Aššur

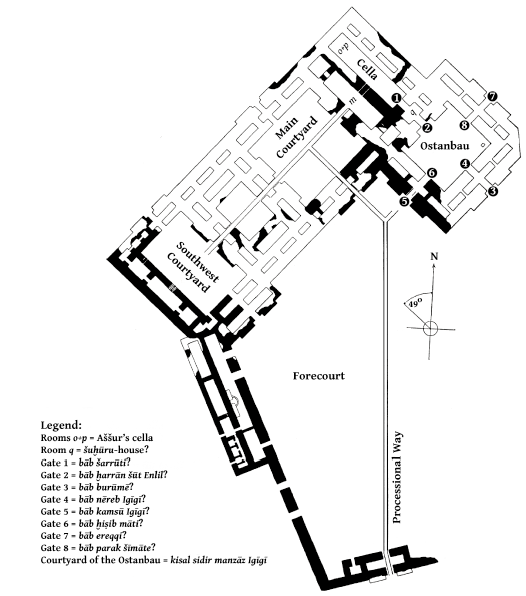

Figure 7. Plan of the Aššur Temple. Adapted from Andrae, WEA2 p. 53 fig. 35.

In Araḫsamna (VIII) 669, Esarhaddon died.[71] At the time of his death, many construction projects in Assyria, as well as in Babylonia, including work on the kingdom's most important building, the temple of the national god Aššur at Aššur (modern Qalʿat Širqāt), remained unfinished.[72] It fell upon his successors, Ashurbanipal in Assyria and Šamaš-šuma-ukīn in Babylonia, to complete these important endeavors.[73] Shortly after ascending the throne, or so it is assumed, Ashurbanipal had the holiest temple in his kingdom, the Aššur temple Ešarra ("House of the Universe"), together with its cella (Eḫursaggalkurkurra; "House of the Great Mountain of the Lands"), completed.[74] Despite the fact that Esarhaddon claims on several occasions to have finished rebuilding and lavishly decorating Aššur's temple, returned the god's statue to its rightful place on its newly-built and improved dais (the Dais of Destinies), and publicly celebrated this major accomplishment,[75] the completion of Ešarra, especially Eḫursaggalkurkurra, the final decoration of its interior, and the return of Aššur to the temple actually took place after Ashurbanipal ascended the throne in late 669.[76] In addition to completing the construction of the temple's structure and adorning its walls with gold and silver decorations (details not recorded), Ashurbanipal had two (inscribed) silver-banded wooden columns (timmu) erected in the Gate of the Abundance of the Lands (bāb ḫiṣib māti)[77] and a variety of metal(-plated) objects, including a processional carriage (ša šadādi), made for Aššur. The (metal-plated) processional carriage was dedicated to Aššur after Assyrian troops and their allies (from the Levantine coast and Cyprus) defeated Taharqa, the pharaoh of Egypt, and sacked and looted Thebes; the metal upon which an inscription commemorating the event was engraved likely came from the vast quantities of metal brought back to Nineveh in 664.[78] Presumably, other inscribed objects were gifted to Aššur during Ashurbanipal's long tenure as king, but no records of these objects are presently extant.

A copy of an inscription known from a badly-damaged stone tablet that was later reused as a door socket records that Ashurbanipal repaired or rebuilt (part of) Aššur's city wall.[79] The only-preserved record of that project, which was completed or still in underway in 655, reads as follows:

Afterwards, Ashurbanipal claims to have returned inscribed objects of his predecessors that his workmen had discovered during the project, specifically steles, and set them up along his own monuments.

Notes

[71] Grayson, Chronicles p. 86 no. 1 iv 30–31 and p. 127 no. 14 lines 28´–30´.

[72] Inscriptions of Ashurbanipal regularly refer to this. For example, Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 111 no. 6 (Prism C) i 5´–10´: "(As for) the sanctua[ries of A]ssyria (and) the land Akkad whose foundation(s) Esarh[addon], king of Assyria, the father who had engendered me, had laid, but whose construction he had not finished, I myself now completed their work by the command of the great gods, my lords."

[73] Completing the unfinished projects of Esarhaddon in Babylonia, particularly in Babylon, was the responsibility of Šamaš-šuma-ukīn, the king of Babylon; however, Ashurbanipal took it upon himself to complete a few of those in-progress building activities, including the reconstruction of Esagil ("House Whose Head Is High"), the temple of the god Marduk, and the ziggurat Etemenanki ("House, Foundation of Heaven and Netherworld"). These actions might have contributed to creating a rift between the two brothers, eventually leading Šamaš-šuma-ukīn to rebel against Ashurbanipal in 652. For an overview of the Šamaš-šuma-ukīn rebellion (with references to earlier scholarly literature), see Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 pp. 22–23.

[74] For information on the Aššur temple, see, for example, Börker-Klähn, ZA 70 (1980) pp. 258–273; van Driel, Aššur pp. 1–50; George, House Most High pp. 101–102 no. 486; Grayson and Novotny, RINAP 3/2 pp. 20–22; Gries, Assur-Temple; Haller, Heiligtümer pp. 52–73; Frahm, Sanherib pp. 163–173 and 276; Frahm, PNA 3/1 p. 1122 sub Sīn-aḫḫē-erība II.3.c.2´.a´; Galter, Orientalia NS 53 (1984) pp. 433–441; Huxley, Iraq 62 (2000) pp. 109–137; Novotny, JCS 66 (2014) pp. 91–112; Pongratz-Leisten, Ina Šulmi Īrub pp. 60–64; and Schwenzner, AfO 7 (1931–32) pp. 239–251, AfO 8 (1932–33) pp. 34–45 and 113–123, and AfO 9 (1933–34) pp. 41–48. According to the Götteradressbuch (George, BTT pp. 176–179 no. 20 lines 144–146; BTTo Götteradressbuch of Ashur Recension A lines 1–3 [oracc.org/btto/Q004802; last accessed April 11, 2022]), Ešarra ("House of the Universe") was the entire temple, Eḫursaggalkurkurra was the cella, and Eḫursaggula was the šuḫūru-house. Some inscriptions of Ashurbanipal (for example, Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 212 no. 10 [Prism T] i 14–20) give the impression that Eḫursaggalkurkurra was the main temple and that Eḫursaggula was the cella.

[75] For example, see Leichty, RINAP 4 pp. 127–128 Esarhaddon 57 (Aššur A) vi 1–vii 12: "I built (and) completed that temple from its foundations to its parapets (and) filled (it) with splendor to be seen. ... I restored the shrines, daises, cult platforms, (and) ruined ground plans; I made (them) good and made (them) shine like the sun. Its top was high (and) reached the heavens; below, its foundations were entwined with the apsû. I made anew whatever furnishings were needed for Ešarra and put (them) in it. I had the god Aššur, king of the gods, dwell in his lordly, sublime chapel on (his) eternal dais (and) I placed the gods Ninurta, Nusku, (and all of) the gods (and) goddesses in their stations to the right and left. I slaughtered a fattened bull (and) butchered sheep; I killed birds of the heavens and fish from the apsû, without number; (and) I piled up before them the harvest of the sea (and) the abundance of the mountains. The burning of incense, a fragrance of sweet resin, covered the wide heavens like heavy fog. I presented them with gifts from the inhabited settlements, (their) heavy audience gift(s), and I gave (them) gifts." As for the Dais of Destinies (parak šīmāte), Esarhaddon (Leichty, RINAP 4 p. 136 Esarhaddon 60 lines 26´–29´a) records that he entirely rebuilt it with ešmarû-metal and had images of both him and his son Ashurbanipal (then heir designate) depicted on its outer facing. For further details, see Grayson and Novotny, RINAP 3/2 pp. 21–22 (esp. n. 56).

[76] Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 58 no. 3 (Prism B) i 16–23 and p. 83 no. 4 (Prism D) i 14–19a, p. 103 no. 5 (Prism I) i 1´–7´, p. 111 no. 6 (Prism C) i 11´–17´, p. 212 no. 10 (Prism T) i 14–20, pp. 281–282 no. 15 ii 3–9, and p. 301 no. 23 (IIT) lines 27–29; and, in this volume, no. 116 i 1´, no. 196 rev. 5´ (subscript; building account damaged) and no. 222 lines 4–6.

[77] The Gate of the Abundance of the Land (bāb ḫiṣib māti) was likely located in the southwest wall of the so-called "Ostanbau," the new multi-room complex that Sennacherib had added onto the existing structure of Ešarra. For further discussion of the location of this gate, and the other seven gates of the eastern annex building, see Grayson and Novotny, RINAP 3/2 pp. 20–21 (esp. nn. 53–55). See also Novotny, JCS 66 (2014) pp. 100–102 figs. 2–4. The columns were placed in this important gateway of the temple sometime between 663 and 648, specifically after the composition of text no. 15 (date completely broken away; Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 pp. 281–282 ii 3–9), which does not mention the columns, and text no. 5 (Prism I; dated to V-8-648*; Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 103 i 1´–7´), which records the placement of them in the Gate of the Abundance of the Land.

[78] In text no. 3 (Prism B) ii 26–34a (Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 61), for example, Ashurbanipal states: "[Si]lver, gold, precious stones, as much property of his palace as there was, garment(s) with multi-colored trim, linen garments, large horses, people — male and female — (ii 30) two tall obelisks cast with shiny zaḫalû-metal, whose weight was 2,500 talents (and which) stood at a temple gate, I ripped (them) from where they were erected and took (them) to Assyria. I carried off substantial booty, (which was) without number, from inside the city Thebes." It is sometimes believed that the zaḫalû-metal mentioned in this passage was used to decorate the cella and ante-cella of Eḫulḫul, the temple of the moon-god Sîn at Ḫarrān (see below) and to construct a cast-metal-brick dais for the god Marduk in Babylon (Onasch, ÄAT 27/1 pp. 80 [n. 386], 156–158, and 161; and Novotny, Orientalia NS 72 [2003] pp. 211–215). Therefore, it is not unlikely that some of that treasure went to the Aššur temple at Aššur.

[79] Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 pp. 355–356 no. 61 rev. 1´–15´a.

Jamie Novotny

Jamie Novotny, 'Aššur', RINAP 5: The Royal Inscriptions of Ashurbanipal, Aššur-etel-ilāni, and Sîn-šarra-iškun, The RINAP/RINAP 5 Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, 2022 [http://oracc.org/rinap/rinap5/RINAP52Introduction/BuildingActivitiesinAssyria/Assur/]