)

[/kish/images/camp-large.jpg]

[/kish/images/camp-large.jpg]"Camp in front of the stage tower of the god Ilbaba [= Zababa]", 1920s. Source: Field Museum OFME Photo Album 140 p. 17 (Neg. No. 426, undated)

The ziggurat in Babylonian times

Because archaeologists do not have enough data, they cannot tell when the ziggurat was first built (Gibson 1972: 20-27). But clues about building and restoration work can be found in cuneiform sources. We know for example that this ziggurat was named in Sumerian E-anur-kitush-mah, "the house of the base of heaven, lofty abode" (George 1993: 52), and the temple at the top was the Edubba, "the tablet house" (Dalley 2023: 31). Inside the Edubba, the cella or inner chamber was called the E-mete-ursag, "House befitting the champion" (George 1993: 50; Frayne 2008: 49). This is where the gods' statues and sacred objects were kept.

King Sumu-la-El of the First Dynasty of Babylon (1880-1845 BC) spoke of building (or rebuilding) the E-mete-ursag shrine (Dalley 2023: 31). This shrine was later restored by Hammurabi (1792-1750), who also declared he built the ziggurat (Dalley 2023: 38). Hammurabi's son Samsu-iluna (1749-1712 BC) also looked after the ziggurat (Frayne 1990: 383-384). A tablet which records Samsu-iluna's renovation work was discovered by Mackay by the ziggurat. The tablet is in the Ashmolean Museum, in Oxford, UK, and says:

"Samsu-iluna, mighty king, king of Babylon, king of Kish, king of the four quarters, renovated the ziggurat, the lofty residence of the god Zababa and goddess Innana in Kish. He raised its head high as heaven"

A mystery about the Edubba of Zababa has yet to be elucidated: cuneiform texts indicate that this temple was in use at least until the early Hellenistic period (323-30 BC) but archaeologists have found no evidence of activity there during this period (Dalley 2023: 46).

The design and setting of the ziggurat

Did the ziggurat of Kish have a staircase like the ziggurat of Ur? So far, no evidence of a ramp or a staircase have been discovered. The ziggurat was not a lonely building. It was part of the city's religious complex, surrounded by other temples. A cuneiform tablet lists several temples at Tell Uhaimir (George 1993:52). So the summit could have been reached by walking there from the roof of an adjacent building (Moorey 1978: 26 fn 43). Another arrangement could have been a ramp set around the four sides of the ziggurat.

When de Genouillac and his team worked on the ziggurat in 1912, they reported that at the very top, on the rectangular platform, levels of reeds and matting had turned into white powder. If you can climb on top of the ziggurat today, you will still be able to see remains of these white powdery layers.

From the top of the ziggurat, de Genouillac also noticed the remains of buildings all around it. West of the ziggurat, in houses dated to the Old Babylonian period, he and later the OFME discovered hundreds of cuneiform texts there, some literary texts, other school exercises, suggesting that this was where the priests lived and educated their children (Dalley 2023: 36).

04 Jul 2025

Nadia Aït Saïd-Ghanem

Nadia Aït Saïd-Ghanem, 'The Ziggurat of Zababa on Tell Uhaimir', The Forgotten City of Kish • مدينة كيش المنسية, The Kish Project, 2025 [http://oracc.org/MoundsofKish/TellUhaimir/ZigguratofZababa/]