- Home

- Explore RINAP Home Page

- Browse Online Corpus

- Access RINAP 3 Scores

- Access RINAP 3 Sources

- RINAP 3/1 Front Matter

- RINAP 3/1 Introduction

- RINAP 3/1 Text Introductions

- RINAP 3/1 Back Matter

- RINAP 3/2 Front Matter

- RINAP 3/2 Introduction

- RINAP 3/2 Text Introductions

- RINAP 3/2 Back Matter

- Oracc Lemmatization Colors

- Citing RINAP URLs

- Reusing RINAP material

- RINAP Downloads

Nineveh, Part 3

27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38

27 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003501/]

Four small, fragmentary 'triangular' prisms from Nineveh are inscribed with a short inscription of Sennacherib that consisted only of the king's titles and epithets and a statement about the god Aššur supporting Sennacherib as his earthly representative. It is not known if these curious prisms had some functional purpose (foundation deposit, site marker, etc.) or if they were scribal exercises written on practice prisms. The objects were not inscribed before 698 or 697 (Sennacherib's 7th or 8th regnal year; see the commentary).

Access the composite text [/rinap/rinap3/Q003501/] or the score [/rinap/scores/Q003501/score] of Sennacherib 27

Sources [/rinap/scores/Q003501/sources]:

Commentary

These relatively small (ca. 4×16 cm) objects have been referred to as hexagonal prisms with three inscribed faces in previous literature. Actually, they are 'triangular' prisms with wide and fairly flat column dividers (ca. 1.3–2 cm). Thus, the three inscribed faces are referred to in this edition as cols. i, ii, and iii, and not as cols. i, iii, and v (with blank cols. ii, iv, and vi). Each column had ca. 22–27 short lines of text, often with only one word per line. Since the tops of exs. 1, 2, and 4 and the base of ex. 3 are preserved, it is certain that none of the four exemplars come from the same object. Moreover, exs. 1–3 were likely written by different scribes; the script of ex. 2 is neater and smaller than that of ex. 1 and the wedges of ex. 3 are more deeply impressed than those of exs. 1–2.

The text comprises only the prologue of text nos. 15–18 and 22–23. This oddity, as well as some orthographic abnormalities (ii 6, 8, and 10), may suggest that the objects were scribal exercises written on practice prisms. However, it cannot be ruled out that these three-sided prisms had some practical application, such as a foundation deposit or a site marker.

A precise date of composition cannot be determined with certainty. However, since the text (at least in ex. 4) includes a passage stating that the god Aššur made all of the black-headed people bow down at Sennacherib's feet, these prisms could not have been inscribed before 698 or 697, when that section was added to the prologue of the king's res gestae. Unfortunately, the evidence needed to determine if these objects were prepared ca. 694–689 (šulmu šamši or šalām šamši) is missing; in 694, 693, 692, or 691, ultu tiāmti elēnīti ša šulmu šamši ("from the Upper Sea of the Setting Sun") was changed to ultu tiāmti elēnīti ša šalām šamši.

NIN/89/10 (ex. 4) is included here courtesy of D. Stronach. A detailed study and edition of that fragment will appear in Pickworth, Nineveh 2, which is a catalogue of the small finds discovered during UC Berkeley's excavations at Nineveh.

The text, when complete, would have duplicated text no. 15 i 1–[26], text no. 16 i 1–26, text no. 17 i 1–21, text no. 22 i 1–19, and text no. 23 i 1–17. Because exs. 1–4 are all badly damaged, the master line is a conflation of all four exemplars. When possible, the line and column divisions follow ex. 1. A score of the inscription is presented on the CD-ROM.

Bibliography

28 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003502/]

A small fragment from the top of a clay prism, presumably from Nineveh, preserves two lines of a foundation inscription of Sennacherib. The extant text contains part of the report of the fourth campaign (against the people of Bīt-Yakīn living in Elam) that is narrated in numerous other inscriptions written on clay prisms.

Access Sennacherib 28 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003502/]

Source:

Commentary

Because the fragment preserves only the top of the prism and the middle part of two lines and because the piece could belong to any of the known editions of Sennacherib's res gestae inscribed on clay prisms, the text written on K 18318 is arbitrarily edited on its own. E. Frahm (Sanherib p. 109) has suggested that the line/column division most closely resembles that of text no. 15, which is written on octagonal prisms.

The text duplicates, for example, text no. 15 v 1–3, text no. 17 iv 9–10, and text no. 22 iii 68–69.

Bibliography

29 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003503/]

A small clay fragment, possibly from a prism and presumably from Nineveh, preserves a portion of the report of Sennacherib's third campaign (to the Levant) that is narrated in numerous other inscriptions written on clay prisms.

Access Sennacherib 29 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003503/]

Source:

Commentary

As E. Frahm (Sanherib p. 109) has already pointed out, Sm 2029 is too small to determine if it comes from a clay prism or a clay tablet. Because we are not certain about the type of object from which this fragment originates, this text is edited on its own. Should the piece come from a prism, then Sm 2029 may come from a hexagonal prism, as suggested by the width of the lines; Frahm (Sanherib p. 109) suggests that it may have come from a relatively late edition (691 or later). Should Sm 2029 come from a tablet, then it is possible that the fragment is part of the same object as Sm 2017 (Frahm, Sanherib pp. 238–239).

The extant text duplicates, for example, text no. 16 iii 28–40, text no. 17 ii 89–iii 5, and text no. 22 ii 62–73. Restorations are based on text no. 22.

Bibliography

30 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003504/]

A small fragment from the top of a clay prism, presumably from Nineveh, preserves two lines of a foundation inscription of Sennacherib. The extant text appears to contain part of the report of the third campaign (to the Levant) that is narrated in numerous other inscriptions written on clay prisms.

Access Sennacherib 30 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003504/]

Source:

Commentary

Because the fragment preserves only the top of the prism and the middle part of two lines and because the piece could belong to any of the known editions of Sennacherib's res gestae inscribed on clay prisms, the text written on Rm 25 is arbitrarily edited on its own. As far as we can tell, the text duplicates, for example, text no. 16 iii 1–2, text no. 17 ii 61, and text no. 22 ii 39–40.

Bibliography

31 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003505/]

A fragment of a decagonal clay prism, presumably from Nineveh, is inscribed with a late foundation inscription of Sennacherib. Only parts of the prologue and the report of the second campaign (a military expedition against the Kassites and Yasubigallians, and the land Ellipi) are preserved. Although the date lines are completely missing, the prism from which this small piece originates must have been composed relatively late in Sennacherib's reign (post-689).

Access Sennacherib 31 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003505/]

Source:

Commentary

J. Reade (JCS 27 [1975] p. 192) has suggested that 82-5-22,22 is a fragment of an octagonal prism and a duplicate of text no. 17. E. Frahm (Sanherib p. 109), however, thought that it belonged to a ten-sided prism because the angle of the two preserved faces best fits a decagonal prism. 82-5-22,22 was re-examined and checked against BM 103000 (text no. 17 ex. 1) and we agree with Frahm: this piece was probably from a ten-sided prism, despite the fact that there are otherwise no known decagonal prisms from the reign of Sennacherib (except text no. 32, which could possibly come from the same prism as this text). Although we cannot be certain, Sennacherib's scribes may have inscribed texts intended for Nineveh's walls on decagonal prisms sometime after 689, thus replacing octagonal prisms (text nos. 15–18) as the principal medium for those texts.

Frahm (Sanherib p. 109), on the basis of the script, suggests that 82-5-22,22 and Rm 2,98 (text no. 32) may have come from the same prism. This may be true, but it is best to edit both fragments individually.

The extant text duplicates, for example, text no. 22 i 4–11 and 73-79. Restorations are based on that inscription.

Bibliography

32 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003506/]

A fragment of a decagonal clay prism, presumably from Nineveh, is inscribed with a late foundation inscription of Sennacherib. Only parts of the reports of the second campaign (against the Kassites and Yasubigallians, and the land Ellipi) and the third campaign (to the Levant) are preserved. Although the date lines are completely missing, the prism from which this small piece originates must have been composed relatively late in Sennacherib's reign (post-689).

Access Sennacherib 32 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003506/]

Source:

Commentary

J. Reade (JCS 27 [1975] p. 192) has suggested that Rm 2,98 is a fragment of an octagonal prism and a duplicate of text no. 15 or text no. 16. E. Frahm (Sanherib p. 109), however, thought that it belonged to a ten-sided prism because the angle of the two preserved faces best fits a decagonal prism. Rm 2,98 was re-examined and checked against BM 103000 (text no. 17 ex. 1) and we agree with Frahm: this piece was probably from a ten-sided prism. Frahm (Sanherib p. 109), on the basis of the script, suggests that Rm 2,98 and 82-5-22,22 (text no. 31) may have come from the same prism. This may be true, but it is best to edit both fragments individually. The extant text duplicates, for example, text no. 22 ii 28–35 and iii 2–10. Restorations are based on that inscription.

Bibliography

33 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003507/]

In 1974, Manhal Jabur of the Mosul Museum discovered some fragments of clay prisms inscribed with texts of Sennacherib, along with inscribed bricks, in the northern courtyard of a building complex on the east side of Nineveh, south of the Khosr River and roughly equidistant from Kuyunjik and Nebi Yunus. The fragments, probably now in the Mosul Museum, have never been published and thus their contents are not known.

Access Sennacherib 33 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003507/]

Source:

Bibliography

34 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003508/]

A large stone tablet found at Nebi Yunus (Nineveh) is inscribed with a text summarizing the many accomplishments of Sennacherib on the battlefield and describing in detail the rebuilding and decoration of the armory (ekal kutalli, the "Rear Palace"). In total, ten of Sennacherib's military expeditions are included in this inscription: his first to eighth campaigns and the campaigns that took place in the eponymies of Šulmu-Bēl (696) and Aššur-bēlu-uṣur (695). With regard to work on the armory, Sennacherib describes its decoration in great detail. He records that he: (1) built a new palace consisting of two wings, one in the Syrian style and one in the Assyrian style, and a large outer courtyard; (2) had bull colossi made from pendû-stone, a rare and highly coveted reddish-brown stone quarried at Mount Nipur, and white limestone from the city Balāṭāya; (3) erected tall cedar columns on sphinxes made of pendû-stone; (4) cast large and elaborate objects out of bronze and copper, including human-headed colossi; and (5) constructed an elaborate pillared podium in the outer courtyard. Although the tablet is not dated, its terminus post quem is Sennacherib's eighth campaign, as the military narration ends with an account of the battle of Ḫalulê. Thus, the object was probably inscribed ca. 690–689. This text is sometimes referred to as the "Constantinople Inscription," "Memorial Tablet," or "Nebi Yunus Inscription."

Access Sennacherib 34 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003508/]

Source:

Commentary

The stone tablet was discovered, with other antiquities, at Nebi Yunus in 1852 (or 1854?) and became the possession of the governor of Mosul; for accounts of the tablet's discovery, see Rassam, Asshur pp. 4–7 and Budge, By Nile and Tigris 2 pp. 28–29. Fortunately, H. Rassam was allowed to make a copy of the inscription, which he sent to Sir H. Rawlinson; that copy was subsequently published in 1 R (pls. 43–44). Although it was stated in 1 R (pl. 43) that the tablet "is now in the Imperial Museum at Constantinople," this does not seem to have been the case, since repeated searches in various museums in Istanbul have not uncovered the tablet. E.A.W. Budge (By Nile and Tigris 2 p. 29) also states that he never succeeded in finding the tablet. Thanks are due to V. Donbaz for undertaking yet another search recently. Thus, if it ever did go to Istanbul, and there is no certainty that it did, the tablet is presumably in private hands or simply lost. Thus, the inscription could not be collated and its dimensions remain unknown.

Previous literature (for example, 1 R pls. 43–44 and Budge, By Nile and Tigris 2 p. 28) states that the inscription was written in two columns, with fifty lines of text in col. i and fifty-four lines of text in col. ii. As noted already by E. Frahm (Sanherib p. 128), the tablet was probably inscribed with fifty lines of text on the front and fifty-four lines of text on the back. Compare text no. 35 and text no. 36, both of which are stone tablets that have a single column of text written on the front and back.

Three inscriptions similar to this one are known: (1) text no. 26, which is inscribed on a hexagonal clay prism; (2) text no. 35, which is written on two stone tablets; and (3) a text written on a double-column clay tablet, K 2655 + K 2800 + Sm 318 (+)? K 4507 (+)? 89-4-26,150 (Frahm, Sanherib pp. 202–206 T 173; to be edited in Part 2). Many of the differences between this inscription and those texts are noted in the on-page notes.

In the copy published in 1 R (pls. 43–44), some of the inscription is in light, rather than heavy, type. It is uncertain whether this means that the text is faintly visible or totally missing and therefore restored. In such instances, the relevant passages are placed between half brackets (in the transliteration). The inscription is given consecutive line numbers for the obverse and reverse (= lines 51–94), rather than separate line counts for the obverse and reverse.

Bibliography

35 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003509/]

Two stone tablet fragments, both presumably from Nineveh, are inscribed with a text summarizing the accomplishments of Sennacherib on the battlefield and describing a building project of his at Nineveh, possibly the rebuilding and decoration of the armory (ekal kutalli, the "Rear Palace"). Parts of seventy-four lines are preserved and these contain reports of his sixth (against the Chaldeans living in Elam and against Nergal-ušēzib), seventh (against Elam), and eighth (the battle of Ḫalulê) campaigns, an account of a campaign to Arabia, and the beginning of the building report. The terminus post quem for the inscription is the expedition to Arabia, which took place after Sennacherib's eighth campaign, and therefore the tablets were probably inscribed ca. 690–689; they are probably later in date than text no. 34. The inscription is sometimes referred to as the "Ungnad Stone Tablet Fragment Inscription" or the "Winckler Stone Tablet Fragment Inscription." Ex. 1 is named after A. Ungnad, who published a copy of the fragment in 1907, and ex. 2 is named after H. Winckler, who published an edition of that piece in 1893–97.

Access the composite text [/rinap/rinap3/Q003509/] or the score [/rinap/scores/Q003509/score] of Sennacherib 35

Sources [/rinap/scores/Q003509/sources]:

Commentary

Three inscriptions similar to this one are known: (1) text no. 26, which is inscribed on a hexagonal clay prism; (2) text no. 34, which is written on a stone tablet; and (3) a text written on a double-column clay tablet, K 2655 + K 2800 + Sm 318 (+)? K 4507 (+)? 89-4-26,150 (Frahm, Sanherib pp. 202–206 T 173; to be edited in Part 2). Comparison with those texts suggests that this inscription probably contained a short prologue, military narration summarizing Sennacherib's first to eighth campaigns, the campaigns that took place in the eponymies of Šulmu-Bēl (696) and Aššur-bēlu-uṣur (695), and an expedition to Arabia, and a building report. The mention of Sennacherib reviewing enemy booty in line 14'' may indicate that the building account of this text described work on the armory; the reading of the extant text in that line is not entirely certain.

Since exs. 1 and 2 duplicate each other only in lines 10'–30', a score of those lines is provided on the CD-ROM. Although the master text of lines 10'–30' is a conflation of both exemplars, the line divisions follow ex. 1, which was not as wide as ex. 2. Parallel passages in text no. 34 aid in the restoration of damaged text in lines 1'–24' and 40'b–52', although caution must be exercised because there are major variants in those passages. Damaged text in lines 33'–40'a can be restored from text no. 22 v 31–41. For lines 25'–40'a, compare the Baltimore Inscription (Walters Art Gallery no. 41,109) lines 11b–12a, 14, and 41–43 (Grayson, AfO 20 [1963] pp. 88–91); Walters Art Gallery no. 41,109 and a duplicate of it housed at the Catholic University of America, two large stone tablets inscribed in 690 (the king's 15th regnal year), will be edited in Part 2, since that inscription (which has been referred to as the "Sur-marrati Inscription" and the "Fourteenth Year of Sennacherib Inscription") records work on the city wall of Sur-marrati and since the tablets upon which this text is written may originate from Samarra, and not Nineveh, where both exemplars of this text are presumed to have been discovered. The inscription is given consecutive line numbers for the obverse and reverse (= lines 32'–15''), rather than separate line counts for the obverse and reverse. Many of the differences between this inscription and text no. 34 are noted in the on-page notes.

VA 3310 (text no. 35 ex. 1), obverse of a stone tablet of Sennacherib, probably from Nineveh. Photo taken by O.M. Tessmer.

VA 3310 (text no. 35 ex. 1), reverse of a stone tablet of Sennacherib, probably from Nineveh. Photo taken by O.M. Tessmer.

Bibliography

36 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003510/]

A small, broken stone tablet discovered at Nineveh preserves the beginning and end of an inscription of Sennacherib recording his first campaign (against Marduk-apla-iddina II and his Chaldean and Elamite allies), his second campaign (against the Kassites and Yasubigallians, and the land Ellipi), and the renovation of three or more temples at Nineveh, some of which are said to have been last built by the ninth-century king Ashurnasirpal II (883–859). The text begins with an invocation of a number of gods (beginning with Aššur and ending with Ištar and the Sebetti). Although the tablet is not dated, its terminus post quem is Sennacherib's second campaign, as the military narration ends with an account of that military expedition. Thus, the object was probably inscribed ca. 702–701.

Access Sennacherib 36 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003510/]

Source:

Commentary

The tablet was discovered by R.C. Thompson during the 1929–30 excavation season at Nineveh, on the Kuyunjik mound between the Nabû and Ištar temples. J. Reade (CRRA 30 pp. 217–218) suggests that the object comes from the Ištar temple. The present location of the tablet is not known, but Thompson said that it was in Baghdad and therefore the object may be in the Iraq Museum (cf. Frame, ARRIM 2 [1984] p. 11). The object is said to be "small," but its dimensions have not been published.

Like text no. 34 and text no. 35, this tablet is inscribed on both the front and back. Only the left parts of the first seventeen and last twenty-one lines of the inscription are preserved. The text contains a prologue (invocation of gods and Sennacherib's titles and epithets), reports of the first two campaigns, the building account (work on some of Nineveh's temples), and advice to future rulers. Apart from text no. 10 (and probably also text nos. 11–13) and text no. 37, this is the only text in the extant Sennacherib corpus recording work on temples at Nineveh. This text records work on the Sîn-Šamaš temple, the temple of the Lady of Nineveh, and at least one other temple; the building account may have recorded the rebuilding of four, five, or even six different temples. Text no. 10 describes the construction of the shrine of the god Ḫaya and text no. 37 narrates the construction of the akītu-house Ešaḫulezenzagmukam ("House of Joy and Gladness for the Festival of the Beginning of the Year").

Restorations are based on the following texts: obv. 15–16 on the Baltimore Inscription line 2 (Grayson, AfO 20 [1963] p. 88); rev. 1'–2' on text no. 2 line 33 and text no. 3 line 33; rev. 8' on Grayson, RIMA 2 p. 309 A.0.101.40 line 35 and Leichty, RINAP 4 p. 126 Esarhaddon 57 v 9–12; rev. 9' on text no. 10 line 18; rev. 16'–18' on text no. 4 lines 91–92; and rev. 20'–21' on text no. 3 line 63. For other possible restorations, see Frahm, Studies Borger pp. 107–121.

Bibliography

37 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003511/]

A small, broken white limestone tablet found at the Nergal Gate of Nineveh in 1992–93 is inscribed with a text recording the construction of Ešaḫulezenzagmukam ("House of Joy and Gladness for the Festival of the Beginning of the Year"), a new akītu-house at Nineveh. Although only the first fifteen lines and the last eleven lines of the inscription are preserved, it is clear that Sennacherib did not deem the former New Year's temple, which was situated inside Nineveh (a fact recorded in an inscription of Sennacherib's grandson Ashurbanipal; see Borger, BIWA p. 169 Prism T v 33–34), suitable for use so he had a new one built outside the city wall, just north of the Nergal Gate; compare also K 1356 (Pongratz-Leisten, Ina Šulmi Īrub pp. 207–209), a text describing this king's rebuilding of an akītu-house outside the walls of the city Aššur. The extant text includes Sennacherib's titles and epithets, his commission as king by the god Aššur, the beginning and end of the building report, and a general description of the annual celebrations in the akītu-house. The tablet is dated to the eponymy of Nabû-kēnu-uṣur, governor of the city Samaria (690).

Access Sennacherib 37 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003511/]

Source:

Bibliography

38 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003512/]

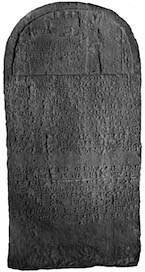

Three rounded-topped stone steles with images of the king and various divine symbols, found at Nineveh, are engraved with a text of Sennacherib recording the creation of a royal road by means of widening existing streets and by erecting steles as boundary markers on both sides of that road. The inscription concludes with a statement that if anyone in the future should build a house that encroaches upon the royal road, that person will be impaled on a stake over his/her house. This text is sometimes referred to as the "Inscription from the Royal Road."

Access Sennacherib 38 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003512/]

Sources [/rinap/sources/P450384,P450385,P450386]:

Commentary

Two of the steles, which would have originally been erected along the royal road that Sennacherib claims to have widened in this text, were discovered by H.J. Ross (1848) and E.A.W. Budge (1888–89) in the nineteenth century. In a popular account of his explorations of the ruins of Assyrian cities, A.H. Layard recounts the discovery of ex. 2: "At the foot of the mound Mr. Ross has found a monument of considerable interest. It was first uncovered by a man ploughing. ... It was erect, and supported by brickwork when discovered; and near it was a sarcophagus in baked clay. Mr. Ross suggests that the whole may have been an Assyrian tomb; but I question whether there is sufficient evidence to prove that its original site was where it was found; or that it had not been used, as portions of slabs with inscriptions at Nimroud, by the people who occupied the country after the destruction of the pure Assyrian monuments" (Nineveh 2 pp. 140–141); see also Ross, Letters from the East p. 144 (Letter No. 6, 24 January, 1848). E.A.W. Budge, in an account of his own travels in Ottoman lands, describes the discovery of ex. 1: "The day after my return from Baibûkh a native who farmed a little land between Ḳuyûnjiḳ and Nabi Yûnis came and told me that at a certain spot in one of his fields there was a large flat stone with figures and writing upon it, and he asked me to buy it from him. Taking a few men with digging tools and baskets Nimrûd and I went with him, and in a short time we uncovered a stele about 40 inches high and nearly 20 inches wide" (By Nile and Tigris 2 p. 77). Bezold, reportedly told by Budge, states that ex. 2 was discovered in a field just southeast of the Nebi Yunus mound.

Sennacherib states that he made steles so "there would be no diminution of the royal road" and that he erected the steles "on each side, opposite one another" (lines 19b–21). The credibility of Sennacherib's claim is supported by the facts that the king faces opposite directions in exs. 1 and 2 (to the right in ex. 1 and to the left in ex. 2), that the farmer who had discovered ex. 1 told Budge that "he had found several such stones and that they had all been broken up and burnt into lime" (Budge, By Nile and Tigris 2 p. 78), and that a third stele was discovered in July 1999 (ex. 3). Ex. 3 was reportedly discovered by a farmer to the southeast of Nebi Yunus; like ex. 2, the image of the king faces to the left.

There is a large blank space between lines 20 and 21 in all three exemplars, but the purpose of this is not known. See the comments in Unger, ABK p. 38.

E. Frahm (Sanherib p. 138) suggests that the steles were completed ca. 690 since text no. 18 vii 50'–51' records in its building report that Sennacherib widened a road of Nineveh to a width of fifty-two cubits, the same width as stated in this text. The steles may have been inscribed earlier (ca. 693–691) since we now know that text no. 18 ex. 1 (BM 127845+) was inscribed in the eponymy of Bēl-ēmuranni (691). Note also that the 693 and 692 editions of Sennacherib's res gestae that describe work in and around the city of Nineveh, texts written for the city's walls composed between text no. 17 and text no. 18, are not presently known; those inscriptions may have shed some light on when Sennacherib was working on the royal road.

The text of exs. 1–3 is virtually identical and therefore no score is given on the CD-ROM. The master text is generally ex. 1.

BM 124800 (text no. 38 ex. 2), one of the steles of Sennacherib that were erected along the fifty-cubit-wide royal road that ran through Nineveh.

Bibliography

A. Kirk Grayson & Jamie Novotny

A. Kirk Grayson & Jamie Novotny, 'Nineveh, Part 3', RINAP 3: Sennacherib, The RINAP 3 sub-project of the RINAP Project, 2025 [http://oracc.org/rinap/rinap3/RINAP31TextIntroductions/Nineveh/Part3/]