Temple staff

The officials of Nabu's temple Ezida ran its daily affairs, ensuring a regular supply of offerings and gifts. The "mayor" TT of Ezida oversaw the annual akītu TT ritual TT between god and king.

Our evidence for temple affairs comes from three different sets of documents:

- the letters sent from priests in Kalhu to king Esarhaddon PGP in Nineveh PGP ;

- legal documents from the reign of Assurbanipal PGP and later, found in the temple;

- and hymns that were performed during major rituals.

Together they allow us to paint a partial portrait of the men (and it was almost exclusively men) who staffed Ezida in the 7th century BC.

Royal liaison officers: the hazannu and qēpu

Image 1. The hazannu Nadinu writes to request an audience with king Esarhaddon (SAA 13: 080). British Museum 1883-01-18, 43. View large image on British Museum website. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

The hazannu (literally "mayor") served as a link between temple and court, ensuring that nothing of consequence escaped the king's scrutiny. We know the name of only one of these officials:

- Nabu-šumu-iddina PGP

- King Esarhaddon's PGP hazannu, known as Nadinu for short, wrote regularly to him and to crown prince TT Assurbanipal. His letters reveal, perhaps surprisingly, that he was not an intimate of the king and even to catch a glimpse of him was a once-in-a-lifetime event (SAA 13: 80, Image 1). Perhaps just as unexpectedly, Nadinu was not always resident at Kalhu but was at least present to oversee the annual akītu ritual, in which Nabu PGP and Tašmetu PGP got together each spring (SAA 13: 79).

- To modern sensibilities it may seem surprising that most of the hazannu's letters comprise daily reports on horses for the army that have arrived in Kalhu from provinces all over the empire (SAA 13: 82-123). We do not yet know what, if anything, these reporting duties had to do with Nadinu's role as overseer of Nabu's temple.

A hazannu of Kalhu also witnesses two votive donations to Ezida in the late 7th century (SAA 12: 96-97). His name is not preserved.

The qēpu official served a similar function, it seems. At least in the late 7th century, a single qēpu was the royal delegate to the temples of Nabu and Ninurta together (SAA 12: 96).

The cultic personnel

The chief priest, or šangû was, as the name suggests, the head of the cultic staff of the temple. We know the names of several men who held this post in the 7th century BC. Others also write to the king about ritual matters in the temple, suggesting that they too had priestly appointments of some sort, even if we don't know what they were. Most of the time, the letter-writers just tell the king that "I", "we" or "they" will perform particular ritual actions.

- Marduk-šarru(?)-uṣur(?) PGP , šangû

- This man witnessed loans on Nabu's behalf and a votive TT donation to Ninurta's temple, in 638* TT BC and 621* TT BC (SAA 12: 92, 96)

- Nabu-kudurri-uṣur PGP

- Reported to the king on a ritual for Tašmetu (SAA 13: 130).

- Nergal-šarrani PGP

- Wrote several letters to Esarhaddon and to the queen mother TT , mostly about the progress of the akītu and other rituals, but also to request treatment for an illness he was suffering (SAA 13: 70-77).

- Nabu-šumu-uṣur PGP , šangû

- Involved in many loans on Nabu's behalf, as borrower, lender and witness, in the years 661–655 BC, 638* TT , 637* TT , 634* TT , 623* TT , 622* TT 616* TT (1); (SAA 12: 92–95)

- Urad-Ištar PGP , šangû

- Witnessed a temple loan taken out by a member of the queen's guard (2)).

- Urad-Nabu PGP

- Wrote to king Esarhaddon about the akītu and other rituals, on making statues of the king for the temples, and to request an āšipu and an asû-healer when he is sick (SAA 13: 56–69). Priests from the temple of Ninurta accuse him of stealing land and people from them for his own temple, by drawing up a false legal document (SAA 13: 126).

The scholars

The large collection of learned writings in the room opposite Nabu's shrine already suggests that scholars TT , especially āšipu-healers, were associated with the Ezida temple. But no explicit link is made in the texts themselves. However, we know that Nabu's temple in Dur-Šarruken PGP was staffed with an āšipu, who was given regular provisions (SAA 1: 129).

The letters of the royal scholars associated with the Kalhu Ezida suggest that they spent at least some of their time away in Nineveh. However, the priest Nergal-šarrani PGP reassures king Esarhaddon that the senior āšipu Adad-šumu-uṣur will be treating an outbreak of fungus in the temple (SAA 13: 71). Coincidentally or not, one of the scholarly tablets TT found in the Ezida is precisely a series of omens on the portentous significance of fungi (CTN 4: 36).

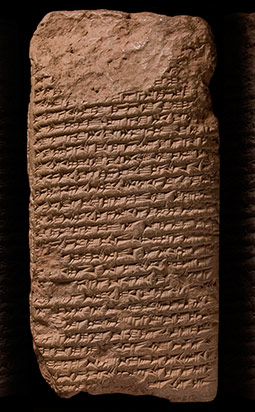

We have much clearer evidence for the activities of kalû-lamenters in Kalhu. Some time in the 8th century, a galamahhû ("chief lamenter") (whose name is now missing) dedicated a grey stone offering bowl to the temple (Image 2). Carved on its surface is a depiction of a ritual perfomer, presumably the galamahhû himself, in a tall conical hat.

During the reign of Esarhaddon, the kalû Pulu PGP writes to the king whenever he finds malformed kidneys in sacrificial sheep, fearing they may portend ill (SAA 13: 131, 133). However, as far as bārû-diviners were concerned, kidneys had no ominous significance.

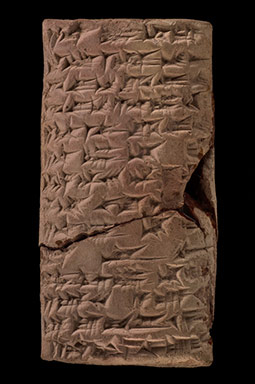

On that evidence alone, it would appear that Pulu was highly conscientious. However, a colleague or rival — whose name is frustratingly missing — denounces Pulu to the king (SAA 13: 134, Image 3). Not only has he been remodelling the fixtures and fittings in Ezida but he has updated lots of the rituals too and appointed new staff. At the end of the letter, though, there is a hint that this report comes from the son of the man Pulu has replaced — and that this is all part of a smear campaign to oust Pulu in the letter-writer's favour.

The temple also had at least one scholar who knew how to calculate calendars. Urad-Nabu PGP —perhaps the same man mentioned above—reports to the king of a visit from noblemen of the cities of Babylon and Borsippa who have come to ask for advice on working out when to add an extra lunar month to the year (SAA 13: 60). This was necessary in order to keep the lunar calendar of twelve 29 or 30-day months aligned with the 365-day solar year so that rituals could be performed at the correct time.

The domestic staff

The domestic staff of the temple were probably not cuneiform TT literate, and certainly did not have the status or presumption to write to the king. Therefore we know about them through the letters of more senior personnel and, especially in later times, from witness lists on temple legal documents.

Pulu's denouncer is particularly helpful in this regard (SAA 13: 134). He mentions "a woman who carries out the lighting ceremony for the goddess Tašmetu", an "eye-opener" (who presumably looked after the divine statues) and a goldsmith, as well as an āšipu-healer (Image 3).

The following men with temple-related job titles appear amongst the witnesses of loans and other legal documents drawn up in the late 7th-century Ezida (4); (SAA 12: 92, 95, 96):

- Gallulu PGP , Nabu-ahhe-eriba PGP , Nani PGP

- These three men all take the title lahhinu Nabu "steward of Nabu"

- Urdu PGP

- Frequently called on to witness legal documents, his full title was "(household) cook of Nabu's temple"

- Nabu-ahu-iddina PGP

- (Chief) firewood supplier of Nabu's temple

- Dayai PGP

- Gatekeeper

- Nabu-kibsi-uṣur PGP

- Store keeper, exact title missing

- Balaṭi PGP , Nabu-naʾid PGP

- Domestic staff with missing titles

- (name now missing)

- Chief musician of Nabu's temple

The slaves and votives

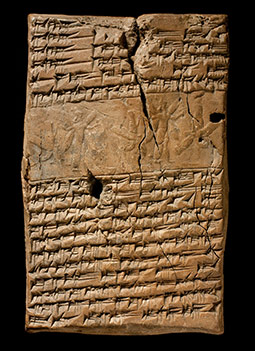

Image 4. Record of the donation of a slave named Dur-maki-Issar to the god Ninurta's temple in Kalhu (SAA 12: 92). British Museum K.382. View large image on British Museum website. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Finally, we must not forget the men, women and children who were given to Nabu's temple by legal deed (Image 4). Such donations could be a generous act of piety and loyalty — for instance the gift of two slaves (Lul[...] PGP and Palhu-ušezib PGP ) and a large tract of land "for the preservation of the life of Sin-šarru-iškun PGP , king of Assyria, his lord, and the preservation of the life of his queen" (SAA 12: 96).

At the other end of the socio-economic scale it could also be a sign of economic desperation. One man gives his (dead or destitute?) sister's sons, Urad-Ištar PGP and Nabu-hamatua PGP ; these were mouths that could not otherwise be fed (SAA 12: 95). But whatever the circumstances of the gift, the donor could be sure that temple would feed and house the votives TT , as well as putting them to work for a higher good.

Content last modified: 18 Dec 2019.

References

- Parker, B. 1957. "Nimrud tablets, 1956: economic and legal texts from the Nabu Temple", Iraq 19, pp. 125-138 (PDF available via JSTOR for subscribers), pp. ND 5460, 5450, 2314, 2307, 2308, 5428, 2334. (Find in text ^)

- Parker, B. 1957. "Nimrud tablets, 1956: economic and legal texts from the Nabu Temple", Iraq 19, pp. 125-138 (PDF available via JSTOR for subscribers), pp. 128, ND 5448. (Find in text ^)

- Mallowan, M.E.L., 1966. Nimrud and Its Remains, vols. I-II, London: Collins, pp. 270, figure 251. (Find in text ^)

- Parker, B. 1957. "Nimrud tablets, 1956: economic and legal texts from the Nabu Temple", Iraq 19, pp. 125-138 (PDF available via JSTOR for subscribers). (Find in text ^)

Eleanor Robson

Eleanor Robson, 'Temple staff', Nimrud: Materialities of Assyrian Knowledge Production, The Nimrud Project at Oracc.org, 2019 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/nimrud/ancientkalhu/thepeople/templestaff/]