Arbela and Milqiʾa

From the very start of his reign, Ashurbanipal actively supported the cult of Ištar of Arbela, whose principal place of worship was Egašankalama ("House of the Lady of the Land") in the citadel of Arbela (modern Erbil), as well as in the nearby city of Milqiʾa (possibly modern ʿAin Kawa), where her akītu-house was located.[90]

Extant inscriptions never state that Ashurbanipal worked on the structure of Ištar's temple and, thus, there is no written record of him having had Egašankalama renovated or rebuilt; presumably such work would have taken place at some point during his long reign. Numerous texts, however, state that he sumptuously decorated it with metal objects.[91] Unfortunately, it is generally unclear what types of objects and architectural features were clad in or fashioned from silver, gold, and copper since descriptions of the work on this temple in Ashurbanipal's inscriptions are rather vague.[92] A handful of texts do provide specific details about a few of the objects displayed in Ištar of Arbela's temple.[93] It is certain that metal-clad divine emblems (šurīnu) were set up in a (principal) gateway, and that at least two inscribed gold(-plated) bows (qaštu) were dedicated to her.[94] The divine emblems were fashioned at the outset of his reign, whereas the bows were made much later, shortly after the defeat and beheading of the Elamite king Teumman and sometime after Tammarītu was deposed by Indabibi and fled to Nineveh to implore the Assyrian king to forgive him for supporting Šamaš-šuma-ukīn in his rebellion against Assyria.

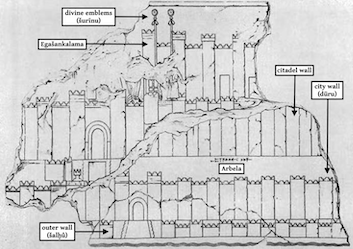

Figure 10. A depiction of Arbela from the North Palace, Room I, slab 9 (AO 19914). Drawing from V. Place, Ninive et l'Assyrie 3 pl. XLI no. 1.

Ashurbanipal, in an inscription written shortly after he became king, states:

The text seems to imply that in 668 Arbela did not have a proper city wall (dūru), but only an unfinished outer wall (šalḫû). Ashurbanipal claims to have built and completed both of them, as well as having them decorated. Given the lack of textual, as well as archaeological, evidence, it is impossible to confirm or refute this statement of Ashurbanipal.[96] If the claims are indeed true, then it is likely that work on the outer wall began during the reign of his father Esarhaddon or his grandfather Sennacherib and that the work on the larger, more impressive city wall had not yet been started, or was still in the very early stages of construction, that is, the mudbrick structure had not yet been raised to a significant height. At some point during Ashurbanipal's reign, Arbela's inner and outer walls appear to have been completed, if a relief depicting the city (AO 19914) accurately portrays this important cult center of Ištar at the time it was carved.[97]

Ashurbanipal, like his father before him, sponsored construction at Milqiʾa, the location of Ištar of Arbela's akītu-house, Egaledina ("Palace of the Steppe").[98] Despite Esarhaddon's claims of having completed the work on the New Year's temple, which he stated he had decorated with glazed bricks, and of celebrating a festival inside it during the month Ulūlu (VI), the month during which akītu-festivals were celebrated at Arbela, it appears that it was Ashurbanipal, not his father, who finished the work on Milqiʾa and Ištar's akītu-house there.[99]

Notes

[90] For Egašankalama, see George, House Most High p. 90 no. 351. S. Parpola (Parpola and Porter, Helsinki Atlas p. 13) has suggested that Milqiʾa might be identified as ʿAin Kawa, a proposal tentatively followed by A. Bagg (Rép. Géogr. 7/2–2 p. 429). N. Hannoon (Historical Geography pp. 315–316) has proposed that Tell Bastam, a site located ca. 27 km northeast of Arbela, should be identified as Milqiʾa, but as Bagg has already pointed out, that suggestion seems unlikely since the distance would be too far between Egašankalama and Ištar's akītu-house.

[91] Some of the work might have been started during the reign of his father and merely completed by him. For Esarhaddon's work on Egašankalama, see Leichty, RINAP 4 p. 117 Esarhaddon 54 rev. 16b–20a.

[92] Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 58 no. 3 (Prism B) i 19b–21, p. 83 no. 4 (Prism D) 16b–17, p. 114 no. 6 (Prism C) i 48´–49´, p. 139 no. 7 (Prism Kh) i 18´–20´, p. 216 no. 10 (Prism T) ii 7–8, p. 291 no. 21 line 5´, and p. 302 no. 23 (IIT) line 40b; and, in this volume, no. 185 (L3) lines 4–5, and no. 215 (Edition L) i 30´–32´.

[93] Text nos. 200–206.

[94] Text nos. 185 (L3) line 5, 200 rev. 15–22, and 203 rev. 9–14. The building reports of text nos. 201–202, and 204–206 are either completely missing or too badly damaged to be able to ascertain what type of object/emblem/ornament Ashurbanipal had fashioned for display in Egašankalama. The divine emblems (šurīnu) mentioned in text no. 185 (L3) might be shown on a wall relief depicting an image of Arbela and Ištar's temple (AO 19914; Barnett, Sculptures from the North Palace pls. 25–26).

[95] Text no. 185 (L3) lines 1–3.

[96] For a discussion of the Neo-Assyrian fortifications at Arbela, see Sollee, Bergesgleich p. 97 §§3.5.2–3.

[97] Barnett, Sculptures from the North Palace pls. 25–26. The upper register of a relief now in the Louvre (AO 19914; Figure 10) depicts Arbela with fully-constructed inner and outer city walls (with at least two gates), the citadel wall (with at least one entrance), the temple Egašankalama, and another building, possibly a palace.

[98] Text no. 185 (L3) lines 6–8. For Esarhaddon's work on this New Year's temple, see Leichty, RINAP 4 p. 117 Esarhaddon 54 rev. 20b–39. It is not entirely certain whether Egaledina was the Sumerian ceremonial name of Ištar of Arbela's akītu-house (see George, House Most High p. 87 no. 313) or an epithet ("palace of the steppe") for Milqiʾa (Parpola in Novotny, SAACT 10 p. 99 no. 19). For some information about the New Year's festival at Arbela and Milqiʾa, see Pongratz-Leisten in Parpola and Whiting, Assyria 1995 pp. 249–250.

[99] It was not uncommon for Esarhaddon to boast of finishing work on a temple and celebrating its completion with a grand festival. For example, compare Leichty, RINAP 4 pp. 127–128 Esarhaddon 57 (Aššur A) vi 1–vii 16. See the comments above about Ashurbanipal's work at Aššur.

Jamie Novotny

Jamie Novotny, 'Arbela and Milqiʾa', RINAP 5: The Royal Inscriptions of Ashurbanipal, Aššur-etel-ilāni, and Sîn-šarra-iškun, The RINAP/RINAP 5 Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, 2022 [http://oracc.org/rinap/rinap5/RINAP52Introduction/BuildingActivitiesinAssyria/ArbelaandMilqia/]