Sassanian Villas or Palaces (Mounds G–H)

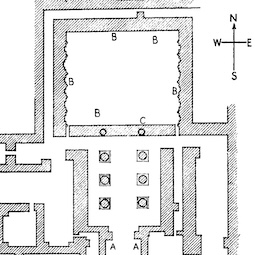

Throughout the centuries, the occupants of Kish were ruled by many different kingdoms and dynasties. During the Sassanian period (226–651 AD), some of its inhabitants built seven large villas or palaces, richly decorated with stucco plaques. These spectacular buildings were unearthed by the OFME between 1931 and 1933, during their final three seasons at Kish. They were located on Mounds G and H, to the east of Tell Ingharra, though little remains of them on the site today (Figure 1).

[/kish/images/sass-fig1-large.png]

[/kish/images/sass-fig1-large.png]1. Map of Mounds G and H, showing the location of the Sassanian villas. Source: State Board of Antiquities and Heritage, May 2024.

Funding the excavation

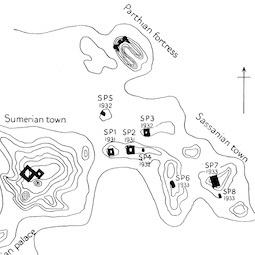

The first three palaces were discovered in the OFME's ninth season. They were remarkable for both their architecture and their stucco decoration. The first palace to be excavated, at the western-most end of the mound, contained two small ornamental pools. Just 40 metres away, a second palace also had two small pools, and may have been part of the same complex (Kawami 2023: 117).

These finds were so outstanding that The Illustrated London News published a double-page spread with photographs, based on an interview Langdon had given to the British newspaper The Daily Telegraph (Lerner 2016: 197; Kawami 2023: 126) (Figure 2).

[/kish/images/sass-fig2-large.png]

[/kish/images/sass-fig2-large.png]2. "Kish Stuccos": full page spread in The Illustrated London News, 14 February 1931 (click or tap to see full image).

In turn, this article attracted the attention of art historian Arthur Upham Pope, an expert on Persian art who had founded the American Institute for Persian Art and Archaeology in New York in 1928. Pope was studying similar stuccos and believed that those at Kish represented a major development in Islamic ornament (Lerner 2016: 197). Langdon was not interested in this post-cuneiform period, and the OFME was running out of money. So he made Pope an offer. He would give the American Institute the rights to excavate Mound H in return for funds. The OFME staff would remain part of the excavation, but specialists like Pope and David Talbot Rice would join the team (Lerner 2016: 196-7).

The American Institute's trustees were hesitant to raise funds for this project, for they did not like Watelin's old-fashioned excavation methods. But Pope managed to enlist the philanthropist Bettie Fleischmann-Holmes (1871-1941) to fund the 1932-1933 excavations. These would be the last seasons of the OFME at Kish.

Stucco decorations

The discoveries which first attracted all this attention were the three residences discovered in 1931 at Mound H. The OFME had opened a few trenches on this mound in previous years, but the full exploration began from the end of 1930. By March 1933, they had found seven palaces or villas, all richly decorated with stucco plaques, many of them fragmentary (Gibson 1972: 77).

These stucco decorations have many different designs. Some are geometric, for example circular rosettes, while others represent flowers or fruits, such as tulips, grapes, and pomegranates (Figure 2).

Other plaques represent humans. Palace 2 was especially surprising in this respect. In this building's square court, twelve life-size male busts in royal apparel were found mounted on the walls, between 14 half-columns (Kawami 2023:118; Moorey 1978: 135) (Figure 3).

Some stucco plaques represented women, and these may have marked the entrance of female apartments (Moorey 1978: 126) (Figure 4).

[/kish/images/sass-fig9-large.png]

[/kish/images/sass-fig9-large.png]4. Crowned Female Head (Field Museum 236322b). Source: Kawami 2023:149

There were animals too, including a lion attacking a bull (Figure 2).

Although the plaques and fragments discovered no longer showed any colour, later researchers detected pigments of yellow, red, and blue (Kawami 2023:192). Unfortunately, Watelin kept only vague records, so it is impossible to restore the original scheme and location of the decorations.

Most of the stuccos were sent to the Field Museum in Chicago, where a few were exhibited next to reproductions made to appear ancient (Kawami 2023:117). A portion went to the Iraq National Museum in Baghdad, and one example was sent to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford (K. 1436, fig. 7.6a, Kawami 2023:117).

Other finds in the palaces

Watelin and his team found many other objects in the palaces, including several incantation bowls (Moorey 1978: 122). These bowls had been inserted upside-down into the structure of the buildings, during construction. They are inscribed with incantations in three scripts: Aramaic, Syriac, and Mandaic in order to protect the inhabitants from evil spirits. Incantation bowls are well known in Iraq. They have been found on many sites, at Babylon, Nippur and Adab in the south for example, and at Assur in the north, usually in late Sassanian archaeological contexts, 6th-early 8th centuries AD (Moorey 1978: 122-4; Hunter 2021). Unfortunately the incantations bowls from Kish have not yet been published in a modern edition. A remarkable lead scroll was also discovered in palace 7, under the threshold of one of the rooms. It is also likely to have contained a protective inscription but it is rolled up so tightly that it cannot now be read. The scroll is today in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford (Ashmolean AN 1933.1285 [https://www.ashmolean.org/collections-online#/item/ash-object-464533]) (Moorey 1978: 141).

Many fragments of glass vessels, blue glazed pottery, and terracotta figurines were also discovered in these palaces (Pope 1935: 20). Tests on some of the glass fragments have shown that they were likely made with sand and soda plant ash (Dussubieux 2023: 52). In villa 7, a hoard of bronze coins, many too corroded to be legible, still survived. Despite their state, Langdon reported that "161" of them could be identified as Roman bronze coins from 4th and 5th centuries AD (Langdon and Harden 1934: 123; Moorey 1978: 141).

Who lived in the palaces?

Today, we are not able to identify exactly who lived in these palaces, but historian Trudy Kawami has argued that these homes may have been built by the Arabic-speaking Lakhmid elite, who ruled an independent kingdom centred on Hira, 70 km south of Kish in the late Sassanian and early Islamic periods. They probably built these palaces as lush retreats by the Euphrates, far from the city, where families and friends could escape the intense heat of the summer, with gardens and patios with pools.

Although the palaces have not yet been fully studied, they vastly enriched our knowledge of the history of the Sasanian period in Iraq and its material culture (Kawami 2023:124). The stuccos from Kish are unique in art history and like most discoveries from the site they show how important Kish is to the history of Iraq and of the region.

15 Sep 2025

Nadia Aït Saïd-Ghanem

Nadia Aït Saïd-Ghanem, 'Sassanian Villas or Palaces (Mounds G–H)', The Forgotten City of Kish • مدينة كيش المنسية, The Kish Project, 2025 [http://oracc.org/MoundsofKish/TellIngharra/SassanianVillas/]