Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil (inner city walls of Babylon)

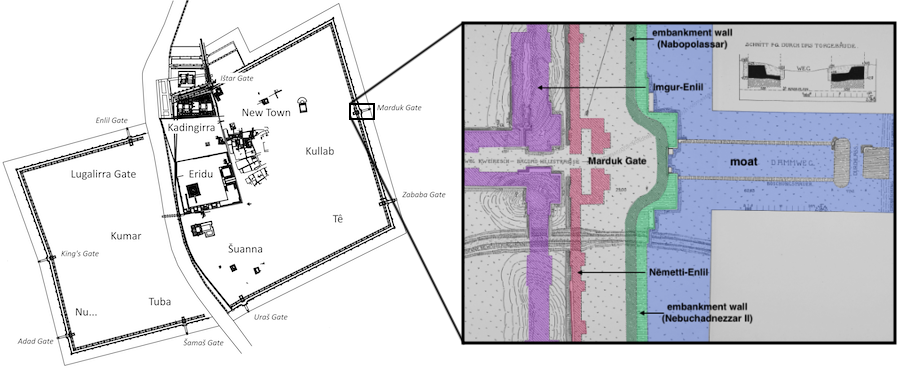

The inner city of Babylon was enclosed by a main wall (Akkadian dūru) and an outer wall (Akkadian šalhû) constructed from mudbrick, embankment walls (Akkadian kāru) made of baked brick and bitumen, and a water-filled moat (Akkadian hirītu). Access to and from the ten city quarters was provided by eight gates, four on each side of the Arahtu River, an arm of the Euphrates that divided the city in two. Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil, according to one classical author, were one of the seven wonders of the world.

Names and Spellings

Babylon's main city wall (dūru) and outer wall (šalhû) bear the Akkadian ceremonial names Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil, which mean "Enlil Has Shown Favor" and "Bulkwark of Enlil" respectively.

- Written Forms: im-gu-úr-d50; im-gu-úr-dEN.LÍL; im-gur-d50; BÀD.im-gur-dEN.LÍL; im-gur-dEN.LÍL; né-mé-et-ti-dEN.LÍL; né-mé-et-tì-d50; né-mé-et-tì-dEN.LÍL; né-met-d50; BÀD.né-met-dEN.LÍL; né-met-dEN.LÍL; né-met-ti-dEN.LÍL.

Known Builders

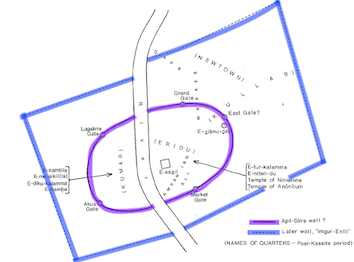

Annotated plan of Babylon and its city wall before the reign of Hammu-rāpi (r. 1792–1750 BC), the sixth king of the First Dynasty of Babylon. Adapted from A.R. George, Babylonian Topographical Texts, p. 20 fig. 3.

- Middle Babylonian (ca. 1400–1100 BC)

- Adad-šuma-uṣur (r. 1216–1187 BC)

- Marduk-šāpik-zēri (r. 1081–1069 BC)

- Adad-apla-iddina (r. 1068–1047 BC)

- Neo-Assyrian (ca. 911–612 BC)

- Sargon II (r. 721–705 BC)

- Esarhaddon (r. 680–669 BC)

- Ashurbanipal (r. 668–631 BC)

- Neo-Babylonian (ca. 625–539 BC)

- Nabopolassar (r. 625–605 BC)

- Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 604–562 BC)

- Nabonidus (r. 555–539 BC)

- Achaemenid (547–331 BC)

- Cyrus II (r. 559–530 BC)

Building History

A city wall surrounding the inner city of Babylon, together with at least five gates, is attested in sources from the Old Babylonian Period (ca. 1900–1600 BC), including the year names for the rulers Sūmû-abum (Year 1 = 1894 BC), Sūmû-lā-El (Year 5 = 1876 BC), and Apil-Sîn (Year 2 = 1829 BC and Year 15 = 1816 BC). On the basis of information provided in the scholarly compendium Tintir = Babylon, as well as in Old Babylonian sources, it is often assumed that the circuit of the old, pre-Hammu-rāpi wall (ca. 1894–1793 BC) was significantly smaller than that of the later, rectangular-shaped one.

The traditional, rectangular-shaped city wall might have been planned and constructed sometime between 1730 BC, the nineteenth year of Samsu-iluna (r. 1749–1712 BC), and 1614 BC, the eleventh year of Samsu-ditāna (1614 BC), the last monarch of the First Dynasty of Babylon; the Ištar Gate — one of the eight gates associated with the rectangular, double walls Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil in Tintir = Babylon — and the city wall associated with it existed at least by 1614 BC. Due to the high water table at Babylon, as well as the remains of numerous later building activities (especially from the seventh and sixth centuries BC), it is not possible to determine whether or not Babylon's city wall at the end of the seventeenth century BC had the exact same circuit as it did during the Second Dynasty of Isin (ca. 1157–1026 BC), when kings Marduk-šāpik-zēri (r. 1081–1069 BC) and Adad-apla-iddina (r. 1068–1047 BC) sat on the throne.

According to a late Babylonian historical-literary composition known as the "Adad-šuma-uṣur Epic," Babylon's main wall was called lmgur-Enlil at least by the end of the thirteenth century BC, assuming, of course, that the names of that late Kassite king and Babylon's city wall were not anachronisms. Adad-šuma-uṣur (r. 1216–1187 BC), according to that late source, undertook construction on the city wall and its gates. This might have been because Babylon, its walls, and its temples had suffered badly when the Assyrian ruler Tukultī-Ninurta I (r. 1243–1207 BC) had sacked the city; "Babylonian Chronicle P" states that the Assyrian "tore down the city wall of Babylon" and, therefore, it would have needed rebuilding.

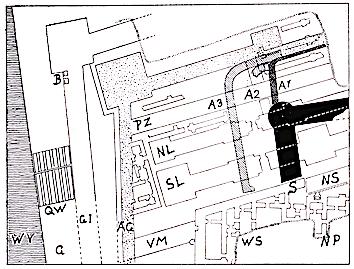

Plan of the location of Imgur-Enlil, Nēmetti-Enlil, and embankment walls northwest of the South Palace during the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian Periods. "Sargon II wall" is marked S and the later "Arahtu Walls" of Nabopolassar are marked A1–3. Reproduced from R. Koldewey, Das wieder erstehende Babylon, fifth edition, p. 138 fig. 81.

The earliest contemporary references to Imgur-Enlil come from royal inscriptions dating to the reigns of Marduk-šāpik-zēri and his immediate successor Adad-apla-iddina, respectively the sixth and seventh kings of the Second Dynasty of Isin (ca. 1157–1026 BC). In an Akkadian inscription written on a fragmentarily-preserved clay cylinder, the former ruler states that he strengthened Imgur-Enlil and its gates after Babylon was flooded by the Euphrates River. The latter king, if the attribution of a heavily-damaged Sumerian inscription written on a clay cylinder to him is correct, records that he had (part of) Imgur-Enlil rebuilt since it had become old and dilapidated. Adad-apla-iddina's work is attested by a fragment of a brick discovered near the Zababa Gate, the southern gate of the wall's eastern stretch. The find spots of that brick and that still-to-be-positively-identified cylinder indicate that the circuit of Imgur-Enlil was the same during the Second Dynasty of Isin as it was in the late Neo-Assyrian (721–626 BC) and Neo-Babylonian (625–539 BC) Periods.

Starting with the reign of the eighth-century-BC Assyrian king Sargon II (r. 721–705 BC), work on Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil, together with their embankment walls, is regularly recorded in royal inscriptions. Between 710 BC and 539 BC, no less than six Assyrian and Babylonian rulers claim to have rebuilt (parts of) Babylon's inner city walls. The work of several of these kings can be confirmed from the archaeological record, principally from in situ bricks bearing inscriptions written in their names. The first Persian king Cyrus II (r. 559–530 BC) is known also to have worked on Imgur-Enlil; he is its last certainly-attested builder.

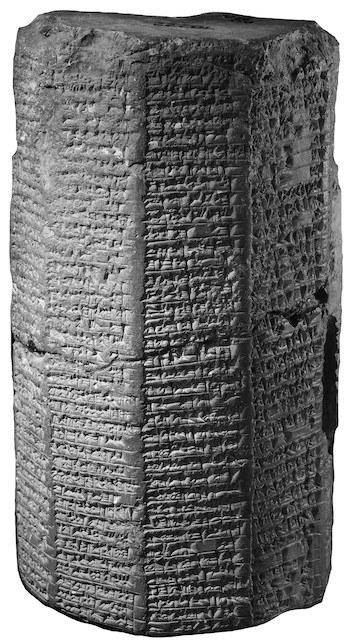

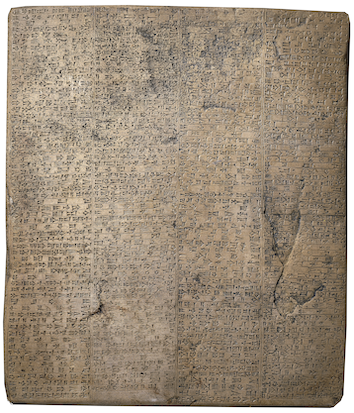

BM 078221+, a ten-sided clay prism of the Assyrian king Esarhaddon that records his rebuilding of Babylon and its walls. Image adapted from the British Museum Collection website. Credit: Trustees of the British Museum.

Bricks of Sargon bearing Akkadian and Sumerian inscriptions record that he worked on Babylon's embankment wall, as well as on Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil. This Assyrian ruler's claim to have constructed the quay wall (Akkadian kāru) with baked bricks (Akkadian agurru) and bitumen (Akkadian kupru) can be confirmed archaeologically, at least in the northwest corner of East Babylon, immediately northwest of the South Palace since part of that wall was excavated. Due to later rebuildings of the inner and outer wall, both of which were constructed of unbaked brick, Sargon's claims about renovating Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil cannot be corroborated.

In 689 BC, the Assyrian king Sennacherib (r. 704–681 BC) captured, looted, and destroyed Babylon, including the city's walls. Although the actual destruction was probably not as bad as that ruler described in his royal inscriptions (especially in the so-called "Bavian Inscription"), Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil almost certainly sustained damage in the immediate aftermath of Babylon's fall, as well as during the eight years that Babylonia was left kingless (688–681 BC). His son Esarhaddon, however, took it upon himself to repair all of the damage that his father's armies had wrought on Babylon and to restore that city, its temples, and its walls to their former glory. The work, at least according to several Akkadian inscriptions of his written on multi-column clay prisms, started shortly after Esarhaddon ascended the Assyrian throne and became the de facto ruler of Babylon. One of his inscriptions described the project as follows:

Despite the fact that Babylon's inner and outer walls were rectangular in shape, Esarhaddon's inscriptions regarded the circuit of the inner city as being a perfect square; some classical authors (Herodotus, C. Julius and Pliny the Elder) also saw this city as a square. It is unclear if that Assyrian king's image-makers actually saw Babylon as a square-shaped city (just like his grandfather Sargon II's capital city Dūr-Šarrukīn, which was modelled upon Babylon) or whether his measurements were only given for East Babylon, which was regarded as the more important half of the city. Although Esarhaddon claims to have completed the monumental task of rebuilding Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil, the work might have been unfinished at the time of his death in 669 BC since his son and successor on the Assyrian throne, Ashurbanipal, records that he also worked on Nēmetti-Enlil and its gates; at least one inscribed cylinder of his was reburied by Nabonidus, the last native ruler of Babylon, while he was making repairs to the walls. This work was carried out while his older brother Šamaš-šuma-ukīn (r. 667–648 BC) was the king of Babylon.

During the Neo-Babylonian Empire, especially during the reigns of Nabopolassar and his son and immediate successor Nebuchadnezzar II, Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil, as well as the embankment walls, were (entirely) rebuilt and reinforced. This is well attested in both the textual and archaeological records, including Akkadian inscriptions on baked bricks and clay cylinders. The work began under Nabopolassar and was completed by Nebuchadnezzar. The most detailed description of Imgur-Enlil's rebuilding comes from a text of Nabopolassar written on a three-column cylinder:

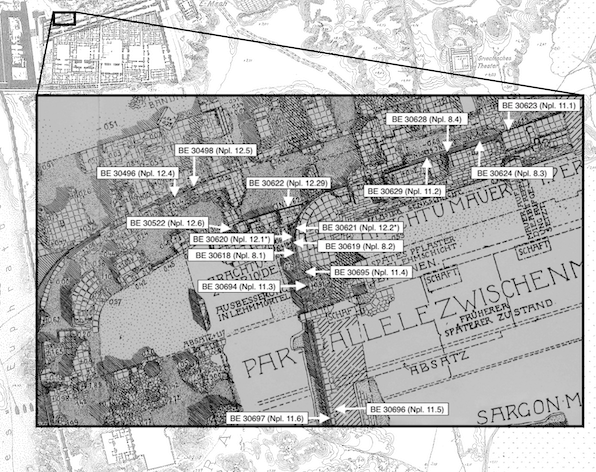

Nabopolassar, however, is far less verbose about his restorations of Nēmetti-Enlil, which he simply states that he had built anew and made shine like daylight. In order to better protect Babylon from water damage, he also actively reinforced the embankment wall, which he sometimes called the "Arahtu embankment" (Akkadian kār arahti), with baked brick (and bitumen). In situ bricks of his, especially in the northwest corner of East Babylon, just north of the South Palace, attest to Nabopolassar's efforts to keep water outside of his city.

Annotated plan of Babylon, with a detailed view of a section of the embankment wall of the Arahtu River (phases 1–3) north of the South Palace showing the find spots of sixteen inscribed, carved, and stamped bricks of Nabopolassar. Adapted by Jamie Novotny from F. Wetzel, Die Stadtmauern von Babylon, pl. 11.

Nebuchadnezzar II continued the work of his father after his death in 605 BC. He made Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil taller, as well as constructed additional embankment walls, most of which were built adjacent to the embankment built by Nabopolassar. Numerous Akkadian inscriptions, most of which are written on multi-column clay cylinders, describe these massive undertakings carried out while Nebuchadnezzar was transforming his capital into a wonder to behold. For example, one text records the following:

BM 129397, a large stone tablet that bears a long Akkadian inscription that is now commonly referred to as the "East India House Inscription." The description of Nebuchadnezzar's work on Babylon's city walls and embankments is recorded in lines iv 36–v 11 and 21–vi 21. Image adapted from the British Museum Collection website. Credit: Trustees of the British Museum.

In situ bricks attest to Nebuchadnezzar's efforts to strengthen his father's embankment walls. In connection with the rebuilding of Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil, as well as the raising of the level of the Processional Way, Nebuchadnezzar had to rebuild (some) of the city gates, especially the Ištar Gate, which was located in the north wall of East Babylon and which was the city's largest, grandest, and most important entrance.

Despite Nebuchadnezzar's best efforts, Babylon's city walls required attention a few decades later. That task fell on Nabonidus, Babylon's last native king. While renovating and reinforcing (sections of) Imgur-Enlil, Nabonidus has his workmen not only deposit his own clay cylinders in that wall's unbaked brick structure, but also those of earlier builders (Nabopolassar and Ashurbanipal) that had been found inside of it. The language of the Akkadian inscription recording Nabonidus' work on Babylon's inner wall was inspired by that of at least one of Nabopolassar's texts:

Although Nabonidus was later remembered for this deed in the "Dynastic Prophecy," he was not in the "Verse Account of Nabonidus." Credit for that building project, however, was given instead to Nebuchadnezzar II and the Persian king Cyrus II, the last known builder of Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil.

Cyrus II's rebuilding of Imgur-Enlil and Babylon's embankment walls are recorded in that ruler's now-famous "Cyrus Cylinder." The relevant passage of that Akkadian text reads:

The seventh-century-BC Assyrian king Ashurbanipal, rather than any of the Babylonian kings whose walls were still standing when Cyrus entered Babylon in 539 BC, when he defeated its last native king, was chosen as the builder of Imgur-Enlil (and Nēmetti-Enlil). It is clear from the verbiage of the above-cited passage that the scribes who wrote out the building account of the "Cyrus Cylinder" were familiar with Nebuchadnezzar's inscriptions and were well aware of the building history of Babylon's city walls and embankments; for example, the mention of the embankment walls being incomplete is royal rhetoric copied directly from Nebuchadnezzar's texts rather than historical reality.

The imposing walls of Babylon, although nothing else is known about their building history after Cyrus II, were not soon forgotten. Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil were so impressive that they were regarded as one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, "along which chariots may race." It is clear from an Astronomical Diary entry for the year 123 BC that Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil, at least a portion of them, were still in use during the Seleucid and Parthian Periods.

Archaeological Remains

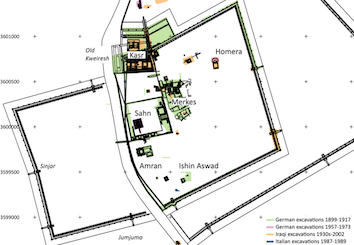

Annotated plan of Babylon showing the sections of the wall excavated by the Germans (green) and Iraqis (orange). Cropped from O. Pedersén, Babylon: The Great City, p. 15 fig. 1.4.

The substantive remains of Imgur-Enlil, Nēmetti-Enlil, and the embankment walls were partially excavated by the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft (DOG) and Königliche Museen Berlin (KMB) in 1899–1917 under the direction of Robert Koldewey and by Iraqi archaeologists in the 1970s and 1980s. The German team investigated long stretches of the walls in the eastern half of the city, especially in the northeastern and northwestern stretches, particularly in the area around the Ištar Gate and the South Palace, while the Iraqi teams exposed portions of Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil in and around the Marduk and Zababa Gates, along the eastern stretch of the inner city walls, as well as restored and reconstructed the Ištar Gate and the Marduk Gate. Only parts of the inner city wall surrounding East Babylon have been explored and the long stretches of the still-to-be-excavated parts of East Babylon are still visible on the ground and in modern satellite imagery. The walls and gates of West Babylon, however, have never been examined. The traces of the western circuit of Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil visible in a Corona satellite image from August 16th 1968 have now largely disappeared. The excavated remains of Babylon's once-towering inner city walls mostly come from the Neo-Babylonian Period, with some scant evidence from the earlier Neo-Assyrian Period (reign of Sargon II).

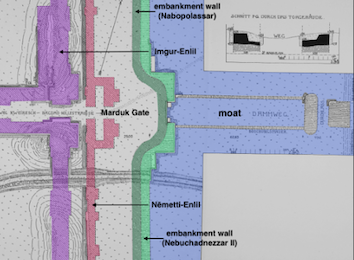

Annotated plan of the area around the Marduk Gate showing Imgur-Enlil (purple) and Nēmetti-Enlil (red), the embankment walls (green), and moat (blue). Adapted by Jamie Novotny from F. Wetzel, Die Stadtmauern von Babylon, pl. 35.

The Neo-Babylonian circuits of Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil followed the much-earlier-established rectangular plan of the inner city, one that was established by the Second Dynasty of Isin; this is inferred from the fact that two inscriptions of Adad-apla-iddina, including a brick mentioning Imgur-Enlil, were found in the vicinity of the Zababa Gate. Nearly all of the excavated remains of the inner city walls in East Babylon, apart from a small embankment wall dating to the reign of Sargon II, were built by Nabopolassar and Nebuchadnezzar II and their successors (principally Nabonidus). As described in royal inscriptions, and confirmed from the investigated portions of the walls, Babylon's inner city was surrounded by double mudbrick walls, Imgur-Enlil on the inside and Nēmetti-Enlil on the outside, embankment(s) (Akkadian kāru) of baked brick, and a moat (Akkadian hirītu). Access to the city was provided by eight gates, four entrances on each side; all four of the East Babylon gates have been excavated. These were also constructed of unbaked bricks; the Ištar Gate, starting in the time of Nebuchadnezzar II, was built from baked bricks and decorated with blue-glazed bricks. Bridges were built to cross the 80-m-wide moat.

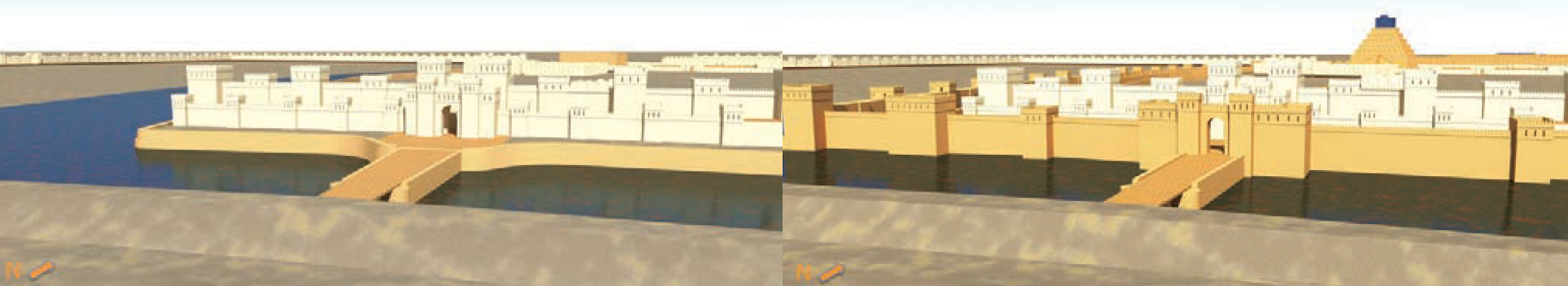

Digital reconstruction of Imgur-Enlil, Nēmetti-Enlil, and the embankment(s) in the area of the Uraš Gate during the reign of Nabopolassar (left) and the late reign of his son Nebuchadnezzar II or that of Nabonidus (right). Images from O. Pedersén, Babylon: The Great City, p. 45 figs. 2.10 and 2.12.

In the reign of Nabopolassar, the inner city was surrounded by only a single embankment; note that in the area of the South Palace, Nabopolassar had two embankments built. The main wall (Akkadian dūru) Imgur-Enlil and the outer wall Akkadian šalhû) Nēmetti-Enlil were respectively 6.5 m and 3.7 m thick, with estimated heights of 15 and 8 m. Alternating large and small towers were constructed at regular intervals. Nabopolassar's walls were completed and repaired several times by his son Nebuchadnezzar. That Neo-Babylonian king added a second embankment around the entire circuit of the inner city; thicker embankments were built in the area around the royal palace. As is clear from a few in-situ bricks in the massive, 7.6-m-thick embankment along the eastern bank of the Arahtu (the so-called "Nabonidus Wall"), as well as from a clay cylinder housed in a mudbrick box deposited in the structure of Imgur-Enlil near the Ištar Gate, work on the inner city walls continued throughout the Neo-Babylonian Period. It is estimated that a staggering 209,500,000 unbaked bricks and 384,600,000 baked bricks were used to build Babylon's walls and embankments. By far, this was the largest building complex in the city and, thus, it is little surprise that Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil were remembered long after Nebuchadnezzar transformed Babylon into a first-class imperial capital.

Further Reading

- Abdul-Razzak, W. 1979. "Ishtar gate and its inner wall," Sumer 35, pp. 112–117.

- Abdul-Razzak, W. 1985. "Ishtar gate and the inner wall," Sumer 41 pp. 19 and 22 [English Section] and pp. 34–35 [Arabic section].

- Damerji, M.S.B. 2012. "Babylon – ka.dingir.ra – 'gate of god': The story of a city killed by legends and oblivion," Mesopotamia 47, pp. 1–102.

- George, A.R. 1992. Babylonian Topographical Texts (Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 40), Leuven, pp. 13–29, 343–351, and 440–441.

- George, A.R. 2008. "Akkadian turru (ṭurru B) 'corner angle', and the walls of Babylon," Zeitschrift für Assyriologie 98, pp. 221–229.

- Kamil, A.M. 1979. "The inner wall of Babylon," Sumer 35, pp. 137–149.

- Kamil, A.M. 1985. "Excavation at the northeastern part of the inner wall," Sumer 41, pp. 20–21 [English section] and pp. 36–42 [Arabic section].

- Koldewey, R. 1931. Die Königsburgen von Babylon 1: Die Südburg (Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichung der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 54), Leipzig.

- Koldewey, R. 1932. Die Königsburgen von Babylon 2: Die Hauptburg und der Sommerpalast Nebukadnezars im Hügel Babil (Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichung der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 55), Leipzig.

- Koldewey, R. 1970. Das Ischtar-Tor in Babylon: nach den Ausgrabungen durch die Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft (Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 32), Osnabrück (Reprint of the 1918 edition).

- Koldewey, R. 19905. Das wieder erstehende Babylon, fifth edition (edited by B. Hrouda), Munich, pp. 129–132, 139–157, and 198–201.

- Pedersén, O. 2021. Babylon: The Great City, Münster, pp. 39–88.

- Wetzel, F. 1930. Die Stadtmauern von Babylon (Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichung der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 48), Leipzig.

Banner image: plan of Babylon with its walls and eight gates (left); annotated plan (right) of the area around the Marduk Gate excavated under the direction of Robert Koldewey (1899–1917) showing the inner and outer city walls (purple and red), the embankment walls (green), and moat (blue). Images adapted by Jamie Novotny from F. Wetzel, Die Stadtmauern von Babylon, pl. 35.; and O. Pedersén, Babylon: The Great City, p. 43 fig. 2.2.

Jamie Novotny

Jamie Novotny, 'Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil (inner city walls of Babylon)', Babylonian Temples and Monumental Architecture online (BTMAo), The BTMAo Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, [http://oracc.org/btmao/Babylon/WallsandGates/InnerCityWalls/]