The Temple of Ishtar on Tell Ingharra

The monumental building located a few steps away from the main entrance to Tell Ingharra was once a temple of the great goddess Ishtar [https://oracc.org/amgg/Listofdeities/InanaIshtar/index.html] (Figure 1). In ancient Iraq, temples were not only holy places in which gods and goddesses were worshipped but also their homes (bītu in Akkadian; É in Sumerian). The gods were physically present in temples, represented as statues placed inside, where humans looked after them. Ishtar's home at Kish had the Sumerian name E-hursag-kalama, "House, Mountain of the Land" (George 1993: 101, no. 482).

How do we know what this building is?

We know that the visible version of this temple was built during the Neo-Babylonian period (612-539 BCE). Assyriologist Stephen Langdon identified it as the goddess Ishtar's temple in 1929, based on evidence from cuneiform texts (Moorey 1978: 84). Five years earlier, Langdon had worked out that Tell Ingharra was ancient Hursagkalama, and he knew that a temple dedicated to her was located here. A Neo-Babylonian poem speaks of Ishtar as "the Lady of Hursagkalama" for example (Thureau-Dangin 1936: 109, AO 18589:16). The Law Code of Hammurabi also records a temple of the goddess Ishtar at Hursagkalama in 1750 BC, over a thousand years earlier. In fact the earliest textual evidence for a temple named E-Hursagkalama dates back to the late third millennium BCE.

Over the many years of the exploration of Tell Ingharra, archaeologists have regularly found the remains of houses and graves around the temple, close to ground level, at a depth of about 1 metre. Some archaeologists believe this means that the temple area may have ceased to be a religious centre in the late sixth or early fifth century BC, possibly after king Xerxes' sack of Babylon in 482 BC (Moorey 1978: 84-85). However, cuneiform tablets from the Temple of Zababa, on Tell Uhaimir, show that temple functionaries were still active at Kish under Xerxes son Artaxerxes I (464–424 BCE) (Hackl 2018:166). It is possible, then, that there was a continuous tradition of worshipping Ishtar here for almost two thousand years.

Who built the temple of Ishtar?

In ancient Iraq, it was the king's duty to build and look after new temples and to restore older ones. Because these buildings were made of a mix of sun-dried and kiln-baked bricks, repairs were part of the natural cycle of life. It was usual to rebuild temples on existing consecrated ground, so a much earlier temple had existed on the same spot (see below). But we cannot be entirely sure if this building had also been dedicated to Ishtar or belonged to some other deity, while she was worshipped elsewhere in the city.

We don't even know which king ordered the building of the Neo-Babylonian version of the temple. There are two possibilities: Nebuchadnezzar II, king of Babylon in 605-562 BC, or Nabonidus, the last king of Babylon in 555-539 BC. Archaeologists have found stamped bricks that bear the inscriptions of both kings around the temple, but not inside it (Moorey 1978: 84, notes 19-20).

Of the two kings, who was the builder? Assyriologists have collected over 130 different building inscriptions of Nebuchadnezzar II and 70 of Nabonidus, but none of them lists this temple. Perhaps this is because the temple was never finished, but we know that building inscriptions could be written even before construction work began, as with inscriptions about Sennacherib's Southwest Palace in Nineveh (Frahm 2008: 15).

The temple's unfinished state became apparent in 1926, when the OFME discovered bricks stacked on top of each other in some of the temple's chambers. De Genouillac had found similar stacks in 1912. The bricks must have been left there by ancient builders to finish or repair the temple, perhaps to act as foundation packing or buttressing (Moorey 1978: 84). But what could have interrupted the builders' work?

If the temple was under construction during the reign of Nabonidus, work probably had to stop because of war. In 539 BCE, the army of Persian king Cyrus the Great won a decisive battle against Babylonia at the city of Opis, about 70 km north of Kish, and then entered Babylon. This victory not only put an end to Nabonidus' reign but also to the Neo-Babylonian Empire. The Persian kings had no interest in supporting Babylonian religious institutions, except as a source of tax income. From their point of view, it would not have been worth investing in a half-built temple.

Architecture

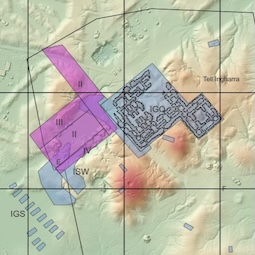

This temple is monumental in size. If you are ever able to visit the temple of Ishtar in person, look at a compass as you walk: you will see that the corners of the temple are orientated toward the four cardinal points (Langdon and Watelin 1930: 1). Its surviving facade is set to the northwest. As you can see from the elevation map below, the temple is square shaped and it is set between Tell Ingharra's two ziggurats, a large one on its southwest side, and a smaller one on its southeast. Because the ziggurats were built much earlier than the version of the temple we see today, the Neo-Babylonian builders had to cut deep into both ziggurats to lay the temple's foundations (Langdon and Watelin 1930: 5).

The temple also hides another temple on its eastern side, a wing probably built earlier than its larger twin. This eastern wing is much smaller, and its internal organisation seems to be a replica of the larger square (Figure 3, Figure 4).

Part of this eastern wing can still be visited today. As you walk toward the northwestern facade, turn to your left and walk along until you reach the facade's corner. There, turn right and climb on the small elevations before you. These are spoil heaps made by the excavators in the 1920s when they cleared trenches. In a few minutes, you will see the walls of the small temple, still partially standing. This eastern wing was discovered by Henri de Genouillac's team in 1912. When the OFME arrived at Kish a decade later, they decided to continue work where de Genouillac had stopped, and soon found the much larger structure attached.

When Charles Watelin and his team finally exposed the temple in 1927, they could see more than one entrance, as well as the general temple layout. There was a central court, as well as a shrine on the south-west side, where priests had worshipped a statue of the god or goddess of the temple. But the northern corner of the temple had already been destroyed when it was found, probably washed away by rain (Langdon and Watelin 1930: 5) (Figure 5).

Conserving the Northwestern Facade of the Temple

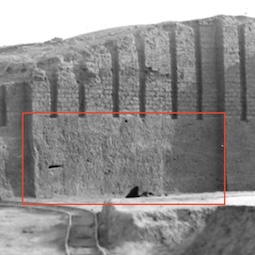

If you visit the temple before SBAH's current restoration work is finished, you will see that the walls of the northwestern facade have preserved part of their shape. They are very damaged now, but their design is clearer in old photographs (see Figure 2). The walls were built in grooves and recesses (Langdon and Watelin 1930: 10), which makes the walls look like columns from afar, a shape we would associate now with a Kitkat chocolate bar. But the bricks at the base look very new (see red arrows in Figure 6). These bricks are not original. SBAH put them there in the late 1970s to strengthen the foundation. Why were they needed?

When Watelin cleared out some of the chambers, he and his team searched for the temple's floor. But then the team decided to dig further down to examine what was underneath, and found walls running 5 metres below the foundation. These belonged to an older structure on top of which the Neo-Babylonian temple had been built. This older building is probably the earlier temple, erected when the ziggurats were built in the Early Dynastic period two thousand years earlier, then dismantled by later builders when they rebuilt on top of it (Langdon and Watelin 1930; Moorey 1978: 88 note 28).

Watelin and Langdon were so excited by this discovery that they decided to completely destroy the Neo-Babylonian temple they had just found in order to expose the earlier version. Langdon, as Director of the Expedition, wrote in his report that: "This building [...] must be destroyed in order to excavate the long series of the older constructions below. It will be preserved for future generations only in the pages and plates of this volume." (Langdon and Watelin 1930: III).

As part of their project, Watelin's team cleared the base of the temple to expose the ground below floor level (see the area marked in red in Figure 7). But the OFME ran out of money in 1932. The following year Iraq finally became independent, and the Expedition never came back. These events saved the temple. However, its foundations and the ground below them were left unprotected. Over time, this area eroded fast. The winds and rain which visit Tell Ingharra every year are strong, and the temple is on top of a hill. This is why SBAH had to reinforce this disappearing ground with newer clay bricks.

The temple of Ishtar was fully brought out of the ground almost one hundred years ago, and it is unfortunately the only earthen structure out of the four unearthed by the OFME which still survives on Tell Ingharra. Under the British Mandate, excavations were permitted, but they did not include plans for the preservation and protection of buildings discovered. In the history of archaeology in the Middle East, such plans would come much later.

04 Jul 2025

Nadia Aït Saïd-Ghanem

Nadia Aït Saïd-Ghanem, 'The Temple of Ishtar on Tell Ingharra', The Forgotten City of Kish • مدينة كيش المنسية, The Kish Project, 2025 [http://oracc.org/MoundsofKish/TellIngharra/TempleofIshtar/]