Kalḫu

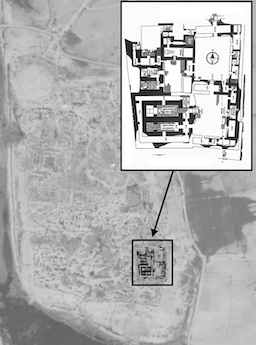

Figure 9. Satellite image of the citadel of Kalḫu with a plan of Ezida, the temple of the god Nabû. The plan of Ezida is reproduced from Oates and Oates, Nimrud p. 112 fig. 67.

Despite the fact that Kalḫu (modern Nimrud) ceased to be the principal administrative center of the Assyrian Empire after Ashurbanipal's great-grandfather Sargon II moved the capital to the newly-constructed Dūr-Šarrukīn (modern Khorsabad), that city still played in important role until Assyria ceased to exist as a political entity.[85] The temple of the god Nabû, Ezida ("True House"), remained a vital part of Assyria's cultic topography, which is clear from the fact that it was regularly rebuilt and renovated in the seventh century.[86] Ashurbanipal, as known from the building report of an annalistic text inscribed on decagonal clay prisms deposited inside the walls of that temple, had Ezida, or at least part of it, rebuilt.[87] Although the king boasts of having "built and completed (it) from its foundation(s) to its crenellations," the full extent of the work is unknown. Despite Ashurbanipal's claims, which might owe more to royal ideology than historical reality, it appears that only part of Ezida was renovated during Ashurbanipal's third decade as king.[88] The rooms renovated by him are reported to have been roofed with beams of cedar (presumably from the Levant) and had its copings decorated; the nature/type of the decoration is not mentioned.

Ashurbanipal very likely undertook other building activities at Kalḫu, but these projects are not recorded in extant inscriptions of his and, therefore, not discussed here.[89]

Notes

[85] For information on Kalḫu, see in particular Oates and Oates, Nimrud; and the open-access, Oracc-based Nimrud: Materialities of Assyrian Knowledge Production website (oracc.org/nimrud [last accessed April 11, 2022]).

[86] For an overview of the building history of the Ezida temple at Kalḫu, see George, House Most High p. 160 no. 1239; and Novotny and Van Buylaere, Studies Oded pp. 215–219 (esp. p. 218). For a discussion of the archaeological remains of that temple, see, for example, D. Oates, Iraq 19 (1957) pp. 26–39 and pl. XII; and Oates and Oates, Nimrud pp. 111–119.

[87] Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 164 no. 7 (Prism Kh) x 53´–64´. For the find spots of the prism fragments, see the catalogue of texts on pp. 136–137 of that book.

[88] It is possible that Ashurbanipal, as well as his two sons Aššur-etel-ilāni and Sîn-šarra-iškun, only worked on the southern part of Ezida, the wing of the temple renovated by Adad-nārārī III (810–783).

[89] For example, the so-called "Town Wall Palace of Ashurbanipal" (Oates and Oates, Nimrud pp. 141–143). The clay bird's head inscribed with the name of Assurbanipal discovered under the floor of the west building has never been published. Its current whereabouts are unknown, but it is likely in the Iraq Museum (Baghdad).

Jamie Novotny

Jamie Novotny, 'Kalḫu', RINAP 5: The Royal Inscriptions of Ashurbanipal, Aššur-etel-ilāni, and Sîn-šarra-iškun, The RINAP/RINAP 5 Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, 2022 [http://oracc.org/rinap/rinap5/rinap52introduction/buildingactivitiesinassyria/kalhu/]