Sîn-šarra-iškun's Building Activities

Extant inscriptions record that Sîn-šarra-iškun undertook construction in the three most important cities of the heartland: Aššur, Kalḫu, and Nineveh.[218] Most of the work was very likely carried out before 615, at which point Assyria was fighting for its very existence.[219]

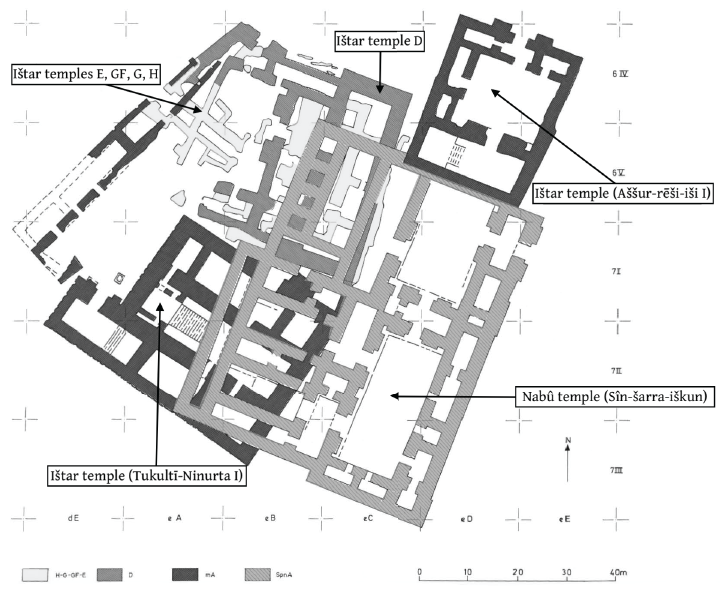

Plan of the Nabû temple at Aššur and the earlier ruins of the Ištar temple. Adapted from Bär, Ischtar-Tempel p. 391 fig. 5.

In the religious capital Aššur, he built a new temple for the god Nabû, since that god's place of worship was then inside Eme-Inanna ("House of the Mes of Inanna"), the temple of the Assyrian Ištar.[220] Sîn-šarra-iškun had Egidrukalamasumu ("House Which Bestows the Scepter of the Land") constructed on a vacant plot of land, which concealed the ruins of earlier, long-abandoned Ištar temples.[221] Nabû's new earthly abode took several years to complete[222] and, once it was finished, the statues of the god of scribes and his wife Tašmētu were ushered into the temple during a grand ceremony; at that time, prize bulls and fat-tailed sheep were presented as offerings. Although Sîn-šarra-iškun claims to have made the new temple "shine like daylight," no details about its sumptuous decoration are recorded in extant texts. We do know, however, that he presented (inscribed) reddish gold kallu-and šulpu-bowls to Nabû, a silver spoon (itqūru) to Tašmētu, and musukkannu-wood offering tables (paššuru) to the goddesses Antu and Šala.[223]

At Kalḫu, Sîn-šarra-iškun completed his brother Aššur-etel-ilāni's work on Ezida ("True House"), Nabû's temple in that city, since construction on that sacred building remained unfinished when Sîn-šarra-iškun became king.[224]

At his capital, Nineveh, he made repairs to the mud-brick structure of the city wall Badnigalbilukurašušu ("Wall Whose Brilliance Overwhelms Enemies"), renovated the western part of the South-West Palace (Egalzagdinutukua ["Palace Without a Rival"] = Sennacherib's palace), and, probably, sponsored a few other projects in that metropolis.[225] As for work on the "Alabaster House" (=the South-West Palace), which served as an administrative center,[226] Sîn-šarra-iškun's renovations might have included (1) partially redecorating Room XXII with scenes of the landscape around Nineveh and a triumphal procession of men wearing foliage on their heads; (2) recarving the walls of Court XIX and Room XXVIII with scenes of warfare; and (3) removing the former images of the wall panels in Room XLII and Court XLIX so that they could be resculpted with new images.[227] Presumably in 613 (if not earlier), he strengthened the vulnerable spots in Nineveh's defenses, principally by reinforcing its eighteen gates and narrowing their central corridors with large blocks of stone;[228] Sîn-šarra-iškun was able to do this since his rival Nabopolassar was preoccupied with a rebellion in Sūḫu, a kingdom situated in the Middle Euphrates region. [229]

Notes

[218] For See also Novotny and Van Buylaere, Studies Oded pp. 215–219. It is unlikely that Sîn-šarra-iškun rebuilt Ešaḫula, the temple of the god Nergal in Sirara, the temple district of Mê-Turān, since the text recording that work (Stephens, YOS 9 no. 80) was probably written in the name of Ninurta-tukultī-Aššur, and not that of Sîn-šarra-iškun; see the section Texts Excluded from RINAP 5/3 above.

[219] For See the section Eponym Dates below for discussions of the dates of Sîn-šarra-iškun's inscriptions (and associated building projects).

[220] For Ssi 7–14. For Egidrukalamasumu, see, for example, George, House Most High p. 94 no. 397; Novotny and Van Buylaere, Studies Oded pp. 216–218; Schmitt, Ischtar-Tempel pp. 82–100; Novotny, Kaskal 11 (2014) pp. 159–169; and Novotny in Yamada, SAAS 28 pp. 262–263. For Eme-Inanna, see, for example, George, House Most High pp. 122–123 no. 756; and Schmitt, Ischtar-Tempel pp. 26–81.

[221] The western part of the temple was constructed directly above Ištar Temples H, G, GF, E, and D, and the Ištar temple that had been built by Tukultī-Ninurta I. Its northern wall abutted the southern wall of the still-in-use Ištar temple that had been originally constructed by Aššur-rēšī-iši I. See Novotny, Kaskal 11 (2014) p. 163 fig. 1. Sîn-šarra-iškun's scribes, at least according to the building account of the so-called "Cylinder A Inscription" (for example, Ssi 10 lines 22b–27a), regarded the ruins to be the remains of earlier Nabû temples constructed by the Middle Assyrian kings Shalmaneser I (1273–1244) and Aššur-rēšī-iši I (1132–1115) and the Neo-Assyrian ruler Adad-nārārī III (810–783). That same inscription (line 29) claims that the temple was erected "according to its original plan, on its former site," which was not the case, because the new Nabû temple was constructed over the ruins of previous Ištar temples. Ssi 12 (lines 8–14a), a text engraved on a stone block, however, correctly states that the temple was built on an empty lot. For a brief study on the discrepancy between the textual and archaeological records, see Novotny, Kaskal 11 (2014) pp. 162–165. Note that the general ground plan of the Nabû temple at Aššur is very similar to that of the Ezida temple at Kalḫu. Compare fig. 4 with D. Oates and J. Oates, Nimrud p. 112 fig. 67.

[222] According to the dates of Sîn-šarra-iškun's inscription, construction on this sacred building took at least three years to complete. See the section Eponym Dates below for further information.

[223] Ssi 15–18.

[224] Ssi 19 (lines 30–37). For bibliographical references to Ezida, see n. 205 above.

[225] Ssi 1–6. The building report of Ssi 1 (lines 12´–15´) records work on the Alabaster House and that of Ssi 6, at least according to its subscript (rev. 13´), would have described construction on Nineveh's city wall. The building accounts of other inscriptions of his from Nineveh (Ssi 2–5) are either completely missing or not sufficiently preserved to be able to determine what accomplishment of Sîn-šarra-iškun they commemorated. For information on Sennacherib's palace, see, for example, Reade, RLA 9/5–6 (2000) pp. 411–416 §§14.2–3; Grayson and Novotny, RINAP 3/1 p. 17; and Jeffers and Novotny, RINAP 5/2 p. 15. For a detailed and comprehensive study of the "Palace Without a Rival" (=the South-West Palace), see J.M. Russell, Senn.'s Palace. For information on the palace reliefs, see Barnett et al., Sculptures from the Southwest Palace; Lippolis, Sennacherib Wall Reliefs; and J.M. Russell, Final Sack. For studies on Nineveh's wall, see Reade, RLA 9/5–6 (2000) pp. 397–403 §§11.1–4; Grayson and Novotny, RINAP 3/1 pp. 17–19; and Reade, SAAB 22 (2016) pp. 39–93.

[226] For details, see Reade, RLA 9/5–6 (2000) p. 415 §14.3.

[227] Some of these changes might have taken place already during the reign of his father Ashurbanipal, as stated already in Jeffers and Novotny, RINAP 5/2 (p. 15).

[228] For the evidence from the Adad, Halzi, and Šamaš Gates, see Stronach in Parpola and Whiting, Assyria 1995 pp. 307–324; and Pickworth, Iraq 67 (2005) pp. 295–316. Sîn-šarra-iškun might have also strengthened the western part of the South-West Palace since it could be accessed from the Step Gate of the Palace and the Step Gate of the Gardens.

[229] Fall of Nineveh Chronicle lines 31–37; see the Chronicles section below for a translation of that passage.

Jamie Novotny

Jamie Novotny, 'Sîn-šarra-iškun's Building Activities', RINAP 5: The Royal Inscriptions of Ashurbanipal, Aššur-etel-ilāni, and Sîn-šarra-iškun, The RINAP/RINAP 5 Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, 2023 [http://oracc.org/rinap/rinap5/rinap53introduction/sinsharraishkunashuruballitii/sinsharraishkunsbuildingactivities/]