- Home

- Explore RINAP Home Page

- Browse Online Corpus

- Access RINAP 3 Scores

- Access RINAP 3 Sources

- RINAP 3/1 Front Matter

- RINAP 3/1 Introduction

- RINAP 3/1 Text Introductions

- RINAP 3/1 Back Matter

- RINAP 3/2 Front Matter

- RINAP 3/2 Introduction

- RINAP 3/2 Text Introductions

- RINAP 3/2 Back Matter

- Oracc Lemmatization Colors

- Citing RINAP URLs

- Reusing RINAP material

- RINAP Downloads

Nineveh, Part 2

14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26

14 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003488/]

Beginning in 698, Sennacherib's scribes abandoned clay cylinders in favor of (octagonal and hexagonal) clay prisms as the principal medium upon which this king's res gestae was written. J. Reade and A. Millard both report seeing a Sennacherib prism dated to the eponymy of Šulmu-šarri, governor of the city Ḫalzi-atbar (698); neither, however, provides additional information about the object or the text. Because the inscription seen by Reade and Millard is still unpublished (except for its date) and since the object (or a photograph of it) cannot be located, its contents are not known with certainty. Its content, we assume, was probably similiar (or identical) to that of text no. 15 (see the commentary for further details).

Access Sennacherib 14 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003488/]

Source:

Commentary

In 1975, J. Reade (JCS 27 p. 191), citing C. Walker as his source, reported that a prism dated to 698 was "in private hands." In 1992, A. Millard (SAAS 2 p. 122) noted that the object was in the Klassiska Institutionen of Göteborgs Universitet. Its present location is not known, but this Sennacherib prism may be in a private collection in Sweden. For additional information, see Frahm, Sanherib p. 65.

According to Millard (SAAS 2 p. 122), the prism was inscribed on the fourteenth day of the month Araḫsamna (VIII), in the eponymy of Šulmu-šarri, governor of the city Ḫalzi-atbar (mšùl-mu-LUGAL / LÚ.GAR.KUR URU.ḫal-zi-NA₄.at-bar).

E. Frahm proposes that this unpublished prism was octagonal since Sennacherib's scribes did not begin writing inscriptions on hexagonal prisms until 695. However, this may not be the case. At present, all of the known octagonal prisms (text nos. 15–18) were intended for Nineveh's inner and outer walls (Badnigalbilukurašušu and Badnigerimḫuluḫa), while all of the known hexagonal prisms whose building reports are preserved (text nos. 22–23 and 25) were written for the armory. The available source material does not exclude the possibility that Sennacherib's scribes wrote out texts on six-sided prisms as early as 698; such objects may have replaced cylinders as the principal medium of texts deposited in the structure of the "Palace Without a Rival" (and possibly the citadel wall) after 699. Therefore, it is not impossible that this unpublished prism was hexagonal.

With regard to the text itself, we can only speculate on its contents, just as Frahm has already done (Sanherib pp. 65–66). Given the fact that foundation inscriptions written in 699 and 697 contained a prologue, reports of the first four campaigns, a short passage stating that the king formed a large military contingent of archers and shield bearers, a building report, and concluding formulae, this text must have also had those same sections. As for the military narration, the accounts of Sennacherib's third and fourth campaigns either duplicate those of text no. 15 or deviate from those reports in a few places, just like text nos. 16 and 19–21; note that text nos. 19–21, all of which are written on hexagonal prisms, duplicate a text that is inscribed on a fragmentarily preserved bull colossus (Smith Bull 4; 3 R pls. 12–13).

With regard to the building report, its contents depend on whether the prism was six- or eight-sided. Frahm, assuming this prism is octagonal, proposes that the building report could duplicate that of text no. 15 or follow the style of those of text nos. 7 or 8. Cf. text no. 7 lines 1'–8', text no. 8 lines 1'–20' (with the on-page note to line 1'), and text no. 15 v 18–viii 18''; also compare text no. 16 v 41–viii 63, since it is better preserved than text no. 15. Should Frahm's conjectures prove correct, then this inscription would have been written for Nineveh's inner and outer walls (Badnigalbilukurašušu and Badnigerimḫuluḫa) or for the citadel wall. However, if the prism was hexagonal, one would expect the building report to have been much shorter than that of text no. 15; this would probably have been the case if the inscription was intended for prisms deposited in the structure of the "Palace Without a Rival" (for which no foundation record written after 700 is known with certainty). Thus, this section may have included: (1) an introduction to Sennacherib's building program at Nineveh; (2) a detailed account of the rebuilding of Egalzagdinutukua, the planting of a botanical garden, and the digging of canals for irrigating fields and orchards; (3) a general statement about enlarging Nineveh and restructuring its streets, alleys, and squares; and possibly (4) a passage recording the construction of a bridge. Reports of the construction of the inner wall (Badnigalbilukurašušu) and its fourteen gates, the building of the outer wall (Badnigerimḫuluḫa), the construction of aqueducts, and the creation of a marsh were probably omitted. In essence, the proposed building report follows the compositional arrangement of text no. 4, but with the expanded descriptions of text no. 15. Compare text no. 4 lines 61–92 to text no. 15 v 18–vii 13, 29'b–viii 1', and 8'b–18'; cf. also text no. 16 v 41–vii 21, 76b–80, 85–viii 3a, and 12–23. In sum, this inscription could either be a duplicate of text no. 15, a text very similar to that 697 edition of Sennacherib's res gestae (an intermediary edition between text nos. 8 and 15), or a unique text. Frahm tentatively proposes that this unpublished prism could be a copy of text no. 15 that was inscribed in the eponymy of Šulmu-šarri (698), one year earlier than the known dated exemplars, which were inscribed in the eponymy of Nabû-dūrī-uṣur, governor of the city Tamnunna (697).

Bibliography

15 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003489/]

Two fragmentarily preserved octagonal clay prisms and numerous prism fragments from Nineveh and Aššur are inscribed with a text describing Sennacherib's first four campaigns, the large-scale renovations of the "Palace Without a Rival" (the South-West Palace), the construction of Nineveh's inner and outer walls (Badnigalbilukurašušu and Badnigerimḫuluḫa), and many other public works at Nineveh. Sennacherib boasts also of forming a military contingent of 20,000 archers and 15,000 shield bearers from prisoners deported from conquered lands. The building report, which utilizes material from earlier inscriptions, includes: (1) an introduction to Sennacherib's building program at Nineveh; (2) a detailed account of the rebuilding of Egalzagdinutukua and the planting of a botanical garden; (3) a passage describing the construction of the great wall Badnigalbilukurašušu, with its fourteen gates, and the outer stone wall Badnigerimḫuluḫa; (4) a general statement about enlarging Nineveh, restructuring its public areas, and building its walls; (5) a brief report recording the building of aqueducts and a bridge; (6) reports of the creation of a game preserve and a marsh; and (7) an account of the digging of canals for irrigating fields and orchards given to the citizens of Nineveh. In connection with the construction of his palace, Sennacherib openly criticizes work sponsored by his predecessors. He states that they had depleted valuable resources, performed certain tasks (namely the transport of stone bull colossi) at the wrong time of year, and exhausted the workforce. Moreover, he notes that the work had been clumsily done and the result was not in good taste. The text concludes with a short passage stating that Sennacherib celebrated the completion of his palace; Aššur and other deities are said to have been invited inside, where they were presented with offerings and given gifts. Four exemplars preserve a date and these were all inscribed in the first half of the eponymy of Nabû-dūrī-uṣur, governor of the city Tamnunna (697). This text is sometimes referred to as "Cylinder C" in older publications.

Access the composite text [/rinap/rinap3/Q003489/] or the score [/rinap/scores/Q003489/score] of Sennacherib 15

Sources [/rinap/scores/Q003489/sources]:

| (1) BM 022508 [/rinap/sources/P393966/] (K 01674 + 1881-02-04, 0044 + 1883-01-18, 0598 + 1881-02-04, 0169 + 82-5-22,12) | (2) BM 121011 (+) BM 127985 + BM 128245 (+) A 16916 + A 16922 + A 16923 + A 16924 [/rinap/sources/P422299/] (1929-10-12,7 (+) 1929-10-12,641 + 1932-12-10,502) |

| (3) Bu 1889-04-26, 0177 [/rinap/sources/P450336/] | (4) BM 127970 (+) 1879-07-08, 0305 [/rinap/sources/P422745/] (1929-10-12, 0626 (+) 1879-07-08, 0305) |

| (5) Rm 0038 [/rinap/sources/P424606/] | (6) VA 08427 [/rinap/sources/P450337/] (Ass 20635) |

| (7) BM 127952 + 1879-07-08, 0002 [/rinap/sources/P422727/] (1929-10-12, 0608 + 1879-07-08, 0002) | (8) A 35257 [/rinap/sources/P392594/] (formerly PA 017) |

| (9) Bu 1889-04-26, 0145 [/rinap/sources/P450338/] | (10) BM 122612 [/rinap/sources/P422398/] (1930-05-08, 0001) |

| (11) K 01751 [/rinap/sources/P394029/] | (12) 1880-07-19, 0101 [/rinap/sources/P450339/] |

| (13) K 01838 [/rinap/sources/P394101/] | (14) VA 08436 [/rinap/sources/P450340/] (Ass 06643) |

| (15) 1883-01-18, 0766 [/rinap/sources/P450341/] | (16) 1879-07-08, 0003 [/rinap/sources/P450342/] |

| (17) VA 08421a + VA 08421b + VA 08421c–g (+) VA 08421h [/rinap/sources/P450343/] (Ass 14561a + Ass 14561b + Ass 14561c–g (+) Ass 14561h) |

Commentary

This inscription is very similar to text no. 16, but with less military narration and some variation in the building account. The two major features distinguishing this inscription from the following text are: (1) the military narration ends with a report of Sennacherib's fourth campaign; and (2) a passage recording the depositing of inscriptions in the foundation of the citadel terrace and the raising of that terrace by 190 courses of brick is included in this text. There are a few other variants in the building report and these are noted in the on-page notes.

The building report contains material composed anew for this inscription or for text no. 14 (if that prism is inscribed with a unique text), and passages borrowed (with changes) from the building reports of earlier inscriptions, namely text no. 1, text no. 4, and text no. 8. Additional information is provided in the on-page notes.

In some instances, the identification of certain fragments as exemplars of this text, rather than of some other inscription, is difficult and is based on very limited criteria. Ex. 3, although its preserved text does not deviate from text no. 16, is included here since it is dated to 697, and not 696 or 695, when certain exemplars of text no. 16 were inscribed. Ex. 5 is included here arbitrarily since R. Borger has suggested that it could belong to the same prism as ex. 1. Since a non-physical join between Rm 28 (ex. 5) and K 1674+ (ex. 1) is not entirely certain, Rm 28 is edited here as its own exemplar; note that the extant contents of that prism fragment duplicate both this text and text no. 16. The attribution of exs. 6 and 7 to this text is based solely on the fact that the preserved text on those pieces follows ex. 4 by omitting text no. 16 viii 50–51: iṣ-ṣu na-áš ši-pa-a-ti ib-qu-mu im-ḫa-ṣu ṣu-ba-ti-iš "they picked cotton (lit. "trees bearing wool") (and) wove it into clothing." The attribution of exs. 8 and 9 to this inscription is very uncertain as the text preserved on these fragments does not contain anything specific to this text or text no. 16. The suggestion that ex. 9 is a duplicate of ex. 1 goes back to J. Reade (JCS 27 [1975] p. 191), presumably based on the column divisions; col. ii' (= col. iv) begins with iii 27', which may indicate that the prism from which this fragment came contained accounts of only four campaigns. Both exemplars are arbitrarily included here. The attribution of exs. 10, 11, and 12 is based on the fact that there is insufficient room for the report of the fifth campaign. The attribution of ex. 13 is based on the fact that its contents follow ex. 1 by not omitting Frahm, Sanherib p. 75 Baub. lines 85–94 (= vi 32–41), a passage stating that Sennacherib deposited foundation inscriptions in the citadel terrace and raised that terrace by 190 courses of brick; cf. text no. 16 vi 52–53. The attribution of exs. 14 and 16 is based solely on the fact that they follow ex. 1 and omit text no. 16 vii 20: a-di iṣ-ṣu na-áš ši-pa-a-ti "together with cotton (lit. "trees bearing wool")."

Ex. 17 (VA 8421a–h) comprises eight fragments from the lower half of an eight-sided clay prism. Although parts of all eight columns and the bottom of the prism are preserved, most of the surface is very badly eroded. Because portions of the preserved text are completely illegible, only the legible lines are included in the catalogue.

There are twenty-nine other prism fragments that may be duplicates of this inscription, but they are not sufficiently preserved to determine whether they are actually exemplars of this text, rather than of some other inscription written on an octagonal prism. These fragments are edited with text no. 16 because that inscription is better preserved. The relevant pieces are exs. 1*–25*, 28*–29*, and 31*–32*. Moreover, K 4492 (Frahm, Sanherib p. 213 T 177), a fragmentarily preserved clay tablet from Nineveh (Kuyunjik), preserves part of the building report of this inscription. That fragment is not included here since it is from a tablet, not a prism, and is thus edited on its own in Part 2, with other texts inscribed on clay tablets.

BM 127970 and 79-7-8,305 almost certainly come from the same prism: they have a distinctive shape, the script is the same, and the contents do not overlap; and thus the fragments are edited as a single exemplar (ex. 4). K 1751 (ex. 11) and 80-7-19,101 (ex. 12) may belong to the same prism since K 1751 cols. i' and ii' end respectively with iv 35' and v 69 and 80-7-19,101 cols. i' and ii' begin respectively with iv 36' and vi 1. These two fragments, however, are not edited together as a single exemplar because it cannot be proven with certainty that K 1751 and 80-7-19,101 come from the same object. O. Pedersén (Katalog p. 155) suggests Ass 6643 (VA 8436; ex. 14) belongs to the same object as Ass 6673 (VA 8414) and Ass 6724 (Istanbul A 2039). This may be so, but it is best to edit them individually. Because it is unclear if Ass 6673 and Ass 6724 are fragments of a text recording work at Nineveh or at Aššur, those pieces are edited as text no. 16 exs. 29* and 32*. See the commentary of text no. 16 for further information.

The line numbering follows ex. 1 when possible, but the master line is a conflated text because of the fragmentary nature of ex. 1 (as well as of the other certain exemplars). The line count of this edition is based on the following exemplars: Ex. 1 in i 1–8, 1'–33', ii 1–10, 1''–22'', 28''–35'', iii 1–11, 16–19, 1'–33', iv 1–25, 1'–35', v 4–66, vi 12–68, vii 1–14, and viii 9''–28''; ex. 2 in i 34'–36', ii 23''–27'', 36''–37'', iv 36'– v 3, 67–vi 11, and 70–79; ex. 3 in vii 16'–29'; ex. 4 in vii 7'–15', 30'–31', and viii 1''–8''; ex. 5 in i 9–22 and viii 17'–19'; ex. 10 in iii 12–15; ex. 13 in vii 18–31; ex. 15 in vii 1'–5'; ex. 16 in vii 15–17 and viii 1'–15'; and ex. 17 in ii 1'–11'. A score of the inscription is presented on the CD-ROM. Restorations are based on text no. 16, text no. 17, and text no. 22; preference is given to text no. 16.

Bibliography

16 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003490/]

Two fragmentarily preserved octagonal clay prisms and numerous prism fragments from Nineveh, Aššur, and Kalḫu are inscribed with a text describing Sennacherib's first five campaigns, the formation of a large military contingent of archers and shield bearers, the large-scale renovations of the "Palace Without a Rival" (the South-West Palace), the construction of Badnigalbilukurašušu and Badnigerimḫuluḫa (Nineveh's inner and outer walls), and many other public works at Nineveh. Apart from the account of the fifth campaign (to Mount Nipur and against Maniye, king of the city Ukku) and some variation in the building report, this inscription is a near duplicate of text no. 15. With regard to the fifth campaign, Sennacherib had his scribes describe in his res gestae the extremely rugged mountain terrain that he and his army had to traverse; he records that in the most difficult places he had to clamber forward on his own two feet, sit down when his legs got tired, and drink cold water to quench his thirst. The Judi Dagh Inscription (to be edited in RINAP 3/2) is proof that Sennacherib campaigned in the region and, furthermore, that he had an inscription carved on rock faces to commemorate his hard-earned victory over the insubmissive inhabitants of the Mount Nipur region (Judi Dagh, in southern Turkey); this inscribing of the rock face at Judi Dagh, however, is not recorded in accounts of the king's fifth campaign. Upon his return to Nineveh, Sennacherib had his sculptors carve on his palace walls a relief depicting the narrow mountain passes through which his army marched and the difficult, steep terrain around the city Ukku. Two exemplars of this inscription preserve a date: one was inscribed in the eponymy of Šulmu-Bēl, governor of the city Talmusu (696), and the other in that of Aššur-bēlu-uṣur, governor of the city Šaḫuppa (695). This text is sometimes referred to as "Cylinder D" in older publications.

Access the composite text [/rinap/rinap3/Q003490/] or the score [/rinap/scores/Q003490/score] of Sennacherib 16

Sources [/rinap/scores/Q003490/sources]:

| (1) BM 127837 + BM 127969 + BM 128001 + BM 128010 + BM 128090 + BM 128219 + BM 128223 + BM 128225 + BM 128280 + BM 128290 + BM 128295 + BM 128314 + BM 128316 + BM 128318 + BM 128411 + BM 138188 [/rinap/sources/P422612/] (1929-10-12, 0493 + 1929-10-12, 0625 + 1929-10-12, 0657 + 1929-10-12, 0666 + 1929-10-12, 0746 + 1932-12-10, 0476 + 1932-12-10, 0480 + 1932-12-10, 0482 + 1932-12-10, 0537 + 1932-12-10, 0547 + 1932-12-10, 0552 + 1932-12-10, 0571 + 1932-12-10, 0573 + 1932-12-10, 0575 + 1932-12-10, 0668 + 1932-12-12, 0915) | (2) BM 103214 + BM 103216 + BM 103217 + BM 103219 + BM 103220 + 1913-04-16, 0160a [/rinap/sources/P422274/] (1910-10-08, 0142 + 1910-10-08, 0144 + 1910-10-08, 0145 + 1910-10-08, 0147 + 1910-10-08, 0148 + 1913-04-16, 0160a) |

| (3) K 01666 [/rinap/sources/P450344/] (R 105) | (4) Rm 037 [/rinap/sources/P424605/] |

| (5) K 01675 [/rinap/sources/P393967/] | (6) MV - [/rinap/sources/P450346/] |

| (7) Bu 1889-04-26, 0041 [/rinap/sources/P450347/] | (8) Rm 2, 091 [/rinap/sources/P424933/] |

| (9) BM 134510 [/rinap/sources/P423292/] (1932-12-12, 0505) | (10) BM 127929 [/rinap/sources/P422704/] (1929-10-12, 0585) |

Uncertain attribution

| (1*) BM 121022 + BM 127953 [/rinap/sources/P422310/] (1929-10-12, 0018 + 1929-10-12, 0609) | (2*) BM 121019 (+) A 16929 [/rinap/sources/P422307/] (1929-10-12, 0015) |

| (3*) Sm 2083 [/rinap/sources/P426259/] | (4*) Rm 1003 [/rinap/sources/P424908/] |

| (5*) A 16921 [/rinap/sources/P450345/] | (6*) BM 123427 [/rinap/sources/P422508/] (1932-12-10, 0370) |

| (7*) BM 134452 [/rinap/sources/P423183/] (1932-12-12, 0447) | (8*) Private Possession (New York, Mrs. L.H. Seelye) [/rinap/sources/P450348/] |

| (9*) BM 128271 [/rinap/sources/P423019/] (1932-12-10, 0528) | (10*) LB 3239 [/rinap/sources/P390298/] |

| (11*) 1881-07-27, 0009 [/rinap/sources/P450349/] | (12*) Rm 2, 056 [/rinap/sources/P450350/] |

| (13*) BM 122620 (+) A 08153 + A 16919 [/rinap/sources/P422406/] (1930-05-08, 0009) | (14*) ND 05414 [/rinap/sources/P450351/] |

| (15*) K 01651 [/rinap/sources/P393946/] | (16*) BM 121028 [/rinap/sources/P422316/] (1929-10-12, 0024) |

| (17*) BM 127950 [/rinap/sources/P422725/] (1929-10-12, 0606) | (18*) BM 134461 [/rinap/sources/P423192/] (1932-12-12, 0456) |

| (19*) BM 127919 [/rinap/sources/P422694/] (1929-10-12, 0575) | (20*) BM 134603 [/rinap/sources/P423285/] (1932-12-12, 0598) |

| (21*) Rm 0039 [/rinap/sources/P424607/] | (22*) Bu 1889-04-26, 0142 [/rinap/sources/P450352/] |

| (23*) VAT 09621 [/rinap/sources/P450353/] (Ass 19923) | (24*) BM 128327 [/rinap/sources/P423075/] (1932-12-10, 0584) |

| (25*) BM 099080 [/rinap/sources/P422120/] (Ki 1904-10-09, 0109) | (26*) A 16920 [/rinap/sources/P450354/] |

| (27*) ND 05416 [/rinap/sources/P450355/] | (28*) VA 08437 [/rinap/sources/P450356/] (Ass 06694) |

| (29*) VA 08414 [/rinap/sources/P450357/] (Ass 06673) | (20*) VA 08442 [/rinap/sources/P450358/] (Ass 015211) |

| (21*) VA Ass 04720 [/rinap/sources/P450359/] (Ass 22079a) | (22*) Ist A 02039 [/rinap/sources/P450360/] (Ass 06724) |

Commentary

This inscription is very similar to text no. 15, but with more military narration and some variation in the building account. The two major features distinguishing this inscription from the previous text are: (1) the military narration ends with a report of Sennacherib's fifth campaign; and (2) the passage recording the depositing of inscriptions in the foundation of the citadel terrace and the raising of that terrace by 190 courses of brick is omitted. There are a few other variants in the building report and these are noted in the on-page notes.

The evidence for considering exs. 3 and 10 as certain exemplars of this inscription is very limited. Although ex. 3 does not preserve text beyond the fifth campaign, it is fairly certain that K 1666 is an exemplar of this text, and not of text no. 17, as the line and column arrangement follow ex. 2 very closely; for this opinion, see also Reade, JCS 27 (1975) p. 192 and Frahm, Sanherib p. 69 (ex. c). The attribution of ex. 10 is based solely on the fact that it follows exs. 1 and 2 by having i-na 1 ME 90 ti-ip-ki ul-la-a re-ši-šu ("I raised its superstructure 190 courses of brick") in vi 38; cf. text no. 15 vi 19, which has am-šu-uḫ me-ši-iḫ-ta "I measured (its) dimensions." This is not, however, substantial proof that BM 127929 (ex. 10) preserves a copy of this inscription, rather than that of the previous text, especially since ex. 8 follows text no. 15 in this same passage. Following E. Frahm, ex. 10 is arbitrarily included here as if it were a certain exemplar.

Numerous other prism fragments could be duplicates of this text, but due to their poor state of preservation their attribution cannot be determined with certainty. Fragments that could be duplicates of text no. 15 or this text are edited as exs. 1*–23*, 28*–29*, and 31*–32*. Pieces that could be exemplars of text no. 15, this inscription, or text no. 17 are edited as exs. 24*–25*. Fragments that could be inscribed with copies of this inscription or text no. 17 are edited as exs. 26*–27*. In the case of exs. 1*–25*, they are edited here, rather than with text no. 15, since this inscription is generally the better preserved of the two texts. Moreover, exs. 28*–32* are all fragments of octagonal clay prisms from Aššur. Because the building report is not preserved on these pieces, it is not possible to determine with certainty if VA 8437, VA 8414, VA 8442, VA Ass 4720, and A 2039 (Istanbul) are exemplars of one of the known Nineveh inscriptions or an edition whose building report describes building activities at Aššur (VA 5061 + VA 5632a + VA 5632b + VA 7512 +? A 61 [unpublished] or VA 5634 [Frahm, KAL 3 no. 40]). Since the Aššur editions are badly damaged, these five fragments are tentatively edited here. Exs. 28*–29* and 31*–32* could be duplicates of text no. 15, this inscription, VA 5061+, or VA 5634. Ex. 30* could be a duplicate of this text, VA 5061+, or VA 5634. O. Pedersén (Katalog p. 155) suggests Ass 6643 (VA 8436; text no. 15 ex. 14) belongs to the same object as Ass 6673 (VA 8414; ex. 29*) and Ass 6724 (Istanbul A 2039; ex. 32*). This may be so, but it is best to edit them individually as the joins are not certain. VA 5061+ and VA 5634 will be edited in Part 2, with the inscriptions from Aššur. Ex. 32* is not included in the score as the piece was not examined; although a small portion of one column is visible in Ass ph 875, we are unable to positively identify the contents of ex. 32* col. i'.

Should exs. 1*–23*, 28*–29*, and 31* be exemplars of text no. 15, then those fragments would preserve the following lines of that inscription: ex. 1* is inscribed with i 1–21, ii 2–[...], iii 2–19, and viii 10'–19'; ex. 2* has i 1–20, ii 2–4', and iii 12–17; ex. 3* preserves i 1–21 and ii [...]–7'; ex. 4* has i 1–9 and ii 5–10 written on it; ex. 5* is inscribed with i 2–[...] and viii 4'–[...]; ex. 6* has i 4–17 and i 32'–38'; ex. 7* preserves i 6–[...], vii 2–7, and viii 2'–[20']; ex. 8* has viii 15'–2'' written on it; ex. 9* is inscribed with i [...]–21' and ii 3''–18''; ex. 10* has i 17'–39' and vi 48–59; ex. 11* preserves i 21'–ii 6 and ii 18''–37''; ex. 12* has ii 7–[...], iii 12–[...], and iv 23–[...] written on it; ex. 13* is inscribed with ii 8–[...], iii 10–[20], and iv 6–[26]; ex. 14* has ii 4'–[...] and iii 16–[...]; ex. 15* preserves ii [...]–10'' and iii 8'–16'; ex. 16* has ii 5''–11'' and iii 10'–19' written on it; ex. 17* is inscribed with iv 24–3'; ex. 18* has iv [...]–4'; ex. 19* preserves vi 3–11 and 72–vii 4; ex. 20* has vi 73–78 written on it; ex. 21* is inscribed with vi 75–vii 8 and viii 1'–15'; ex. 22* has vii 26–2'; ex. 23* preserves viii 1'–7'; ex. 28* has i 12'–17' written on it; ex. 29* is inscribed with i 24'–ii 10 and ii 26''–iii 10; and ex. 31* has iv 8'–27'.

With regard to ex. 6*, Frahm (Sanherib p. 70) tentatively suggests that this fragment is more likely a duplicate of text no. 15 based on the line divisions. Ex. 10* is known from F.M.Th. Böhl's transliteration in the "Böhl Archive" in Leiden, which he presumably copied in 1932 in the Iraq Museum and which he reports was purchased from a dealer in Mosul. Böhl's transliteration was unavailable for study and thus its entry in the score appears as ellipses (...) in the relevant passages. According to Frahm (Sanherib p. 71 ex. VV) col. "i" corresponds to text no. 22 i 40–52 (= i 55–72 of this text) and col. "vi" duplicates his Baub. lines 100–112 (= vi 60–71/72 of this text). J. Reade suggests that BM 134452 (ex. 7*) and BM 134461 (ex. 18*) could belong to the same prism; this is based on the script and the color of the clay. Frahm (Sanherib p. 70) suggests that BM 128271 (ex. 9*) and BM 127950 (ex. 17*) could belong to the same prism since they both have a similar black layer and other similar physical characteristics. This may be so, but it is best to edit them individually here.

Should exs. 24*–25* be exemplars of text no. 15 or text no. 17, then those fragments would preserve the following lines of those inscriptions: ex. 24* preserves text no. 15 i 11'–18'and viii 11''–16'' or text no. 17 i 40–47 and viii 69–74; and ex. 25* has text no. 15 ii 2–[...] and iii 7–16 or text no. 17 i 71–79 and ii 62–71 written on it.

Should exs. 26*–27* be exemplars of text no. 17, then those two fragments would preserve the following lines of that inscription: ex. 26* preserves text no. 17 ii 60–74, iii 48–63, and iv 38–47; and ex. 27* is inscribed with text no. 17 vii 54–69. Frahm (Sanherib p. 89) suggests that A 16920 (ex. 26*) and ND 5416 (ex. 27*) are probably exemplars of this inscription, rather than copies of text no. 17.

With regard to provenance, most of the exemplars come from Nineveh, but a few were discovered at Aššur (exs. 23* and 28*–32*) and Kalḫu (ex. 27*). The fragments comprising ex. 2 were purchased from the Parisian antiquities dealer I. Géjou; Frahm (Sanherib pp. 40 and 42) proposes that those pieces may have originated from Nineveh Area SH. Ex. 3 was acquired by C.J. Rich and purchased by the British Museum from Mrs. Rich in 1825; for details on the R[ich] collection (also 1825-5-3), see Stolper, Studies Larsen pp. 516–517 and Reade in Searight, Assyrian Stone Vessels p. 108. Ex. 6 was brought to Rome from Mosul by Maximilian Ryllo (1802–1848), a Jesuit Father, and presented to Pope Gregory XVI in 1838. For details on this gift from Ryllo's "expeditio Babylonica," see Peiser, OLZ 7 (1904) cols. 36–46 and Budge, By Nile and Tigris 2 pp. 26–27.

One might prefer to use BM 103214+ (ex. 2) as exemplar 1 and the master text because it is the earliest in date, but BM 127837+ (ex. 1) is used instead since it is better preserved. The line numbering follows ex. 1 when possible, but the master line is a conflated text because of the fragmentary nature of ex. 1 (as well as of the other certain exemplars). The line count of this edition is based on the following exemplars: Ex. 1 in i 17–57, 65–84, ii 30–56, 59–79, iii 15–22, 32–v 30, 41–vi 27, 56–vii 47, 60–85, and viii 4–73; ex. 2 in i 58–64, ii 1–2, 57–58, iii 1–6, v 31–40, vi 28–55, vii 48–59, and viii 1–3; ex. 1* in i 1–16, ii 3–14, and iii 7–13; ex. 2* in ii 15–18; ex. 3* in ii 19–20; ex. 13* in iii 23–28; ex. 14* in ii 21–29; and ex. 26* in iii 14. A score of the inscription is presented on the CD-ROM. Restorations are based on text no. 15, text no. 17, and text no. 22; preference is generally given to text no. 15.

Bibliography

17 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003491/]

Two nearly complete octagonal clay prisms and a few prism fragments from Nineveh are inscribed with a text describing seven military campaigns, the formation of a military contingent of 30,000 archers and 20,000 shield bearers from prisoners deported from conquered lands, the rebuilding and decoration of the "Palace Without a Rival" (the South-West Palace), the construction of Badnigalbilukurašušu and Badnigerimḫuluḫa (Nineveh's inner and outer walls) with their fifteen gates, and other public works at Nineveh, including the digging of several canals. The prologue, the reports of the first five campaigns, and numerous passages in the building report duplicate those same passages in earlier versions of Sennacherib's annals, especially text no. 16. The accounts of the events of the king's 9th and 10th regnal years included in this text are presently not known from other extant inscriptions, presumably because Sennacherib remained at home, in Nineveh. In the eponymy of Šulmu-Bēl (696), Sennacherib reports that Kirūa, the city ruler of Illubru, a man who had been a loyal Assyrian vassal, incited rebellion in Ḫilakku (Cilicia) and that the Assyrian army was sent to deal with the hostilities. The city Illubru was captured and plundered, and Kirūa and his supporters were defeated and brought back to Nineveh, where they were flayed alive. Afterwards, Illubru was reorganized as an Assyrian center. In the following year, in the eponymy of Aššur-bēlu-uṣur (695), Sennacherib records that he sent his army to the city Tīl-Garimme, where Gurdî, the king of the city Urdutu (a man who may have been responsible for Sargon II's death on the battlefield in 705), had incited rebellion. Urdutu is reported to have been taken and looted, but nothing is said about Gurdî, perhaps because he managed to escape. As for the building report, it is the longest and most detailed account of construction in and around Nineveh preserved in the Sennacherib corpus. It borrows material from earlier inscriptions and contains material composed anew for this text and other inscriptions written in 694 (Sennacherib's 11th regnal year). In connection with work on the "Palace Without a Rival," the king notes that the god Aššur and the goddess Ištar revealed to him the existence of cedar at Mount Sirāra, alabaster at Mount Ammanāna (the northern Anti-Lebanon), breccia at Kapridargilâ ("Dargilâ Village"), and limestone at the city Balāṭāya. He also takes credit for making significant advances in metalworking. In contrast to his predecessors, who are said to have ineffectually manufactured metal statues of themselves, Sennacherib boasts that he was able to efficiently and successfully cast tall columns and lion colossi from metal. In connection with supplying the huge number of gardens and orchards around Nineveh with water, Sennacherib reports that he had to look for new sources, as the waters of the Ḫusur River (mod. Khosr) were no longer sufficient. The king had three canals dug from the cities Dūr-Ištar, Šibaniba, and Sulu, all of which are located in the vicinity of Mount Muṣri (mod. Jebel Bašiqā). Two exemplars preserve a date and these were inscribed in the first half of the eponymy of Ilu-issīya, governor of the city Damascus (694). The inscription is commonly referred to as the "King Prism" or "Heidel Prism." Ex. 1 is named after L.W. King, who first published a copy and photographs of it in 1909, and ex. 2 is named after A. Heidel, who published an edition and photographs in 1953.

Access the composite text [/rinap/rinap3/Q003491/] or the score [/rinap/scores/Q003491/score] of Sennacherib 17

Sources [/rinap/scores/Q003491/sources]:

| (1) BM 103000 [/rinap/sources/P422273/] (1909-03-13, 0001) | (2) IM 056578 [/rinap/sources/P450362/] | (3) BM 102996 [/rinap/sources/P422272/] (1909-02-13, 0001) | (4) Rm 0026 [/rinap/sources/P424594/] |

Uncertain attribution

Commentary

The inscription written on the "King Prism" (ex. 1) and the "Heidel Prism" (ex. 2) is the longest preserved text of Sennacherib (ca. 740 lines). The following text (text no. 18), written a few years after this inscription (691), may have been one of the longest texts written during his reign (800+ lines), but it is very fragmentarily preserved. Text no. 17 includes a short prologue, accounts of Sennacherib's first five campaigns, reports of campaigns undertaken in the eponymies of Šulmu-Bēl (696) and Aššur-bēlu-uṣur (695), a passage stating that the king formed a large military contingent with prisoners from conquered lands, and a lengthy and detailed account of construction in and around Nineveh. The prologue and most of the military narration (reports of the first five campaigns) duplicate those same passages in text no. 15 and text no. 16. The accounts of the events of the king's 9th and 10th regnal years are known only from this inscription; these passages may have been composed anew for this edition. As for the building report, it also contains material composed anew for this inscription and passages borrowed (with changes) from the building reports of text no. 15 and text no. 16. Additional information is provided in the on-page notes.

Only the certain exemplars of this inscription are edited here. Ex. 1* (I2b 1502), however, is an exception. Although it duplicates (with some omission and variation) a passage of the building account presently known only from this inscription, the fragment is not sufficiently preserved to be certain it is an exemplar of this text. I2b 1502 is provisionally edited here, rather than on its own. The omissions and major variants are cited in the on-page notes. Since we were unable to study this fragment from the original, the transliteration of ex. 1* in the score is based on E. Frahm's transliteration (Sanherib p. 88), which is based on an unpublished copy of V.K. Šilejko sent to him by S. Hodjash.

Of the identified Sennacherib prism fragments in museum collections around the world there are four other fragments that could belong to this inscription rather than to one of the other texts written on octagonal prisms. These are edited with text no. 16 as exs. 24*–27*. See the catalogue and commentary of that inscription for further details.

The provenance of ex. 1 is uncertain. E.A.W. Budge (By Nile and Tigris 2 p. 23) states that BM 103000 "was found in a chamber built in the wall (or perhaps it was sunk in the actual wall), close to one of the human-headed bulls of one of the gates of Nineveh, and the bull near which it was placed must have been removed before it could be extracted from the wall. ... It is probable that cylinder No. 103,000 was discovered by the natives when they were breaking this bull into pieces, and we must be thankful that they had the sense enough to realize that it would fetch more money complete than when broken into pieces." J. Reade (JCS 27 [1975] p. 192), following Budge's account, tentatively suggests that ex. 1 came from the Nergal Gate. Frahm, drawing attention to a statement made by R.C. Thompson (Iraq 7 [1940] p. 85), points out that BM 103000 could have been discovered in Area SH (or similar provenance). According to records in the British Museum, this prism was purchased from I. Géjou. Thus, it is not impossible that ex. 1 was discovered as Budge describes and then purchased by Géjou, who in turn sold it to the British Museum.

A precise provenance for ex. 2 (IM 56578) is given by N. al Asil apud Heidel, Sumer 9 (1953) p. 117: "the prism was found embedded between the sun-dried bricks of the western wall of Nineveh, about three meters below the top of the wall, at a point about thirty meters north of where the present Mosul-Erbil road crosses the western city wall. He adds that there is no indication of a city gate at this point." Frahm (Sanherib pp. 87–88) suggests that Rm 26 (ex. 4) could have come from Area SH since Borger has proposed international joins between Rm 15, Rm 17, and Rm 18 and fragments in the Oriental Institute (Chicago). For the proposed provenance of the Chicago fragments purchased by E. Chiera, see for example Thompson, Iraq 7 (1940) p. 85.

While one might prefer to use IM 56578 (ex. 2) as exemplar 1 because it is the best preserved copy of the inscription, BM 103000 (ex. 1) has been used instead to conform with older editions, all of which follow the line numbering of that prism. The master text is based upon both exs. 1 and 2. A score of the inscription is presented on the CD-ROM.

Bibliography

18 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003492/]

A poorly preserved octagonal clay prism from Nineveh, and probably a small fragment of another prism, are inscribed with a text describing eight of Sennacherib's military campaigns and numerous building activities in and around Nineveh, including the rebuilding of the "Palace Without a Rival" (the South-West Palace), the construction of Nineveh's inner and outer walls (Badnigalbilukurašušu and Badnigerimḫuluḫa) with their eighteen gates, the creation of a fifty-two-cubit-wide royal road, and the digging and widening of a moat around the city. This inscription contains material from texts written earlier in the king's reign (especially from those written in 694–692) and material composed anew for this text and other inscriptions written in 691 (Sennacherib's 14th regnal year). Like the better preserved and known text nos. 22 and 23, the military narration of this edition of Sennacherib's res gestae includes accounts of eight campaigns: (1) against Marduk-apla-iddina II (biblical Merodach-baladan) and his Chaldean and Elamite allies in Babylonia; (2) against the Kassites and Yasubigallians, and the land Ellipi; (3) to the Levant, against an Egyptian-led coalition that had been organized by the nobles and citizens of the city Ekron, and against the Judean king Hezekiah; (4) against Bīt-Yakīn; (5) to Mount Nipur and against Maniye, king of the city Ukku; (6) against the Chaldeans living in Elam and against Nergal-ušēzib, the king of Babylon; (7) against Elam; and (8) the battle of Ḫalulê, where Assyrian forces fought Babylonian and Elamite forces led by Mušēzib-Marduk, the king of Babylon, and Umman-menanu (Ḫumban-menanu), the king of Elam. Accounts of the events of the king's 9th and 10th regnal years (696 and 695), those undertaken by his officials to Ḫilakku (Cilicia) and the city Tīl-Garimme, however, are not included among the king's victories on the battlefield. In connection with his work at Nineveh, Sennacherib records that he built the citadel wall (or some other structure in the citadel) as high as a mountain, created a wide road through the center of the city for triumphal processions, widened the moat that he had dug around the city earlier in his reign, and dug numerous canals in order to bring abundant water to Nineveh. One exemplar preserves date lines and that prism was inscribed in the eponymy of Bēl-ēmuranni, governor of the city Carchemish (691).

Access Sennacherib 18 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003492/]

Sources [/rinap/sources/P399282,P450363]:

Uncertain Attribution

Commentary

This inscription, which would have been one of the longest texts written under the auspices of Sennacherib (800+ lines), was composed in the eponymy of Bēl-ēmuranni (691; the king's 14th regnal year), three years after text no. 17; text no. 22 ex. 2 and text no. 23 ex. 1 were inscribed in the same year as ex. 1 (see below). The text, which was intended for octagonal clay prisms deposited in Nineveh's wall (just like text nos. 15–17), includes a short prologue, accounts of eight of Sennacherib's campaigns, and a lengthy and detailed account of construction in and around Nineveh. The prologue, most of the military narration (reports of the first seven campaigns), and much of the building report duplicate those same passages in text no. 17 and res gestae inscribed on (six- and eight-sided) prisms in 693 (the king's 12th regnal year) and 692 (his 13th regnal year); reports of the sixth campaign (against the Chaldeans living in Elam and against Nergal-ušēzib) were first recorded in texts written in the eponymy of Iddin-aḫḫē (693) and those of the seventh campaign (against Elam) were first described in res gestae written in the eponymy of Zazāya (692). Accounts of the eighth campaign (the battle of Ḫalulê), as well as sections of the building report, were composed anew for this text (and possibly other inscriptions written in 691). Because no intermediary editions of Sennacherib's res gestae between text no. 17 and this text are known, it is difficult to trace the editorial history of the various passages of the building report — that is, how the building report of text no. 17 evolved into that of this foundation inscription. Some additional information is provided in the on-page notes.

Ex. 1 presently comprises eight fragments, several of which are composed of many smaller fragments. For details on the (physical and non-physical) joins and the suggestion that the fragments belong to a single exemplar, see Frahm, Sanherib p. 90; cf. also Reade, JCS 27 (1975) pp. 193–194. In general, we agree with E. Frahm's assessment of the pieces. The various fragments of ex. 1 could very well belong to one and the same prism and thus we see no reason why all of the fragments of ex. 1 should not be edited together. Note, however, that BM 127914 may be part of another prism; the vertical ruling line between the columns does not appear to match that of the other fragments. As for the date of composition, collation reveals that the prism was inscribed in the eponymy of Bēl-ēmuranni (691). The date lines (viii 23'''–25''') now read: [...] x / [li-mu mEN-IGI-a]-⸢ni⸣ / [LÚ.EN.NAM URU.gar-ga]-⸢miš⸣ "[The month ..., (... day,) eponymy of Bēl-ēmurann]i, [governor of the city Carchem]ish." The traces of the NI and MES signs match exactly those in the date written on text no. 22 ex. 2. Cf. Frahm, Sanherib p. 94 and pl. III.

Ex. 1*, a fragment of an octagonal clay prism, is inscribed with either a copy of this inscription or another text whose military narration contained at least eight of Sennacherib's campaigns (up to the battle of Ḫalulê). Since the building report is not preserved, 83-1-18,605 is regarded here as a fragment of uncertain attribution.

E. Frahm (Sanherib p. 89) regarded 80-7-19,317 as a duplicate of this text, but it is more likely a duplicate of text no. 22 or text no. 23 since it appears to be from a hexagonal, not an octagonal, prism; that piece is edited as text no. 22 ex. 6*. A prism fragment published by V. Scheil (Prisme p. 45) could be a duplicate of this inscription, text no. 22, or text no. 23, but because we were unable to examine that piece, it is not known if it is part of a six- or eight-sided prism, and thus it is arbitrarily edited as text no. 22 ex. 9*.

Ex. 1 is the master text, but ex. 1* is the master text for col. iii 1''–9'' and col. iv 1''–11''. Since exs. 1 and 1* do not overlap, no score is provided on the CD-ROM. Restorations are based on text no. 17, text no. 22, and text no. 23; preference is generally given to text no. 22 (ex. 2) and text no. 23.

The tiny fragment K 19861 (Frahm, Sanherib p. 96) has traces of a line that duplicates vi 28' of this text (see the note to the line), but otherwise the scant traces do not seem to match this portion of the text.

Bibliography

19 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003493/]

A small fragment of a hexagonal clay prism, presumably from Nineveh, is inscribed with a text recording Sennacherib's first five campaigns, the creation of a large military contingent of archers and shield bearers, and presumably construction at Nineveh. The accounts of the third, fourth, and fifth campaigns, as far as they are preserved, duplicate those same reports of military narration in Smith Bull 4, an inscription written on a bull colossus stationed in Court H, Door a of Sennacherib's palace (the South-West Palace). This edition of the king's res gestae was probably written on prisms in 695, as suggested by the fact that the military narration ends with a report of the fifth campaign (to Mount Nipur and against Maniye, king of the city Ukku) and by the number of prisoners said to be conscripted into Sennacherib's army (20,400 archers and 20,200 shield bearers).

Access Sennacherib 19 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003493/]

Source:

Commentary

Unlike most of the other known inscriptions written on octagonal and hexagonal clay prisms (text nos. 15–18 and 22–23), the military narration of this text, as well as those of the next two inscriptions, follows that of Smith Bull 4 (3 R pls. 12–13). 83-1-18,599, a fragment preserving parts of two columns (cols. iii and iv, or possibly cols. iv and v), is the earliest known six-sided prism of Sennacherib, although this particular medium for foundation inscriptions with annalistic narration may have been in use since 698 (see the commentary of text no. 14). With regard to the year during which the prism from which this piece originates was inscribed, E. Frahm (Sanherib pp. 101–102) suggests 695 (rather than 696) not only because the military narration ends with an account of the fifth campaign (just like text no. 16), but because the number of prisoners conscripted into Sennacherib's army is greater than that of text no. 16; this inscription states that 20,400 archers and 20,200 shield bearers were added to the king's army, while text no. 16 records that Sennacherib formed a military contingent of only 20,000 archers (and) 15,000 shield bearers.

Following the style of text no. 22 and text no. 23, the building report of this inscription (which is completely missing) probably also described work on a single project at Nineveh; compare the building reports of texts inscribed on eight-sided prisms (text nos. 15–18), which record work on numerous projects in and around that same city. Therefore, the building report of 83-1-18,599 may have described the construction and decoration of the "Palace Without a Rival" (for which no foundation record written after 700 is known with certainty) or the armory (for which the earliest known accounts of its construction come from texts written in 691). Should it commemorate work on Egalzagdinutukua, as suggested by the fact that its military narration closely follows that of Smith Bull 4, then the description may have been similiar or identical to: (1) text no. 16 v 41–vii 21 and viii 3b–51; (2) text no. 17 v 23–vii 57 and viii 16–64; or (3) Smith Bull 4 lines 106b–161a.

The extant text duplicates Smith Bull 4 (3 R pls. 12–13) lines 30–33 and 43–47. Restorations are generally based on that inscription.

Bibliography

20 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003494/]

A small fragment of a (hexagonal?) clay prism, presumably from Nineveh, is inscribed with a foundation inscription with annalistic narration. Only part of the report of the sixth campaign is extant and that passage, as far as it is preserved, duplicates the contents of Smith Bull 4, an inscription written on a bull colossus stationed in Court H, Door a of Sennacherib's South-West Palace. The terminus post quem for this edition of Sennacherib's res gestae is the sixth campaign (against Elam) and thus the earliest date that the prism from which this fragment originates could have been inscribed is 693.

Access Sennacherib 20 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003494/]

Source:

Commentary

Sm 2093 is not sufficiently preserved to be able to determine with certainty whether it is from an octagonal or hexagonal prism. Because the extant text duplicates text known from Smith Bull 4 (3 R pls. 12–13) and since inscriptions duplicating reports of military narration on that same bull were written on six-sided prisms (text nos. 19 and 21), E. Frahm (Sanherib p. 102) has suggested that this small fragment may have been from a hexagonal prism. Following Frahm, Sm 2093 is tentatively regarded as part of a six-sided prism.

Given that only parts of sixteen lines are preserved, it is not possible to determine if the military narration of this edition of Sennacherib's res gestae ended with the report of the sixth campaign (just like Smith Bull 4) or with an account of the seventh (or even the eighth) campaign. Moreover, it is not known what project its building report commemorated; see the commentary of text no. 19 for some possibilities (assuming that Sm 2093 is from a hexagonal prism).

The extant text duplicates Smith Bull 4 (3 R pl. 12) lines 56–63. Restorations are based on that inscription.

Bibliography

21 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003495/]

A small fragment of a hexagonal clay prism, presumably from Nineveh, is inscribed with a foundation inscription with annalistic narration. Only parts of the accounts of the third and fourth campaigns are extant and those passages, as far as they are preserved, duplicate (with minor variation) the contents of Smith Bull 4, an inscription written on a bull colossus stationed in Court H, Door a of Sennacherib's palace (the South-West Palace). The piece is inscribed with either text no. 19, text no. 20, or another inscription. Because of similarities with the previous two inscriptions, it has been suggested that the prism from which this fragment originates was inscribed in 695 or 693; too little of the text is preserved to be certain of the date.

Access Sennacherib 21 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003495/]

Source:

Commentary

Like the previous two inscriptions, the military narration of this text follows that of Smith Bull 4 (3 R pls. 12–13), rather than that of texts inscribed on other octagonal and hexagonal clay prisms (text nos. 15–18 and 22–23). Since only a small portion of the original is preserved (the base and the lower parts of cols. ii and iii), it is no longer possible to determine if the prism is inscribed with a copy of text no. 19 (695; five campaigns and a building report), text no. 20 (probably 693; six or more campaigns and a building report), or another inscription. Therefore, it is edited on its own. Cf. J. Reade (JCS 27 [1975] p. 193), who tentatively suggests that Ki 1902-5-10,2 is inscribed with a 693 edition of Sennacherib's res gestae that described work on the armory. See also the commentaries of text nos. 19 and 20.

The extant text duplicates (with minor variation) Smith Bull 4 (3 R pl. 12) lines 23–24 and 34–36. Restorations are based on that inscription.

Bibliography

22 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003496/]

Two complete hexagonal clay prisms and several fragments of prisms from Nineveh are inscribed with a text describing eight of Sennacherib's military campaigns and the construction of a new armory. This inscription contains material from texts written earlier in the king's reign (especially those written in 694–692) and material composed anew for this text and other inscriptions written in 691 (Sennacherib's 14th regnal year). Like text no. 18 and text no. 23, the military narration of this edition of Sennacherib's res gestae includes accounts of eight campaigns: (1) against Marduk-apla-iddina II (biblical Merodach-baladan) and his Chaldean and Elamite allies in Babylonia; (2) against the Kassites and Yasubigallians, and the land Ellipi; (3) to the Levant, against an Egyptian-led coalition that had been organized by the nobles and citizens of the city Ekron, and against the Judean king Hezekiah; (4) against Bīt-Yakīn; (5) to Mount Nipur and against Maniye, the king of the city Ukku; (6) against the Chaldeans living in Elam and against Šūzubu (Nergal-ušēzib), the king of Babylon; (7) against Elam; and (8) the battle of Ḫalulê, where Assyrian forces battled Babylonian and Elamite forces led by Šūzubu (Mušēzib-Marduk), the king of Babylon, and Umman-menanu (Ḫumban-menanu), the king of Elam. Accounts of the events of the king's 9th and 10th regnal years (696 and 695), the campaigns undertaken by his officials to Ḫilakku (Cilicia) and the city Tīl-Garimme, however, are not included among the king's victories on the battlefield. In the building report, Sennacherib says that after he had completed the "Palace Without a Rival" (the South-West Palace) he started work on an armory, which he refers to as the ekal kutalli (the "Rear Palace"). He tore down the former palace, which he complains was too small, poorly constructed, and dilapidated. On a high terrace built upon a new plot of land (the Nineveh mound now called Nebi Yunus), Sennacherib constructed a new palace consisting of two wings, one in the Syrian style and one in the Assyrian style, and a large outer courtyard. He decorated the building in a fitting fashion, which included large limestone bull colossi stationed in its gateways. The two complete exemplars preserve a date. One (ex. 2) was inscribed in the eponymy of Bēl-ēmuranni, governor of the city Carchemish (691), and the other (ex. 1) was inscribed in the eponymy of Gaḫilu, governor of the city Ḫatarikka (689). The inscription is commonly referred to as the "Chicago Prism" or "Taylor Prism" (or "Taylor Cylinder" in earlier literature). Ex. 1 is named after the city in which it now resides (Chicago, in the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago); ex. 2 is named after Col. J. Taylor, who first acquired the object. The text has also been wrongly called by D.D. Luckenbill (and other scholars) the "Final Edition of the Annals."

Access the composite text [/rinap/rinap3/Q003496/] or the score [/rinap/scores/Q003496/score] of Sennacherib 22

Sources [/rinap/scores/Q003496/sources]:

| (1) A 02793 [/rinap/sources/P313081/] | (2) BM 091032 [/rinap/sources/P421809/] (1855-10-03, 0001) | (3) BM 103218 [/rinap/sources/P422275/] (1910-10-08, 0146) |

| (4) SM 0409 [/rinap/sources/P450368/] | (5) 1879-07-08, 0007 [/rinap/sources/P450370/] |

Uncertain attribution

| (1*) BM 033019 [/rinap/sources/P421798/] (1878-08-28, 0001) | (2*) 1879-07-08, 0307 [/rinap/sources/P450366/] | (3*) 1879-07-08, 0006 [/rinap/sources/P450367/] |

| (4*) BM 138185 [/rinap/sources/P450369/] (1932-12-12, 0912) | (5*) Sm 1026 [/rinap/sources/P370911/] | (6*) 1880-07-19, 0317 [/rinap/sources/P450371/] |

| (7*) 1880-07-19, 0004 [/rinap/sources/P450372/] | (8*) MFAB 1981.154 [/rinap/sources/P450373/] | (9*) Scheil, Prisme p. 45 [/rinap/sources/P450374/] |

| (10*) BM 099327 [/rinap/sources/P422254/] (Ki 1904-10-09, 0360) |

Commentary

This inscription, like text no. 18 ex. 1 and text no. 23 ex. 1, was composed in the eponymy of Bēl-ēmuranni (691; the king's 14th regnal year); we know from ex. 1 that this edition of Sennacherib's res gestae was inscribed on six-sided clay prisms at least until the month Duʾūzu (IV) in the eponymy of Gaḫilu (689; the king's 16th regnal year). Although the month and day that text no. 18 ex. 1 and text no. 23 ex. 1 were inscribed are missing, both of those prisms were probably inscribed earlier in the year than ex. 1 of this text, which is dated to the 20th day of the month Addaru (XII). Because the building account of text no. 23 is shorter than that of this inscription, it is possible that that text was written before this one and that the building report of this edition is an expanded version of that passage. Of course, it is not impossible that text no. 23 is the later of the two inscriptions; cf. the commentary of that text and Frahm, Sanherib p. 106.

The text was intended for hexagonal clay prisms deposited in the armory (just like text no. 23) and it includes a short prologue, accounts of eight of Sennacherib's campaigns, and a lengthy and detailed account of the building and decoration of the ekal kutalli (the "Rear Palace"). The prologue and most of the military narration (reports of the first seven campaigns) duplicate those same passages in text no. 17 and res gestae inscribed on (six- and eight-sided) prisms in 693 (the king's 12th regnal year) and 692 (his 13th regnal year); reports of the sixth campaign (against the Chaldeans living in Elam and against Nergal-ušēzib) were first recorded in texts written in the eponymy of Iddin-aḫḫē (693) and those of the seventh campaign (against Elam) were first described in res gestae written in the eponymy of Zazāya (692). Accounts of the eighth campaign (the battle of Ḫalulê) were composed anew for this text and other inscriptions written in 691; for literary allusions to Enūma eliš in the account of the battle of Ḫalulê, see Weissert, HSAO 6 pp. 191–202. The building report may be an expanded version of that of text no. 23, or possibly an earlier, longer version of it. Additional information on the differences between the two editions is provided in the on-page notes.

Exs. 3–5 are regarded as certain exemplars of this inscription because they all come from hexagonal clay prisms and since they all preserve part of the same building report as exs. 1–2. However, exs. 1*–10* are regarded as of uncertain attribution since they do not preserve the building account and therefore could be duplicates of text no. 23. E. Frahm (Sanherib p. 89) assigned 80-7-19,317 as a duplicate of text no. 18, but it is more likely a duplicate of this text or text no. 23 since it appears to be from a hexagonal, not an octagonal, prism; that piece is edited here as ex. 6*. A prism fragment published by V. Scheil (Prisme p. 45) could be a duplicate of text no. 18, this text, or text no. 23. Because we were unable to examine that piece, it is not known if it is part of a six- or eight-sided prism and thus it is arbitrarily edited here as ex. 9*. Moreover, its contents have not been included in the score; the variants noted by Scheil, however, are included in the minor variants. Should exs. 1*–10* be exemplars of text no. 23, then those fragments would preserve the following lines of that inscription: ex. 1* contains i 1–9 and 62–69; ex. 2* has i 1–4, v 9–19, and vi 8–16; ex. 3* preserves i 18–25 and ii 19–26; ex. 4* is inscribed with i 36–53 and ii 19–35; ex. 5* has i 75–ii 25 and ii 77–iii 27 written on it; ex. 6* contains iv 11–17 and v 11?–13?; ex. 7* has iv 24–35 and v 25–34; ex. 8* preserves v 3–11 and vi 13–16; ex. 9* is inscribed with v 9–24; and ex. 10* has v 27–37 and vi 22–26 written on it. Exs. 2* and 8* may be exemplars of this text rather than text no. 23 since they both include a reference to Nabû-šuma-iškun, a son of Marduk-apla-iddina II (Merodach-baladan), in the report of the eighth campaign, a detail omitted in text no. 23. However, one variant cannot be used to determine the attribution of these pieces with certainty.

J.H. Breasted recorded the purchase of the "Chicago Prism" (ex. 1) in a journal entry (April, 1920). He records: "I have come upon very important antiquities among the native dealers in Baghdad — especially a large six-sided baked clay prism, eighteen inches high, bearing the Royal Annals of Sennacherib. But many obstacles lie in the way of its purchase — the owner's exorbitant price, an export permit from the government, etc." (C. Breasted, Pioneer to the Past p. 275). R.C. Thompson (Iraq 7 [1940] p. 85) suggests that ex. 1 may have come from Area SH, rather than Nebi Yunus, since a considerable number of prisms and fragments were discovered just a few feet below the surface and thus many of the prisms and fragments sold on the market may have come from this area or a similar provenance. E. Frahm (Sanherib p. 103) has already correctly pointed out that Thompson's suggested provenance for ex. 1 is not based on concrete evidence.

With regard to the discovery of ex. 2, there is no firm evidence for when and where Col. J. Taylor acquired it; see Pallis, Antiquity of Iraq pp. 69–70. A.H. Layard (Nineveh 2 p. 186; and Discoveries p. 345) suggests the object was found at Nebi Yunus; he says nothing about when or how it came into the possession of Col. Taylor. L.W. King (CT 26 p. 8) states that Col. J.E. Taylor (error for Col. J. Taylor) discovered the hexagonal prism at Nebi Yunus in 1830 and that it was purchased by the British Museum some 25 years later; according to Budge, Sir H. Rawlinson purchased the six-sided clay object on behalf of the Trustees of the British Museum from Mrs. Taylor in July 1855. E.A.W. Budge (By Nile and Tigris 2 pp. 25–26) proposes that the object may have been purchased when Col. J. Taylor visited Nebi Yunus in 1830; he refutes F. Talbot's claim (JRAS 19 [1887] p. 135) that this prism was found at Kuyunjik. Budge also records that Rawlinson had a paper "rubbing" made of all six sides in 1840 and that R. Ready made a plaster facsimile for the British Museum from those "rubbings."

K. Radner (personal communication) has recently identified a prism fragment in the Sulaimaniya Museum (SM 409) as a duplicate of this inscription and that piece is included here as ex. 4 courtesy of her. She will publish photographs and an edition of SM 409 in AfO 52 (forthcoming).

While one might prefer to use the "Taylor Prism" (ex. 2) as exemplar 1 and the master text because it is the earliest in date, the "Chicago Prism" (ex. 1) has been used instead since its line numbering, as given in Luckenbill's edition, has become the standard. The variants that Luckenbill gives for ex. 2 are from the copy in 1 R pls. 37–42. Many of those "variants" are in fact mistakes in the copy and not on the original prism; for example, see the numeral in i 36 and the on-page note to vi 67. A score of the inscription is presented on the CD-ROM.

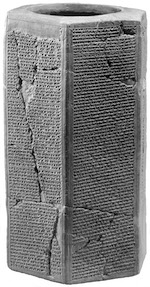

BM 91032 (text no. 22 ex. 2), the Taylor Prism of Sennacherib, which records eight military campaigns and the rebuilding of two wings of the armory.

Bibliography

23 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003497/]

A nearly complete hexagonal clay prism and a small fragment from another prism, both presumably from Nineveh, are inscribed with a near duplicate of text no. 22. This inscription contains the same prologue and military narration as the previous text, but its building report has a shorter description of the rebuilding of the armory, which Sennacherib refers to as the ekal kutalli (the "Rear Palace"). This report records the construction of only one wing of the building and its decoration, which included large limestone bull colossi stationed in its gateways; text no. 22 describes the building of two wings, one in the Syrian style and one in the Assyrian style, and a large outer courtyard. Both exemplars partially preserve dates. One prism (ex. 1) was written in an unknown month in the eponymy of Bēl-ēmuranni, governor of the city Carchemish (691), and the other (ex. 2) was inscribed in Intercalary Addaru (XII₂) of an unknown year. The inscription is commonly referred to as the "Jerusalem Prism"; ex. 1 is named after the city in which it now resides (Jerusalem, the Israel Museum).

Access the composite text [/rinap/rinap3/Q003497/] or the score [/rinap/scores/Q003497/score] of Sennacherib 23

Sources [/rinap/scores/Q003497/sources]:

Commentary

This inscription, like text no. 18 ex. 1 and text no. 22 ex. 2, was composed in the eponymy of Bēl-ēmuranni (691; the king's 14th regnal year). Because neither exemplar preserves a complete date, it is uncertain if this text was written prior to or after text no. 22. P. Ling-Israel (Studies Artzi p. 214 n. 11 and p. 220) suggests that ex. 1 of this text was written before text no. 22 ex. 2, which is dated to the 20th day of the month Addaru (XII), and proposes that that copy of text no. 23 was "not accepted as an official copy" and that text no. 22 ex. 2 was inscribed immediately after it. Ling-Israel elaborated further on the proposed relationship of the two inscriptions: "The major differences between the prisms are limited to the 'Building Inscription' (ekal kutalli section). Here, the scribe uses a less literary style than his fellow scribes who wrote the other two texts. The brevity of his version was not caused by lack of space. It was perhaps due to his different scribal education, and his different aims and conceptions. It is quite possible that the brevity and imperfection of his 'Building Inscription' was the major cause for the rejection of his eight-campaign version by the official royal scribal tradition. For two years later (in 689 B.C.E.), when a new copy of the text was commissioned, it was the version of another prism (namely, that of the Taylor Prism) which was selected as a model, and not his." S.J. Lieberman (JAOS 112 [1992] p. 689) very tentatively reads the month the prism was inscribed in as ⸢ITI.BÁR.ZAG.GAR⸣, "the month Nisannu (I)," which, if correct, would clearly place the date of ex. 1 of this text much earlier than text no. 22 ex. 2; cf. also his remarks on the quote above. We cannot, however, confirm Lieberman's reading from the published photographs of the object; see also Frahm, Sanherib p. 106. E. Frahm raises the possibility that ex. 1 (Israel Museum 71.72.249) may have been inscribed at the same time as ex. 2 (BM 134449a), which is dated to Intercalary Addaru (XII₂) of an unknown year, and therefore the prisms were inscribed one month later than text no. 22 ex. 2. Frahm rightly notes that there is no known evidence for Intercalary Addaru (XII₂) in the eponymy of Bēl-ēmuranni (691). There is no reason, however, to assume that ex. 1 and ex. 2 were written at the same time. Comparison of the building reports of this inscription and text no. 22 suggests to us that this inscription may have been the earlier of the two prism inscriptions, namely since this inscription describes the construction of only one wing of the armory, rather than two wings and an outer courtyard. Thus, the report of the armory's construction in text no. 22 may be a later, expanded version of the building report of ex. 1 of this text. Because we lack firm evidence, we cannot exclude the possibility that text no. 22 ex. 2 is earlier than ex. 1 of this text. Should this prove to be the case, then the building report of this text would be a later, abridged version of the building report of text no. 22.

The text, which was intended for hexagonal clay prisms deposited in the armory (just like text no. 22), includes a short prologue, accounts of eight of Sennacherib's campaigns, and an account of the building and decoration of a wing of the ekal kutalli (the "Rear Palace"). Additional information on the differences between this inscription and text no. 22 is provided in the on-page notes.

BM 134449a (ex. 2) duplicates only a small portion of ex. 1. Although it follows very closely the building report and concluding formulae of this text, the piece is not sufficiently preserved to be absolutely certain that it preserves a copy of this text, rather than another inscription written ca. 691–689. Following Frahm (Sanherib p. 105), BM 134449a is edited here as if it were a certain exemplar.

In addition to these two exemplars, there are ten other prism fragments that may preserve copies of this text. These are edited as exs. 1*–10* of text no. 22. See the catalogue and commentary of that text for further details.

The provenance of ex. 1 is presumed to be Nineveh. It was purchased by the Israel Museum from Sotheby's (8 December 1970; lot no. 148) at the recommendation of A. Shaffer; that purchase was made possible by the contributions of Mrs. M. Sacher (London) and Mrs. J. Ungeleider (New York). Ex. 2 was discovered at Nineveh by R.C. Thompson, but its find spot was not recorded.

Ex. 1 is the master text. Since ex. 2 preserves only a small portion of the text, a partial score (v 48–63 and vi 48–61) is provided on the CD-ROM. Restorations are based on text no. 22.

Israel Museum 71.72.249 (text no. 23 ex. 1), the Jerusalem Prism of Sennacherib, which records eight military campaigns and the rebuilding of one wing of the armory.

Bibliography

24 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003498/]

A fragment of a hexagonal clay prism, and possibly a second prism fragment, presumably from Nineveh, are inscribed with a foundation inscription written after Sennacherib captured Babylon and its king Šūzubu (Mušēzib-Marduk) in late 689. Only a small portion of the complete text is extant. The prologue, parts of reports of the first campaign (against Marduk-apla-iddina II and his Chaldean and Elamite allies), second campaign (against the Kassites and Yasubigallians, and the land Ellipi), and the second conquest of Babylon, and the beginning of the building account (or a report of an expedition to Arabia) are preserved. With regard to the capture of Babylon in 689, Sennacherib records that he returned the gods of the city Ekallātum to their rightful place after 418 years and that he utterly destroyed Babylon and its temples by diverting water from canals; the actual destruction was probably not as bad as Sennacherib describes. Although neither exemplar preserves a date, the prisms were inscribed in 688 (eponymy of Iddin-aḫḫē; the king's 17th regnal year) or later.

Access the composite text [/rinap/rinap3/Q003498/] or the score [/rinap/scores/Q003498/score] of Sennacherib 24

Sources [/rinap/scores/Q003498/sources]:

Uncertain Attribution

Commentary

J. Reade (JCS 27 [1975] p. 194) and E. Frahm (Sanherib p. 106) tentatively assign K 1665 (ex. 1*) as a duplicate of K 1634 (ex. 1), the only certain exemplar of this inscription; Frahm notes that line lengths and line divisions of the two pieces are similar. Ex. 1* does not preserve enough text to be certain that it is inscribed with the same text as ex. 1. Following Reade and Frahm, K 1665 is tentatively edited with K 1634. Since the pieces overlap, it is certain that these fragments do not come from the same prism. Frahm (Sanherib pp. 106–107) has raised the possibility that BM 134559 could be a duplicate of K 1634 (ex. 1); this tentative attribution is based solely on the fact that there appears to be sufficient room for a report of the destruction of Babylon in 689 between col. i' 12', which describes the battle of Ḫalulê, and col. ii' 1', which records the construction of the armory at Nineveh. Whether or not BM 134559 is a duplicate depends on the contents of K 1634 col. i' 17'–18' (= vi 17'–18'). These two lines contain the first two lines of either the building account or a report of military narration. Frahm (Sanherib p. 107) forwards the possibility that these badly damaged lines could preserve the beginning of a report describing an expedition to Arabia or the opening lines of an account recording work on the Sebetti temple at Nineveh, a project otherwise not attested in the extant Sennacherib corpus; for details, see the on-page note to vi 17'–18' and Frahm, Sanherib p. 107. Too little is preserved to confirm or reject these conjectures. Because we cannot identify the contents of K 1634 col. i' 17'–18' with certainty and because we cannot prove that BM 134559 is inscribed with the same inscription as K 1634, it is best to edit that fragment on its own (text no. 25).

The text, we assume, included a short prologue, accounts of eight of Sennacherib's campaigns and the conquest and destruction of Babylon in 689, and a report of building at Nineveh (the armory, the Sebetti temple, or another building); this inscription may also include a report describing an expedition to Arabia. In addition to the uncertainty about the contents of vi 17'–18' (building report or military narration), it is not known if the report of the battle of Ḫalulê (the eighth campaign) in this inscription duplicated that of the 691–689 editions of Sennacherib's res gestae (text nos. 18 and 22–23) or that of the Bavian Inscription, as E. Weissert (HSAO 6 p. 202) has suggested. Compare text no. 22 v 17–vi 35 to the Bavian Inscription lines 34b–43a (Luckenbill, Senn. pp. 82–83).

The master text is ex. 1 in i 23–26 and vi 1'–18', and ex. 1* in i 1–11 and ii 1'–9'. Col. i 12–22 is a conflation of both exemplars, but the line division follows ex. 1. Because exs. 1 and 1* overlap in only a few lines, a partial score (i 12–22) is provided on the CD-ROM. Col. i 1–26 and ii 1'–9' duplicate text no. 22 i 1–25 and ii 29–36. Col. vi 1'–16' duplicate the Bavian Inscription lines 48–54a (Luckenbill, Senn. pp. 83–84). Restorations are based on those inscriptions.

Bibliography

25 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003499/]

A fragment of a hexagonal clay prism from Nineveh is inscribed with a foundation inscription that was most likely written after Sennacherib captured Babylon and its king Šūzubu (Mušēzib-Marduk) in Kislīmu (IX) 689. Although only a small portion of the report of the eighth campaign (the battle of Ḫalulê) and the building report (the armory at Nineveh) are preserved, this edition of the king's res gestae, like text no. 24, probably contained an account of the second conquest of Babylon, during which that city and its temples are said to have been utterly destroyed. The building report, as far as it is preserved, contains the same description of work on the armory (ekal kutalli, the "Rear Palace") as text no. 22. Because only small portions of the complete text are preserved, it is not impossible that this fragment is inscribed with a copy of text no. 24, rather than with that of another inscription. Although its date lines are missing, the prism to which this fragment belongs was probably inscribed in 688 (eponymy of Iddin-aḫḫē; the king's 17th regnal year) or later.

Access Sennacherib 25 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003499/]

Source:

Commentary

E. Frahm (Sanherib pp. 106–107) has raised the possibility that BM 134559 could be a duplicate of K 1634 (text no. 24 ex. 1) because there appears to be sufficient room for a report of the destruction of Babylon in 689 between col. i' 12' and col. ii' 1'. Because we cannot identify the contents of K 1634 col. i' 17'–18' (= text no. 24 vi 17'–18') with certainty and because we cannot prove that BM 134559 is inscribed with the same inscription as K 1634, it is best to edit this fragment on its own. For details, see the commentary of text no. 24.

The text, we assume, included a short prologue, accounts of eight of Sennacherib's campaigns and the second conquest of Babylon, and a report of work on the armory. It is possible that it also included a report describing an expedition to Arabia.

The extant text, which would have been in cols. v and vi, duplicates text no. 22 vi 16–25 and 61–70. Restorations are based on that inscription.

Bibliography

26 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003500/]

A fragment from the lower part of a hexagonal clay prism from Nineveh is inscribed with a foundation inscription summarizing the many accomplishments of Sennacherib on the battlefield and describing one of his building activities at Nineveh. The text, as far as it is preserved, is similar to text no. 34, a text inscribed on a large stone tablet. The portion that remains, which comes from the bottom of cols. i and ii of the prism, contains abbreviated reports of his first five campaigns, the campaign that took place in the eponymy of Šulmu-Bēl (696; Sennacherib's 9th regnal year), and his seventh campaign. Presumably, the missing portions of the military narration included accounts of the campaign that took place in the eponymy of Aššur-bēlu-uṣur (695; the king's 10th regnal year), the eighth campaign, and possibly one or more of his post-691 campaigns (the conquest and destruction of Babylon in 689, to Arabia, etc.). As for the building report, it may have described the rebuilding and decoration of the armory, as suggested by the fact that this inscription closely parallels text no. 34. Although the date lines are completely broken away, this edition of Sennacherib's res gestae is generally thought to have been written in 687 (eponymy of Sennacherib; the king's 18th regnal year) or later.

Access Sennacherib 26 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003500/]

Source:

Commentary

Because only a small portion of the complete text is preserved and because the extant text duplicates inscriptions written on other media, it is difficult to accurately assess the contents of this edition of Sennacherib's res gestae; the same is true for the year during which the prism was inscribed. Thus, any statements about its contents, date, and length are largely speculative. E. Frahm (Sanherib p. 108), having compared the text preserved on BM 121025 with the one inscribed on a large stone tablet, the so-called "Nebi Yunus Inscription" (text no. 34), noted that: (1) the inscription probably included reports of the campaign that took place in the eponymy of Aššur-bēlu-uṣur (695; against the city Tīl-Garimme) and the eighth campaign (the battle of Ḫalulê); (2) the prism may have been much smaller than other known octagonal and hexagonal prisms of Sennacherib, with ca. 43 lines per column, for a total of ca. 258 lines of text (1:2.3 ratio); (3) the building report may have been the same or similar to that of the "Nebi Yunus Inscription" (text no. 34); and (4), assuming no. 3 above, there appears to be sufficient room (ca. 42 lines) for report(s) of Sennacherib's post-691 campaigns. Given the lack of evidence, we can add little to Frahm's conjectures.

The contents are similar to text no. 34 lines 10–17 and 34–39 and K 4507 i 1'–4' (Frahm, Sanherib pp. 202–203 T 173; to be edited in Part 2). Col. i 1', 4'–5', 7', 16'–17', ii 1'–3', 5'–7', and 10' deviate from text no. 34. When possible, restorations are based on text no. 34. Many of the differences between this inscription and text no. 34 are noted in the on-page notes.

Bibliography

A. Kirk Grayson & Jamie Novotny

A. Kirk Grayson & Jamie Novotny, 'Nineveh, Part 2', RINAP 3: Sennacherib, The RINAP 3 sub-project of the RINAP Project, 2025 [http://oracc.org/rinap/rinap3/RINAP31TextIntroductions/Nineveh/Part2/]