Local excavations and antiquities dealers (1912-1923)

After leaving Iraq in May 1912, de Genouillac PGP kept in regular contact with antiquities dealers in Baghdad to purchase artefacts from Kish. As before, Messayeh PGP and Samhiry PGP continued to buy collections for him, which they then shipped to Gejou PGP in Paris.

Samhiry had two tasks. First, he was to keep cases exclusively destined to de Genouillac at his home until the latter could collect them in person. For these, de Genouillac would pay Messayeh, Samhiry, or Gejou directly. Other cases were to be sent to specific clients, in particular the Louvre Museum in Paris and the Royal Museums of Art and History in Brussels. In the event of a sale, these clients would pay Gejou directly, and he would then send a share of the proceeds to the collections' owners. But these institutions did not always want the objects offered, and their refusals illustrate how Kish artefacts ended up dispersed across Europe and the USA.

A typical example is a collection of 32 tablets from Warka and 25 cylinders from a variety of sites, including Kish, sent by Gejou to the Royal Museums of Arts and History on behalf of Messayeh in 1912 [1]. When the museum refused and returned the objects, Gejou and Messayeh organised for the collection to be handed over to Rizouk Messayeh's PGP branch of the family business [2]. The correspondence between dealers and de Genouillac also shows that the number of Kish tablets they discuss is much higher than those currently identified today in collections.

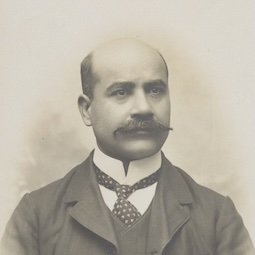

Aside from Messayeh and Samhiry, other dealers in Baghdad also heard of de Genouillac's interest in Kish artefacts and sent collections to Paris for him. George Khayat PGP , for example, sent him 474 Kish tablets in May 1912, at Gejou's home [3]. Had Khayat's letter not survived, it would be impossible to add him to the provenance chain of these objects because the cases he sent to France were not registered under his name but under two of his friends'. As he himself writes, one case of 132 Kish tablets was put under the name of David Fetto PGP (Figure 1), a dealer based in Baghdad, and a second case of 342 Kish tablets was sent under the name of David Nohmé PGP , a dealer who operated from Marseilles.

De Genouillac also bought Kish artefacts from several other dealers, sometimes sorely regretting it. He complained for example to Samhiry that the collections he had bought from the infamous Richard Cooke PGP , and Thomas Meymarian PGP (better known for selling carpets), were unsaleable: "except for texts (bricks and tablets), everything I buy from you [Samhiry], Messayeh, Cooke and Meymarian is left in my hands!!" [4]

Despite relationships that tied them to Paris, dealers did not always send their Kish collections to France. In the winter of 1912, Samhiry writes that he sent a case of "about a hundred pieces [...] mostly from Kish [...]" to J.J. Naaman PGP , a dealer based in London who specialised in trading ancient manuscripts, but who also sold cuneiform tablets on occasion [5]. Samhiry seemed especially impressed by 50 tablets from Kish, describing them as "remarkable, large, their clay entirely red". Samhiry had purposefully chosen to send them to Naaman instead of Gejou because he was unhappy with the latter at that point. He had entrusted Gejou with 90 cuneiform tablets from Sippar, Nippur, Drehem, and Kish in 1910 but in November 1912, they were still unsold [6]. But he must have known that Gejou would not be prevented from getting involved in this deal. Gejou knew Naaman well, they were cousins.

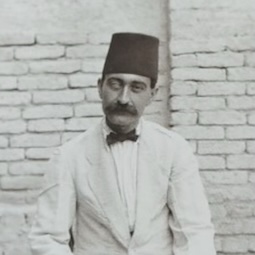

[/kish/images/seller-from-nasiriyeh.jpg]

[/kish/images/seller-from-nasiriyeh.jpg]Figure 2: "Seller from Nasiriyeh" (1922-1923). Source: Márquez Rowe 2015

After 1913, Kish artefacts stopped coming to Europe, at least through these dealers, probably because of World War One. During the war, Gejou continued to sell antiquities, but he mentioned Kish artefacts in 1914, in a list of objects he sent to the British Museum on 4 April. The list records one collection of 29 cuneiform tablets, a second of 44 tablets, and a third of 196 tablets, all labelled "from Ahemir" (Kish).

When Baghdad fell to the British in March 1917, antiquities dealers found themselves unable to export artefacts for a time. But this would not last. By 1920, these men had managed to resume their international trade. The Antiquities Law of 1924 would also help their business, when its Article 13 made the exportation of archaeological artefacts legal for permit holders. Surviving letters from the dealers make no explicit mention of Kish until 1930, when de Genouillac returned to excavate much further south, in Tello.

Notes

- Messayeh's letter to de Genouillac, 7 November 1912: "Je vous prie tout spécialement à liquider l'affaire des 32 tablettes de Ouarka [Uruk] et mes 25 cylindres toujours en suspend avec les musées de Bruxelles dont j'espère de votre amabilité avoir une bonne fin tout en vous remerciant aussi de ce chef". [Return to main text]

- Gejou's letter to de Genouillac, 12 December 1912: "Mr Messayeh est autorisé par son frère Alexandre à vous céder la tablette anzanite à votre prix de f1600. et me demande de lui verser l'argent ainsi que pour sa part du lot des 32 tablettes et de l'affaire des cylindres."; Rizouk Messayeh letter to de Genouillac, 12 December 1912 "I may leave Paris any day for other parts of Europe before going to New York and would therefore kindly request to hear from you, at your earliest possible convenience, regarding the 32 tiles and 25 cylinders now in the hands of Brussels' museum". Alexander Messayeh letter, 28 March 1913: "Bonne note a été prise que vous versez les 1600 frs contre-valeur de la pièce anzanite à Géjou ainsi que Bruxelles a refusé les 32 tablettes dont je pense que mon frère pourrait les écouler en Amérique au plus de 3000 frs a cela j'ai avisé Géjou de les remettre à mon frère." [Return to main text]

- Khayat's letter to de Genouillac, 16 May 1912 "Tablettes Je vous prie particulièrement d'avoir la bonté à examiner mes tablettes de l'Oheymir [= Kish], chez I. Gejou, dont les 132 pièces existent chez lui au nom de Mr David Fetto de Bagdad et les 342 pièces au nom de Mr David Nohmé de Marseille, quoique ces tablettes sont aux noms de mes susdits amis, mais tous m'appartiennent; si en cas que cette marchandise vous intéresse, veuillez me donner votre dernière offre directement, et en cas d'accord vous aurez l'autorisation à les posséder". [Return to main text]

- De Genouillac's letter to Messayeh, dated July, no year or day: "Je vous ai dit que sauf les textes (briques et tablettes) tout ce que je vous ai acheté à vous, à Messayeh, à Cooke et à Meymarian me reste sur les bras !!". [Return to main text]

- Samhiry's letter to Genouillac, 21 June 1912: "Après le départ de ma lettre du 17ct j'ai eu la chance d'acheter encore une collection de tablettes très importantes se composent d'une centaine de pièces et provenant de 3 endroits. Abou Nakhla, Çletehich(?) ou Djgheiman et principalement d'El-Oheimir [= Kish]. Les tablettes de ce dernier endroit sont au nombre d'une cinquantaine qui sont remarquables, grandes et de la terre tout à fait rouge et je pense les rendre au moins à fcs 30 la pièce. J'ai l'intention de les envoyer à Mr Naaman". [Return to main text]

- Samhiry's letter to de Genouillac, 29 November 1912: "Consignation chez Géjou: "Je vous remercie beaucoup d'avoir pensé à ma collection qui se trouve chez ce Monsieur depuis le commencement de 1910 et vous m'obligerez infiniment si vous voudriez bien encore vous donner la peine pour me régler cette affaire avec lui." [Return to main text]

03 Jul 2025

Nadia Aït Saïd-Ghanem

Nadia Aït Saïd-Ghanem, 'Local excavations and antiquities dealers (1912-1923) ', The Forgotten City of Kish • مدينة كيش المنسية, The Kish Project, 2025 [http://oracc.org/ModernhistoryofKish/Dealers1912-1923/]