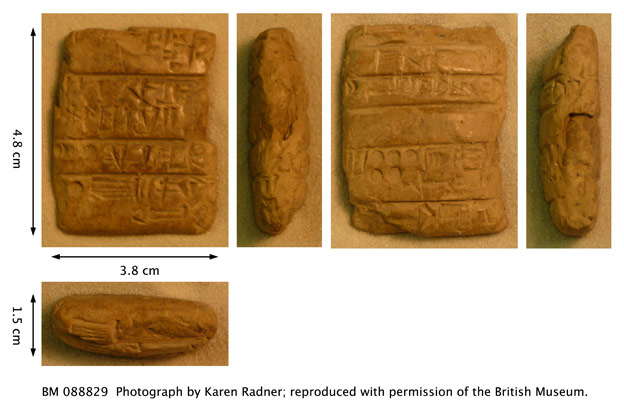

BM 088829: administrative text

BM 088829: administrative text (Old Akkadian period, c.2300 BC). Photograph by Karen Radner; reproduced with permission of the British Museum. View large image.

In the 24th century BC, king Sargon of Agade (or Akkad PGP ) would make his mark on Mesopotamia more effectively than any other man. (He is not to be confused with king Sargon of Assyria PGP , who ruled in the late 8th century BC.) This super-human figure became the stuff of legend, rising from the humblest of origins to achieve divine status. His territory – perhaps the world's first empire – was to be administered through a new bureaucratic apparatus.

The old city-states were monitored by local outposts of the Agade regime. Imperial business was to be conducted according to imperial standards. Most obvious is the elevation of Akkadian to official language of state. The cuneiform script blossomed into a beautiful calligraphic form. Even the most mundane of documents could be written with a carefully controlled hand, embellishing the signs with astonishing numbers of wedges. Occasionally a scribe would slip from the imperial script into that of a more informal local form.

As this tablet shows, the old habit of writing signs in text boxes known as 'cases' had been superseded by writing in lines of text, with signs arranged in the order in which they should be read. These features would become standard for all later versions of cuneiform.

To see more online photos, view the record for this tablet on the British Museum's research database [http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/search_the_collection_database.aspx].

Content last modified on 31 Mar 2025.

Jon Taylor

Jon Taylor, 'BM 088829: administrative text', Knowledge and Power, Higher Education Academy, 2025 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/saao/knpp/CuneiformRevealed/Tabletgallery/BM088829/]