Inscriptions

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 1001 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023

01

This text was engraved on nine stone tablets from Aššur, most of which were discovered in the ruins of the Aššur temple. Just as in other inscriptions of this ruler, there is a strong Babylonian influence in the language and script of the text, as well as in the prominent role of the god Enlil; that deity is praised alongside Aššur in the inscription's prologue (lines 1–17) and replaces (or is identified with) the Assyrian national god in the building report (lines 18–58) as the main occupant of the temple Eamkurkurra.

Ist EȘEM 05223 (Ass 00887). Messerschmidt, KAH 1 no. 2

The main body of the inscription, the section between the introduction and concluding formulae, comprises three parts, with each being dedicated to a different ideological topos.

Although the building under construction is referred to as the "temple of the god Enlil," a strong ideological bond can be made between the temple, the king, and the city of Aššur through a sort of literary stratagem: the Akkadian "translation" that typically follows the Sumerian ceremonial name of the temple goes well beyond the punctual correspondence between words and adds a praise of the god Enlil ("my Lord") and the city of Aššur ("my city") before the concluding clause šumšu abbi ("I called it"; lines 52–58). The breakdown of the passage is as follows:

bīt rīm mātātim (Akkadian translation: "Temple – Wild Bull of the Lands")

bīt dEnlil bēliya (first insertion: dedication to Enlil instead of Aššur)

ina qereb āliya Aššurki (second insertion: Ashur-bond)

šumšu abbi

After the building report, the inscription presents an ideological picture of the period "when I built the temple" by giving a utopian description of prices (of barley, wool, and oil), which is reminiscent of southern Mesopotamian practices (e.g. Sîn-kāšid, Sîn-iddinam, Sîn-iqīšam).

Immediately before the concluding formulae -- which contains advice to future rulers and curses -- Samsī-Addu records that he received tribute from the city Turkiš and from a king of the Upper Land and states that he set up a monumental inscription in Lebanon, on the shore of the Mediterranean Sea. In this way the Assyrian king boasts about the extent of his dominion, which stretched from Turkiš (in northwestern Iran) in the east to the Sea of the Setting Sun in the west and, thus controlled everything, not just the land between Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, a region that Samsī-Addu claims to have pacified.

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005645/] of Samsī-Addu I 01.

Source

| (1) Ist EȘEM 05223 (Ass 00887) | (2) Ist EȘEM 09520 |

| (3) Private collection | (4) Ist EȘEM 06877 (Ass 00863 + Ass 00891 (+) Ass 00899 + Ass 00947) |

| (5) Ass 17541 | (6) Ass 06575 |

| (7) Ass 16423 | (8) Ass 16628 |

| (9)Ass 16986 |

Bibliography

02

This inscription is reconstructed from numerous fragmentarily preserved stone cylinders and two rectangular blocks. Despite their poor state of preservation, it is assumed that all of pieces included here (see the catalogue below) bore the same single inscription since they were all discovered in the vicinity of the Ištar temple at Nineveh and since their physical characteristics are similar; according to A.K. Grayson (RIMA 1 p. 52), the cylinders are made of an imported black stone and, according to J. Reade, the rectangular-shaped blocks (exs. 4 and 7) are made from the same type of stone (Reade 2000).

The text, which is written in archaizing script, records the rebuilding of Emenue and Ekituškuga, respectively the temple and ziggurat of the goddess Ištar at Nineveh; the former is located on the citadel mound, within the temple complex of Emašmaš, a place where Samsī-Addu claims to have unearthed foundation documents (narê u temmēnī) of the earlier Sargonic king Man-ištušu, a son of the famous Sargon of Agade [http://cdli.ox.ac.uk/wiki/doku.php?id=biography_sargon]. As part of the restoration work, Samsī-Addu states that he returned the inscriptions of Man-ištušu that his workmen had discovered, placing them beside his own inscribed objects (presumably those written bearing this text); although no inscribed objects of this Akkadian ruler have been found in the ruins of the Ištar temple at Nineveh, monuments of Man-ištušu have been recovered from the Sippar "museum" (cf. RIME 2 p. 74–6), including imported black stone cylindrical- and rectangular-shaped foundation deposits inscribed with that ruler's so-called "standard inscription."

An inscription of the Middle Assyrian ruler Aššur-uballiṭ I written in archaizing script is engraved on a rectangular block made of an imported black stone similar to that of the objects inscribed with this text of Samsī-Addu and the foundation records of Man-ištušu discovered at Sippar; that later text also records work undertaken on Ištar's temple at Nineveh. As suggested by Reade (2000, 75) -- who also adds a further unpublished and not ascribable inscription (1855-12-05, 0104 = BM 104406) to the list of related texts -- the shape, script, and unusual material of Samsī-Addu's foundation records represent a "deliberate attempt to emulate those of Man-ištušu;" the same can be said about the above mentioned text of Aššur-uballiṭ.

This project at Nineveh took place, as the inscription states, after the conquest of the Amorite kingdom Nurrugûm, to which the city belonged, in the eponymy of Aššur-malik (ca. 1780), Samsī-Addu's twenty-ninth regnal year. The restoration of this temple of Ištar, the careful redepositing of Man-ištušu's inscriptions, the writing of texts in archaizing script on imported black stone similar to the one used by Man-ištušu, and the use of similar phrasing (e.g. šar kiššatim) to Sargonic period texts suggest that Samsī-Addu made efforts to ideologically link his kingship to that of Agade, a city in which he lived in before the conquest of Nineveh (Ziegler 2004, 26), and which, according to a recent hypothesis (Charpin 2004, 372-5), might have also been Samsī-Addu's home town.

The fact that not a single foundation document of Man-ištušu has been unearthed from the Ištar temple of Nineveh is worth noting. This may be due to the fact that Assyrian kings after Aššur-uballiṭ made a concerted effort to erase evidence that kings of Agade had once held authority over Nineveh or had worked on the Ištar temple there (Reade 2005, 357; cf. Westenholz 2004); Man-ištušu was therefore not mentioned as a previous builder.

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005646/] of Samsī-Addu I 02.

Commentary

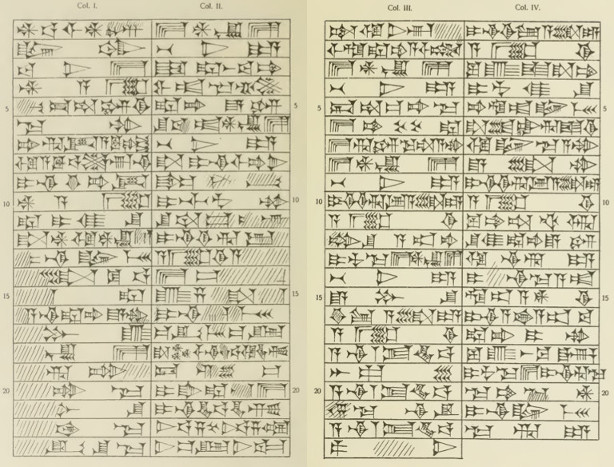

The master text of the online edition presented here follows Grayson, RIMA 1, which generally relies on ex. 1. The exceptions are as follows:

Col. i 1–4 (ex. 1, 9), 5–6 (1, 4), 20–21 (2, 3), 22–23 (2), 24–25 (3, 11);

Col. ii 1 (5), 2 (4–5), 3 (4), 4–5 (4–5), 6 (1, 5), 20–22 (1–2), 23 (2);

Col. iii 2 (4), 3–5 (1, 4), 9 (1, 4), 24 (2), 25 (2, 7), 26 (2, 7, 18);

Col. iv 1 (1, 2), 6 (1, 19), 21—24 (1–3), 25 (2).

Bibliography

03

Two different royal inscriptions are written on a Neo Assyrian tablet from Nineveh; the texts may have been written as part of scribal exercise. The better-preserved obverse contains an inscription of Samsī-Addu I, while the badly damaged reverse preserved part of a text of Ikūnum (text no. 5), as correctly identified by H. Galter. Both inscriptions commemorate construction on a temple of the god Ereškigal, most probably in Aššur, as B. Landsberger (1954, p. 36 n. 34) has suggested.

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005647/] of Samsī-Addu I 03.

K 08805 + K 10238 + K 10888. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Bibliography

04

One of two texts inscribed on the same clay tablet (the other one being text no. 5) found in the Old Babylonian palace at Mari. Like other texts belonging to this ruler and retrieved from similar contexts (nos. 5-7 and 2001-2), this was, as suggested by D. Charpin, a school exercise text. In this case the original inscription must have been engraved on the actual throne described in the text in which Samsī-Addu dedicates a throne of kamiššaru (pear) wood, decorated in gold, to Itūr-Mēr, god of Mari, sometime after the conquest of the city in the eponymy of Haya-malik.

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005648/] of Samsī-Addu I 04.

Bibliography

05

This text was written on the reverse of text no. 4 and like that inscription it probably represents a school exercise. The text is extremely similar, although not identical, to text no. 4. Here, the golden decorated throne that is dedicated to Itūr-Mēr, god of Mari, is made of ebony.

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005649/] of Samsī-Addu I 05.

Bibliography

06

This text was found in the Old Babylonian palace at Mari (like texts nos. 4-5, 7, and 2001-2) and it was probably a school exercise copy of an inscription originally attached to a bronze kettledrum dedicated to Ištar-šarrum (but see, D. Carpin, CDOG 3 [2004] p. 373 n. 13 for a different interpretation).

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005650/] of Samsī-Addu I 06.

Bibliography

07

A tablet found in the Old Babylonian palace at Mari is most likely a school text. The original inscription commemorates the dedication of some "twin" objects to the god Dagan, and it was probably engraved on each of them. D. Charpin has suggested matching the šākultu with the cultic banquet tākultu of later periods (see Adad-nerari I text no. 26-27, and Shalmaneser I text no. 25-27). The "twins" mentioned in the inscription could be identified as large containers or vases similar to those present in Erišum I text no. 1:12.

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005651/] of Samsī-Addu I 07.

Bibliography

08

A clay tablet from Terqa records the construction of a temple for Dagan in that city. The meaning of the name of the temple -- Ekisiga in Sumerian and bīt qūltīšu in Akkadian – has been long discussed, but both dictionaries AHw (p. 927) and CAD (Q p. 302) agree on "His Silent Temple."

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005652/] of Samsī-Addu I 08.

Bibliography

09

This short text was stamped on several clay bricks found at Aššur; they are thought to have originally belonged to the Aššur temple.

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005653/] of Samsī-Addu I 09.

Bibliography

10

The text presented here was inscribed on this monarch's personal seal. It is known from seal impressions found on several clay tablets and envelopes. These were discovered in palaces at both Mari and Acem höyük.

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005654/] of Samsī-Addu I 10.

Bibliography

11

This brief text evidently served as a label for several types of object, as it has been discovered both stamped on several clay bricks and inscribed on stone door sockets and a small precious stone. The precious stone also has a poorly preserved eight-line Sumerian inscription written on it. The legible text (the first two lines) read as follows: dnin-é-an-na nin-a-ni-ir "To the goddess Nin-eanna, his mistress." All of these objects were discovered in the Aššur temple at Aššur.

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005655/] of Samsī-Addu I 11.

Bibliography

12

This proprietary label of the king is preserved on a black and white agate eyestone; only one of his titles is given. The object was found at Khorsabad and is now housed in the Louvre.

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005656/] of Samsī-Addu I 12.

Bibliography

1001

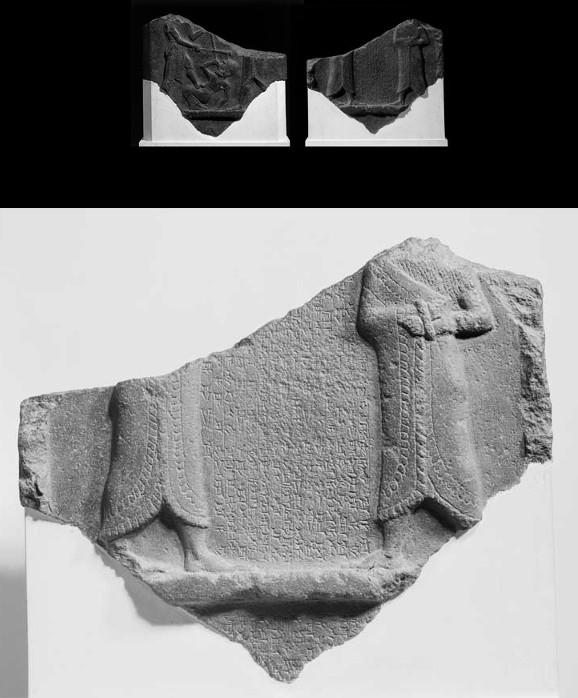

This fragmentary inscription is engraved on a broken relief that was discovered in Mardin or at Sinjar, according to V. Scheil report. Because the name of the ruler who had this object commissioned is completely broken away, there is no scholarly consensus on the identity of the Old Babylonian/Assyrian king to whom the stele belongs. A. Goetze (1952) suggests Daduša of Ešnunna, Nagel (1959) proposes Narām-Sîn of Ešnunna, and W. von Soden (1953), J. Læssøe (1959), and D. Charpin and J.-M. Durand (1985) argue for Samsī-Addu I. The latter suggestion is tentatively followed here, as A.K. Grayson did in RIMA 1.

AO 02776 © Musée du Louvre / Pierre et Maurice Chuzeville

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005657/] of Samsī-Addu I 1001.

Bibliography

2001

A clay tablet found in the Old Babylonian palace in Mari (see also text no. 4-7) bears two dedicatory inscriptions (text nos. 2001 and 2002), both of which are school exercise copies. Each text consists of a name of a cultic lion figurine that was dedicated by Samsī-Addu to the goddess Ištar. The originals are presumed to have been engraved on the figurines themselves, which, according to text no. 2002, were placed Emeurur, most likely a shrine of Ištar in Mari.

The inscribed figurines were made sometime after Samsī-Addu captured Mari, an event that took place in the eponymy of Haya-malik.

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005658/] of Samsī-Addu I 2001.

Bibliography

2002

See introduction to no. 2001.

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005659/] of Samsī-Addu I 2002.

Bibliography

2003

This text has been discovered in the form of seal impressions on several tablets at Mari. The seal itself was the property of Amaduga, "female servant" of Samsī-Addu.

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005660/] of Samsī-Addu I 2003.

Bibliography

2004

The seal of Iamatti-El, "servant" of Samsī-Addu, is known from an impression on a clay tablet found in the Old Babylonian palace at Mari.

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005661/] of Samsī-Addu I 2004.

Bibliography

2005

This text is known from a seal impression on a clay tablet discovered in the Old Babylonian palace at Mari. The seal was once the property of a "servant" of Samsī-Addu, Iaḫuzānum, son of Zamāmu.

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005662/] of Samsī-Addu I 2005.

Bibliography

2006

The text of the inscribed seal of a "servant" of Samsī-Addu -- Ammī-iluna, son of Irra-i-[...] -- is known from an impression on a clay tablet discovered at Mari.

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005663/] of Samsī-Addu I 2006.

Bibliography

2007

This proprietary label is known only in the form of a seal impression on a clay envelope from Mari. The now-lost seal was the originally the property of Samsī-Addu's "servant" Iattiya, son of Samsī-malik.

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005664/] of Samsī-Addu I 2007.

Bibliography

2008

A clay envelope discovered at Mari bears an impression of the seal of [Ia]matti-[El], son of Hata, "servant" of Samsī-Addu (cf. text no. 2004).

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005665/] of Samsī-Addu I 2008.

Bibliography

2009

This text is known from two exemplars, both in the form of seal impressions on clay envelopes; the objects were discovered at Mari. The original seal, which is now lost, was the property of Tarim-š[akim], "servant" of Samsī-Addu.

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005666/] of Samsī-Addu I 2009.

Bibliography

2010

Four tablets from Mari bear an impression of a seal of a "servant" of Samsī-Addu. That seal was once the property of Umannisuta, son of Idin-[...].

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005667/] of Samsī-Addu I 2010.

Bibliography

2011

This text is known from an impression on a clay tablet discovered at Mari. The now-lost seal was the property of Samsī-Addu's "servant" Adad-saga, son of Ḫaziya.

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005668/] of Samsī-Addu I 2011.

Bibliography

2012

The seal of [M]ašiya, son of Šalim, a "servant" of Samsī-Addu, is knowm from a impression on a clay tablet from Mari.

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005669/] of Samsī-Addu I 2012.

Bibliography

2013

Several clay tablets and envelopes unearthed at Tell al Rimah bear seal impressions of a seal that was the property of Lu-Ninsianna, "servant" of Samsī-Addu.

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005670/] of Samsī-Addu I 2013.

Bibliography

2014

The seal of Samsī-Addu's "servant" [Zi]mrī-hammu, son of [S]umu-ammim, is known from impressed clay envelope found at Tell al Rimah. The object is currently housed in the Iraq Museum.

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005671/] of Samsī-Addu I 2014.

Bibliography

2015

Impressions of a seal of a certain D[agan-...], a "servant" of Samsī-Addu, were found on tablets discovered at Tell Leilan, during the 1979 season (led by H. Weiss).

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005672/] of Samsī-Addu I 2015.

Bibliography

2016

This text is known from a seal impression on a clay tablet found at Tell Leilan, in a Building Level II structure. The seal itself, which is now lost, was the property of Samsī-Addu's "servant" Ṣurri-Adad, son of [Z]idriya.

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005673/] of Samsī-Addu I 2016.

Bibliography

2017

A cylinder seal made of haematite now in the Bibliotheque Nationale (Paris) is inscribed with a proprietary label of Ibāl-eraḫ, son of Kiabkurānu, "servant" of Samsī-Addu. The original provenance of the object is unknown.

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005674/] of Samsī-Addu I 2017.

Bibliography

2018

A seal of unknown provenance bears a short proprietary label of Laḫar-abī, the scribe, son of Kakisum, "servant" of Samsī-Addu. The object is currently housed in the Louvre (Paris).

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005675/] of Samsī-Addu I 2018.

Bibliography

2019

A seal of unknown provenance and now in the Louvre in Paris is inscribed with a proprietary label of Samsī-Addu's "servant" Sîn-iqīšam, son of Būr-Adad.

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005676/] of Samsī-Addu I 2019.

Bibliography

2020

A seal of Rīš-ilu, son of Aduanniam, states that this man was a "servant" of Samsī-Addu. The original find spot of the object is not known. The positioning of the signs in the inscription is a little strange: the DUMU sign is oddly placed and the name of the father of the seal's owner (a-du-an-ni-am) is not written in a straight line.

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005677/] of Samsī-Addu I 2020.

Bibliography

2021

A seal of unknown provenance bears a short proprietary label of Pazaia, son of Aḫi-šakim, "servant" of Samsī-Addu.

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005678/] of Samsī-Addu I 2021.

Bibliography

2022

A seal once belonging to Samsī-Addu's "servant" Kunnat[um], son of Mezi-[...], was acquired by J.C. Rich during his travels in the Middle East and the Joanneum in Graz, where it is still housed.

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005679/] of Samsī-Addu I 2022.

Bibliography

2023

This text is known from the seal of Samiya, son of Ḫani-m[alik], a "servant" of an Old Assyrian king. While the full name of the monarch in question is not preserved, the orthography of the beginning of the name suggests that the text should be attributed to the reign of Samsī-Addu I.

Access the composite text [/riao/ria1/Q005680/] of Samsī-Addu I 2023.

Bibliography

Nathan Morello & Poppy Tushingham

Nathan Morello & Poppy Tushingham, 'Inscriptions', RIA 1: Inscriptions from the Origins of Assyria to Arik-dīn-ili, The RIA Project, 2023 [http://oracc.org/oldassyrianperiod/samsiaddudynasty/samsiaddui/inscriptions/]