Scholarly families

Two different scribal TT families dominated intellectual activity in ancient Kalhu. The Ištaran-šumu-ukin family produced several generations of royal scribes and royal āšipu-healers in the 9th and 8th centuries BC. Members of the Gabbu-ilani-ereš family also served as royal scholars TT . They became particularly prominent in the late 8th and early 7th century when Nabu-zuqup-kenu and his descendants took many senior roles at court.

Patronage and descent

The king did not issue royal scholars with formal contracts of employment but instead patronised them with gifts and favours in return for their loyalty and expertise. In this way intimate relationships of trust built up, which could be passed on through the family, both from king to crown prince TT and from scholar to apprentice. Fathers and uncles trained sons and nephews, not only in the reading and production of learned texts but also in the performance of royal ritual TT and appropriate conduct at court. Likewise, princes learned from kings which courtly scholars to respect and reward, and which to disfavour or even expel.

In this way, veritable dynasties of scholars dominated Assyrian court circles for generations at a time. We do not know how they first gained favour, or how they fell from grace, but we can track some of their activities through their letters and library tablets TT .

The descendants of Ištaran-šumu-ukin

About 30 scholarly tablets from Ezida, Nabu's temple in Kalhu, end with colophons TT , short notes about who wrote or copied them, and why they did so. These colophons tell us that in the 9th and early 8th century BC, scholarship in Ezida and the royal court was dominated by several generations of the descendants of Ištaran-šumu-ukin PGP , an āšip šarri ("royal exorcist") who may have lived in the 10th century BC.

- Ištaran-mudammiq PGP

- Ištaran-mudammiq was šaggamaḫḫu ("senior exorcist") of king Assurnasirpal II. He was the son of Tappuya PGP , a šatammu ("temple administrator") from the northern Babylonian city of Der PGP , and grandson of another šatammu, Huzalu PGP . Ištaran-mudammiq owned an ominous calendar for the month of Tašritu TT (CTN 4: 58). The text is duplicated exactly, even down to the colophon, on a tablet found in the so-called āšipus' house in 7th-century Assur PGP .

- Babilayu PGP , son of Nabu-mudammiq PGP

- Ištaran-mudammiq had a grandson (whose name is missing). He was the owner or copyist of a compendium of incantations TT called Utukkū lemnūtu "Evil demons" (CTN 4: 103).

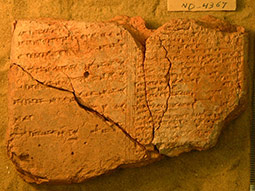

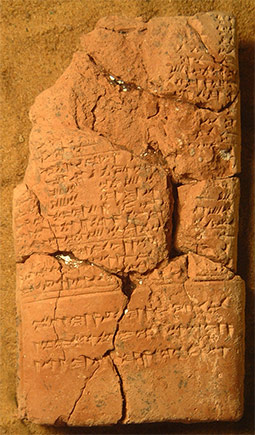

- Marduk-[...] PGP (Image 1)

- Ištaran-mudammiq's great-grandson was the ṭupšar šarri ("royal scribe") and ummânu ("expert/scholar") of king Adad-nerari III PGP (r. 811-783 BC). His father was the āšip šarri Babilayu PGP son of Nabu-mudammiq PGP (who may or may not have written CTN 4: 103, above). Marduk-[...] owned of a tablet of the celestial TT omen TT series Enūma Anu Ellil TT (CTN 4: 8), dated 787 BC.

Over the generations, this family changed the way they identified their origins. Ištaran-mudammiq presents himself as a newcomer, with roots in the temple administration of the northern Babylonian city of Der. But by his great-grandson's time the primary ancestor is a royal scholar, the otherwise unattested Ištaran-šumu-ukin. We cannot know whether Ištaran-šumu-ukin was from the same genealogical line as Tappuya and Huzalu, or represents another branch of the family (although his name suggests that he too was from Der). What matters is that by the early 8th century, after four generations of royal service, these scholars saw themselves as always having been royal courtiers.

Sadly, that is all we know for certain about these men, although it is tempting to speculate that Marduk-[...] was involved in the rebuilding of Nabu's temple that took place during the reign of his king Adad-nerari III.

The descendants of Gabbu-ilani-ereš

By the late 8th century, it appears that the Ištaran-šumu-ukin family had been ousted or superseded as foremost court scholars by the descendants of Gabbu-ilani-ereš PGP . This man had served as ummânu to both Tukulti-Ninurta II PGP (r. 890-884 BC) in Assur PGP and then Assurnasirpal II in Kalhu. He was thus Ištaran-mudammiq's contemporary. He may have been responsible for the wording of some or all of Assurnasirpal's building inscriptions at Kalhu.

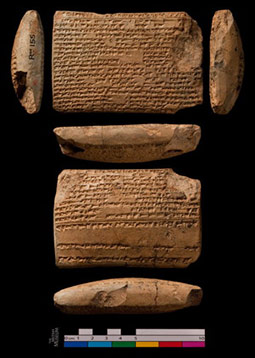

- Nabu-zuqup-kenu PGP (Image 2)

- Perhaps the most famous of Gabbu-ilani-ereš's descendants, both then and now, was Nabu-zuqup-kenu. He served as chief scribe to kings Sargon II PGP and Sennacherib PGP and wrote over 60 surviving scholarly tablets. Nearly two-thirds of these explicitly state that they were written in Kalhu (2). However, the tablets themselves belong to the Kuyunjik collection TT of the British Museum TT , most likely meaning that they were excavated by Layard PGP and his associates from the royal citadel TT of Nineveh PGP . We cannot prove that he was directly involved in tablet production for Nabu's temple.

- However, several of Nabu-zuqup-kenu's descendants wrote scholarly tablets which were excavated from the Kalhu Ezida in the 1950s:

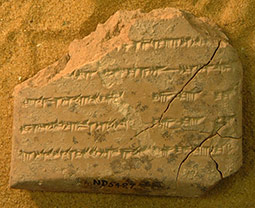

- Adad-šumu-uṣur PGP (Image 3)

- Nabu-zuqup-kenu's son was chief āšipu of king Esarhaddon PGP . He was owner of a tablet from the terrestrial omen TT series Šumma ālu ("If a city (is set on a height)") (CTN 4: 45).

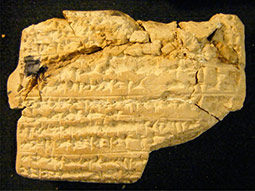

- Šumaya(?) PGP (Image 4)

- Adad-šumu-uṣur's nephew (name missing but possibly Šumaya), the son of his brother Nabu-zeru-lešir PGP (?), Esarhaddon's chief scribe. This man was copyist of an ominous calendar (CTN 4: 59) "for the prolongation of his life".

- Further sons or descendants of Nabu-zuqup-kenu are mentioned in colophons of two tablets of physiognomic omens Alandimmû and another of unidentified omens (CTN 4: 74, 78, 89).

- Nabu-leʾi PGP (Image 5)

- Son of Adad-šumu-uṣur's close associate, Esarhaddon's chief lamenter TT Urad-Ea PGP , was the scribe of an as yet unidentified ritual (CTN 4: 187), which he "copied like its original for him to see".

Adad-šumu-uṣur and Nabu-zeru-lešir are well known in Assyrian court correspondence from Nineveh, sometimes in collaboration with Urad-Ea and other colleagues. These letters tell us that Adad-šumu-uṣur also worked at Kalhu, where he performed a ritual against two types of fungi that had infested Ezida (SAA 13: 71).

Šumaya son of Nabu-zeru-lešir is attested as an āšipu at Nineveh late in Esarhaddon's reign (SAA 10: 257, 291). Some time in 671–669 BC he petitioned crown prince Assurbanipal to let him take over his dead father's scholarly work at Kalhu, having established himself in a similar role in Tarbiṣu PGP (SAA 16: 34). He and Adad-šumu-uṣur witnessed a legal document together in the northern Assyrian town of Ispallure PGP in 666 BC (SAA 6: 314).

One of Adad-šumu-uṣur's sons was the infamous Urad-Gula PGP , who was expelled from court service as an āšipu never to return, despite his influential father's repeated pleas for clemency (SAA 10: 224, 226, 294). Perhaps he spent time in Kalhu; we do not know.

The Gabbu-ilani-ereš family disappear from the written record during the reign of Assurbanipal, along with all other court scholars.

A scholar without family

The only other well documented scholar in Nabu's temple conspicuously never mentions his family.

- Banunu PGP

- An āšipu, Banunu PGP was copyist and/or owner of four scholarly tablets:

- a prayer of divination "from a Babylonian original" (CTN 4: 61);

- the ritual Mīs pî ("mouth opening") (CTN 4: 188);

- medical recipes (CTN 4: 188);

- and the medical plant list Uruanna (CTN 4: 192).

In the colophons of the second and third of these tablets Banunu exclaims:

Do not disperse the gerginakku ("library"); taboo of Ea PGP , king of the Apsu TT !

In in the aftermath of Assurbanipal's conquest of Babylonia PGP , a man named Banunu was assigned to overee of the governor TT of Nippur PGP 's son in Nineveh (SAA 11: 156, (3)). It is possible, but not certain, that this is the same person.

Content last modified: 18 Dec 2019

References

- Guinan, A., 2002. "A severed head laughed: stories of divinatory interpretation", in L.J. Ciraolo and J. Seidel (eds.), Magic and Divination in the Ancient World (Ancient Magic and Divination, 2), Leiden: Brill-Styx, pp. 7-40. (Find in text ^)

- Hunger, H., 1968. Babylonische und assyrische Kolophone (Alter Orient und Altes Testament 2), Kevelaer: Butzon & Bercker; Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, pp. 90–95, nos. 293–311, of which nos. 293–294 and 305 name Kalhu. (Find in text ^)

- Parpola, S., 1983. "Assyrian library records", Journal of Near Eastern Studies 42, pp. 1–29 (PDF available via JSTOR for subscribers). (Find in text ^)

Eleanor Robson

Eleanor Robson, 'Scholarly families', Nimrud: Materialities of Assyrian Knowledge Production, The Nimrud Project at Oracc.org, 2019 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/nimrud/ancientkalhu/thepeople/scholarlyfamilies/]