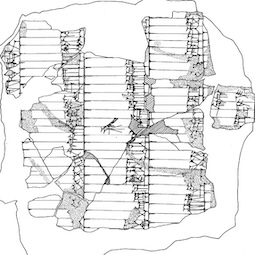

Babylonian Home Schooling at Tell Ingharra (Trench C)

To explore the stratigraphy of Tell Ingharra, the OFME dug a series of deep trenches in front of the northwest entrance of the Temple of Ishtar between 1927 and 1932, collectively known as Trench C (see Figure 1). This area yielded numerous cuneiform tablets from the Old Akkadian, Old Babylonian and Neo-Babylonian periods, including letters, contracts, and accounts, but also exercises written in the course of home-schooling during the Old Babylonian period (Ohgama and Robson 2010: 216–22).

[/kish/images/trenchc-large.jpg]

[/kish/images/trenchc-large.jpg]1. Overview of Trenches C9 to C-15, excavated in 1931-32. Trenches C-6 to C-8, dug in previous years, ran parallel to Trench C-9 and were later cut into by soundings YW and YWN. Source: Iraqi State Board of Antiquities and Heritage, May 2024.

We do not know the exact archaeological contexts of the Trench C finds, due to the rough and ready methods used to excavate the area. However, the tablets were assigned trench numbers, which give us a vague idea of which tablets might have been excavated together. However, since the trenches were so enormous, up to 5 metres wide and deep, the same trench numbers might have been assigned to tablets which do not belong together at all. Equally, it is quite possible that apparently distinct lots of tablets might actually cross the trench boundaries and thus belong together.

Nevertheless, Naoko Ohgama and Eleanor Robson (2010) were able to identify three very different groups of tablets.

Trenches C-8, C-10 and C-11 produced sixteen very elementary school exercises, mostly 2-3 line extracts from lists of cuneiform signs, simple words and phrases in Sumerian, and basic arithmetic and geometry. Most of these tablets had both the teacher's version and the student's attempt at copying them. Evidence from other ancient Babylonian cities, such as Nippur and Sippar, shows that it wasn't just scribal students who learned exercises like this: many different types of people wanted to learn the basics of how to read, and calculate in cuneiform.

- View the texts from Trench C-8 [/kish/trench-c8] in the Oracc Kish corpus

- View the texts from Trench C-10 [/kish/trench-c10] in the Oracc Kish corpus

- View the texts from Trench C-11 [/kish/trench-c11] in the Oracc Kish corpus

[/kish/images/ash1931-184o.jpg]

[/kish/images/ash1931-184o.jpg]2. A scale drawing of the front side of a very damaged cuneiform tablet found in Trench C-8, on measuring about 20 x 19 cm. It contains a simple, standardised exercise in writing basic cuneiform signs which is now known as Syllabary A. Source: Ashmolean 1924.184 (Ohgama and Robson 2010: 232, no. 6).

In Trench C-15 by contrast, the OFME archaeologists had found evidence of more advanced schooling in cuneiform culture, as well as elementary exercises. They included long passages from three Sumerian literary works that were often assigned to scribal students across Babylonia in the 18th century BC: a simple hymn to the patron goddess of scribes, Nisaba (ETCSL 2.5.1.5); a humorous tale about the hero Gilgamesh and his friend Enkidu in the cedar forests of Lebanon (ETCSL 1.8.1.5 [https://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.1.8.1.5#]); and some fatherly wisdom supposedly handed down to the mythical flood hero by his father, king Shuruppag (ETCSL 5.6.1 [https://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.5.6.1#]).

- View the texts from Trench C-15 [/kish/trench-c15] in the Oracc Kish corpus

Most interestingly, Trenches C-6 to C-8 produced about 13 tablets containing works of Sumerian literature and ritual which modern scholars have found very difficult to translate so far. Some are in the so-called Emesal version of Sumerian, which was used for lamentation and mourning. Others are even harder for us to read because they use spellings which seem to be unique to this part of Kish. The legal contracts found in the same trenches date to the late 19th and early 18th centuries BC, at least a generation earlier than the school tablets.

- View the texts from Trench C-6 [/kish/trench-c6] in the Oracc Kish corpus

- View the texts from Trench C-7 [/kish/trench-c7] in the Oracc Kish corpus

- View the texts from Trench C-8 [/kish/trench-c8] in the Oracc Kish corpus

Excavations at other sites in southern Iraq have shown that there were no dedicated school buildings in Babylonia, just as in many other pre-modern societies (Robson 2025). Instead, schooling took place wherever a teacher and students came together, whether in a home or a corner of an institutional building such as a temple or palace. All they needed were light and shade to read by — so courtyards were preferred locations for education — and a container of water to keep their tablet clay damp for writing and recycling. Neither teaching nor learning were full-time occupations either, but were fitted in between earning a living, typically by priests and healers, surveyors and scribes. It is highly likely that this was the case in Kish and Hursagkalama too. The tablets from Trenches C-6 to C-8, for instance, might have belonged to an apprentice lamentation priest who served the nearby temple of Ishtar.

11 Sep 2025

Nadia Aït Saïd-Ghanem & Eleanor Robson

Nadia Aït Saïd-Ghanem & Eleanor Robson, 'Babylonian Home Schooling at Tell Ingharra (Trench C)', The Forgotten City of Kish • مدينة كيش المنسية, The Kish Project, 2025 [http://oracc.org/MoundsofKish/TellIngharra/TrenchC/]