Nineveh

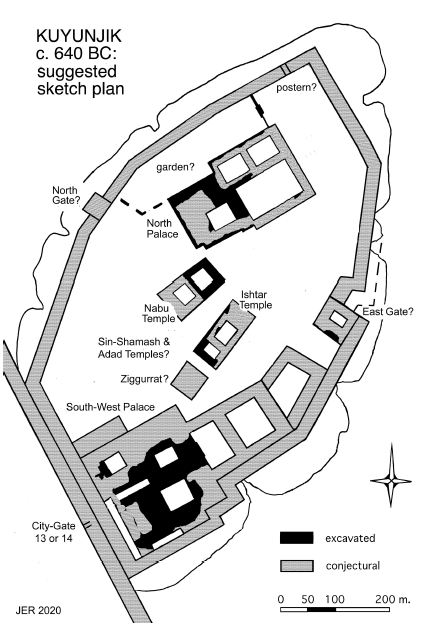

Figure 6. Plan of Kuyunjik ca. 640. Drawing by J.E. Reade, 2020. Reproduced courtesy of J.E. Reade.

Ashurbanipal spent much of his youth in Nineveh (modern Kuyunjik and Nebi Yunus), the city that his grandfather Sennacherib had transformed into the leading metropolis of Assyria,[36] in particular in the House of Succession (bīt ridûti), where he was not only trained in the scribal arts, but also in the precepts of kingship after he was officially designated as heir designate in early 672.[37] Ashurbanipal's fondness for the palace where he was (born and) raised and for his (birth) city,[38] as well as the fact that the city had been Assyria's principal administrative center since the beginning of his grandfather's reign, ensured that Nineveh's palaces, temples and city walls would not be neglected or fall into disrepair. Extant inscriptions, as well as archaeological evidence, demonstrate that Nineveh continued to thrive and remained Assyria's pre-eminent city throughout the duration of Ashurbanipal's long reign. At the present time, he is known to have (re)built, enlarged, renovated, and/or decorated the following structures in the citadel and lower town: the House of Succession (bīt ridûti), together with a shrine dedicated to the goddess Bēlet-parṣē; Egalzagdinutukua ("Palace Without a Rival"; = Sennacherib's palace, also known today as the South-West Palace); Emašmaš ("House in Which Divination Is Performed"), the temple of Ištar/Mullissu, and its ziggurat (temple-tower) Ekibikuga ("House, Pure Abode"); Ezida ("True House"), the temple of the god Nabû; the Kidmuri temple; the double Sîn-Šamaš temple; one of the akītu-houses; the citadel wall, and the armory (referred to as the "Rear Palace" [ekal kutalli] and the "Review Palace" [ekal māšarti]).[39]

The biggest, as well as longest, project undertaken by Ashurbanipal was the construction of his own palace, the House of Succession (bīt ridûti).[40] Work began on the North Palace, as it is often referred to by modern scholars, early in his reign (probably in or before 666/665) and it was completed sometime between his 25th (644) and 28th (641) regnal years.[41] The bulk of the prisms deposited in its structure were inscribed ca. 645–642, so it appears that the king made a concerted effort around that time to finish the work on his new royal residence.[42] Having fond memories of the palace in which he was raised and educated, Ashurbanipal decided to build a bigger and better House of Succession on the site of the old one, in the northeastern part of the citadel. Before construction could begin, the massive mud-brick structure of the former palace, as well as the brick platform beneath it, had to be completely removed; undoubtedly, this Herculean task took a great deal of time and effort, requiring a large workforce. Once the building site had been prepared, workmen raised the height of the terrace by fifty courses of brick (ca. 6–7 m, depending on the thickness of the bricks and mortar); out of respect for the neighboring temples, the terrace was not raised any higher. In consultation with specialists, the (stone) foundations were laid in a favorable month, on an auspicious day. After that, construction of the superstructure began. The most detailed account of the project, the account known from the now-famous "Rassam Prism" (text no. 11 [Prism A] ex. 1), which was found intact in one of the walls of Room H, records this stage as follows:

Once the sun-dried brick walls had been raised to their intended height, the palace was roofed with long beams of cedar (transported all the way from the Levant), metal-banded doors of variety of white cedar (liāru) were hung in its principal gateways, and the lower parts of some of the rooms were decorated with sculpted (and inscribed) limestone slabs depicting a wide range of topics; scenes of war (and the aftermath of successful battles and sieges) and the hunting of lions were particular favorites.[44] In addition, Ashurbanipal had an elaborate pillared portico, a bīt ḫilāni (also called a bīt appāte in inscriptions of Sargon II and Sennacherib), and a shrine dedicated to the goddess Bēlet-parṣē built, as well as having a lush botanical garden planted next to the palace.[45] Ashurbanipal's palace rivaled that of his predecessors.

Ashurbanipal's grandfather had built himself a magnificent palace on the southwestern part of the citadel, Egalzagdinutukua, whose Sumerian ceremonial name means the "Palace Without a Rival" and which truly lived up to its name.[46] The "Alabaster House," as it was sometimes called, continued to be used as an administrative center by Ashurbanipal and his successors and, therefore, it was regularly maintained.[47] Although no inscriptions of Ashurbanipal record the upkeep or alterations that he had made to the South-West Palace (a modern designation given to the building), it is clear from the archaeological record that some changes were made to the grand, ornately-decorated royal residence of Sennacherib. These included: (1) the walls of Room XXIII were redecorated with an exquisite series of bas reliefs depicting the battle of Tīl-Tūba and its aftermath; (2) Ashurbanipal paving stones were found on the southwestern side of Court H; (3) Room XXII was partially redecorated with scenes of the landscape around Nineveh and a triumphal procession of men wearing foliage on their heads; (4) the walls of Court XIX and Room XXVIII were recarved with scenes of warfare in southern Babylonia (Chaldea); and (5) the wall panels in Room XLII and Court XLIX had their former images scraped clean in order to be recarved with new images.[48]

Throughout the first half of his reign, Ashurbanipal had (sections of) the citadel wall (dūr qabal āli) rebuilt, renovated, or repaired on account of water damage and/or old age.[49] The lowest courses, especially those that were nearest to the Tigris and Khosr rivers on the southern and western sides, were reinforced with large, hard ashlar blocks (hewn from the mountains). The mud-brick superstructure was reportedly made wider. The East Gate, which had the ceremonial Akkadian name "Entrance to the Place Where the World Is Controlled" (nēreb masnaqti adnāti), might have also been rebuilt or renovated, not only because it was the principal entrance to the citadel, but also because it was a favorite spot to humiliate recalcitrant foes (for example, the Arabian king Uaiteʾ, who was chained up there like a dog).[50] As an important landmark, which played a key role in the political and religious life of the city, it was vital that the East Gate was always kept in good repair and, therefore, despite the lack of textual evidence, it would be surprising if it had not received attention while Ashurbanipal was king.

Many of Nineveh's temples were renovated and/or enlarged during Ashurbanipal's long tenure as king. Inscriptions record or allude to work on seven of them.[51] Inscriptions often mention that he had the walls of Emašmaš ("House in Which Divination Is Performed"), the temple of Ištar/Mullissu, lavishly decorated with gold and silver; the texts themselves provide no details about the type of objects presented to and/or commissioned for the temple of Nineveh's tutelary goddess.[52] Late in his reign, ca. 645–638, Ashurbanipal reinforced the structure of Emašmaš with large ashlar blocks, enlarged its courtyard and had it repaved with inscribed limestone slabs, and had its (principal) gateway(s) lavishly outfitted with silver and gold(-plated) door jambs and door bolts.[53] In her manifestation as the planet Venus (Dilbat), Ashurbanipal had a star emblem (kakkabtu) dedicated to Ištar after the rebellious and difficult-to-catch Arabian king Uaiteʾ had been captured; this might have been displayed in Emašmaš or in her akītu-house (see below).[54] Work was also carried out on Nineveh's ziggurat, Ekibikuga ("House, Pure Abode") and Ištar/Mullissu's processional boat Matummal while he was working on Emašmaš.[55] Unfortunately, little is known about these two projects since the only extant report about them is badly damaged. With regard to Matummal, Ashurbanipal had it made of cedar and decorated with silver. As for the ziggurat, the relevant details are completely missing, so it is not yet possible to state with any degree of accuracy the nature of the work undertaken on it by Ashurbanipal's workmen.

Around Ashurbanipal's 24th regnal year (645), one of the akītu-houses of Ištar/Mullissu was completely rebuilt and sumptuously decorated.[56] At that time, there were two New Year's temples at Nineveh:[57] (1) Ešaḫulezenzagmukam ("House of Joy for the Festival of the Beginning of the Year"), which Sennacherib had started building north of the Nergal Gate, but never finished;[58] and (2) the former, original akītu-house, which was located within the citadel and which had last been rebuilt by Sargon II.[59] Ashurbanipal worked on the latter. He boasts that he had the new building decorated with glazed baked bricks depicting representations of defeated settlements and foes; presumably the images were accompanied by epigraphs.[60] After its completion and after the capture of several recalcitrant Arabian and Elamite kings (Paʾê, Tammarītu, Uaiteʾ, and Ummanaldašu [Ḫumban-ḫaltaš III]), Ashurbanipal celebrated an akītu-festival during the month Ṭebētu (X), during which Paʾê, Tammarītu, Uaiteʾ, and Ummanaldašu (Ḫumban-ḫaltaš III) were hitched up to the king's processional carriage like horses and made to transport Ashurbanipal between Emašmaš and the New Year's temple.[61]

Ca. 645–638, while work was being carried out on Emašmaš, Ashurbanipal had the courtyard of Ezida ("True House") enlarged and paved with inscribed limestone slabs, as well as having its cella (atmanu) lavishly decorated with silver and gold.[62] To commemorate the defeat of the Elamite king Ummanaldašu (Ḫumban-ḫaltaš III), the sack of Susa, and the return of a statue of the goddess Nanāya to Uruk, events that took place in his 23rd regnal year (646), Ashurbanipal had an inscribed, reddish gold knife (makkas ḫurāṣi ruššî) fashioned and dedicated to Nabû.[63] Presumably other metal objects were made for this Ezida temple, but information about them is not recorded or mentioned in extant inscriptions.

Several inscriptions record that Ashurbanipal had the image of Šarrat-Kidmuri refurbished and reinstalled on her dais and had her cultic ordinances and rites reinstituted, since they had been discontinued when the goddess' cult statue had been removed in order to be repaired.[64] It appears that a previous king had Šarrat-Kidmuri's image removed from her temple, likely to have it repaired, but the work was never completed and, thus, the image had not been returned to its rightful place. Once the proper divine approval had been granted, specifically after receiving a positive response to a haruspical query to the gods Šamaš and Adad, the refurbishment of Šarrat-Kidmuri's image was completed, the goddess was ceremoniously returned home, and her abandoned rites and rituals were restored.

Like Sennacherib and Esarhaddon, Ashurbanipal also rebuilt the Sîn-Šamaš temple, a double temple whose exact location is still not known and whose Sumerian ceremonial name is not recorded in extant cuneiform sources.[65] Work on this building appears to have taken place between 648 and 646.[66] When the temple was completed, the statues of Sîn, Nikkal (Ningal), Šamaš, Aya, and Nusku were returned to their daises. Virtually nothing about the decoration of the temple is recorded in Ashurbanipal's inscriptions; however, Nusku's image seems to have been refurbished around 645. The image was inscribed with a text commemorating the events of the fifth Elamite campaign (= Elam 6).[67]

Lastly, Ashurbanipal is known to have made repairs to the armory, a large, multi-winged palatial complex located in the lower town, south of the citadel, near the western city wall.[68] His workmen renovated the part of the building that Sennacherib had constructed, as well as the extension that Esarhaddon had added.[69] Few details about the project are recorded in extant texts and most of what is stated consists of stock phrases referring to building a structure completely from top to bottom and better than previously. Inscribed wall slabs and a human-headed bull colossus attest to Ashurbanipal's work on this palace.[70]

Notes

[36] For details on Sennacherib's many building activities at Nineveh, see in particular Grayson, CAH2 3/2 pp. 113–116; Frahm, Sanherib pp. 267–276 and passim; Reade, RLA 9/5–6 (2000) pp. 388–433, esp. §§11, 13.1, 13.5–6, 14.2–3, 15.2, 15.4, and 15.8; Frahm, PNA 3/1 pp. 1121–1122 sub Sīn-aḫḫē-erība II.3c-1´; Frahm, RLA 12/1–2 (2009) p. 19 §6.1.1–8; Grayson and Novotny, RINAP 3/1 pp. 16–22; and Grayson and Novotny, RINAP 3/2 p. 18.

[37] For details, see in particular Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 pp. 13–14 (with textual references and bibliography).

[38] Ashurbanipal's place of birth is not recorded in extant cuneiform sources, but it is tentatively assumed here that he was born in Nineveh, in the House of Succession, just like his father Esarhaddon, who is said to have been born in that palace; see Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 192 no. 9 (Prism F) i 20–21a and p. 231 no. 11 (Prism A) i 27–28a.

[39] Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 pp. 41–42 no. 1 (Prism E₁) vii 1´–8´, p. 51 no. 2 (Prism E₂) vii 4´–8´, pp. 58 and 78–79 no. 3 (Prism B) i 16–21 and viii 56–69, pp. 83 and 99 no. 4 (Prism D) i 14–17 and viii 58–74, pp. 105–106 no. 5 (Prism I) iv 9–27, pp. 114 and 135 no. 6 (Prism C) i 48´–61´ and x 19´´–2´´´, p. 139 no. 7 (Prism Kh) i 18´–34´, pp. 205–207 no. 9 (Prism F) vi 22–61, pp. 216–218 and 220 no. 10 (Prism T) ii 7–24, iii 18–35a and v 33–49, pp. 262–263 no. 11 (Prism A) x 51–108a, p. 291 no. 21 line 5´, pp. 301–302 and 310 no. 23 (IIT) lines 30–40a and 162–166a, pp. 351–352 no. 59 (Nabû Inscription) lines 12b–14a, and pp. 353–354 no. 60 (Mullissu Inscription) lines 12b–14a; and, in this volume, no. 86 iv 1´´–14´´, no. 92 v 5–6, no. 97 rev. ii´ 1´–6´, no. 115 lines 8–14, no. 154 lines 11´–rev. 3, no. 155 rev. 15–18, no. 159 lines 5b–18a, no. 160 rev. 2b–7a, no. 215 (Edition L) i 30´–37´ and left edge 1–2. For details about most of the building discussed here, see also Reade, RLA 9/5–6 (2000) pp. 388–433, esp. §§11, 13.1, 13.3, 13.5–6, 14.1–7, and 15.1–2.

[40] Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 pp. 41–42 no. 1 (Prism E₁) vii 1´–8´, pp. 205–207 no. 9 (Prism F) vi 22–61, and pp. 262–263 no. 11 (Prism A) x 51–108a; and, in this volume, no. 86 iv 1´´–14´´, no. 92 v 5–6, and no. 97 rev. ii´ 1´–6´. For information on the North Palace, see, for example, Barnett, Sculptures from the North Palace; Kertai, Architecture of Late Assyrian Royal Palaces pp. 167–184 and passim; Reade, RLA 9/5–6 (2000) pp. 416–418 §14.4 and 14.7; Reade in Brereton, I am Ashurbanipal pp. 20–33; J.M. Russell, Writing on the Wall pp. 154–209; and Reade, Design and Destruction. Only a fraction (less than half) of the once-opulent House of Succession has been excavated. The principal floor level was not far below the modern surface of the Kuyunjik mound, and (substantial) portions of the palace have been destroyed by erosion and later occupation phases. On its size, J.E. Reade (in Brereton, I am Ashurbanipal p. 22) has stated: "The ground plan of the palace seems to have measured at least 100 by 200 metres, but it could have been far larger. The exact limits are conjectural: only the grandest part of the palace, on its western side, over 100 metres square or perhaps 200 Assyrian royal cubits, was exposed and planned during the excavations." Elsewhere, Reade (RLA 9/5–6 p. 418) has given the dimensions of the building as "at least 125 m from north-west to south-east and 250 m from north-east to south-west."

[41] J. Reade (RLA 9/5–6 [2000] p. 417 §14.7) has suggested that the North Palace was likely completed ca. 643. It is possible that work on that impressive royal residence came to an end shortly after Reade's proposed date, either in 642 or in 641. In any event, there is no reason to assume that the construction of the House of Succession had not been completed by 640, Ashurbanipal's 29th year on the throne.

[42] These prisms bear text nos. 9 (Prism F) and 11 (Prism A), which were inscribed on these multi-faceted clay objects during the eponymies of Nabû-šar-aḫḫēšu and Šamaš-daʾʾinanni respectively.

[43] Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 263 no. 11 (Prism A) x 83–97.

[44] Some of the carefully-executed reliefs had epigraphs (short inscriptions and labels) carved on them. At present, only twenty-five epigraphs have been discovered in various rooms of the North Palace (Rooms F, I, M, S¹, and V¹/T¹). For details, as well as references to previous scholarly literature, see Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 pp. 5–6. One poorly preserved epigraph from Room XXXIII was overlooked in the edition of the epigraphs; see Reade, NABU 2000 p. 88 no. 78 (81-2-4,5), which reads [... LU]GAL-u-t[i ...] / [... d]a-na-an [...] / [...]-áš TAR-[...] / [... az-qu?]-⸢pa? ṣe?⸣-[ru-uš-šú? (...)].

[45] Ashurbanipal had at least two metal(-plated) and inscribed objects made for Bēlet-parṣē: an arattû-throne and another item which cannot be identified due to the poor state of preservation of the inscription recording its construction; see text nos. 159–160.

[46] Reade, RLA 9/5–6 (2000) pp. 411–416 §§14.2–3; and Grayson and Novotny, RINAP 3/1 p. 17. For a detailed and comprehensive study of the "Palace Without a Rival" (the South-West Palace), see J.M. Russell, Senn.'s Palace. For information on the palace reliefs, see Barnett et al., Sculptures from the Southwest Palace; Lippolis, Sennacherib Wall Reliefs; and J.M. Russell, Final Sack.

[47] For details, see Reade, RLA 9/5–6 (2000) p. 415 §14.3.

[48] Some of these changes might have taken place during the reign of Sîn-šarra-iškun, since one of his inscriptions records that he had the western part of the palace renovated.

[49] Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 51 no. 2 (Prism E₂) vii 4´–8´ and p. 99 no. 4 (Prism D) viii 58–69. From the concluding formula of text no. 8 (Prism G), the buildingreport of that annalistic text would have also recorded the construction of the citadel wall; see Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 178 no. 8 (Prism G) x 8´´. The work mentioned in those inscriptions was carried out ca. 665–664 and 648–646. It is fairly certain that Ashurbanipal's workmen discovered inscriptions of Sennacherib buried in the structure of that wall; an archival copy of that inscription, which was written on either clay cylinders or clay prisms, is known from K 2662+ (Grayson and Novotny, RINAP 3/2 pp. 7–8 and 170–179 Sennacherib 136–139).

[50] Ashurbanipal's father and grandfather are known to have undertaken similar actions. Sennacherib states that he bound the defeated king of Babylon Šūzubu (Nergal-ušēzib) together with a bear, while Esarhaddon claims to have chained Asuḫīli, the king of Arzâ, in that gate with a bear, a dog, and a pig. See Grayson and Novotny, RINAP 3/1 p. 223 Sennacherib 34 (Nebi Yunus Inscription) lines 34–35; and Leichty, RINAP 4 pp. 17–18 Esarhaddon 1 (Nineveh A) iii 39–42.

[51] For an overview of the temples at Nineveh, see Reade, RLA 9/5–6 (2000) pp. 407–410 §§13.1–8.

[52] Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 58 no. 3 (Prism B) i 16–21, p. 83 no. 4 (Prism D) i 14–17, p. 114 no. 6 (Prism C) i 48´–49´, p. 139 no. 7 (Prism Kh) i 18´–20´, p. 216 no. 10 (Prism T) ii 7–8, and p. 291 no. 21 line 5´. For some details on Emašmaš (also called Emesmes and Emešmeš in cuneiform sources), see, for example, George, House Most High pp. 121–122 no. 742; Reade, RLA 9/5–6 (2000) pp. 407–409 §13.1; and Reade, Iraq 67/1 (2005) pp. 347–390.

[53] Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 pp. 301 and 310 no. 23 (IIT) line 30 and 162–166a and pp. 353–354 no. 60 (Mullissu Inscription) lines 12b–14a. Numerous inscribed paving stones attest to Ashurbanipal's claim to have enlarged and paved the courtyard of Emašmaš; see Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 pp. 352–354 no. 60 (Mullissu Inscription) for further details.

[54] Text no. 156 rev. 13–20.

[55] Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 pp. 301–302 no. 23 (IIT) lines 35b–37a. For a brief overview of the long history of Ekibikuga, which is generally referred to as Ekituškuga in ancient textual sources, see George, House Most High p. 112 no. 630.

[56] Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 220 no. 10 (Prism T) v 33–49 and p. 301 and no. 23 (IIT) lines 31–35a. It is uncertain when the project began and ended. By the composition of text no. 10 (Prism) in the eponymy of Nabû-šar-aḫḫēšu (645), the work was underway. By the time text no. 11 (Prism A) was composed in the eponymy of Šamaš-daʾʾinanni (possibly 643, but 644 and 642 are also possible), construction of the akītu-house appears to have come to an end since Ashurbanipal performed a New Year's festival in it.

[57] For evidence that there were two akītu-houses at Nineveh, see Frahm, NABU 2000 pp. 75–79 no. 66, as well as Grayson and Novotny, RINAP 3/1 p. 22.

[58] Frahm, JCSMS 3 (2008) p. 17.

[59] A fragmentary inscription on a limestone block found by R. Campbell Thompson at Nineveh, between the Ištar and Nabû temples, and currently in the British Museum, might be inscribed with an inscription of Sargon II recording the renovation of Ištar's New Year's temple; for an edition of that text, see Frame, RINAP 2 p. 478 Sargon II 1007.

[60] Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 301 no. 23 (IIT) lines 32b–35a, states: "I now built (and) co[mp]leted (it) in its entirety [with baked bricks inlai]d with obsidian (and) lapis lazuli. I filled (it) with splendor. Through the craft of the deity Ninzadim, I depi[ct]ed on it (images of) the settlements of enemies that I had co[nq]uered (and) representations of en[e]mies who(se defeat) I had regularly brought about by the command of her exalted d[ivini]ty, as well as (those of) kings who had not bowed d[own] to me." Glazed bricks showing scenes of battle are attested for the Neo-Assyrian period, for example, depicting Esarhaddon's Egyptian campaigns. For details, see in particular Fügert and Gries in Fügert and Gries, Glazed Brick Decoration pp. 28–47; Lehmann and Tallis, Esarhaddon in Egypt; Lehmann and Tallis inFügert and Gries, Glazed Brick Decoration pp. 85–95; and Nadali, Iraq 68 (2006) pp. 109–119. Note that one glazed brick with an epigraph of Ashurbanipal, reportedly from Nebi Yunus, is known; see Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 pp. 366–367 no. 71. Given the available archaeological evidence, there is no reason to doubt the validity of Ashurbanipal's claims regarding the decoration of the akītu-house at Nineveh.

[61] For example, see Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 261 no. 11 (Prism A) x 17–39.

[62] Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 302 no. 23 (IIT) lines 37b–38a and pp. 351–352 no. 59 (Nabû Inscription) lines 12b–14a. Numerous inscribed paving stones attest to Ashurbanipal's claim to have enlarged and paved the courtyard of Ezida. Text no. 23 (IIT) line 37b seems to imply that work on Ezida began only after work on Emašmaš had been completed. For brief overviews of this temple, see George, House Most High p. 160 no. 1238; and Reade, RLA 9/5–6 (2000) p. 410 §13.5.

[63] Text no. 155. The knife is said to have weighed five minas.

[64] Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 114 no. 6 (Prism C) i 50´–61´, p. 139 no. 7 (Prism Kh) i 21´–34´, and p. 216 no. 10 (Prism T) ii 9–24; and, in this volume, no. 115 lines 8–14 and no. 215 (Edition L) i 33´–37´ and left edge 1–2. For some details on the Kidmuri temple at Nineveh, see Reade, RLA 9/5–6 (2000) pp. 409–410 §13.3. It is possible that Egašanḫilikuga ("House of the Lady of Pure Luxuriance"), which is mentioned in text nos. 72 (i 2´) and 191 (obv.? 13), is the Sumerian ceremonial name of the Šarrat-Kidmuri temple/cella at Nineveh, as tentatively suggested by J. Novotny (Eḫulḫul pp. 215–217).

[65] Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 pp. 105–106 no. 5 (Prism I) iv 9–27, pp. 217–218 no. 10 (Prism T) iii 18–35a, and p. 302 no. 23 (IIT) lines 38b–40a; and, in this volume, no. 154 lines 11´–rev. 3. For a brief overview of the temple, see Reade, RLA 9/5–6 (2000) p. 410, esp. §13.6.

[66] The earliest attested mention of the project is V-8-648 (Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 107 no. 5 [Prism I] v 35–36 [ex. 4]), presumably when the project was already underway. Construction might have been completed by V-6-645 (Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 221 no. 10 [Prism T] vi 52B–54B [ex. 2]) since the earliest extant copy of text no. 10 (Prism T) includes a description of the rebuilding of the Sîn-Šamaš temple in its prologue.

[67] Text no. 154.

[68] Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 78 no. 3 (Prism B) viii 56–69, p. 135 no. 6 (Prism C) x 19´´–2´´´, and pp. 359–360 no. 64. The building, which is buried within the small mound now called Nebi Yunus ("Prophet Jonah") and which is referred to as the "Rear Palace" (ekal kutalli) and occasionally as the "Review Palace" (ekal māšarti) in Neo-Assyrian inscriptions, has an important Muslim shrine on top of it and therefore has not been fully explored or excavated. According to tradition, as the name of the mound suggests, Jonah was buried there; when the tomb of Ḥnanīšō was opened in 1349, the body inside was identified as that prophet. Parts of the site, mostly along the edges of the mound, however, have been exposed and explored. For further information, see Reade, RLA 9/5–6 (2000) pp. 419–420 §15.2; Grayson and Novotny, RINAP 3/1 pp. 21–22; Reade, Studies Postgate pp. 431–458; al-Juboori, Iraq 79 (2017) pp. 3–20; Robson, Sumer 64 (2018) pp. 73–98; and Maul and Miglus, ZOrA 13 (2020) pp. 218–213.

[69] The building report of Prism B (text no. 3) recorded work on the part of the armory that Sennacherib had had constructed on the site of the previous arsenal and that of Prism C (text no. 6), which is now almost completely missing, described the rebuilding of the wing that Esarhaddon had built onto the armory erected by Sennacherib.

[70] al-Juboori, Iraq 79 (2017) pp. 11–12; Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 pp. 359–360 no. 64; and Maul and Miglus, ZOrA 13 (2020) pp. 191–192.

Jamie Novotny

Jamie Novotny, 'Nineveh', RINAP 5: The Royal Inscriptions of Ashurbanipal, Aššur-etel-ilāni, and Sîn-šarra-iškun, The RINAP/RINAP 5 Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, 2022 [http://oracc.org/rinap/rinap5/rinap52introduction/buildingactivitiesinassyria/nineveh/]