The French mission, spring 1912

In late 1911, the Ottoman Government granted a two-year permit to excavate at Kish to Henri de Genouillac (1881–1940) PGP (Figure 1), hitherto a museum-based Assyriologist with no fieldwork experience but with official French funding and diplomatic backing (Chevalier 2002: 510). With 80–180 local labourers working for eight and a half hours a day, six days a week (Figure 2), he directed them to dig for tablets and other artefacts wherever looked most promising, ignoring or ignorant of the more systematic methods of excavation and documentation that a German-led team had been using for over a decade already at nearby Babylon. Starting around the ziggurat at Uhaimir, where local men had already been excavating unofficially, he also sent teams to tells further east, including Tell Bandar and Ingharra (Moorey 1978: 11–13).

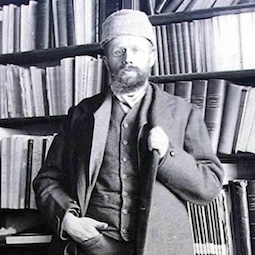

[/kish/images/genouillac-large.jpg]

[/kish/images/genouillac-large.jpg]Figure 1: Henri de Genouillac, August 1929 (unknown photographer). Source: Reddit [https://www.reddit.com/r/Assyriology/comments/mazdlv/old_photo_of_archaeologist_henri_de_genouillac/#lightbox]

The expedition erupted into controversy after just a few weeks, in February 1912, when his Ottoman official liaison, Bedry Bey PGP (Figure 3), who also worked with the Germans at Babylon, objected to Genouillac flying the French flag over his on-site tent (Genouillac 1924–25: I, 16). The dispute escalated into to a full-blown scandal when Genouillac, convinced that the Germans and Ottomans were conspiring against him, physically assaulted another government representative with his whip. Unsurprisingly, the mayor of Baghdad immediately withdrew the permit, and the French authorities did not support Genouillac's pleas to be re-instated (Chevalier 2002: 97–99). Even in January 1919, an official French review of likely archaeological sites in former Ottoman territories did not consider returning to Kish (Chevalier 2002: 234–235, 272 n162).

[/kish/images/kish-staff-1912-large.png]

[/kish/images/kish-staff-1912-large.png]Figure 2: The assembled field staff of Genouillac's Kish expedition, early 1912. Source: Genouillac, PRAK I, pl. I/1.

Genouillac's three-month treasure-hunt yielded some 1400 cuneiform tablets and 325 other artefacts, which he packed "in 11 cases" to be sent to the Imperial Ottoman Museum (IOM) in Istanbul (Genouillac 1924–25: I, 19–20; Charpin 2022: 7.17–18). In order to circumvent the excavation permit's express prohibition on exporting archaeological finds, he also purchased about 150 cuneiform tablets and 200 other objects for the Louvre. The antiquities dealer Alexander Messayeh PGP directly references Genouillac's attemps to escape the official requisition of objects in a letter dated 15 March 1912, two months after the start of the excavation, writing "I am well aware that you [Genouillac] can easily make almost anything good disappear without him realising and that you prefer doing this" [1]. The "him" was Abdul Settar, an Ottoman commissioner assigned to the mission. Genouillac also bought tablets for his own personal collection, like many other Western excavators of his time (Lecompte and Pariselle 2017: 106–107; Çelik 2016: 154).

[/kish/images/kish-excavation-1912-large.png]

[/kish/images/kish-excavation-1912-large.png]Figure 3: An excavated building at Kish, in early 1912. The man in the centre, wearing a fez, may be Bedry Bey or one of his colleagues in the Ottoman government of Iraq. Source: Genouillac, PRAK I, pl. XIII/1.

Although Genouillac was understandably cagy in print about the circumstances of these transactions, surviving letters reveal a great deal of information about his purchases and the circulation of Kish artefacts. In particular, these documents illustrate how, in addition to helping him secure Kish artefacts, antiquities dealers assited Genouillac with the management of his excavation. Messayeh's letter of 15 March 1912 for example indicates that he had taken charge of paying the mission's team members. Several men had family members in Baghdad who could come to collect their wages directly from Messayeh, presumably while they remained on site. This letter also preserves several names: for example, Petros Salman who was paid "2 pound sterlings", and "Saleh and his workmen" who received "2 pound sterlings" [2]. Thanks also to details Genouillac shared in his excavation report, we know that wages differed between job types and age categories, with 5 piasters to team leaders, 3 piasters to shovellers, while teenagers (13 to 15 year-olds) received 2.5 piasters (Genouillac 1924–25: I, 30).

In May 1922, very early in the planning process for the OFME, Stephen Langdon PGP offered Genouillac a position on the team as an Assyriologist. But the latter took offence that he was not being considered for field director, and the conversation soon petered out (Genouillac 1924–25: I, 29 n2).

De Genouillac's report was published in 1924, twelve years after the closure of the excavation. In April 1924, he had finally got access in the IOM to the eleven cases of finds he had packed over a decade earlier (Genouillac 1924–25: I, 19–20). The resulting two-volume publication comprised a short narrative account of the excavations, including fascinating details of its operation and grumpy asides about perfidious colleagues, architect Raoul Drouin's PGP plans of the ziggurat at Uhaimir, plus a catalogue and hurried line drawings of over a thousand of the most complete cuneiform tablets his workers had found (Genouillac 1924–25). De Genouillac also included a few pages of the diary he kept at Kish, which included the names of some of his team members, together with the finds they made, and on which day. For example, Petros who found a "religious image" on the morning of 3 February, while team leader Ali Schammeri and his crew found a tablet bearing the image of "a god with his hand extended to the left" on 7 February (Genouillac 1924–25: II, 34). It is to these individuals and many others unnamed to whom we owe the finds we admire and study today.

Notes

- Messayeh letter to Genouillac, 15 March 1912: "J'espère que vous avez déjà fini vos fouilles de Palais et que vous continuez dans des autres endroits, et que aurez réussi à trouvé de jolies choses, je sais bien que vous pouvez facilement faire disparaitre presque tout ce qui est bon et sans qu'il s'en perçoive et vous préferez cela". [Return to main text]

- Messayeh Letter to Genouillac, 15 March 1912: "D'après vos avis j'ai payé les sommes suivants (sic) 2 Ltg à la famille de Petros Salman [Genouillac's team leader] [...] 2 Ltg à Saleh et ses 2 ouvriers comme solde de leur avoir [...]". [Return to main text]

03 Jul 2025

Nadia Aït Saïd-Ghanem & Eleanor Robson

Nadia Aït Saïd-Ghanem & Eleanor Robson, 'The French mission, spring 1912', The Forgotten City of Kish • مدينة كيش المنسية, The Kish Project, 2025 [http://oracc.org/ModernhistoryofKish/Frenchmission1912/]