Formation of the Neo-Babylonian Empire and Later Military Campaigns

According to Berossos, Nabopolassar served as general in the Assyrian army.[[9]] However, this statement made in classical sources cannot be confirmed from contemporary and later cuneiform sources. Nevertheless, it is clear from chronographic texts that Nabopolassar proved to be an effective military leader and strategist. Regardless of his background, Nabopolassar was not only able to sever Babylonia's decades-long dependence on Assyria, but also to erase the once-great and powerful Assyrian Empire from the political landscape, thereby allowing him to establish a relatively-stable and powerful Babylonian state, one that lasted almost a hundred years.

In 627 and 626, Nabopolassar took advantage of the (chaotic) political situation that ensued after the deaths of Kandalānu (r. 647–627) — the Ashurbanipal-appointed king of Babylon — and Aššur-etel-ilāni (r. 630–627) — Ashurbanipal's young son and successor on the Assyrian throne who came to and held power with the help of the powerful eunuch Sîn-šumu-līšir — and seized power for himself. On twenty-sixth day of Araḫsamna (VIII) of 626, he ascended the throne in Babylon.[[10]] After he declared himself king, it took Nabopolassar six years to remove Assyrian troops from Babylonia. Until the end of 620, he intensely fought for control over Babylonia with the Assyrian king Sîn-šarra-iškun (r. 626–612), who was another son of Ashurbanipal (r. 668–ca. 631).[[11]] Sometime after 12-X-620,[[12]] Nabopolassar held complete control over Babylonia.

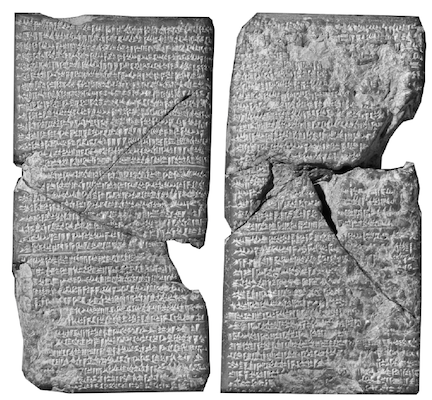

Figure 1. Obverse and reverse of the "Fall of Nineveh Chronicle" (BM 21901). © Trustees of the British Museum.

Until 615, Sîn-šarra-iškun, with the assistance of allied troops from Egypt, was able to keep Nabopolassar at bay, mostly because the battles fought between the two rulers took place in northern Babylonia or in the Middle Euphrates region, and not on Assyrian soil. Everything, however, changed in 615, when Cyaxares (Umakištar), "the king of the Umman-manda" (Medes), joined the fight. In that turn-of-events year, Nabopolassar invaded the Assyrian heartland and attacked Aššur. He failed to capture that important religious center and was forced to retreat south, as far as the city Takritain (mod. Tikrit). In the following year, 614, Cyaxares marched straight into the heart of Assyria and roamed effortlessly through it, first capturing Tarbiṣu, a city very close to Nineveh, and then Aššur, which the Babylonians had failed to take in 615.[[13]] Upon hearing this news, Nabopolassar quickly marched north and forged an alliance with the Median king. The unexpected union not only gave fresh impetus to Nabopolassar's years-long war with Sîn-šarra-iškun, but also removed any hopes that the Assyrian king might have had about the survival of his kingdom. Sîn-šarra-iškun could clearly see the writing on the wall and he took what measures he could to fortify Nineveh.[[14]] In 613 (if not earlier, in 614 or 615), that city's gates were reinforced by narrowing them with massive blocks of stone. The death blow for Sîn-šarra-iškun and his capital came during the following year, in 612. Nineveh's fortifications, even with the improvements made to its defenses, were not sufficient to prevent a joint Babylonian-Median assault from breaching the city's walls. After a three-month siege — from the month Simānu (III) to the month Abu (V) — Nineveh fell and was looted and destroyed.[[15]] Before the city succumbed to the enemy,[[16]] Sîn-šarra-iškun died. Unfortunately, the true nature of his death — whether he committed suicide, was murdered by one or more of his officials, or was executed by the troops of Nabopolassar or Cyaxares — is not recorded in cuneiform sources, not even in the Fall of Nineveh Chronicle (see below).[[17]]

Although Nineveh was in ruins and Sîn-šarra-iškun was dead, the Assyrian Empire still had a little bit of fight in it. Aššur-uballiṭ II (r. 611–609), a man who was very likely the son and designated heir of Sîn-šarra-iškun, declared himself king of Assyria in Ḫarrān, an important provincial capital located in the northwestern part of Assyria, near the Baliḫ River (close to modern Urfa).[[18]] Assyria's last ruler — who could not officially be crowned king of Assyria since the Aššur temple at Aššur was in ruins and thus the ancient coronation ceremony that would confirm him as Aššur's earthly representative could not be performed[[19]] — relied upon Assyria's last remaining ally: Egypt. While Nabopolassar's armies consolidated Babylonia's hold over the Assyrian heartland in 611, Aššur-uballiṭ was able to prepare for battle in his makeshift capital. In 610, Nabopolassar, together with Cyaxares, marched west, crossed the Euphrates River, and headed directly for Ḫarrān, Assyria's last bastion. As the Babylonian and Median forces approached the city, Aššur-uballiṭ and his supporters fled since any fight would have been futile. By saving his own skin, this Assyrian ruler put off the final death blow of his kingdom by one year. When the armies of Nabopolassar and Cyaxares arrived at Ḫarrān, they thoroughly looted and destroyed it and its principal temple Eḫulḫul, which was dedicated to the moon-god Sîn. During the following year, 609, Aššur-uballiṭ returned with a large Egyptian army and attacked the Babylonian garrisons that Nabopolassar had stationed near Ḫarrān. Despite this minor victory, he failed to retake the city. By the time, the king of Babylon arrived on the scene, Aššur-uballiṭ and his Egyptian allies were no longer in the vicinity of Ḫarrān and, therefore, he marched to the land Izalla and attacked it instead. Aššur-uballiṭ was never to be heard from again. The once-great Assyrian Empire was gone, but not forgotten.[[20]]

After the conquest of Assyria, during his final years as king (608–605),[[21]] Nabopolassar carried out campaigns in the area north of the former Assyrian heartland and especially in Syria-Palestine (the land Ḫatti), in the area where Egypt tried to regain its influence after the fall of the Assyrian Empire. Babylonian control over the region west of the Euphrates River was not accomplished during Nabopolassar's lifetime. That would only be achieved after his son and successor Nebuchadnezzar II became king.

9 de Breucker, Babyloniaca p. 252 Berossos F8d. This piece of information is preserved in the work of Eusebius; compare also Beaulieu, Special Issue of Oriental Studies p. 128.

10 Chronicle Concerning the Early Years of Nabopolassar lines 14–15a; see the Chronicles section below for a translation of that passage. For a recent overview of this same period, see Novotny, Jeffers, and Frame, RINAP 5/3 pp. 35–37 (with references to previous studies).

11 The two men vied for control over Babylon, Nippur, Sippar, and Uruk. It is clear that Uruk changed hands on more than one occasion; see Beaulieu, Bagh. Mitt. 28 (1997) pp. 367–394.

12 The latest economic document dated to Sîn-šarra-iškun's reign from Babylonia comes from Uruk and it is dated to 12-X-620 (Brinkman and Kennedy, JCS 35 [1983] p. 58 no. O.45).

13 On the last days of the city Aššur, see Miglus, ISIMU 3 (2000) pp. 85–99; and Miglus, Befund und Historierung pp. 9–11. There is evidence of burning throughout the city. The Assyrian kings' tombs, which were located in the Old Palace, were looted, their sarcophagi smashed, and their bones scattered and (probably) destroyed; see Ass ph 6785 (MacGinnis in Brereton, I am Ashurbanipal p. 284 fig. 292), which shows the smashed remains of an Assyrian royal tomb. It has been suggested that this destruction might have been the work of Elamite troops, who were paying Assyria back for Ashurbanipal's desecration of Elamite royal tombs in Susa in 646, which is described as follows: "I destroyed (and) demolished the tombs of their earlier and later kings, (men) who had not revered (the god) Aššur and the goddess Ištar, my lords, (and) who had disturbed the kings, my ancestors; I exposed (them) to the sun. I took their bones to Assyria. I prevented their ghosts from sleeping (and) deprived them of funerary libations" (Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 250 Asb. 11 [Prism A] vi 70–76).

Kalḫu was also destroyed in 614 and again in 612. See D. Oates and J. Oates, Nimrud passim; and Miglus, Befund und Historierung pp. 8–9. A well in Ashurnasirpal II's palace (Northwest Palace) filled with the remains of over one hundred people attests to the city's violent end (D. Oates and J. Oates, Nimrud pp. 100–104). Some of the remains might have been removed from (royal) tombs desecrated during Kalḫu's sack, while other bodies were thrown down there alive, as suggested from the fact that the excavators found skeletons with shackles still on their hands and feet in that location. While Nabû's temple Ezida was being looted and destroyed, the exemplars of Esarhaddon's Succession Treaty (Parpola and Watanabe, SAA 2 pp. XXIX–XXXI and 28–58 no. 6) that had been stored (and displayed) in that holy building were smashed to pieces on the floor. For evidence of the selective mutilation of bas reliefs in the Northwest Palace, see Porter, Studies Parpola pp. 201–220, esp. pp. 210–218. For an overview of the widespread destruction of Assyria's cities, see MacGinnis in Brereton, I am Ashurbanipal pp. 280–283.

14 As J. MacGinnis (in Brereton, I am Ashurbanipal p. 280) has pointed out, "the very size of the city [Nineveh] proved to be its fatal weakness. The length of its wall — a circuit of almost 12 kilometers — made it impossible to defend effectively at all places." The fact that Nineveh had eighteen gates, plus the Tigris River nearby and the Khosr River that passed through the city, did not help.

15 For evidence of Nineveh's destruction, which included the deliberate mutilation of individuals depicted on sculpted slabs adorning the walls of Sennacherib's South-West Palace and Ashurbanipal's North Palace, see, for example, Reade, AMI NF 9 (1976) p. 105; Reade, Assyrian Sculpture p. 51 fig. 73; Curtis and Reade, Art and Empire pp. 72–77 (with figs. 20–22), 86–87 (with figs. 28–29), and 122–123; Stronach in Parpola and Whiting, Assyria 1995 pp. 307–324 (with references to earlier studies) ; Reade, RLA 9/5–6 (2000) pp. 415–416 §14.3 and pp. 427–428 §18; Porter, Studies Parpola pp. 203–207; Reade, in Brereton, I am Ashurbanipal pp. 32–33 (with fig. 28); and MacGinnis in Brereton, I am Ashurbanipal p. 281. One of the more striking examples of the selected mutilation by Assyria's enemies is the wide gash across Sennacherib's face in the so-called "Lachish Reliefs" (BM 124911) in Room XXXVI of the South-West Palace (Reade, Assyrian Sculpture p. 51 fig. 73). There is evidence of heavy burning in the palaces. The intensity of Nineveh's last stand is evidenced by excavation of the Halzi Gate, where excavators discovered the remains of people (including a baby) who had been cut down by a barrage of arrows as they tried to flee Nineveh while parts of the city were on fire. See Stronach in Parpola and Whiting, Assyria 1995 p. 319 pls. IIIa–b.

16 Some (fictional) correspondence between Sîn-šarra-iškun and Nabopolassar from the final days of the Assyrian Empire exists in the form of the so-called "Declaring War" and "Letter of Sîn-šarra-iškun" texts. The former (BM 55467; Gerardi, AfO 33 [1986] pp. 30–38), which is known from a tablet dating to the Achaemenid or Seleucid Period, was allegedly written by Nabopolassar to an unnamed Assyrian king (certainly Sîn-šarra-iškun) accusing him of various atrocities and declaring war on the Assyrian, stating: "[On account] of the crimes against the land Akkad that you have committed, the god Marduk, the great lord, [and the great gods] shall call [you] to account [...] I shall destroy you [...]" (rev. 10–14). The (fictional) response is a fragmentary letter (MMA 86.11.370a + MMA 86.11.370c +MMA 86.11.383c–e; Lambert, CTMMA 2 pp. 203–210 no. 44), known from a Seleucid Period copy, purported to have been written by Sîn-šarra-iškun to Nabopolassar while the Assyrian capital Nineveh was under siege, pleading to the Babylonian king, whom the besieged Assyrian humbly refers to as "my lord," to be allowed to remain in power. For further details about these texts, see, for example, Lambert, CTMMA 2 pp. 203–210 no. 44; Frahm, NABU 2005/2 pp. 43–46 no. 43; Da Riva, JNES 76 (2017) pp. 80–81; and Frazer, Akkadian Royal Letters.

17 See Novotny, Jeffers, and Frame, RINAP 5/3 p. 27 n. 178.

18 On Aššur-uballiṭ II, see, for example, J. Oates, CAH2 3/2 p. 182; Brinkman, PNA 1/1 p. 228 sub Aššūr-uballiṭ no. 2; Radner, Tall Šēḫ Ḥamad pp. 17–19; Frahm, Companion to Assyria p. 192; Radner in Yamada, SAAS 28 pp. 135–142; and MacGinnis in Brereton, I am Ashurbanipal pp. 283–284.

19 On Aššur-uballiṭ remaining as the heir designate, rather than the king, of Assyria, see Radner in Yamada, SAAS 28 pp. 135–142.

20 For Assyria after 612, its "afterlife," and legacy (with references to previous literature), see, for example, Curtis, Continuity of Empire pp. 157–167; Frahm, Companion to Assyria pp. 193–196; and Hauser in Frahm, Companion to Assyria pp. 229–246. For Nabopolassar and Nebuchadnezzar II modelling the organization of their central palace bureaucracy and imperial administration on Assyria's, see Jursa, Achämenidenhof pp. 67–106; and Jursa, Imperien und Reiche pp. 121–148. Urban life continued to some extent in Assyria's once-grand metropolises and the cult of the god Aššur survived in Aššur. See, for example, Miglus, Studies Strommenger pp. 135–142; Dalley, AoF 20 (1993) pp. 134–147; Dalley, Hanging Garden pp. 179–202; Frahm, Companion to Assyria pp. 193–194; and Radner, Herrschaftslegitimation pp. 77–96. A handful of "post-Assyrian" legal contracts have been discovered at Dur-Katlimmu (mod. Tell Sheikh Hamad), a site on the eastern bank of the Khabur River. These texts come from the early reign of the Neo-Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II, between 603 and 600; see Postgate, SAAB 7 (1993) pp. 109–124; and Radner, Tall Šēḫ Ḥamad pp. 61–69 nos. 37–40.

21 These events are chronicled in the Chronicle Concerning the Late Years of Nabopolassar; see the Chronicle section below for a translation.

Jamie Novotny & Frauke Weiershäuser

Jamie Novotny & Frauke Weiershäuser, 'Formation of the Neo-Babylonian Empire and Later Military Campaigns ', RIBo, Babylon 7: The Inscriptions of the Neo-Babylonian Dynasty, The RIBo Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, 2024 [/ribo/babylon7/RINBE11Introduction/Nabopolassar/FormationoftheNeo-BabylonianEmpireandLaterMilitaryCampaigns/]