Sîn-šarra-iškun's Wars with Nabopolassar

Two Babylonian Chronicles — the so-called "Chronicle Concerning the Early Years of Nabopolassar" and "Fall of Nineveh Chronicle" (see below for translations) — provide the backbone for the long war between Sîn-šarra-iškun and Nabopolassar.[230] These two chronographic documents, together with the dates of Babylonian economic documents,[231] chart the two rulers' fight for control over Babylonia between 626 and 620[232] and then the Babylonian and Median invasion of the Assyrian heartland and annihilation of its cities and cult centers between 616 and 612.

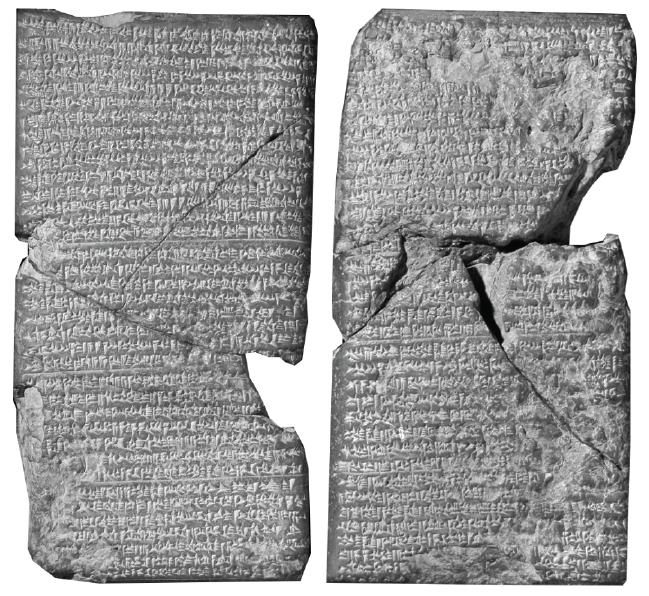

Obverse and reverse of the "Fall of Nineveh Chronicle" (BM 21901). © Trustees of the British Museum.

Up until 615, his 12th year as king, Sîn-šarra-iškun, with the assistance of allied troops from Egypt, was able to keep Nabopolassar at bay, mostly because the battles fought between the two rulers took place in northern Babylonia or in the Middle Euphrates region, and not on Assyrian soil. Everything, however, changed in 615, when Cyaxares (Umakištar), "the king of the Umman-manda" (Medes), joined the fight. In that turn-of-events year, Nabopolassar invaded the Assyrian heartland and attacked Aššur. He failed to capture that important religious center and was forced to retreat south, as far as the city Takritain (modern Tikrit). In the following year, 614, Cyaxares marched straight into the heart of Assyria and roamed effortlessly through it, first capturing Tarbiṣu, a city in very close proximity to Nineveh, and then Aššur, which the Babylonians had failed to take in 615.[233] Upon hearing this news, Nabopolassar quickly marched north and forged an alliance with the Median king. The unexpected union not only gave fresh impetus to Nabopolassar's years-long war with Sîn-šarra-iškun, but also removed any hopes that the Assyrian king might have had about the survival of his kingdom. Sîn-šarra-iškun could clearly see the writing on the wall and he took what measures he could to fortify Nineveh.[234] In 613 (if not earlier, in 614 or 615), that city's gates were reinforced by narrowing them with massive blocks of stone. The death blow for Sîn-šarra-iškun and his capital came during the following year, in 612. Nineveh's fortifications, even with the improvements made to its defenses, were not sufficient to prevent a joint Babylonian-Median assault from breaching the city's walls. After a three-month siege — from the month Simānu (III) to the month Abu (V) — Nineveh fell and was looted and destroyed.[235] Before the city succumbed to the enemy,[236] Sîn-šarra-iškun died. Unfortunately, the true nature of his death — whether he committed suicide, was murdered by one or more of his officials, or was executed by the troops of Nabopolassar or Cyaxares — is not recorded in cuneiform sources, including the Fall of Nineveh Chronicle (see below).[237]

Notes

[230] The former chronographic text, as far as it is preserved, records events from 627 (Sîn-šarra-iškun's accession year) to 623 (Sîn-šarra-iškun Year 4 = Nabopolassar Year 3), but it would have included descriptions of the clashes between Assyria and Babylonia up to the year 617 (Sîn-šarra-iškun Year 10 = Nabopolassar Year 9). Based on information presented in the latter chronicle, which records the events of 616 (Sîn-šarra-iškun Year 11 = Nabopolassar Year 10) to 609 (Aššur-uballiṭ Year 3 = Nabopolassar Year 17), the accounts for the years 622–617 would likely have narrated how Nabopolassar and his army expelled the Assyrians from Babylonia, which they were able to do in 620 (Sîn-šarra-iškun Year 7 = Nabopolassar Year 6), at least based on the date formulae of business documents.

[231] For a catalogue of the economic texts dated by his reign, see Brinkman and Kennedy, JCS 35 (1983) pp. 54–59. Those business documents, the earliest of which date to his accession year and the latest to his 7th year as king, come from Babylon (Accession Year), Kār-Aššur (Year 7), Maši... (year damaged), Nippur (Years 2–6), Sippar (Accession Year, Years 2–3), and Uruk (Years 5–7).

[232] The two men vied for control over Babylon, Nippur, Sippar, and Uruk. It is clear that Uruk changed hands on more than one occasion; see Beaulieu, Bagh. Mitt. 28 (1997) pp. 367–394. The latest economic document dated to Sîn-šarra-iškun's reign from Babylonia comes from Uruk and is dated to 12-X-620 (Brinkman and Kennedy, JCS 35 [1983] p. 58 no. O.45). This may well mark the end of Assyria's presence in Babylonia.

[233] On the last days of the city Aššur, see Miglus, ISIMU 3 (2000) pp. 85–99; and Miglus, Befund und Historierung pp. 9–11. There is evidence of burning throughout the city. The Assyrian kings' tombs, which were located in the Old Palace, were looted, their sarcophagi smashed, and their bones scattered and (probably) destroyed; see Ass ph 6785 (MacGinnis in Brereton, I am Ashurbanipal p. 284 fig. 292), which shows the smashed remains of an Assyrian royal tomb. It has been suggested that this destruction might have been the work of Elamite troops, who were paying Assyria back for Ashurbanipal's desecration of Elamite royal tombs in Susa in 646, which is described as follows: "I destroyed (and) demolished the tombs of their earlier and later kings, (men) who had not revered (the god) Aššur and the goddess Ištar, my lords, (and) who had disturbed the kings, my ancestors; I exposed (them) to the sun. I took their bones to Assyria. I prevented their ghosts from sleeping (and) deprived them of funerary libations" (Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 250 Asb. 11 [Prism A] vi 70–76).

Kalḫu was also destroyed in 614 and again in 612. See D. Oates and J. Oates, Nimrud passim; and Miglus, Befund und Historierung pp. 8–9. A well in Ashurnasirpal II's palace (Northwest Palace) filled with the remains of over one hundred people attests to the city's violent end (D. Oates and J. Oates, Nimrud pp. 100–104). Some of the remains might have been removed from (royal) tombs desecrated during Kalḫu's sack, while other bodies were thrown down there alive, as suggested from the fact that the excavators found skeletons with shackles still on their hands and feet. While Nabû's temple Ezida was being looted and destroyed, the copies of Esarhaddon's Succession Treaty (Parpola and Watanabe, SAA 2 pp. XXIX–XXXI and 28–58 no. 6) that had been stored (and displayed) in that holy building were smashed to pieces on the floor. For evidence of the selective mutilation of bas reliefs in the Northwest Palace, see Porter, Studies Parpola pp. 201–220, esp. pp. 210–218. For an overview of the widespread destruction of Assyria's cities, see MacGinnis in Brereton, I am Ashurbanipal pp. 280–283.

[234] As J. MacGinnis (in Brereton, I am Ashurbanipal p. 280) has pointed out, "the very size of the city [Nineveh] proved to be its fatal weakness. The length of its wall — a circuit of almost 12 kilometres — made it impossible to defend effectively at all places." The fact that Nineveh had eighteen gates, plus the Tigris River nearby, did not help.

[235] For evidence of Nineveh's destruction, which included the deliberate mutilation of individuals depicted on sculpted slabs adorning the walls of Sennacherib's South-West Palace and Ashurbanipal's North Palace, see, for example, Reade, AMI NF 9 (1976) p. 105; Reade, Assyrian Sculpture p. 51 fig. 73; Curtis and Reade, Art and Empire pp. 72–77 (with figs. 20–22), 86–87 (with figs. 28–29), and 122–123; Stronach in Parpola and Whiting, Assyria 1995 pp. 307–324 (with references to earlier studies); Reade, RLA 9/5–6 (2000) pp. 415–416 §14.3 and pp. 427–428 §18; Porter, Studies Parpola pp. 203–207; Reade, in Brereton, I am Ashurbanipal pp. 32–33 (with fig. 28); and Macginnis in Brereton, I am Ashurbanipal p. 281. One of the more striking examples of the selected mutilation by Assyria's enemies is the wide gash across Sennacherib's face in the so-called "Lachish Reliefs" (BM 124911) in Room XXXVI of the South-West Palace (Reade, Assyrian Sculpture p. 51 fig. 73). There is evidence of heavy burning in the palaces. The intensity of Nineveh's last stand is evidenced by excavation of the Halzi Gate, where excavators discovered the remains of people (including a baby) who had been cut down by a barrage of arrows as they tried to flee Nineveh while parts of the city were on fire. See Stronach in Parpola and Whiting, Assyria 1995 p. 319 pls. IIIa–b.

[236] Some (fictional) correspondence between Sîn-šarra-iškun and Nabopolassar from the final days of the Assyrian Empire exists in the form of the so-called "Declaring War" and "Letter of Sîn-šarra-iškun" texts. The former (BM 55467; Gerardi, AfO 33 [1986] pp. 30–38), which is known from a tablet dating to the Achaemenid or Seleucid Period, was allegedly written by Nabopolassar to an unnamed Assyrian king (certainly Sîn-šarra-iškun) accusing him of various atrocities and declaring war on the Assyrian, stating: "[On account] of the crimes against the land Akkad that you have committed, the god Marduk, the great lord, [and the great gods] shall call [you] to account [...] I shall destroy you [...]" (rev. 10–14). The (fictional) response is a fragmentary letter (MMA 86.11.370a + MMA 86.11.370c +MMA 86.11.383c–e; Lambert, CTMMA 2 pp. 203–210 no. 44), known from a Seleucid Period copy, purported to have been written by Sîn-šarra-iškun to Nabopolassar while the Assyrian capital Nineveh was under siege, pleading to the Babylonian king, whom the besieged Assyrian humbly refers to as "my lord," to be allowed to remain in power. For further details about these texts, see, for example, Lambert, CTMMA 2 pp. 203–210 no. 44; Frahm, NABU 2005/2 pp. 43–46 no. 43; Da Riva, JNES 76 (2017) pp. 80–81; and Frazer, Akkadian Royal Letters.

[237] See the section Ashurbanipal's Death above, esp. n. 178, for more information.

Jamie Novotny

Jamie Novotny, 'Sîn-šarra-iškun's Wars with Nabopolassar', RINAP 5: The Royal Inscriptions of Ashurbanipal, Aššur-etel-ilāni, and Sîn-šarra-iškun, The RINAP/RINAP 5 Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, 2023 [http://oracc.org/rinap/rinap5/rinap53introduction/sinsharraishkunashuruballitii/warswithnabopolassar/]