Inscriptions of Nebuchadnezzar II from Babylon

Jump to Nebuchadnezzar II 1 Nebuchadnezzar II 2 Nebuchadnezzar II 3 Nebuchadnezzar II 4 Nebuchadnezzar II 5 Nebuchadnezzar II 6 Nebuchadnezzar II 7 Nebuchadnezzar II 8 Nebuchadnezzar II 9 Nebuchadnezzar II 10

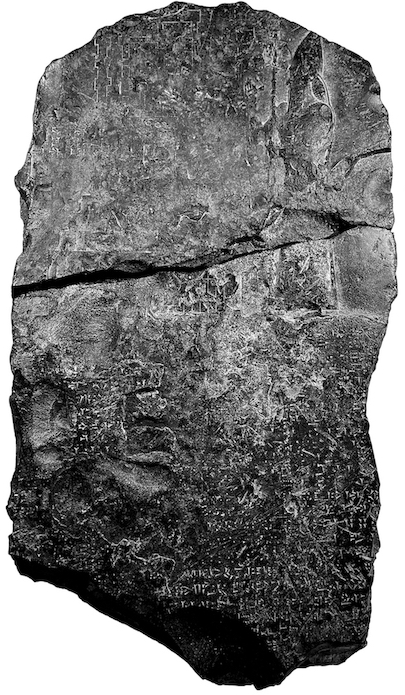

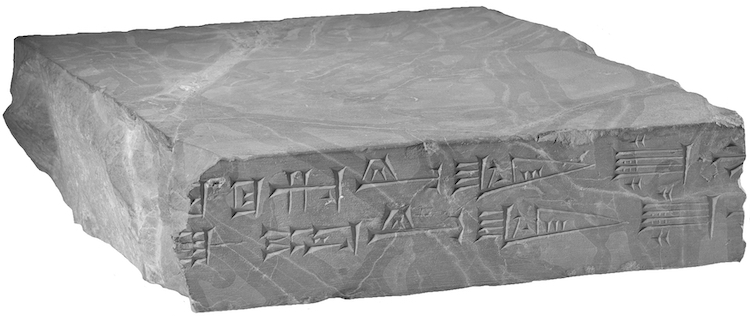

Two fragments of a polished, rounded-topped stone stele that were until recently in the Schøyen Collection (near Oslo) preserve part of an Akkadian inscription of Nebuchadnezzar II recording the restoration of Etemenanki, the ziggurat of the Marduk at Babylon, and Eurmeiminanki, the temple-tower of the god Nabû at Borsippa. The text, which is distributed across several columns and written in archaizing Neo-Babylonian script, is accompanied by a bas-relief depicting a left-facing Nebuchadnezzar standing in front of an idealized seven-tiered ziggurat, which is shown in profile and identified by a three-line epigraph as Etemenanki; this image occupies the upper two-fifths of this badly damaged monument. In addition, two ground plans of temples are engraved on the stele: The first, which is above the image of the ziggurat on the stele's front side, represented the main temple that sat atop Marduk's temple-tower at Babylon, and the second, which is on the object's upper left side, probably depicted the plan of the temple that stood on the upper tier of Eurmeiminanki at Borsippa. This monument is popularly known as the "Tower of Babel Stele"; in Assyriological literature, it is also sometimes called the "Babylon Stele."

Access Nebuchadnezzar II 1 [ /ribo/babylon7/Q005472/].

Source

| IM — (formerly MS 2063) |

Commentary

Until December 2023, the two stele fragments comprising the "Tower of Babylon Stele" (MS 2063) were in the Schøyen Collection, in the vicinity of Oslo. When it became apparent that the pieces had been discovered in the 1990s and smuggled out of Iraq illegally, Dr. M. Schøyen immediately decided to send the now-famous artifact to the Iraq Museum (Baghdad). This unconditional gift was officially received at the lraqi Embassy in Oslo on December 14, 2023. The stele has now been formally returned to the Republic of Iraq and will be exhibited in the Iraq Museum "for all Iraqi[s] and other visitors to see and study" (Schøyen, personal communication).

The authenticity of the stele has been recently called into question; see, for example, Dalley, BiOr 72 (2015) cols. 754–755; Lunde, Morgenbladet 2022/29 pp. 26–33; and Dalley, BiOr 79 (2022) cols. 428–434. The suggestion that it is a modern fake, rather than an authentic Neo-Babylonian-period monument, has largely stemmed from the dubious stories surrounding its discovery in the Schøyen Collection database (which have been repeated in scholarly publications; for example, Shanks, BAR 28/5 [2002] pp. 25–34; and Van De Mieroop, AJA 107 [2003] pp. 257–275), as well as the study of the images of the king and ziggurat and the inscriptions (the main text and epigraph) from published photographs (see the Dalley references above), rather than from the original itself. In 2023, the stele was closely re-examined by R. Da Riva (October), A.R. George (May, September, and October), J. Novotny (September), and O. Pedersén (September and October). Moreover, Pedersén has written a short article providing additional credible evidence about the object's discovery in Babylon (see below for details). The discussion presented here mostly derives from in-person conversations with George and Pedersén, both in front of the stele (14–15 September, 2023) and via email, a paper of George to appear in BiOr 80 (2023), and Pedersén's forthcoming article in the journal Iraq (Iraq 85 [2023]); additional comments from Da Riva are also incorporated here. The authors would like to thank George and Pedersén for allowing them to include their findings in RINBE 1/1 prior to the publication of their own studies on the subject. The authors must also express their gratitude to M. Schøyen for allowing a firsthand examination of the stele, as well as to George for facilitating that onsite visit.

Contrary to earlier, (fabricated) reports that the broken stele was discovered in "a special hiding chamber" in 1917 by R. Koldewey — who is said in these accounts to have immediately recognized the monument's importance and to have had its fragments shipped to Germany and the United States for safekeeping — the two extant pieces of the stele were actually found in the early 1990s (see below). Moreover, the Schøyen Collection database stated that there were three, not two, stele fragments that were unearthed and subsequently photographed. These erroneous pieces of information helped fuel doubts about the credibility of the stele's purported find spot (and, later, its authenticity), principally since no record of this (important) discovery is known from the extensive field notes and numerous excavation photographs of Koldewey's excavations at Babylon (1899–1917). This unconvincing evidence led George (CUSAS 17 pp. 164–165) to tentatively suggest that the monument did not originate from Babylon, but rather from the Elamite religious capital Susa; he postulated that it had been carried there after Etemenanki had been damaged during two revolts in Babylon in 484, against the Persian king Xerxes I (r. 485–465). This was not an unreasonable suggestion since a fragment of a clay cylinder inscribed with a text commemorating Nebuchadnezzar's work on Marduk's temple-tower (Nbk. 27 [C41] ex. 2) was found at Susa. In a forthcoming article, Pedersén has presented sufficient evidence that the two stele fragments actually come from Babylon; this information was known to him before the publication of his Babylon book, but he was asked not to include that story. According to people living in the Jumjuma village, two local fishermen found two stone fragments with reliefs and cuneiform inscriptions on the Amran hill, in the trench that Koldewey's workmen had dug northwards from the large pit in the ruins of Esagil in 1900; the pieces likely fell out of one of the sides of that wide trench. Rather than reporting the discovery to the State Board of Antiquity and Heritage, the locals gave the stele fragments to Saddam's security forces, who then smuggled them out of Iraq under the pretense that the stones were just modern creations, not ancient artifacts. This information, which currently lacks corroboration from photographs and other firsthand witness accounts, has been kept a secret for a long time, notably since the proper actions had not been taken at the time. Pedersén has now been permitted to publish this story, under the condition that the people involved remain unnamed. Assuming that this new account proves true — as Pedersén rightly notes, "[t]he villagers do not have any advantage of telling the story, which on the contrary could create possible problems" — then the "Tower of Babel Stele" might have come from about 20 m north of the main Esagil temple, at an estimated elevation of +14 m or (a little) higher; see the red dot on Pedersén, Iraq 85 fig. 2. This would have been between Esagil and Etemenanki, within the main temple complex, in the Parthian stratum, just 50 m south of a Parthian house (ibid. fig. 2 blue dot) from which more than 220 fragmentary stone objects (including five damaged @i{kudurru}s) were excavated; all, or at least most, of these broken monuments, as is clear from the texts written on them, came from Esagil and date from the early Kassite Period to the Hellenistic Period. Based on this information, the stele might have been part of such a Parthian collection of monuments. Given its current state, it would not be unreasonable to assume that it might have been (accidentally) destroyed when Babylon rebelled in 484 and when Marduk's ziggurat was damaged. Compare, for example, the Darius Stele that had been erected in front of the Ištar Gate, a monument that had been intentionally targeted by the rebels; for an overview of the rebellion, see Waerzeggers, Xerxes and Babylonia pp. 1–18. Of course, this is pure speculation, but it might explain why this damaged-in-antiquity monument was not found in Esagil or Etemenanki, but rather in a later, secondary context. Of course, there are other possible explanations (see below).

The poor state of preservation of this black-stone stele (possibly dark siltstone according to N. Al-Ansari [information from Pedersén]) makes it very difficult to accurately assess some details of the monument only from photographs, even good close-up and high-resolution digital images; more details about the monument's current condition are recorded in Pedersén, Iraq 85. This is (mostly) because the monument's surfaces are badly worn, the fragments are not securely joined together (thereby making it tricky to photograph the object in a manner that does not misrepresent what is actually carved), and the cuneiform inscriptions are not deeply engraved (thus making the heads of the cuneiform wedge appear in photographs as if they have no depth or sharp edges). Examination of the images of the king and ziggurat and the inscriptions solely from available photographs and/or George's hand-drawn facsimile (CUSAS 17 pls. LVIII–LXVII) has led some scholars to believe that the stele is a modern fake (see above); note also that Novotny initially had some reservations based on published and unpublished photographs, but his doubts disappeared after studying the original. In-person studies, however, have clarified some details about the stele that had earlier given rise to doubts about the object's authenticity. Most notably, (1) the representation of the central, left-facing Nebuchadnezzar (although his name is not preserved on the object), with his right hand outside of the staff and away from his face, is executed with care and is consistent with other Neo-Babylonian-period monuments (including steles of Nabonidus from Ḫarrān [Gadd, AnSt 8 (1958) pls. II and IX–XVI] and Uruk [Lenzen, UVB 12/13 pls. 21b, 22a, and 23a]); (2) contrary to George's hand-drawn facsimile (CUSAS 17 pls. LIX and LXIV) and published photographs (ibid. pls. LVIII, LX, and LXIII), the staff is straight on both fragments (confirmed also by George and Pedersén); (3) the profile-view of the ziggurat is evenly carved and incised on both pieces and the diagonal line that leads from the bottom right corner upwards towards the top of the first tier is intentionally rendered (it is not a random scratch, as Dalley has suggested); (4) the inscription(s) are executed by someone trained in cuneiform (see below); and (5) there is no clear evidence that the upper and lower fragments were carved separately or that parts of the iconography and inscriptions were engraved around pre-existing damage. Further details will be provided by George (BiOr 80).

The representations of the profile-view of the ziggurat and the ground plan of the temple that sat atop Etemenanki in lieu of divine symbols, as well as the inclusion of epigraph(s), are unusual, but not unique, as correctly noted by George (ibid.). Compare, for example, Nabonidus' Uruk Stele (Lenzen, UVB 12/13 pls. 21b, 22a, and 23a), Gudea Statue B (Parrot, Tello pl. XIV b, d), the Sun-god Tablet of Nabû-apla-iddina (Woods, JCS 56 [2004] p. 26 fig. 1), and a kudurru of Marduk-apla-iddina II (Babylon: Wahrheit p. 237 fig. 160). For the depictions of ziggurats in Mesopotamian art, see Miglus, RLA 15/5–6 (2017) p. 329 §6. Note, however, it is not impossible that the usual symbols of the moon (Sîn), the sun (Šamaš), and the planet Venus (Ištar) might have been carved on the stele's top edge, just above the king's head. That part of the object, which also included the upper part of Nebuchadnezzar's crown, appears to have been intentionally cut off; that small piece might have been removed and sold separately from the rest of the stele. Because "the divine presence is represented by the ziggurat itself," as George has suggested, the divine symbols were not needed and their inclusion "would perhaps be redundant." As for the depiction of Etemenanki, George (BiOr 80) and Pedersén (Iraq 85) have rightly pointed out that the representation of Marduk's temple-tower need not be a true-to-life image. Furthermore, as George has already noted, an ideal ziggurat would have had seven tiers (six stories plus the main temple) and, therefore, the sculptor depicted Etemenanki as such on the stele.

Lastly, the quality of the execution of the inscription has been questioned as not being authentic Neo-Babylonian. The main inscription, when examined from the stele itself, was clearly produced by someone trained to write cuneiform on stone. Da Riva (personal communication), who recently carried out a careful paleographical study of the inscriptions, has also noted the inferior quality of the workmanship of the texts; this might have been due in part to the stone on which it was engraved, which made it difficult to deeply incise the cuneiform signs. The heads of the wedges (as mentioned above) have sharp edges; they are not rounded, as they appear in photographs. There are no more scribal mistakes in the main text than there are on other royal inscriptions. Furthermore, the erasure in col. ii, although not thoroughly carried out (as traces of the underlying signs are still visible), is intentional and might have taken place either when the monument was originally created or later, when the stele was damaged (see above for one possible scenario); Da Riva has tentatively proposed that these signs might not have been fully incised. Examination of the visible heads of the wedges on the original look intentionally placed and surely represented an authentic Nebuchadnezzar-period text. Thus, there is no reason to suspect that the erasure was a creation of a modern forger to give the impression that that part of the inscription had been removed. On the other hand, the poor execution of the text might suggest that the stele was never displayed publicly, so the object was discarded, rather than being set up in Etemenanki (or Esagil). Moreover, it is possible that the inscription itself was never finished (as suggested by Da Riva) since the carver incorrectly estimated the space needed to correctly execute the entire inscription.

Given the currently available evidence, the authors of the present-volume see no compelling reason to view the "Tower of Babel Stele" as a modern fake and, therefore, the monument is treated here as a genuine Neo-Babylonian artifact. The inscriptions are edited here following RINBE's editorial practices.

The stele, as far as it is preserved, seems to have had two texts: (1) the main inscription, which is engraved in three columns below the images of Nebuchadnezzar and the ziggurat and, perhaps also in a single column on the now-missing lower right side (see below); and (2) a three-line epigraph, which is written to the left of the temple-tower's profile-view and which identifies the structure as Etemenanki. It is clear that the main inscription did not end at the bottom of col. iii, in the lower right corner of the stele. However, it is uncertain if the stonemason wrote out the end of the text in a now-missing col. iv, which was written on the monument's lower right side, or if he decided not to complete the rest of the inscription since he knew that the object would be discarded as it was not up to the high standard of a royally commissioned monument. If the scribe had completed the text, and it is not entirely certain that he did, then that no-longer-extant passage would have included the end of the building report and the concluding formula (most likely an address to Marduk [and possibly also Nabû]).

The main text duplicates, although with significant textual and orthographic variation, Nbk. 27 (C41) i 8–18, ii 24–43, and iii 35–37; and Nbk. 23 (C35) i 38–41. The proposed restorations are generally based on those two inscriptions. The inscriptions were collated from the original by Novotny and Da Riva.

Since the main building report is concerned with the rebuilding and completion of Marduk's and Nabû's ziggurats at Babylon and Borsippa respectively, this text is very likely to have been composed earlier than the inscriptions in whose prologues reference is made to the completion of Etemenanki and Eurmeiminanki. These texts are: Nbk. 2 (East India House), 23 (C35), and 54 (B 21); the WBA and WBC inscriptions were also written after the Babylon Stele text. The chronological relationship to Nbk. 27 (C41), C212, and C041 is unclear. It is possible that the present text was written after Nbk. 27 (and the earlier texts recording work on Marduk's temple-tower), but before or around the same time as the C212 and C041 texts (both of which commemorate the construction of Nabû's ziggurat). The prologues of Nbk. 19 (C34), 31 (C33), 32 (C36), 36 (C031), C32, C37, and C38 all mention the completion of Etemenanki, but not that of Eurmeiminanki, so the precise chronological relation of the Babylon Stele to those inscriptions is unknown. Construction on Nabû's ziggurat appears to have begun later in Nebuchadnezzar's reign than the rebuilding and completion of Etemenanki; this will be discussed further in the introduction of RINBE 1/2.

Bibliography

The former Schøyen Collection MS 2063 (Nbk. 1), the so-called "Tower of Babel Stele," a fragmentarily preserved stele of Nebuchadnezzar II with an image of the king standing before Etemenanki, the temple-tower of the god Marduk at Babylon. Photo courtesy of Olof Pedersén.

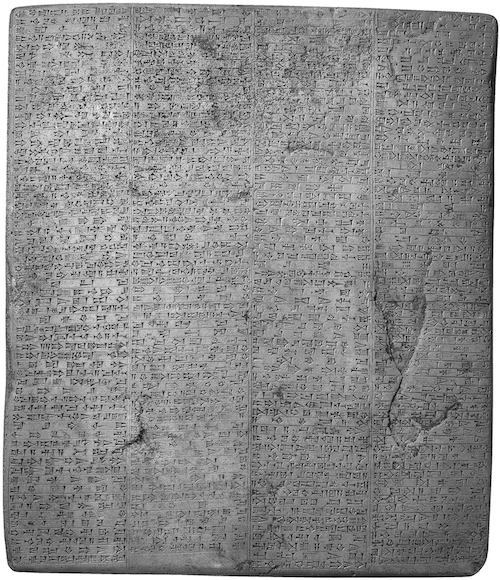

Two complete and one fragmentary limestone tablets are inscribed with a long Akkadian text of Nebuchadnezzar II recording his building activities in Babylon. The text on all three objects is engraved in archaizing Neo-Babylonian script. This inscription was composed in order to commemorate the construction of the king's new palace, the so-called "North Palace," which was built northwest of the Ištar Gate, just outside the city walls and immediately next to the processional way. Nebuchadnezzar states that he raised its superstructure as high as a mountain using baked bricks and bitumen; roofed it with a variety of wood, especially cedar imported from Mount Lebanon; installed metal-ornamented wooden doors musukkannu-wood, cedar, cypress, and ebony); decorated its parapets with blue-glazed bricks; and constructed a fortification wall using strong stones and large slabs quarried from the mountains. The work, which is said to have begun in a favorable month and on an auspicious day, took "(just) fifteen days" to complete. This, however, does not reflect historical reality since it took significantly longer to construct this extensive palatial structure; fifteen was likely chosen as half of an ideal month.

Before commemorating the construction of the (new) North Palace, the prologue of this 1,592-word-long inscription also records numerous other building activities of Nebuchadnezzar at Babylon and Borsippa. These are: (1) work on Marduk's temple Esagil, especially the roofing and decoration of the cella Eumuša; (2) the completion of the massive brick superstructures of Etemenanki, the ziggurat of Babylon, and Eurmeiminanki, the ziggurat of Borsippa; (3) construction on Nabû's temple Ezida, in particular the decoration and roofing of its cellas and one of its principal gates (Kaumuša); (4) the refurbishment of Marduk's and Nabû's ceremonial boats (Maumuša and Maidḫedu), which they used during New Year's festivals; (5) the rebuilding of numerous temples at Babylon, namely Esiskur (the akītu-house), Emaḫ (the temple of the goddess Ninḫursag/Ninmaḫ), Eniggidrukalamasuma (the temple of Nabû of the ḫarû), Ekišnugal (the temple of the god Sîn), Edikukalama (the temple of the god Šamaš), Enamḫe (the temple of the god Adad), Esabad and Eḫursagsikila (temples of the goddess Ninkarrak/Gula), and Ekitušgarza (the temple of the goddess Bēlet-Eanna); (6) the renovation of several temples at Borsippa, specifically temples for the god Mār-bīti, the goddess Gula (Egula, Etila, and Ezibatila), the god Adad, and the god Sîn (Edimana); (7) the completion of the inner city walls Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil, as well as the reinforcement of the embankment walls that ran alongside them; (8) the raising, improvement, and beautification of Babylon's processional streets, especially Ay-ibūr-šabû; (9) the reconstruction and decoration of the Ištar Gate (Ištar-sākipat-tēbîša) with a façade of blue-glazed bricks that had representations of wild bulls (and) mušḫuššu-dragon(s) fashioned on them; (10) the construction of a new outer wall that encompassed the eastern half of Babylon; the rebuilding of Borsippa's city wall (Ṭābi-supūršu); and (11) the renovation and decoration of the (old) South Palace. Before describing his work, Nebuchadnezzar refers to his military campaigns in far-off lands and remote mountains and to having received substantial tribute from those places.

The text, which ends with a prayer to the god Marduk, is generally known in scholarly literature as the "East India House Inscription," the "Stone Tablet [Inscription]," and "[Nebuchadnezzar] Stein-Tafel X."

Access the composite text [/ribo/babylon7/Q005473/] or the score [/ribo/bab7scores/Q005473/score] of Nebuchadnezzar II 2.

Sources

| (1) BM 129397 (1938-5-20,1) | (2) SCT 1982.2.8 |

| (3) BM 122119A (78-9-2,2) |

Commentary

This text, the so-called "East India House Inscription," is one of the longest-known Neo-Babylonian royal inscriptions: it is 1,592 words long. In addition to being written on (at least three) large stone tablets, this text was also written on three-column clay cylinders, but inscribed in contemporary Neo-Babylonian script, rather than in an archaizing one; see Nbk. 36 (C031) for further details. The stone tablets are all presumed to have come from the North Palace at Babylon, one of the new royal residences that Nebuchadnezzar II built for himself in his imperial capital. Of course, this cannot be proven with certainty since the "East India House Tablet" (ex. 1 [BM 129397]) was discovered before 1803 by Sir H. Jones Bridges (British Resident in Baghdad), nearly one hundred years before the R. Koldewey-led German excavations at Babylon (1899–1917); this completely intact exemplar of the inscription is named after the place where it was first exhibited: the museum in the East India House, the headquarters of the East India Company in London. The same is true of the other two exemplars: both were purchased, so their original find spots are unknown. Ex. 3 (BM 122119A) was purchased from the antiquarian J.M. Shemtob in 1878, in Babylon, and no information about the acquisition of ex. 2 (SCT 1982.2.8) has been published or made publicly available. Note that SCT 1982.2.8 was in the Arthur M. Sackler Collections and then put up for auction at Christie's in New York on the 8th of June, 2012, but the object was not sold; the present whereabouts of that damaged tablet are not known. Ex. 2 was twice reused in antiquity, once as a door socket, and so removed from the original location where Nebuchadnezzar had it deposited or displayed.

J. Novotny collated ex. 1 from high-resolution photographs, ex. 2 (SCT 1982.2.8) from the published photographs (Wallenfels, Studies Slotsky pls. 1–4), and ex. 3 from the original in the British Museum. There are also two casts of ex. 1: BM 12138, which is also housed in the British Museum, and VAG 169, which is in the Vorderasiatisches Museum (Berlin). Ex. 1, the only complete exemplar of this inscription, is generally used as the master text. A score of the inscription is presented on Oracc and the minor (orthographic) variants are given at the back of the book, in the critical apparatus.

With regard to its date of composition, the present text appears to have been one of the latest-dated presently known inscriptions of Nebuchadnezzar II, together with Nbk. 23 (C35) and the WBA and WBC inscriptions. This assessment is based largely on the building projects at Babylon and Borsippa mentioned in this inscription's very long prologue (i 1–viii 18). The very similar Nbk. 36 (C031), exemplars of which were inscribed on three-column clay cylinders, was likely written shortly before the present inscription. This assessment is principally based on the fact that that inscription has a shorter description of the rebuilding of Etemenanki (Marduk's ziggurat at Babylon) and does not mention that Nebuchadnezzar renovated Eurmeiminanki (the temple-tower of Nabû at Borsippa); see the on-page notes of Nbk. 36 (C031) for further details. The present text is earlier in date than Nbk. 23 (C35). See the commentary of that inscription for more details.

Bibliography

Reverse face of BM 129397 (Nbk. 2 ex. 1), the so-called "East India House Tablet," which is inscribed with a long Akkadian inscription recording Nebuchadnezzar II's building activities at Babylon and Borsippa, including the construction of the North Palace. © Trustees of the British Museum.

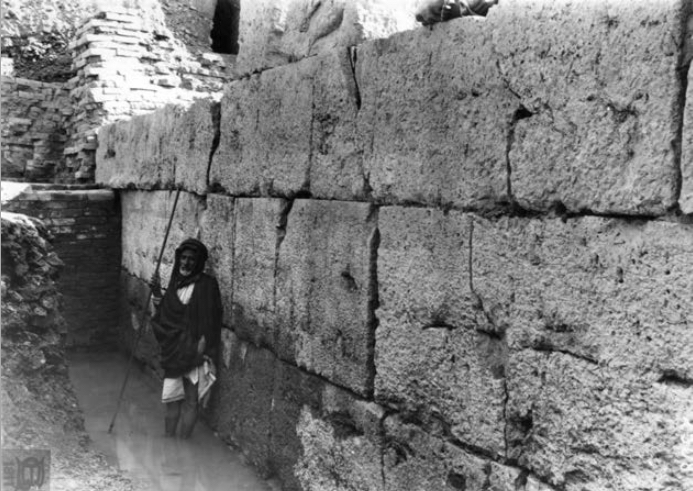

Six limestone ashlar blocks discovered in situ in the North Palace (Kasr 4q–r) at Babylon, in the third and fourth courses, are each inscribed with a three-line Akkadian text of Nebuchadnezzar II. This inscription written in archaizing Neo-Babylonian script records that he built (some of) the (outer) stone walls of the North Palace. The script is large and of the same size as the cuneiform signs in the Ištar Gate Inscription. Previous editions and studies generally refer to this inscription as "[Nebuchadnezzar] Ashlar [Inscription] (SQ1)" or "Nebuchadnezzar Ashlar I."

Access Nebuchadnezzar II 3 [ /ribo/babylon7/Q005474/].

Sources

| (1) BE 43218 | (2) BE 43219 |

| (3) BE 43323 | (4) BE 43324 |

| (5) BE 43325 | (6) BE 43326 |

Commentary

In addition to the six inscribed limestone blocks included in the catalogue, a number of inscribed stones engraved with this same inscription were uncovered in the northwest corner of the North Palace; for details, see Pedersén, Babylon pp. 116–117.

Because these massive ashlar blocks were left in situ, they were not available for firsthand examination and so the present edition is based on the hand-drawn facsimile of the inscription published in Koldewey, WEB5 (p. 178 fig. 111), but with the correct, three-line distribution. The text is presumed to have been written in three lines in all six known exemplars; this was the case for the three exemplars in Bab ph 2508 (fig. 12 of the present volume). No score of the inscription is presented on Oracc and no minor (orthographic) variants are given at the back of the book, in the critical apparatus, since none of the exemplars could be properly transliterated; the text on exs. 1 and 3–4 in Bab ph 2508 are not legible and there are no copies or photographs of exs. 2 and 5–6.

Bibliography

BE 43218, BE 43323, and BE 43324 (Nbk. 3 exs. 1, 3–4), three inscribed stone blocks discovered in situ in the North Palace that are each inscribed with a short text of Nebuchadnezzar II. © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Vorderasiatisches Museum, Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft. Photo: Gottfried Buddensieg, 1911.

This fragmentarily-preserved, eleven-line Akkadian inscription of Nebuchadnezzar II recording the construction and decoration of the Ištar Gate at Babylon is known from a single limestone block that was unearthed by German archaeologists in 1902 in the ruins of the northern part of the south entrance of Babylon's most famous city gate, ca. 3m above the lower street level. This text, which is referred to in Assyriological literature as "[Nebuchadnezzar] Limestone Blocks 3 (LBl 3)" or "Nebuchadnezzar Limestone Blocks I, 3," states that the king had copper(-plated) statues of wild bulls and raging mušḫuššu-dragons stationed at its door-jambs; this (ornate) metalwork has not survived. The script is archaizing Neo-Babylonian.

Access Nebuchadnezzar II 4 [ /ribo/babylon7/Q005475/].

Source

| BE 18465 |

Commentary

Because this massive stone block was left at Babylon and, therefore, not available for firsthand examination, the present edition is based on Bab ph 199, which is reproduced in the present volume (as fig. 18).

Bibliography

BE 18465 (Nbk. 4), a large limestone block that is inscribed with an inscription recording the construction and decoration of the Ištar Gate at Babylon. © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Vorderasiatisches Museum, Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft. Photo: Robert Koldewey, 1902.

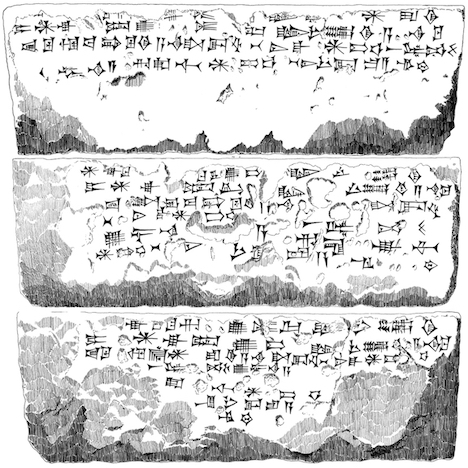

A six-line Akkadian inscription of Nebuchadnezzar II known from fifteen limestone blocks discovered during the German excavations at Babylon records that this Babylonian king paved Babylon's processional street with blocks (of limestone), thereby beautifying the route between Esagil and the New Year's House (Esiskur). The script of all fifteen exemplars is archaizing Neo-Babylonian. Scholarly literature generally refers to this text as "[Nebuchadnezzar] Limestone Blocks 2 (LBl 2)" or "Nebuchadnezzar Limestone Blocks I, 2."

BE 7689, BE 7706, and BE 7707 (Nbk. 5 exs. 1, 5–6), stone blocks with a text recording Nebuchadnezzar II's work on Babylon's processional way. Reproduced from Koldewey, Pflastersteine pls. 1–3.

Access the composite text [/ribo/babylon7/Q005476/] or the score [/ribo/bab7scores/Q005476/score] of Nebuchadnezzar II 5.

Sources

| (1) BE 7689 | (2) BE 7688 |

| (3) BE 488 | (4) BE 7690 |

| (5) BE 7706 | (6) BE 7707 |

| (7) IM — (BE 7698) | (8) VA — (BE 535) |

| (9) BE 549 | (10) VA — (BE 4698) |

| (11) BE 41580 | (12) BE 19927 |

| (13) BE 19928 | (14) BE 19929 |

| (15) BE 19930 |

Commentary

According to O. Pedersén, 375 inscribed paving stones were registered during R. Koldewey's excavations at Babylon: 153 limestone, 80 breccia, 35 basalt, 33 sandstone, and the rest not specified. Among the 153 limestone paving stones, 106 come from the Kasr, 40 from Tell Babil, 3 from Amran, and 1 from the Sahn. Of those, at least twenty-five are said to be inscribed with a text recording Nebuchadnezzar's work on the processional way: Twenty-three originate from the Kasr (Nbk. 5 [this text] exs. 1–10, 12–15; Nbk. 6 [LBl 1] ex. 2), one from Amran (Nbk. 6 ex. 1), and one from the Sahn (Nbk. 5 ex. 11). Of the blocks registered as coming from the Kasr, fifteen are included in the present volume. For the other limestone paving stones from Babylon, see the commentary to Nbk. 8 (PS1).

The limestone blocks with this text (LBl 2) and the following text (LBl 1) measure 105×105×33–35 cm. These large stones were used to pave the middle section of the northern 500-m stretch of the processional street that ran south-north outside the (old) South Palace and the (new) North Palace and through the monumental Ištar Gate; smaller, inscribed breccia blocks (66×66×20 cm), specifically those bearing Nbk. 7 (BP1), were placed on the sides of the street. These stones were always placed above the uppermost layer of bricks, so every time the street level was raised they were removed and set back in place; according to Nbk. 34 (C214), this happened three times while Nebuchadnezzar II was king. According to Pedersén (Babylon p. 275), approximately 2,500 limestone and 7,000 breccia blocks were used to pave the south-north processional way; most, if not all, had inscriptions engraved on their edges. Moreover, Pedersén (Babylon pp. 21 and 38) states that Koldewey's excavations at Babylon registered approximately 400 pavement stones.

Most of the known exemplars of this Akkadian inscription were left at Babylon, thereby making them inaccessible for firsthand examination at the present time. According to information kindly provided by Pedersén, ex. 7 (BE 7698) is now in the Iraq Museum (Baghdad) and exs. 8 (BE 535) and 11 (BE 4698) are currently housed in the Vorderasiatisches Museum (Berlin). Because none of these three objects have been assigned a museum number, the authors were unable to collate the inscriptions engraved on them since the stone blocks could not be easily located. Therefore, the edition presented in this volume is based on the published hand-drawn facsimiles of the texts (Koldewey, Pflastersteine pls. 1 a–b, 2 c–d, and 3 f–g, i, k–l), with help from Bab ph 1174 and 1176 (for exs. 1 and 5–6); ex. 11 is photographed in Bab ph 2154–2155, but the text is not legible in either photograph. The master text is a conflation of several exemplars since none of the known exemplars are fully preserved. Following S. Langdon (NBK pp. 198–199 no. 30), the text is edited here as a six-line inscription, as on ex. 5 (BE 7706). Compare exs. 1–3, where the inscription is written in four lines, ex. 4 (BE 7690), where it is engraved in five lines, and ex. 6 (BE 7707), on which it is distributed over seven lines; see fig. 19, which includes copies of the four-, six-, and seven-line versions of the inscription. A score of the inscription is presented on Oracc and the minor (orthographic) variants are given in the critical apparatus at the back of the book.

With regard to ex. 11 (BE 41580), this object was originally regarded as being engraved with an inscription of Nabonidus; see, for example, Berger, NbK p. 345; Beaulieu, Nabonidus p. 40; and Schaudig, Inschriften Nabonids p. 343. The correct identification as a duplicate of a well-known inscription of Nebuchadnezzar II was made by Pedersén; for details, see Weiershäuser and Novotny, RINBE 2 pp. 81–82 Nbn. 6 (Paving Stone U). Because the inscription on this exemplar is no longer accessible, it is not included in the score. The same is true of exs. 12–15.

Apart from the distribution of the text and minor orthographic variants, this inscription is identical to Nbk. 6 (Lbl 1), with two exceptions: (1) the present text has ana šadāḫa bēli rabî Marduk, "for the procession of the great lord, the god Marduk," instead of [ana m]adāḫa bēli rabî Marduk, "[for the proc]ession of the great lord, the god Marduk," which is also used in Nbk. 7 (BP1); and (2) this inscription has ina libitti aban šadê, "with slab(s) of stone from the mountain(s)," in lieu of ina libitti abni ši[tiq šadê], "with slab(s) of stone quar[ried from the mountain(s)]."

Bibliography

Two limestone blocks discovered at Babylon in 1899 and 1900 are inscribed with an Akkadian inscription of Nebuchadnezzar II in archaizing Neo-Babylonian script. This four-line text states that the king of Babylon paved Ay-ibūr-šabû, Babylon's processional street, with stone hewn from the mountains. Previous editions and studies refer to this short inscription as "[Nebuchadnezzar] Limestone Blocks 1 (LBl 1)" or "Nebuchadnezzar Limestone Blocks I, 1."

Access the composite text [/ribo/babylon7/Q005477/] or the score [/ribo/bab7scores/Q005477/score] of Nebuchadnezzar II 6.

Sources

| (1) BE 6877 | (2) BE 492 |

Commentary

Both of the stone blocks recorded as being engraved with this four-line Akkadian inscription of Nebuchadnezzar II were left at Babylon, so neither exemplar could be examined firsthand. Therefore, the edition presented here is based on published hand-drawn facsimiles (Koldewey, Pflastersteine pls. 3 h and 4 m). A score of the inscription is presented on Oracc. Because the preserved contents of ex. 1 (BE 6877) and ex. 2 (BE 492) do not overlap, no minor (orthographic) variants are given at the back of the book. The restorations are generally based on Nbk. 7 (BP1). For further information about the limestone blocks engraved with this text, see the commentary of Nbk. 5 (LBl 2).

Bibliography

PTen breccia paving stones unearthed during the nineteenth-century German excavations at Babylon under the direction of R. Koldewey bear a five-line Akkadian inscription of Nebuchadnezzar II recording that he paved Babylon's processional street Ay-ibūr-šabû with slab(s) of breccia. This text, which is written in archaizing Neo-Babylonian script, is referred to as the "Breccia Flagstone [Inscription] (BP1)" or "Breccia Flagstones I, 1."

Access the composite text [/ribo/babylon7/Q005478/] or the score [/ribo/bab7scores/Q005478/score] of Nebuchadnezzar II 7.

Sources

| (1) VA — (BE 2819) | (2) VA — (BE 4593) |

| (3) VA — (BE 635) | (4) VA — (BE 4850) |

| (5) VA — (BE 4766) | (6) VA — (BE 4765) |

| (7) VA — (BE 4898) | (8) VA — (BE 7715) |

| (9) VAA 1350 (BE 13717) | (10) VAA 1387 (BE 39666) |

Commentary

According to information supplied by O. Pedersén, eighty inscribed breccia paving stones were registered during R. Koldewey's excavations at Babylon: fifty-eight come from the Sahn (at the processional street or nearby), sixteen from the Kasr, three from Amran, two from the Merkes, and one from Babil. Of those, seven blocks from the Kasr, two from the Sahn, and one from Amran are included in the catalogue above.

The blocks engraved with this text measure 66×66×20 cm. These stones were used to pave the sides of the 500-m stretch of the processional street that ran south-north outside the (old) South Palace and the (new) North Palace and through the monumental Ištar Gate; larger inscribed limestone blocks (105×105×33–35 cm), specifically those bearing Nbk. 5 (LBl 2) and 6 (LBl 1), were placed in the middle of the street. These stones were always placed above the uppermost layer. See the commentary of Nbk. 5 for more details. In addition, the 700-m-long southern stretch of the processional way was paved entirely with breccia stones measuring 59×59 cm; Pedersén (Babylon p. 275) estimates that the reddish-colored section of this 1,200-m-long south-north street was paved with 9,000 slabs of breccia. The faces of some of the blocks discovered around the main entrance to the ziggurat precinct (BE 13717 and BE 39666) also had a two-line text of the Neo-Assyrian king Sennacherib (r. 704–681) on their down-facing surface; see Grayson and Novotny, RINAP 3/2 pp. 337–339 Senn. 232. Paper casts of this text on BE 13717 (Bab ph 1175) and BE 39666 (Bab ph 2040) are in the Vorderasiatisches Museum (Berlin): the museum numbers are VAA 1349 and VAA 1390 respectively.

R.-P. Berger (NBK p. 175) and R. Da Riva (GMTR 4 p. 124) list nine exemplars, but, according to information kindly provided by Pedersén, BE 492 (Berger, Breccia-Platten I, 1/9) is actually a limestone block, rather than a breccia paving stone. Therefore, that object is edited in the present volume as ex. 2 of Nbk. 6 (LBl 1). According to Pedersén, most exemplars of this Akkadian inscription are currently housed in the Vorderasiatisches Museum, but without museum numbers. Because the original fragments were not easily accessible for firsthand examination, the present edition is generally based on hand-drawn facsimiles of the inscriptions (Koldewey, Pflastersteine pl. 4 n–u). Note that exs. 9–10 were collated from unpublished photographs of paper casts in Vorderasiatisches Museum; the images were provided by Pedersén. Because none of the exemplars is complete, the edition provided here is a conflated text, which is generally based on the proposed "complete" text presented on Koldewey, Pflastersteine pl. 4 n. As far as it is possible to tell, the inscription was distributed over five lines on most of the exemplars; ex. 3 (BE 635), however, might have the text in six lines. Following RINBE editorial guidelines, a score of the inscription is presented on Oracc and the minor (orthographic) variants are given at the back of the book, in the critical apparatus.

Apart from the distribution of the text and minor orthographic variants, this inscription is identical to Nbk. 6 (Lbl 1), with one exception: the present text has ina libitti turminabandî, "with slab(s) of breccia," instead of ina libitti abni ši[tiq šadê], "with slab(s) of stone quar[ried from the mountain(s)]."

Bibliography

Fragments of three limestone paving stones bear a two-line Akkadian proprietary inscription of the Neo-Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II; the script of all three exemplars is archaizing Neo-Babylonian. One exemplar (ex. 2) was discovered by German archeologists in the ruins of the South Palace (Kasr 26s) at Babylon, while another exemplar (ex. 1) is reported to have come from the Elamite capital Susa, in modern-day Iran. The text is referred to in earlier scholarly literature as "[Nebuchadnezzar] Paving Stone 1 (PS1)" or "Nebuchadnezzar Flagstones I, 1."

Access the composite text [/ribo/babylon7/Q005479/] or the score [/ribo/bab7scores/Q005479/score] of Nebuchadnezzar II 8.

Sources

| (1) AO 4807 (Sb 18260) | (2) BE 8195 |

| (3) VA Bab 4500 |

VA Bab 4500 (Nbk. 8 ex. 3), a limestone paving stone with a two-line proprietary inscription of Nebuchadnezzar II. © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Vorderasiatisches Museum. Photo: Olaf M. Teßmer.

Commentary

According to O. Pedersén, 153 limestone paving stones were registered during R. Koldewey's excavations at Babylon. Of those, at least seventy-three are said to have been inscribed with short, one- or two-line proprietary inscriptions of Nebuchadnezzar II. Of these, at least thirty-two originate from the Kasr (Nbk. 8 [this text] ex. 2; Nbk. 9 [PS2] exs. 1–15), forty from Tell Babil, and one from the Merkes. Of the blocks registered from the Kasr, only sixteen are included in the present volume. For the other limestone paving stones from Babylon, see the commentary to Nbk. 5 (LBl 2).

Some of the floors of the North Palace had paving stones of limestone, sandstone, and basalt; these measured 66×66 cm. An unspecified number of these were inscribed on the edge with short proprietary inscriptions of Nebuchadnezzar II; the texts in question are the present text and Nbk. 9 (PS2). Pedersén (Babylon p. 126) estimates that the (new) North Palace might have used around 5,600 of them to pave its two main courtyards; most of these stones had been removed by locals prior to the start of Koldewey's excavations. The courtyards of the Summer Palace also were paved with inscribed paving stones; approximately 100 such slabs, mostly limestone, were registered during the German excavations of that royal residence. Pedersén (ibid. p. 137) has suggested that 6,430 of them would have been needed to pave that palace's two central courtyards.

Two of the three published paving stones with this two-line Akkadian inscription of Nebuchadnezzar II come from Babylon, while the third (ex. 1) was discovered at Susa, the Elamite religious capital (in modern-day Iran). Ex. 1 (AO —) is in the Louvre Museum (Paris), with the museum number AO 4807 assigned to it, while ex. 3 (VA Bab 4500) is currently housed in the Vorderasiatisches Museum (Berlin). The present whereabouts of ex. 2 (BE 8195) is not known; however, its inscription is legible in Bab ph 1167 and 2410. All three exemplars of this text could be collated from published photographs, including Babylon excavation photo Bab ph 1167. The master text generally follows ex. 2, the best preserved of the three exemplars. A score is presented on Oracc and the minor (orthographic) variants are given at the back of the book.

Bibliography

Fifteen limestone paving stones discovered in the Kasr (squares 4t–u), near the North Palace, at Babylon are reported to be inscribed with a short proprietary inscription of Nebuchadnezzar II; this Akkadian text apparently began with "Palace of Nebuchadnezzar (II)." Because no on-the-spot copy ("Fundkopie"), excavation photograph, transliteration, or translation of this text has ever been published, no edition of it is presented in this volume. This inscription might, like the previous text (Nbk. 8 [PS1]), have also been written in archaizing Neo-Babylonian script. This text is sometimes referred to as "[Nebuchadnezzar] Paving Stone 2 (PS2)" and "Nebuchadnezzar Flagstones U."

Access Nebuchadnezzar II 9 [ /ribo/babylon7/Q005480/].

Sources

| (1) VA — (BE 42689) | (2) BE 42690 |

| (3) VA — (BE 42691) | (4) VA — (BE 42692) |

| (5) BE 42693 | (6) VA — (BE 42694) |

| (7) VA — (BE 42695) | (8) VA — (BE 42696) |

| (9) VA — (BE 42697) | (10) BE 42698 |

| (11) BE 42699 | (12) BE 42700 |

| (13) VA — (BE 42701) | (14) VA — (BE 42702) |

| (15) VA — (BE 42703) |

Commentary

According to O. Pedersén, most of the recorded fifteen exemplars are in the Vorderasiatisches Museum (Berlin). Because none of these objects have been assigned a museum number, the authors were unable to collate the inscriptions engraved on them. Therefore, as mentioned above, no edition of the inscription is presented here. For further information on the paving stones of Nebuchadnezzar II used for the floors of the courtyards of the North Palace and South Palace, see the commentary of Nbk. 8 (PS1).

Bibliography

A marble paving stone, reportedly from a door at Babylon, is inscribed with a three-line Akkadian inscription of Nebuchadnezzar II written in archaizing Neo-Babylonian script. This text, which is referred to in previous editions and studies as "[Nebuchadnezzar II] Door Stone I" or (wrongly) as "[Nebuchadnezzar II] Door Socket (TS 1)," is a short proprietary inscription with epithets reporting that the king provided for Esagil at Babylon and Ezida at Borsippa and acted at the behest of those two temples' patron deities, Marduk and Nabû.

Access Nebuchadnezzar II 10 [ /ribo/babylon7/Q005481/].

Source

| AO 7376 |

Bibliography

Jamie Novotny & Frauke Weiershäuser

Jamie Novotny & Frauke Weiershäuser, 'Inscriptions of Nebuchadnezzar II from Babylon', RIBo, Babylon 7: The Inscriptions of the Neo-Babylonian Dynasty, The RIBo Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, 2024 [/ribo/babylon7/Rulers/NebuchadnezzarII/Texts1-10Babylon/]