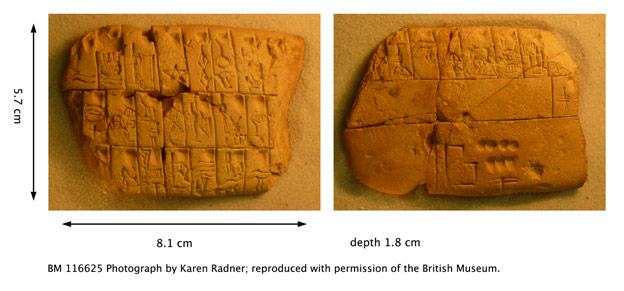

BM 116625: proto-cuneiform lexical list from Jemdet Nasr

BM 116625: proto-cuneiform lexical text ('Geographical' List) from Jemdet Nasr (Uruk III period, c. 3000 BC). Photograph by Karen Radner; reproduced with permission of the British Museum. View large image.

While the earliest known texts are predominantly administrative in nature (like BM 116628), a significant minority belong to an altogether different category — lists of signs. There are lists for such categories as plants, animals, and officials. Each ruled box on the tablet contains one entry, introduced by a single rounded impression. Such lists are found already among the earliest texts from Uruk PGP in the late fourth millennium BC. By the Uruk III period (c.3000 BC) they constitute almost 20% of all known documents. The order in which the entries occur in each list became standardised, and copies of them continued to be made for centuries to come. Several lists are even known from Ur III and Old Babylonian copies (c.2100-1600 BC), well over 1000 years after they were first composed. The most common list, both in archaic Uruk and in later copies, was a catalogue of officials' titles.

The incredible longevity of these lists provides us with an invaluable aid for reading the early documents. For the easily recognisable signs of the later copies allow us to identify their much more difficult ancestral forms. Lexical lists are one of the defining characteristics of cuneiform culture. Every trained scribe would have grown up memorising their contents. Such lists are still present among the last clay tablets to be written, 3000 years later.

Why, then, were the lists first created? The old theory that the lists set out to record and put in order everything in existence is increasingly rejected. Disparities between the sign repertoire of lists and that of contemporary administrative texts have inspired the idea that the lists are evidence of the early scribes experimenting with their new technology, testing the limits of what was possible. In a system where signs were images of things, and with a repertoire of between 1000–2000 characters, a more pragmatic solution suggests itself. The lists could originally have served to provide models of sign forms and teach the rules of their relationships to each other, especially in the case of those signs that were derived from others.

For more online photos, view the record for this tablet on the British Museum's research database [http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/search_the_collection_database.aspx].

A transliteration of the text can be found in Englund & Grégoire, MSVO 1 (1991), no. 243.

Content last modified on 10 Jan 2017.

Jon Taylor

Jon Taylor, 'BM 116625: proto-cuneiform lexical list from Jemdet Nasr', Knowledge and Power, Higher Education Academy, 2017 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/saao/knpp/cuneiformrevealed/tabletgallery/bm116625/]