Eanna (temple of Ištar at Uruk)

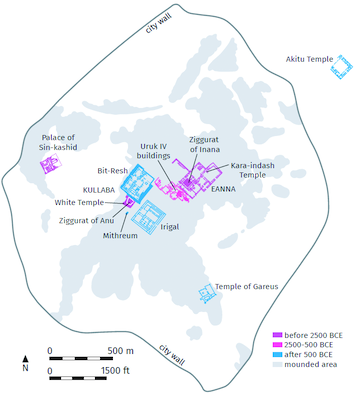

Eanna, the temple of Inanna/Ištar (the goddess of sexual love and war), together with its ziggurat Egiparimin ("House of the Seven Giparu's"), dominated the landscape of Uruk from the Ur III Period (ca. 2112–2004 BC) until the reign of the Persian king Xerxes I (r. 485–465 BC), who destroyed it after putting down a rebellion in southern Babylonia; Ištar's cult was revived in the Seleucid Period (323–63 BC), but on a much smaller scale. The size of the Eanna temple complex was truly impressive. According to the Standard Babylonian Version of the Poem of Gilgamesh ("He Who Saw the Deep"), it occupied nearly thirty percent of the city: "[One šār is] city, [one šār] date-grove, one šār is clay-pit, half a šār the temple of Ištar: [three šār] and a half, Uruk, (its) measurement." German excavations at Uruk have confirmed that Eanna took up a significant portion of the city (ca. six hectares).

Names and Spellings

Uruk's principal temple went by the Sumerian ceremonial name Eanna, which means "House of Heaven." Its Akkadian name was Ayakkum, which was also used as a common noun for a type of sanctuary in Akkadian texts.

- Written Forms: a-a-ak; a-a-ak-ki; e₂-an-na; E₂.AN.NA.

Plan of Uruk showing the locations of Eanna (with its ziggurat), the Rēš Temple, and Eʾešgal. Drawn by Ardeth Anderson for the Lagash Archaeological Project (LAP).

Known Builders

- Old Akkadian (ca. 2340–2200 BC)

- Narām-Sîn (r. 2254–2218 BC)

- Ur III (ca. 2100–2000 BC)

- Ur-Namma (r. 2112–2095 BC)

- Šulgi (r. 2094–2047 BC)

- Amar-Suena (r. 2046–2038 BC)

- Early Old Babylonian (ca. 2000–1750 BC)

- Sîn-kāšid

- Anam

- Old Babylonian (ca. 1900–1600 BC)

- Hammu-rāpi (r. 1792–1750 BC)

- Middle Babylonian (ca. 1600–1000 BC)

- Kara-indaš

- Kurigalzu I

- Early Neo-Babylonian (ca. 1000–710 BC)

- Marduk-apla-iddina II (r. 721–710, 703 BC)

- Neo-Assyrian (ca. 911–612 BC)

- Sargon II (r. 721–705 BC)

- Esarhaddon (r. 680–669 BC)

- Ashurbanipal (r. 668–ca. 631 BC)

- Neo-Babylonian (ca. 625–539 BC)

- Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 604–562 BC)

- Nabonidus (r. 555–539 BC)

- Achaemenid (547–331 BC)

- Cyrus II (r. 559–530 BC)

Building History

Archaeological excavation has shown that a monumental temple existed at the location of the later Eanna temple already as early as the Uruk III Period (ca. 3200 BC). Eanna is mentioned in various early pieces of Sumerian literature, including a collection of temple hymns attributed to En-hedu-ana, a daughter of Sargon of Agade (r. 2334–2279 BC). In Akkadian texts, Eanna's earliest attestation is in the Basetki inscription of Narām-Sîn, Sargon's grandson, where the temple is called "Ayakkum."

A watershed in the temple's history is the reign of the Ur-III ruler Ur-Namma, during which the older buildings in the temple precinct were razed and the temple was rebuilt according to an innovative design, on top of two terraces (a ziggurat; from Akkadian ziqquratu) made of mudbricks and reed bundles (see the archaeological remains section for further details). From that time until the fifth century BC, Eanna dominated Uruk's landscape and occupied a significant portion of the city. The six-hectare temple complex constructed by Ur-Namma, with its four courtyards and enclosure wall, was undoubtedly the largest structure in Uruk. Inscriptions composed some 1,300 years later, in the names of the eighth-century-BC Babylonian and Assyrian kings Marduk-apla-iddina II and Sargon II, indicate that Šulgi, Ur-Namma's son and immediate successor, and Anam (r. 19th century BC), an Early Old Babylonian ruler of Uruk sponsored building work in the Eanna precinct. Anam's work on the gipar, the residence of the en-priestess of Eanna's goddess Inanna/Ištar, as well as on Eanna in general, is also attested in Sumerian inscriptions from his reign.

After the collapse of the Ur III Empire, the enclosure wall and the courtyards were renovated by Sîn-kāšid (r. 19th century BC), an Early Old Babylonian ruler of Uruk. Hammu-rāpi, the sixth king of the First Dynasty of Babylon, also sponsored restoration work on Eanna, as indicated by one of his epithets in his "Law Code": "the one who raises high the summit of Eanna" (Akkadian mulli rēš eanna). Later, in the Middle Babylonian Period (ca. 1400–1000 BC), the ziggurat received a new outer layer and the "Ziggurat Courtyard" and the "Pillared Courtyard" were replastered, possibly in the reigns of Kara-indaš (r. 15th century BC) and/or Kurigalzu I (r. 14th century BC), whose inscriptions on baked bricks recording their building work on Eanna have survived.

Façade of the Kara-indaš temple. Photo credit: Marcus Cyron

After the Kassite Period, the next earliest evidence for renovation work on this temple of Ištar dates to late eighth century BC, during the reigns of the Babylonian king Marduk-apla-iddina II (Merodach-baladan of the Old Testament), and the Assyrian king Sargon II, who also ruled over Babylon from 709 BC until his death in 705 BC. Both rulers claim to have sponsored a thorough renovation. An Akkadian inscription of Marduk-apla-iddina II written on clay cylinders portrays the temple's history in the following manner:

Further work was already necessary under Sargon's grandson Esarhaddon and great-grandson Ashurbanipal.

In conjunction with his restoration of the cult statue and cult of Ištar, Nebuchadnezzar II, the long-reigning second king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, sponsored a wholesale restoration of the temple. An Akkadian inscription written on a clay cylinder, presumably from Uruk, records the following:

Bricks of Nabonidus, the last native king of Babylon, found at Uruk probably indicate that he also sponsored work on the Eanna, even though the brief inscription on the bricks does not mention the temple. The so-called "Uruk Stele" (inscription obliterated), if correctly attributed to Nabonidus, would also testify to his work on the temple. A single brick of Cyrus II found at Uruk may indicate that he also financed work on Eanna, although the brief inscription also does not mention the temple.

Years of political conflict between Babylonia's priesthood and their Achaemenid rulers, culminated in the destruction of Eanna, probably during the reign of Xerxes I (r. 486–465 BC). In the latter part of the Achaemenid Period (547–331 BC), the goddesses Ištar and Nanāya found a new home in the Eʾešgal (or possibly called Eirigal) temple. Nevertheless, archaeological excavation indicates that during the Hellenistic Period (323–63 BC) Eanna's ziggurat was renovated and enlarged (see below).

Archaeological Remains

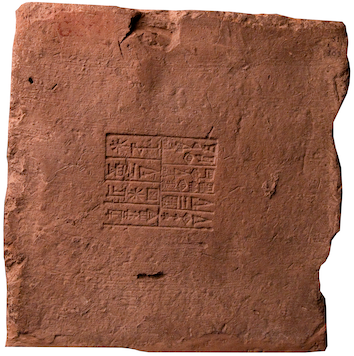

The substantive remains of the sprawling, six-hectare Eanna complex, including its ziggurat Egiparimin, were excavated by the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft (DOG) and Deutsches Archäologisches Institut (DAI). Various building phases of this important Ištar temple from the Ur III Period (reign of Ur-Namma and his successors) to the Seleucid Period, as well as that of numerous earlier temples in the Eanna precinct, have been unearthed. In-situ bricks and clay foundation documents (cones/nails and cylinders) deposited in the temple's brick structure provide the names of some of Eanna's Assyrian, Babylonian, Persian, and Sumerian builders from Ur-Namma to Cyrus II. The massive mudbrick core of the ziggurat, as well as traces of its façade and staircase, are still visible today.

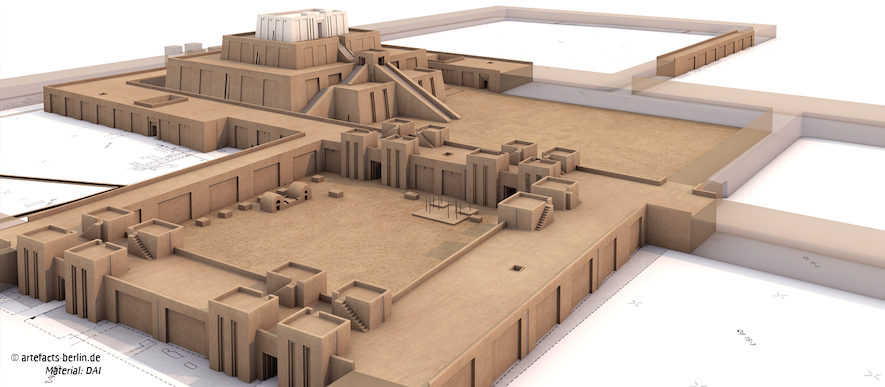

Digital reconstruction of the Eanna temple complex, with its ziggurat Egiparimin, during the reign of Ur-Namma, the founder of the Ur III dynasty. Image credit: Uruk Visualisation Project (© artefacts-berlin.de).

Although the Eanna district evolved from the Ubaid IV Period onwards, it was not until the reign of Ur-Namma that the buildings in that area can be directly linked to the goddess Inanna/Ištar. Before construction began, that Ur III king razed all of the older structures, dug a huge pit, and constructed a (slightly-trapezoidal-shaped) brick platform to level the uneven building site. Ur-Namma built a completely redesigned Eanna on top of that brick foundation, which might have had cosmological significance since it resembled the constellation known in antiquity as the "Field" (Akkadian ikû) and to us as the "Square of Pegasus." The ziggurat was reconfigured as a high temple atop two terraces. The lowest stage, which was well preserved, measured 48×56 m and was 11.2 m tall. The second terrace, whose maximum preserved height was 3.2 m, might have been only half as tall as the base, that is, 5.6 m tall. The core was constructed of mudbricks, with layers of bundled reeds every 1.2–4 m. The terrace surfaces were built with baked bricks and the façades were coated with a layer of plaster. The main temple on top, which was dedicated to Inanna, was accessed from the northeast façade via a three-wing staircase and then a smaller single-flight of stairs; both of the lateral staircases were interrupted by smaller side terraces. No traces of the main temple itself have survived. In addition, Ur-Namma and his immediate successor Šulgi built a large, six-courtyard complex around the ziggurat. Access to the main sanctuary was from the southeast of the "Ziggurat Courtyard," via the two northern entrances of the "Pillared Courtyard," which had a number of pedestals (probably for cult statues/images) along the southwest wall.

The Eanna temple built by Ur-Namma was regularly maintained and repaired until the time of the Persian king Xerxes I. An Old Babylonian ruler, Sîn-kāšid (or Anam) extensively renovated the complex's enclosure wall and courtyards; the identity of that king cannot be confirmed archaeologically. During the Middle Babylonian Period, the Kassite Dynasty rulers Kara-indaš and one of the Kurigalzus (probably the first king with that name) sponsored thorough renovations of Ištar's temple. The former ruler constructed a building with an ornately-decorated façade constructed from molded bricks; that temple was maintained until the Seleucid Period. In the early Neo-Babylonian Period and the late Neo-Assyrian Period, the ground plan of the temple complex was slightly modified, with changes made to the courtyards and enclosure walls. Some of these alternations, perhaps those made by Marduk-apla-iddina II or Sargon II, are mentioned in an Akkadian inscription of Nebuchadnezzar II stating that Eanna's "plan had been destroyed."

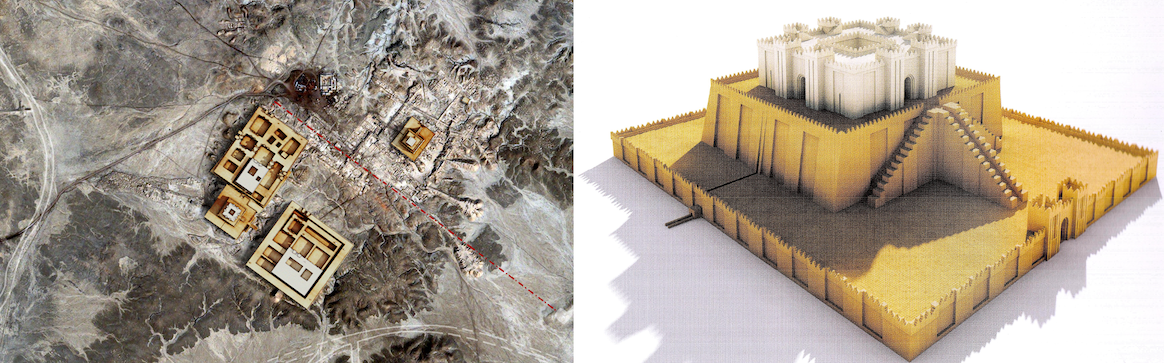

Digital reconstruction of Uruk's temples in the Seleucid Period, with the bīt rēš (Rēš Temple) and Eʾešgal (or possibly called Eirigal) temples on the left and the Eanna ziggurat (Egiparimin) on the right (left); digital reconstruction of the Ištar ziggurat in the Seleucid Period (right). Image created by Jamie Novotny from the Uruk Visualisation Project (© artefacts-berlin.de).

In the Seleucid Period, Eanna was rebuilt, but on a significantly smaller scale, in an area that was smaller than the "Ziggurat Courtyard" of the Ur-Namma temple complex. The walls surrounding the ziggurat and its high temple were razed and then replaced by a five-meter-high brick terrace. The ziggurat, with its elevated courtyard, was also rebuilt on a much smaller scale: the main temple sat atop a single, high mudbrick terrace. It was reached by a steep, three-wing staircase. Access to the new temple grounds was provided by a gate just northeast of the central staircase. Moreover, at this time, Eanna ceased to be Ištar's principal residence. Her new home was Eʾešgal (or possibly called Eirigal), a massive 198×205-m temple that was located 240 m southwest of the once-grand Eanna temple.

Further Reading

- Beaulieu, P.-A. 2002. "Eanna = Ayakkum in the Basetki inscription of Narām-Sîn," Nouvelles assyriologiques bréves et utilitaires 2002 no. 36.

- Eichmann, R. 2007. Uruk: Architektur. 1, Von den Anfängen bis zur frühdynastischen Zeit (Ausgrabungen in Uruk-Warka Endberichte 14), Rahnden.

- Eichmann, R. 2019. "Uruk's Early Monumental Architecture," in T. Potts (ed.), Uruk: First City of the Ancient World (= English edition of N. Crüsemann, M. van Ess, M. Hilgert, and B. Salje (eds.), Uruk: 5000 Jahre Megacity, Berlin, 2013), Los Angeles, pp. 97–107.

- Da Riva, R. and Novotny, J. 2023. "A Cylinder of Nebuchadnezzar II from Uruk in the Collection of David and Cindy Sofer, London, Displayed in the Bible Lands Museum Jerusalem," in Y. Cohen, A. Gilan, N. Wasserman, L. Cerqueglini, and B. Sheyhatovitch (eds.), The IOS Annual 22: "Telling of Olden Kings", pp. 3–29.

- van Ess, M. 2001. Uruk: Architektur 2. Von der Akkad- bis zur mittelbabylonischen Zeit, vol. 1, Das Eanna Heiligtum zur Ur III- und altbabylonischen Zeit (Ausgrabungen in Uruk-Warka Endberichte 15/1), Mainz am Rhein.

- van Ess, M. 2015. "Uruk. B. Archäologisch," Reallexikon der Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie 14/5–6, pp. 457–487.

- van Ess, M. 2019. "The Eanna Sanctuary in Uruk," in T. Potts (ed.), Uruk. First City of the Ancient World (= English edition of N. Crüsemann, M. van Ess, M. Hilgert, and B. Salje (eds.), Uruk: 5000 Jahre Megacity, Berlin, 2013), Los Angeles, pp. 205–211.

- George, A.R. 1993. House Most High: The Temples of Ancient Mesopotamia (Mesopotamian Civilizations 5), Winona Lake, pp. 67–68 no. 75.

- Hageneuer, S. 2014. "The visualisation of Uruk – First impressions of the first metropolis in the world," in W. Börner and S. Uhlirtz (eds.), Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Cultural Heritage and New Technologies 2013, Vienna, pp. 1–12.

- Kose, A. 1998. Uruk: Architektur 4: von der Seleukiden bis zur Sasanidenzeit (Ausgrabungen in Uruk-Warka Endberichte 17), Mainz am Rhein.

Banner image: view of the Eanna ziggurat from the east (September 27th 2019). Photograph credit: Mary Frazer.

Mary Frazer, Jamie Novotny & Joshua Meynell

Mary Frazer, Jamie Novotny & Joshua Meynell, 'Eanna (temple of Ištar at Uruk)', Babylonian Temples and Monumental Architecture online (BTMAo), The BTMAo Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, [http://oracc.org/btmao/Uruk/Eanna/]