Early investigations (1816–1909)

How did Kish become an archaeological site? In the early nineteenth century, there was no such thing yet as archaeology, and nobody had been able to read cuneiform script for nearly two thousand years. It took a lot of work, by local people and by foreign travellers, to start to understand its ancient identity, decide that it was worth investigating further, and trial different ways of doing that.

[/kish/images/porter1822-large.jpg]

[/kish/images/porter1822-large.jpg]Figure 1: "View of Hillah on the Euphrates" (Porter 1822: pl. LXXII)

Two hundred years ago, for the people living in Hillah and the surrounding area (Fig. 1) just as for visitors, what we now call Kish was just a series of low-lying hills, covered in broken scraps of pottery, which were too dry and barren to be grazed or planted. The Arabic names for some of the larger areas hint at how local inhabitants related to them: Tell al-Uhaimir, "the little red mound", was (and is) a very distinctive tall landmark, while Tell al-Khazna, "the treasury", suggests that it was a reliable source of precious objects from under the ground. Although many modern accounts of archaeological "discoveries" ignore the local expertise that informed and guided European antiquarian travellers, it is possible to read between the lines of those travellers' accounts to flesh out a more rounded picture of knowledge exchange.

Between 1811 and 1851 at least five British diplomats or explorers visited, or passed by, Uhaimir, and described it in travelogues without fully understanding what they had seen. As Roger Moorey (1978: 1) points out, at that time, educated westerners had no option but to interpret Middle Eastern antiquity through the lens of their Classical and Biblical educations. In this view, Uhaimir could only be the eastern limit of the famous city of Babylon, whose centre was some 20 km to the west, and what we now understand to be the ziggurat was a "pile" or "heap" of bricks somehow related to Babylon's eastern wall.

James Silk Buckingham's memoir, Travels in Mesopotamia, gives revealing details of the extent to which European travellers were dependent on local support, and the perils of not taking expert advice. Visiting Babylon and "Al Hheimar" in late July 1816, Buckingham relied on the British East India Company's Resident in Baghdad, James Claudius Rich, to provide three travelling companions—one European, one Kurd (who had visited Babylon before), and one of African descent—who were all employees of the residency. Rich and the Ottoman mayor of Baghdad also provided official letters to the governor and military commander of Hillah (Buckingham 1827: 240–241).

[/kish/images/buckingham1827-large.jpg]

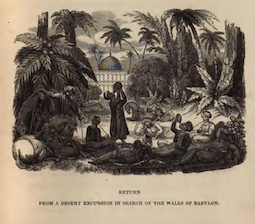

[/kish/images/buckingham1827-large.jpg]Figure 2: "Return from a desert excursion in search of the walls of Babylon" (Buckingham 1827: 294). This appears to show the travel party recuperating at the shrine of Suleiman ibn Daud, on the way back from Uhaimir to Hillah, thanks to the hospitality of the shrine's guardian.

Even so, the group set out on horseback from Hillah on a blazing summer day with insufficient water, having expected a journey of just half the distance. Half the party gave up the attempt at the shrine just west of Uhaimir. Buckingham and his unnamed "Koord horseman" companion rode on, but conditions onsite at midday were so hot, windy and dusty that they could only stay a few minutes before rejoining the others at the shrine (Buckingham 1827: 301, 349). Tired, thirsty, and probably suffering from sunstroke, they argued vociferously about the correct route back to Hillah, each going their separate ways before fortuitously regrouping at another shrine (Buckingham 1827: 352 and see Figs. 2 and 3). Here the kindly imam gave them fruit, water, and shade to sleep in, which gave them the strength to reach Hillah by sunset. Crossing the river bridge back into town (Fig. 1), they were greeted with much mirth and some insolence by the local youth, for no doubt they were a sorry sight by then (Buckingham 1827: 354–9). Without the hospitality of strangers and some dumb luck, the foolhardy enterprise could easily have turned to tragedy.

In the 1840s both British and French authorities started to support more organised antiquarian expeditions to the ancient cities of Assyria and Babylonia. Their aim was generally to discover and remove artefacts and inscriptions that could be related to the Old Testament, for study and museum display in London and Paris. Primed by the excitement of monumental stone sculpture in the palaces of ancient Nineveh and its neighbours, near Mosul, such expeditions struggled to make sense of more southerly ruins, which had been constructed without stone. It was not until the late nineteenth century that archaeological techniques developed for tracing the outlines of mudbrick walls and understanding the processes of ancient building collapse (Liverani 2016: 66).

[/kish/images/oppert1856-large.jpg]

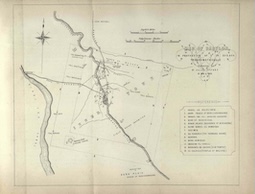

[/kish/images/oppert1856-large.jpg]Figure 3: "Map of Babylon" (Oppert 1856). Note the mounds of "Oheimir", "El-Khasneh (the treasure house)" and "Bender", marked 7, 8 and 9 in the eastern corner; the shrine of Suleiman ibn Daud (where Buckingham and his party rested in 1816) near the top; and the town of Hillah in the supposed centre of the ancient city.

Nevertheless, the urge to amass cuneiform tablets, to fuel the rapid progress of European decipherers, drove large-scale collecting "missions", such as the Expédition scientifique et artistique de Mésopotamie et de Médie of the early 1850s (Oppert 1863; Pillet 1922). So it was that a French-funded team dug for artefacts at tells Uhaimir, Khazna and Bandar in October 1852, confident they were exploring ancient Kutha, which they viewed as a district of Babylon (Fig. 3). But all of the expedition's finds sank in a shipwreck on the Tigris in 1855, while an early twentieth-century attempt to create a catalogue from surviving notes, in an attempt to salvage as much knowledge as possible from the disaster, yielded only "cryptic" hints about what had been lost (Pillet 1919; Moorey 1978: 10).

Only in the 1870s did Kish start to manifest as an ancient city in its own right. This work happened not in the field but in the museum. In 1874 the British Assyriologist George Smith correctly read the name of Kish in a inscription from a brick that another traveller had copied onsite in 1818 (Smith 1874). However, that did not mean the identitfy of the mounds was definitively settled. In 1879-80 Daoud Thoma and Hormuzd Rassam were still digging unsuccessfully for tablets for the British Museum on the mounds of Khazna, Hudhr, Ingharra, and Bandar as part of their work in greater Babylon . Even in the early twentieth century, some eminent scholars continued to argue that the location of ancient Kish was further northeast, on the Tigris (Moorey 1978: 11–12). Finally, in 1909, Louvre curator François Thureau-Dangin ingeniously combined evidence from previously published inscriptions, the topography of the site and its relationship to Babylon, and a newly acquired tablet from local excavations, to establish that Kish was Uhaimir, on an old course of the Euphrates (Thureau-Dangin 1909). In short, it took almost a century of accumulated knowledge and labour, by Iraqis and Europeans alike, for Kish to regain its ancient identity.

30 Jun 2025

Eleanor Robson

Eleanor Robson, 'Early investigations (1816–1909) ', The Forgotten City of Kish • مدينة كيش المنسية, The Kish Project, 2025 [http://oracc.org/ModernhistoryofKish/Earlyinvestigations/]