The king's advisors: magnates and scholars

As the ruler of Assyria and overlord of the entire Middle East, the king was responsible to no one but the gods. Yet while official inscriptions portray the king confidently making his decisions alone, guided only by the gods, the reality was different. In the 7th century BC, several members of the royal family, male and female, wielded considerable influence over the king but he was also advised by others: state officials with administrative and military functions on the one hand and scholars - experts in divination and ritual - on the other hand.

The king, human agent of the gods

The Assyrian king wearing a necklace with the symbols of divine power; detail from the stone decoration of Assurnasirpal II's Northwest Palace at Kalhu, c.865-860 BC (room B, panel 23; BM ANE 124531). Photo by Eleanor Robson. View large image.

As the chosen representative of the god Aššur PGP , the Assyrian king's power was absolute, restricted only by his being answerable to the gods and by the ideal that a good king must exercise a just rule. The expected conduct of a king is well described by a passage from Assurbanipal's so-called Coronation Hymn:

May eloquence, understanding, truth and justice be given to him (i.e. Assurbanipal) as a gift! May the people of Assyria buy thirty kor TT (c.9000 litres) of grain for one shekel TT (c.8.3 grams) of silver! May the people of Assyria buy three seah (c.30 litres) of oil for one shekel of silver! May the people of Assyria buy thirty minas TT (c.15 kilograms) of wool for one shekel of silver! May the lesser speak, and the greater listen! May the greater speak, and the lesser listen! May concord and peace be established in Assyria! Aššur is king - indeed Aššur is king! Assurbanipal is the [representative] of Assur, the creation of his hand.

The king personally selected and appointed every official, including temple functionaries ("priests"). Sometimes at least, but quite possibly routinely, he asked the gods to guide his decisions: the later chief eunuch TT Nabu-šarru-uṣur PGP was only chosen for this office by Assurbanipal after a divinatory query to the sungod Šamaš PGP gave a favourable result (SAA 4: 299).

The "great ones" of Assyria

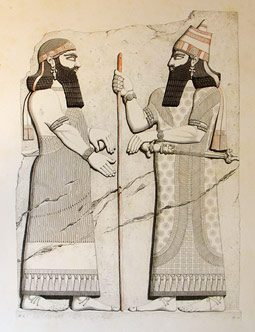

King Sargon conferring with a magnate; drawing of the stone decoration of Sargon's palace in Khorsabad (facade L, slab 12); from P.E. Botta and E. Flandin, Monument de Ninive I (Paris 1849) pl. 12. View large image.

The chief eunuch was one of a group of top officials, called the "the great ones", that held the highest officially recognized authority in Assyria, apart from the king and selected members of the royal family. As the literary meaning of some of their titles illustrates, these magnates were historically the highest members of the palace staff. The nagir ekalli ("palace herald"), the rab šaqe (the "chief cup-bearer"), the turtanu (the "commander-in-chief" - a loanword from Hurrian literally meaning "second one"; the highest general after the king himself) and the masennu (a loanword from a Hurrian term of unknown meaning) all commanded their own provinces and therefore spent a considerable amount of time away from the king's presence. The rab ša reši ("chief eunuch"), the sukkallu (a loanword from Sumerian describing the second-highest state official after the king) and the sartinnu (a loanword from a Hurrian term of unknown meaning), on the other hand, did not control provinces but can often be seen travelling on behalf of the king all over the empire and beyond. These officials were among the king's closest advisors and may even have formed a kind of state cabinet. While it is clear that they did not permanently stay at the royal court or in the king's proximity, yearly religious festivals, such as the New Year TT celebration at Assur PGP , would have provided fixed opportunities to meet on a regular basis. At these occasions also, the provincial governors were required to join the king and had the chance to meet with him in person. But these encounters were shaped by heavy protocol, and an audience with the king was always a strictly regulated privilege, especially in the 7th century after the murder of Sennacherib PGP and the failed conspiracy against Esarhaddon which had enjoyed the support of the Assyrian "great ones".

Nevertheless, magnates and governors as well as other high-ranking administrative and military officials undoubtedly played a significant role in the royal decision-making process and counselled their ruler on a variety of issues, in person or in writing. For example, Mar-Issar PGP , Esarhaddon's political agent in Babylonia, advised the king in his letters on matters as diverse as the restoration of Babylonian temple cults (SAA 10: 359), the choice of a suitable candidate for the Substitute King Ritual (SAA 10: 352), and the punishment of a corrupt governor who embezzled temple funds (SAA 10: 369). But while these trusted officials' recommendations may have carried great weight the most important advisors of the king were the gods.

Interpreters of divine messages

Scholars making a sacrifice in front of the royal chariot on a military campaing; detail from the stone decoration of Sennacherib's Southwest Palace at Nineveh, c.720 BC (room XXXVI, panels 14-16, BM ANE 12491306). Photo by Eleanor Robson. View large image.

Assyrians lived in a world that was full of the gods' messages to man; the gods spoke incessantly, through the movement of the stars, through the lie of the land, through the flight of the birds, through everything. To know what the gods wanted was useful for anyone, but for the Assyrian king it was imperative to rule in accordance with divine will. Therefore, the king employed consultants that looked out for the gods' communications and interpreted them for his benefit; they were "keeping the king's watch" (e.g. SAA 10: 143, 173, 334). Divination experts were active in temples all over the empire and were required to pass on relevant data immediately, be it gained through routinely pursuing astrology and extispicy or be it chance information like abnormal births TT (SAA 10: 120) or earthquakes TT (SAA 10: 55, 56). But there was an inner circle of top-notch specialists to whom the king turned as matter of course in order to understand the gods' plans and wishes.

These men's background was quite distinct from those officials that held administrative and military power in the Assyrian empire. While the king employed able scholars regardless of their origin and even experts from Elam PGP and Egypt PGP (best illustrated by SAA 10, 160), the members of the inner circle all belonged to certain ancient Assyrian and sometimes Babylonian families whose members had devoted themselves to scholarship for generations. They were therefore often related to one another; brothers, fathers and sons, uncles and nephews can be seen working together in the king's service, and family connections were as important as scholarly expertise when it came to gaining a place in the king's inner circle. Esarhaddon's chief scribe Nabu-zeru-lešir PGP , an astrologer TT , and his chief exorcist TT Adad-šumu-uṣur PGP were brothers and members of the most prominent Assyrian scribal family, and their sons were in royal service as well, while several relatives of Bel-upahhir PGP , a Babylonian astrologer and the "chief scholar" (ummānu) of king Sennacherib PGP , continued the family tradition in the employ of Esarhaddon.

The king and his "chief scholar"

Each Assyrian king had one "chief scholar" at his side, and their relationship was thought to mirror that of the first kings of Mesopotamia, who ruled before the Great Flood, and the immortal fish-creatures (apkallu) who had been sent by the gods to counsel and teach them. Balasi, who held the post of "chief scholar" during Assurbanipal's reign, had been his tutor before he became king. He clearly had a very close and personal bond with Assurbanipal but also with his father, as is best illustrated by the almost impertinent but also clearly concerned letter in which he urges Esarhaddon to stop his unhealthy fasting (SAA 10: 43).

The power of the king's scholars

While the scholars' influence derived from their ability to explain divine will to the king, and execute on his behalf, it is obvious that their access to the king was far less restricted than that of the magnates and governors, and their impact in royal decision making can therefore hardly be overemphasized. Their letters indicate that they expected the king to listen to them, and not just when they reported the gods' messages. They often ask for personal favours such as gifts (e.g. SAA 10: 294), royal backing in private conflicts (e.g. SAA 10: 165, 167) or the advancement of their protégés (e.g. SAA 10: 118). Matters such as these certainly had considerable impact on different levels of inner-Assyrian affairs but the scholars' advice also directly affected the foreign policy of the Assyrian empire. Taking his departure from interpreting a meteor TT sighting as predicting the destruction of an enemy army the astrologer Bel-ušezib PGP gives extremely specific advice on how to invade Mannea PGP , a kingdom east of Assyria:

If the king has written to his army: 'Invade Mannea,' the whole army should not invade; (only) the cavalry and the professional troops should invade. The Cimmerians PGP who said, 'The Manneans are at your disposal, we shall keep aloof' - maybe it was a lie; they are barbarians who recognize no oath sworn by god and no treaty. [The cha]riots and wagons should stay side by side [in] the pass, while the [ca]valry and the professionals should invade and plunder the countryside of Mannea and come back and take up position [in] the pass. [If], after they have repeatedly entered and plundered the open country, the Cimmerians have not advanced against them, the [whole] army can enter and [throw itself] against the cities of Mannea. ... I am writing to the king, my lord, without knowing the exit and entry of that country. The lord of kings should ask an expert of the country, and the king should (then) write to his army as he deems best. Deserters outnumber fighting men among the enemy - therein lies your advantage. At the entry of the whole army, let patrols make sorties, capture their men in the open country and question them. ... The king may happily do as he deems best. (SAA 10: 111)

This is not the counsel of a bookworm who knows nothing of the world of war. While acknowledging that he is unfamiliar with Mannean geography Bel-ušezib gives detailed strategic advice that cannot readily be linked with the brief forecast gained from the meteor shower but seems rather like his personal opinion on how to stage the invasion. Yet coming from the distinguished scholar who, in the chaos following Sennacherib's murder, had predicted Esarhaddon's rule and been one of his earliest supporters (SAA 10: 109), the king will have considered the astrologer's views carefully. Today, it is difficult to judge whether the great influence of the scholars in the royal entourage was a new development of the reign of Esarhaddon, at the expense of the magnates and generals whose power was curbed after the conspiracies against Sennacherib and Esarhaddon himself, or whether the scholars' opinions had already held equal weight to that of the members of the administrative and military establishment earlier in Assyrian history. In the 7th century, however, men like the astrologer Bel-ušezib played a very real role in shaping the king's decisions, as interpreters of the gods and in their own right.

Further reading

- Fales and Lanfranchi, 'The impact of oracular materials', 1997

- Leichty, 'Divination, magic, and astrology', 1997

- Mattila, The king's magnates, 2000

- Péçirková, 'Divination and politics', 1985

Content last modified: 27 Mar 2024.

Karen Radner

Karen Radner, 'The king's advisors: magnates and scholars', Knowledge and Power, Higher Education Academy, 2024 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/saao/knpp/essentials/kingsadvisors/]