Babylon

In 689, Sennacherib captured, looted, and destroyed Babylon,[91] as he described in his so-called "Bavian Inscription":

Although the actual destruction was probably not as bad as described in royal inscriptions, Babylon, with the god Marduk's temple Esagil ("House Whose Head Is High") at its heart, ceased to be the bond that linked heaven and earth. That connection was severed when Esagil, the most sacred building in the city's Eridu district, had been destroyed and when Marduk's statue and its paraphernalia (including an ornately-decorated bed) had been carried off to Assyria and placed in Ešarra ("House of the Universe"), the temple of the Assyrian national god Aššur, located in the Baltil quarter of Aššur.[93]

Soon after becoming king in late 681, in the wake of Sennacherib's murder,[94] probably during his 2nd regnal year (679), Esarhaddon, Ashurbanipal's and Šamaš-šuma-ukīn's father, initiated construction in Babylon so that that important Babylonian city would once again be a bond between heaven and earth.[95] From that time onwards, until his death on 10-VIII-669, Esarhaddon made a concerted effort to restore Babylon, its city walls Imgur-Enlil ("The God Enlil Has Shown Favor") and Nēmetti-Enlil ("Bulwark of the God Enlil"), and its temples, especially its most sacred buildings Esagil and Etemenanki ("House, Foundation Platform of Heaven and Netherworld").[96] This Assyrian king described the rebuilding of Babylon's most important structures as follows:

From sometime after 28/29-III-679 until 10-VIII-669, Esarhaddon rebuilt Imgur-Enlil, Nēmetti-Enlil, Esagil, Etemenanki, the processional way, and Eniggidrukalamasuma ("House Which Bestows the Scepter of the Land"), the temple of the god Nabû of the ḫarû.[100] To promote urban renewal, the Assyrian king, as the de facto ruler of Babylon, strongly encouraged Babylon's citizens to resettle the city, build houses, plant orchards, and dig canals.[101] At home, in an appropriate workshop in the religious capital Aššur, in the Aššur temple Ešarra, Esarhaddon had skilled craftsmen restore the divine statues of Marduk and his entourage (Bēltīya [Zarpanītu], Bēlet-Bābili [Ištar], Ea, and Mandānu) and had several cult objects fashioned.[102] Despite Esarhaddon's best efforts, and contrary to what his inscriptions record, work on Esagil (and Etemenanki) remained unfinished and the refurbished statue of Marduk remained in Assyria when he died in late 669.[103] The completion of that work fell to Ashurbanipal and Šamaš-šuma-ukīn, whom Esarhaddon had officially designated to replace him in II-672.[104]

Shortly after his official coronation as king of Assyria in I-668, in the month Ayyāru (II), Ashurbanipal traveled south to Babylon with his older brother Šamaš-šuma-ukīn, the statues of Marduk and his entourage, and numerous priests and temple personnel.[105] The Assyrian king describes the trip from Baltil (Aššur) to Šuanna (Babylon) as follows:

Marduk, Bēltīya (Zarpanītu), Bēlet-Bābili (Ištar), Ea, and Mandānu were returned to their temples and Šamaš-šuma-ukīn was placed on the throne, just as Esarhaddon had intended to do while he was still alive.[107]

As work in Babylon was still incomplete in II-668, Ashurbanipal — despite the fact that Šamaš-šuma-ukīn was the king of Babylon, although not yet officially since he still had to take the hand of Marduk during an akītu-festival — took it upon himself to finish what his father had started.[108] First and foremost was the completion of Babylon's two most important structures: Marduk's temple and ziggurat Esagil and Etemenanki, together with their shrines, platforms, and daises. [109] As for Esagil, Ashurbanipal finished its structure;[110] adorned its interior, especially Eumuša ("House of Command"),[111] Marduk's cella, which he "made glisten like the stars (lit. 'writing') of the firmament"; roofed it with beams of cedar (erēnu) and cypress (šurmēnu) imported from Mount Amanus and Mount Lebanon in the Levant;[112] hung doors of boxwood (taskarinnu), musukkannu-wood,[113] juniper (burāšu), and cedar in its (principal) gateways; and donated metal, wooden, and stone vessels for the cult. With regard to Etemenanki, he had its massive brick structure completed. In addition, Ashurbanipal claims to have built anew Ekarzagina ("House, Quay of Lapis Lazuli" or "House, Pure Quay"), the temple of the god Ea); Eturkalama ("House, Cattle-Pen of the Land"), the temple of Ištar of Babylon (Bēlet-Bābili), and Emaḫ ("Exalted House"), the temple of the goddess Ninmaḫ.[114] The arduous task of finishing the construction of Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil, the (inner) wall (dūru) and outer wall (šalḫû), was also accomplished;[115] this included hanging new doors in the (eight) city gates.[116]

At various times between 668 and 652, Ashurbanipal made significant donations to Marduk in Esagil. After the Egyptian metropolis Thebes was captured and plundered (ca. 664), the Assyrian army brought an abundance of gold, silver, and zaḫalû-metal back to the Assyrian capital Nineveh.[117] Two obelisks that were reported to have been "cast with shiny zaḫalû-metal" and to have weighed 2,500 talents (biltu) each, provided Ashurbanipal with a massive amount of metal for making the temples of his patron deities shine like daylight.[118] Esagil was one of the beneficiaries of Assyria's successes in Egypt. Ashurbanipal created an entirely new throne-dais (paramāḫu) for Marduk, one more resplendent than Aššur's Dais of Destinies in Ešarra at Aššur.[119] This new seat, which might have gone by the name "Tiʾāmat,"[120] was constructed from bricks cast from 50 talents (1,500 kg/3307 lbs) of zaḫalû-metal.[121] Around the same time, or in conjunction with the creation of the cast-brick throne-dais, Ashurbanipal had his craftsmen build a canopy (ermi Anu) from musukkannu-wood and clad with thirty-four talents and twenty minas (1020.8 kg/2250 lbs) of reddish gold. That covering was stretched out over Marduk's statue, which sat atop the throne-dais.

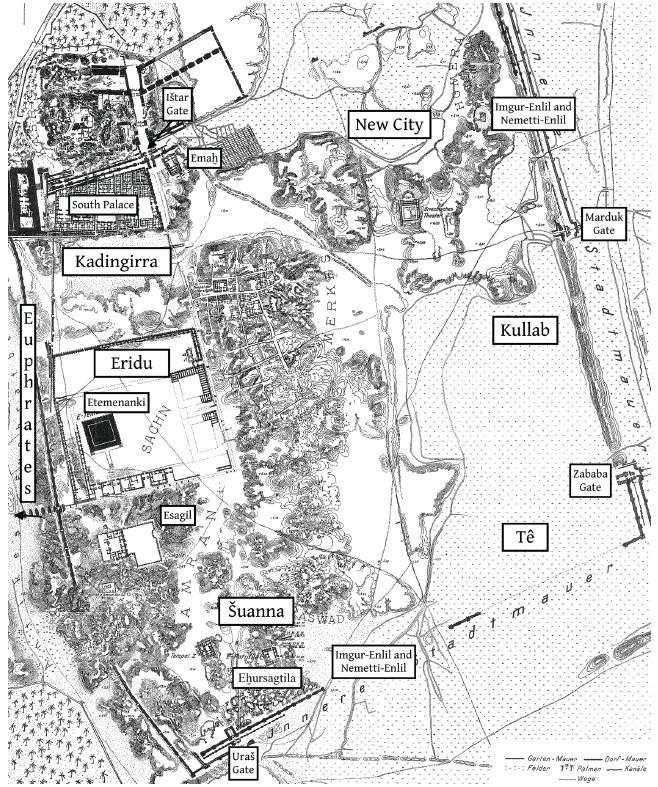

Annotated plan of the ruins of the eastern half of the inner city of Babylon. Adapted from Koldewey, WEB5 fig. 256.

In 656, or at the very beginning of 655 at the latest, Ashurbanipal was made aware of the fact that several objects of Marduk and his wife Zarpanītu that had been taken to Assyria by his grandfather Sennacherib in 689 in the wake of the destruction and plundering of Babylon and Esagil were still in the Aššur temple at Aššur. Sennacherib had given Babylon's tutelary deity's bed (eršu) and throne (kussû) to the Assyrian national god as part of his religious reforms that made the Aššur cult more like that of Marduk's at Babylon.[122] Before dedicating those objects to Aššur, Sennacherib had his scribes place inscriptions written in his name on them.[123] When Ashurbanipal learned of this appropriation of cultic objects, he reclaimed the bed and throne for Marduk. First, he had his scribes make copies of his grandfather's inscription(s) and record detailed descriptions of the objects.[124] Next, he had the metal-plating with Sennacherib's inscriptions removed, had the bed and throne refurbished, and had those objects clad anew with metal platings bearing Ashurbanipal's own dedicatory inscription.[125] At the same time, Ashurbanipal had a new chariot (narkabtu) made for Babylon's patron god. That exquisite gift was adorned with trappings of gold, silver, and precious stones; the metal plating probably bore (an) Akkadian inscription(s). The bed, throne, and chariot entered Esagil on 27-III-655.[126] The bed was placed in Kaḫilisu ("Gate Sprinkled with Luxuriance"), the bed chamber (maštaku) of Zarpanītu.[127] The dedication of these items by Ashurbanipal might have caused a bit of friction with Šamaš-šuma-ukīn, who was losing patience with his brother's constant interference in internal religious and political affairs of Babylonia. These actions might have widened the rift between the two brothers.

Ashurbanipal also had an ornately-decorated writing board (lēʾu) dedicated to Marduk. Unfortunately, the clay tablet upon which this copy of the text is written is not sufficiently preserved to be able to determine when the text was composed or when the writing board, which bore an image of the Assyrian king, was placed in Esagil.[128]

After the suppression of the Šamaš-šuma-ukīn rebellion (sometime after V-648) and while Kandalānu (647–627) was king of Babylon, Ashurbanipal continued to undertake building projects in Babylon. Probably in 647, he made repairs to Duku ("Pure Mound"), the seat of Marduk as Lugaldimmeranki in Ubšukkina ("Court of Assembly") in Esagil.[129] This part of Babylon's most sacred building might have sustained damage during the Brothers' War. Much later in his reign, around his 30th regnal year (639), Ashurbanipal is known to have sponsored construction at Babylon. Sometime before II-639, he dedicated an (inscribed) and reddish-gold-plated ebony bed to Marduk, renovated a sanctuary of Marduk, and began rebuilding Esabad ("House of the Open Ear"), the temple of the goddess Gula in the Tuba quarter in west Babylon.[130] In 638 (or slightly later, perhaps in 637), construction on Esabad was completed.[131] After finishing Gula's temple, or shortly before completing its construction, Ashurbanipal renovated Marduk's akītu-house, which was located outside of the city, north of the Ištar Gate.[132] In and after 639 and 638, the Assyrian king had utensils of metal and stone, including two gold baskets (masabbu), made for Esagil.[133]

It is possible that Ashurbanipal worked on other temples around this same time, perhaps the Ninurta temple Eḫursagtila ("House Which Exterminates the Mountains"),[134] a sacred building located in Šuanna quarter of east Babylon. Ashurbanipal, or possibly Esarhaddon, might be the unnamed former king who the founder of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, Nabopolassar (625–605), claims had started building the temple but had not completed its construction.[135] If Ashurbanipal was in fact a previous builder of Eḫursagtila, then it is probable that work began on the temple (shortly) before his death in 631, which might explain why it was never finished.[136]

Notes

[91] Four books on this important Mesopotamian city have recently been published. These are Beaulieu, History of Babylon; Radner, A Short History of Babylon; Pedersén, Babylon; and Dalley, City of Babylon.

[92] Grayson and Novotny, RINAP 3/2 pp. 316–317 Sennacherib 223 lines 50b–54a. The event and the period following the second conquest of Babylon are also recorded in the Chronicle Concerning the Period from Nabû-nāṣir to Šamaš-šuma-ukīn, the Esarhaddon Chronicle, the Akītu Chronicle, Babylonian Kinglist A, the Ptolemaic Canon, and the Synchronistic King List. For translations, see Grayson and Novotny, RINAP 3/1 pp. 23–27. Inscriptions of Esarhaddon record the destruction of the city, but those accounts remove all human agency from the events. See, for example, Leichty, RINAP 4 p. 196 Esarhaddon 104 i 34–ii 1a: "The Enlil of the gods, the god Marduk, became angry and plotted evilly to level the land (and) to destroy its people. The river Araḫtu, (normally) a river of abundance, turned into an angry wave, a raging tide, a huge flood like the deluge. It swept (its) waters destructively across the city (and) its dwellings and turned (them) into ruins. The gods dwelling in it flew up to the heavens like birds; the people living in it were hidden in another place and took refuge in an [unknown] land."

[93] Babylon, according the 1,092-line Babylonian Epic of Creation Enūma eliš ("When on high"), had been created to not only be the center of the universe but also the eternal link between humans and gods. For recent editions and studies of Enūma eliš, see Kämmerer and Metzler, Das babylonische Weltschöpfungsepos; and Lambert, Babylonian Creation Myths pp. 3–277 and 439–492. Babylon and Esagil are regularly described as being the bond of heaven and earth in cuneiform sources. See, for example, George BTT pp. 38–39 no. 1 (Tintir = Babylon) Tablet I line 6 and pp. 80–81 no. 5 (Esagil commentary) lines 25–26. For a recent study of Marduk's Babylon linking heaven and earth, see Radner, A Short History of Babylon pp. 75–87.

[94] For a brief study of the murder of Sennacherib, see Grayson and Novotny, RINAP 3/2 pp. 28–29 (with references to earlier studies). For the opinion that Esarhaddon, rather than Urdu-Mullissu, was the son who murdered his father, see also Knapp, JAOS 140 (2020) pp. 165–181. For the most recent discussion on the matter, see Dalley and Siddall, Iraq 83 (2021) pp. 45–56.

[95] Esarhaddon's work on Babylon might have started during his 2nd year (679), after the 28th/29th of Simānu (III). On the date, see Novotny, JCS 67 (2015) pp. 151–152. With regard to work on Esagil, it is possible that that project had not progressed very far by 672 or 671. For this opinion, see Frame, Babylonia pp. 77–78; and George, Iraq 57 (1995) p. 178 n. 38.

[96] For Esarhaddon's "Babylon Inscriptions," see Leichty, RINAP 4 pp. 193–258 Esarhaddon 104–126; and Novotny, JCS 67 (2015) pp. 145–168. See also the "Aššur-Babylon Inscriptions": Leichty, RINAP 4 pp. 103–115 Esarhaddon 48–49 and 51–53 and pp. 134–137 Esarhaddon 60. For Esagil and Etemenanki, see George, House Most High pp. 139–140 no. 967 and p. 149 no. 1088. For Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil, with their eight gates, see George, BTT pp. 336–351 (commentary to Tintir V lines 49–58, which are edited on pp. 66–67).

[97] Leichty, RINAP 4 p. 198 Esarhaddon 104 iii 41b–iv 8. The square-shaped (or diamond-shaped) "Sublime Court" (also known as the "Court of Bel") of Esagil was the earthly replica of the "Field" (ikû), its heavenly counterpart. The Field, which we now refer to as the "Square of Pegasus," was a large diamond shape that was formed by four near-equally-bright stars: Markab ("saddle"; α Pegasi), Scheat ("shoulder"; β Pegasi), Algenib ("the flank"; γ Pegasi) and Alpheratz ("the mare"; α Andromedae); see Radner, A Short History of Babylon pp. 79–81. After 689, Sennacherib built a new square courtyard onto Ešarra, the so-called "Ostanbau" (see Grayson and Novotny, RINAP 3/2 pp. 20–21 [with references to previous studies]); that part of Aššur's temple at Aššur was modelled on Esagil's Sublime Court/Court of Bēl. The statement in Esarhaddon's inscriptions that Marduk's temple was "a replica of Ešarra" refers to the ikû-shaped eastern annex building constructed by Sennacherib. This addition was to make Aššur's temple the new bond between heaven and earth; Leichty, RINAP 4 p. 109 Esarhaddon 48 (Aššur-Babylon A) lines 98b-99a refer to that sacred building as the "bond of heaven and earth" (markas šamê u erṣetim).

[98] Leichty, RINAP 4 p. 207 Esarhaddon 105 vi 27b–32. The base of Etemenanki measured 91.5 × 91.5 m (8400 m²). The core of unbaked mud bricks was surrounded with a 15.75-meter-thick baked-brick outer mantle. Information about Etemenanki prior to the Assyrian domination of Babylonia (728–626) is very sparse and comes entirely from narrative poems (Enūma Eliš and the Poem of Erra) and scholarly compilations (Tintir = Babylon) and, thus, it is not entirely certain when Marduk's ziggurat at Babylon was founded. It has often been suggested that Nebuchadnezzar I (1125–1104), the fourth ruler of the Second Dynasty of Isin, was its founder; this would coincide with the period during which Enūma eliš is generally thought to have been composed. Given the lack of textual and archaeological evidence, this assumption cannot be confirmed with any degree of certainty and one cannot rule out the possibility that the Etemenanki was founded much earlier, perhaps even in Old Babylonian times. Esarhaddon is the first known builder of Marduk's ziggurat. In the reign of the Neo-Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II (604–562), Etemenanki is sometimes thought to have had seven stages, six lower tiers with a blue-glazed-brick temple construction on top; for a discussion and digital reconstructions, see Pedersén, Babylon pp. 153–165. This view has gained support over the last decade because Babylon's ziggurat is depicted on the now-famous "Tower of Babel" Stele (George, CUSAS 17 pp. 153–169 no. 76), however, this understanding is now less certain as that monument might be a modern fake (Dalley, BiOr 72 [2016] col. 754; Lunde, Morgenbladet 2022/29 pp. 26–33; and Dalley, BiOr 79 [2022] forthcoming). Given the current textual and archaeological evidence, it is uncertain how many stages Marduk's ziggurat had during Esarhaddon's reign. For further details about the textual sources and the archaeological remains, see Wetzel and Weissbach, Hauptheiligtum; George, BTT pp. 298–300 (the commentary to Tintir IV line 2, which is edited on pp. 58–58) and 430–433 (commentary to the E-sagil Tablet lines 41–42, which are edited on pp. 116–117); and Pedersén, Babylon pp. 142–165.

[99] Leichty, RINAP 4 p. 207 Esarhaddon 105 vi 33–vii 4. According to Esarhaddon's inscriptions, Babylon's city walls formed a perfect square; however, the northern and southern stretches of the wall are 2,700 m in length, while the eastern and western sides are significantly shorter, being each 1,700 m in length. According to an inscription of the Neo-Babylonian king Nabonidus (Weiershäuer and Novotny, RINBE 2 p. 54 Nabonidus 1 [Imgur-Enlil Cylinder] i 22), Imgur-Enlil measured "20 UŠ." An UŠ is a unit for measuring length, but its precise interpretation is uncertain since the sections of the lexical series Ea (Tablet VI) and Aa dealing with UŠ are missing. According to M. Powell (RLA 7/5–6 [1989] pp. 459 and 465–467 §I.2k), 1 UŠ equals 6 ropes, 12 ṣuppu, 60 nindan-rods, 120 reeds, and 720 cubits, that is, approximately 360 m; for UŠ = šuššān, see Ossendrijver, NABU 2022/2 pp. 156–157 no. 68. According to the aforementioned inscription of Nabonidus, Imgur-Enlil measured 20 UŠ (UŠ.20.TA.A), which would be approximately 7,200 m (= 360 m × 20). A.R. George (BTT pp. 135–136) has demonstrated that the actual length of Imgur-Enlil in the Neo-Babylonian period was 8,015 m, while O. Pedersén (Babylon p. 42 and 280) gives the length of the walls as 7,200 m, with the assumption that the stretches of walls within the area of palace are disregarded. In the time of Nabopolassar and his son Nebuchadnezzar II, Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil were respectively 6.5 m and 3.7 m thick, with reconstructed heights of 15 m and 8 m. These impressive structures would have been made from an estimated 96,800,000 (Imgur-Enlil) and 28,500,000 (Nēmeti-Enlil) unbaked bricks. For a recent study of Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil from the textual sources and the archaeological remains, see Pedersén, Babylon pp. 39–88.

[100] For Eniggidrukalamasuma, see George, House Most High pp. 132–133; and Pedersén, Babylon pp. 167–174. Moreover, Esarhaddon (and Ashurbanipal) built a baked-brick pedestal or altar in front of the larger, eastern gate to the ziggurat area, ca. 190 m from the precinct wall. For the baked-brick pillar, see Reuther, Merkes pp. 70–71; and Pedersén, Babylon pp. 154–155 and p. 213 fig. 5.14. Furthermore, it has been suggested that Esarhaddon was the king responsible for the "lion of Babylon"; for this proposal, see Dalley, City of Babylon pp. 201 and p. 202 fig. 7.9; and Dalley, BiOr 79 (2022) forthcoming.

Because Esarhaddon states that he refurbished the statues of Bēlet-Bābili (Ištar), Ea, and Mandānu, together with those of Marduk and Bēltīya (Zarpanītu), he presumably also undertook work on the temples of those three deities: respectively Eturkalama ("House, Cattle-Pen of the Land"), Ekarzagina ("House, Quay of Lapis Lazuli" or "House, Pure Quay"), and Erabriri ("House of the Shackle Which Holds in Check"). This proposal is supported by the fact that Ashurbanipal is known to have sponsored construction on Eturkalama and Ekarzagina; see below. All three temples were located inside the Esagil complex.

[101] Esarhaddon never took the hand of Marduk during an akītu-festival (New Year's festival) and, therefore, he was never officially regarded as Marduk's divinely-appointed earthly representative. This was because Marduk's statue was damaged and in Baltil (Aššur), probably in the Aššur temple. For these reasons, all of his "Babylon Inscriptions" written on clay prisms are dated to his "accession year" (rēš šarrūti). For details, see Novotny, JCS 67 (2015) pp. 149–151.

[102] Leichty, RINAP 4 pp. 107–108 Esarhaddon 48 (Aššur-Babylon A) lines 61b–93; compare p. 198 Esarhaddon 104 (Babylon A) iv 9–20. The statues of the deities Amurru, Abšušu, and Abtagigi were also renovated/repaired at that time. A seat (šubtu) and footstool (gišzappu) for the goddess Tašmētu were chief among the items that Esarhaddon had made or restored for Babylon.

[103] Several inscriptions of Esarhaddon prematurely record Marduk's triumphant return to Esagil and the installation of Šamaš-šuma-ukīn as king of Babylon. See Leichty, RINAP 4 p. 113 Esarhaddon 52 (Aššur-Babylon H) and pp. 114–115 Esarhaddon 53 (Aššur-Babylon G). Esarhaddon likely planned to return Marduk and his entourage in time for the fall akītu-festival at Babylon, the one held in the month Tašrītu (VII), in 670 (his 11th regnal year as the king of Assyria). Those plans, however, were derailed when the king ordered an intercalary Ulūlu (VI₂) to be added, thus postponing the New Year's festival in Babylon by one entire month; this is recorded in K 930, a letter attributed to the chief exorcist Marduk-šākin-šumi addressed to the king (Parpola, SAA 10 p. 200 no. 253). S. Parpola (LAS 2 pp. 185–188 no. 190) dates this piece of correspondence to 1-VI-670 (= August 7th 670), an interpretation that was perhaps (at least partially) influenced by the contents of 81-1-18,54 (Cole and Machinst, SAA 13 pp. 54–55 no. 60), a letter attributed to Urdu-Nabû, a priest of the Nabû temple at Kalḫu, who pressed the king about whether or not the akītu-festival would take place since nobles from Babylon and Borsippa had come to him asking about the matter. The decision to intercalate Ulūlu (VI₂), rather than Addaru (XII₂), seems to have taken place at the outset of Ulūlu, despite the fact that Esarhaddon's advisors were aware that 670 would be a "leap year" from the beginning of the year, although it was unclear at that time whether the intercalation would take after Ulūlu or Addaru; see K 185 (Parpola, SAA 10 pp. 32–33 no. 42), a letter written by the astrologer Balasî, probably in Nisannu (I) of that year. The slight shift in the calendar meant that the Tašrītu (VII) 670 akītu-festival did not take place and, thus, Esarhaddon did not escort Marduk and his entourage to Babylon, take the hand of Babylon's tutelary deity during the New Year's festival, and officially become the king of Babylon as he had intended. The inscriptions written on tablet fragments Sm 1079 (Aššur-Babylon H) and K 5382b (Aššur-Babylon G) were likely written shortly before Esarhaddon ordered an intercalary Ulūlu, resulting in him not returning Marduk to Esagil and not placing Šamaš-šuma-ukīn on the throne of Babylon as those texts recorded.

Of course, other factors might have also contributed to Esarhaddon not returning Marduk to Esagil. One postponement might have been due to an inauspicious event that occurred in the fortified city Labbanat, which prompted Esarhaddon to order that the statues be returned to Assyria rather than continuing the journey to Babylon; for some details on K 527 (Parpola SAA 10 p. 19 no. 24) — a letter written by Ištar-šumu-ēreš, Adad-šumu-uṣur, and Marduk-šākin-šumi, possibly on 18-II-669 — see Frame, Babylonia pp. 77–78. Moreover, the restoration of Esagil might not have been sufficiently completed to have warranted the return of the cult statues. This might have been due in part to the fact that Esarhaddon's architects had not sufficiently raised the temple above the water table and that Esagil's inadequately waterproofed floor needed to be fixed. This problem with the temple's flooring is suggested by the fact that Ashurbanipal raised the level of the pavement in Esagil's main courtyard by nearly a half meter; see the comments in George, Iraq 57 (1995) p. 178 n. 48. Moreover, Esarhaddon's decision to campaign against Egypt for a third time in 669 might have also delayed the return of Marduk's statue.

[104] For a brief overview, see Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 pp. 13–14.

[105] Late in Nisannu (I) 668, Ashurbanipal instructed his diviners to determine whether Šamaš-šuma-ukīn should take the hand of Marduk during that year and take that god's statue back to Babylon; see Starr, SAA 4 pp. 236–237 no. 262. On 28-I-668, the king's haruspices returned with a 'firm yes' from the gods Šamaš and Marduk and the journey to Babylon set out shortly thereafter. According to three Babylonian Chronicles, Šamaš-šuma-ukīn and Marduk entered Babylon in the month Ayyāru (II). The Chronicle Concerning the Period from Nabû-nāṣir to Šamaš-šuma-ukīn (iv 34–36) records that the entry into Babylon took place on either the 14th or 24th day of the month, while the Esarhaddon Chronicle (lines 35´–37´) states that that event occurred on the 24th or 25th of Ayyāru, and the Akītu Chronicle (lines 5–8) mentions that Šamaš-šuma-ukīn and Marduk came into Babylon on the 24th. See Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 pp. 34–35 for translations of these passages.

[100] Jeffers and Novotny, RINAP 5/2 p. 326 Asb. 220 (L4) iii 1´–22´ (with restorations from iv 8´–20´ on p. 328). Note that iii 1´–6´ are presented here as they would have appeared on the now-lost stele that Ashurbanipal had set up in Esagil after Marduk's return to his temple in II-668, rather than as how these lines of texts were inscribed in the draft version preserved on clay tablet K 2694+. For details, see Jeffers and Novotny, RINAP 5/2 pp. 5–6, 320–321, 326, and 328.

[107] Perhaps already in VII-670; see n. 103 above. As pointed out by G. Frame (Babylonia p. 78), the promotion of Šamaš-šuma-ukīn to heir designate of Babylon in II-672 might have prompted the return of Marduk's statue.

[108] This work is recorded in Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 pp. 103–104 Asb. 5 (Prism I) i 8´–ii 5; pp. 111 and 114 Asb. 6 (Prism C) i 18´–43´; p. 139 Asb. 7 (Prism Kh) i 1´–13´; pp. 212 and 216 Asb. 10 (Prism T) i 21–54; pp. 266–267 Asb. 12 (Prism H) i 1´–3´; pp. 275 and 278 Asb. 13 (Prism J) ii 1´–14´ and viii 12´–17´; p. 282 Asb. 15 ii 10–21; p. 285 Asb. 17 i´ 6´–9´; p. 293 Asb. 22 i 1´–4´; pp. 302–303 Asb. 23 (IIT) lines 41–53; and p. 355 Asb. 61 lines 13–33; Jeffers and Novotny, RINAP 5/2 p. 84 Asb. 98 i 1´–6´; p. 85 Asb. 99 i 1´–11´; p. 111 Asb. 116 i 2´–9´a; p. 238 Asb. 191 rev.? 1–15; pp. 307–308 Asb. 215 (Edition L) i 1´–25´; p. 318 Asb. 219 obv. 1´–12´; p. 331 Asb. 222 lines 7–14a; pp. 333–334 Asb. 223 iii 36´–40´ and iv 11´–19´; pp. 337–338 Asb. 224 lines 26–32; p. 342 Asb. 225 rev. 24´; p. 343 Asb. 226 rev. 3–7; and 354 Asb. 229 i 1´–9´; and, in the present volume, Asb. 241 lines 3–22; Asb. 242 lines 7b–20a; Asb. 243 lines 7b–11; Asb. 244 lines 8–14a; Asb. 245 lines 8–14a; Asb. 246 lines 36b–67a; Asb. 247–251; Asb. 253 lines 7–18; Asb. 254 lines 1–32; Asb. 262 lines 1–15; and Asb. 263 lines 7–22a. For the archaeological evidence, see Pedersén, Babylon passim. A.R. George (Iraq 57 [1995] p. 178 n. 38) has proposed the following about the state of Esagil's completion at the very beginning of Ashurbanipal's reign: "[M]ost, if not all, of the basic work must have been completed by the time that the cult-statues eventually returned to Babylon, at the accession of Šamaš-šuma-ukīn in 668 B.C., although some furnishings, notably Marduk's bed and chariot, were not installed until much later (654 and 653 B.C. respectively). Though six months elapsed between the death of Esarhaddon and Šamaš-šuma-ukīn's arrival in Babylon with the cult-statue of Marduk, it remains unlikely that the walls of the central courtyard and other structural parts of the main building had yet to be built at the time of Aššurbanipal's accession. What is probable, however, is that some, if not all, of the secondary brickwork known to have been the work of Aššurbanipal, rather than his father — the raising and repaving of the floors, and maybe the addition of the kisû on the exterior walls — dated to this time."

[109] Esagil and Etemenanki were located in the Eridu quarter of Babylon, not in Šuanna as Ashurbanipal's inscriptions record.

[110] This work is attested from numerous bricks with a nine-line Akkadian inscription (Asb. 247) stamped into them. They come from Floor k (3rd pavement) and Floor l (4th pavement); see Pedersén, Babylon p. 143; and the catalogue of Asb. 247 in the present volume.

[111] George, House Most High p. 156 no. 1176.

T[112] he wood was probably supplied by one or more of Assyria's vassals in the Levant. It is possible that Baʾalu of Tyre, Milki-ašapa of Byblos, Iakīn-Lû (Ikkilû) of Arwad, and Abī-Baʾal of Samsimurruna aided in the transport of the timber since Mount Amanus and Mount Lebanon were in their spheres of influence.

[113] On the identification of musukkannu-wood as Dalbergia sissoo, see, for example, Postgate, BSA 6 (1992) p. 183.

[114] George, House Most High p. 108 no. 569, p. 119 no. 715 and p. 151 no. 1117. For Emaḫ, see also Pedersén, Babylon pp. 181–189. Ekarzagina and Eturkalama were located in the Esagil temple complex, whereas Emaḫ was in the Ka-dingirra district, which was north of the Eridu district. Although Ashurbanipal states that he built Ekarzagina and Eturkalama anew (Asb. 244 and 246), it is possible that Esarhaddon had already taken some steps to renovate those two temples. This is suggested by the fact that Ashurbanipal's father states that he refurbished the statues of Bēlet-Bābili (Ištar) and Ea, together with those of Marduk, Bēltīya (Zarpanītu), and Mandānu. Because Ashurbanipal reports that these two religious structures were "built anew" (eššiš ušēpiš), it is quite possible that little had been accomplished on Ekarzagina's and Eturkalama's rebuilding during Esarhaddon's reign and, therefore, Ashurbanipal felt that he could take full credit for these two temple's reconstructions; note also that he does not refer to his father's work on Babylon's city walls. Because the passage recording Marduk's return in the so-called "School Days Inscription" refers to the area of Ea's temple as Karzagina ("Quay of Lapis Lazuli"), instead of Ekarzagina ("House, Quay of Lapis Lazuli"), like his father Esarhaddon does, one could tentatively suggest that the brick structure of Ekarzagina had not been built by II-668 and, therefore, Ashurbanipal's statement about him constructing Ea's temple anew was not unfounded; compare Jeffers and Novotny, RINAP 5/2 p. 327 Asb. 220 [L⁴] iii 19´ to Leichty, RINAP 4 Esarhaddon 60 (Aššur-Babylon E) line 46´. In addition, it is likely that Ashurbanipal also worked on Erabriri ("House of the Shackle Which Holds in Check"), the temple of the god Mandānu, which was inside the Esagil temple complex, since that deity's statue was returned to Babylon in II-668; see George, House Most High p. 137 no. 936.

[115] Asb. 241 (lines 16b–22) does not refer at all to his father's work on Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil. That text records that Ashurbanipal rebuilt (that section of) Babylon's inner and outer walls because they had become old and had buckled or collapsed. This might imply that Esarhaddon had not yet started work on that stretch of Imgur-Enlil and Nēmetti-Enlil or that the work was still in the early stages of construction. Cyrus II, in his so-called "Cyrus Cylinder Inscription" (Schaudig, Inschriften Nabonids pp. 550–556), mentions that he discovered foundation documents of Ashurbanipal in the mudbrick structure of Babylon's walls when he was rebuilding them.

[116] None of Babylon's eight city gates are mentioned by name in Ashurbanipal's inscriptions. These gates, starting with the southwesternmost gate of east Babylon, and moving counterclockwise, are the Uraš Gate (Ikkibšu-nakarī), the Zababa Gate (Izēr-âršu), the Marduk Gate (Šuʾâšu-rēʾi), the Ištar Gate (Ištar-sākipat-tēbîšu), the Enlil Gate (Enlil-munabbiršu), the King's Gate (Libūr-nādûšu), the Adad Gate (Adad-napišti-ummāni-uṣur), and the Šamaš Gate (Šamaš-išid-ummāni-kīn).

[117] In Asb. 3 (Prism B) ii 26–34a (Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 61), for example, Ashurbanipal states: "[Si]lver, gold, precious stones, as much property of his palace as there was, garment(s) with multi-colored trim, linen garments, large horses, people — male and female — two tall obelisks cast with shiny zaḫalû-metal, whose weight was 2,500 talents (and which) stood at a temple gate, I ripped (them) from where they were erected and took (them) to Assyria. I carried off substantial booty, (which was) without number, from inside the city Thebes."

[118] The two obelisks were removed from a temple at Thebes (possibly the Amun temple at Karnak). Some scholars have suggested that the (seven-meter-tall) obelisks were solid metal and date to the reign of Tuthmosis III (1504–1450). For this opinion, see, for example, Desroches-Noblecourt, Revue d'Égyptologie 8 (1951) pp. 47–61; Aynard, Prisme pp. 23–25; Kitchen, Third Intermediate Period4 p. 394 (with n. 891); and Onasch, ÄAT 27/1 p. 158. Note that A.L. Oppenheim (ANET3 p. 295 n. 13) has proposed that the obelisks were only metal plated.

According to M.A. Powell (RLA 7/7–8 [1990] p. 510 §V.6), one talent was approximately thirty kilograms (= sixty minas). Thus, each obelisk might have weighed about 75,000 kg (165,346 lbs) and, therefore, the pair might have yielded around 150,000 kg (330,693 lbs) of zaḫalû-metal. At least seventy talents (2,100 kg/4630 lbs) of that silver alloy was used to decorate the cella of the moon-god Sîn's temple Eḫulḫul; see Novotny, Studia Chaburensia 8 pp. 78–80; and Jeffers and Novotny, RINAP 5/2 p. 25 (with n. 109).

[119] As for the Dais of Destinies (parak šīmāte), Esarhaddon (Leichty, RINAP 4 p. 136 Esarhaddon 60 lines 26´–29´a) records that he had it entirely rebuilt from ešmarû-metal and had images of both him and his son Ashurbanipal (then heir designate) depicted on its outer facing. For further details, see Grayson and Novotny, RINAP 3/2 pp. 21–22 (esp. n. 56).

[120] George, BTT pp. 44–45 no. 1 (Tintir) Tablet II line 1. According to A.R. George (ibid. pp. 268–269), "Tiʾāmat" was the seat of Marduk (Bēl) in Eumuša, the cella of Marduk in Esagil. According to Asb. 15 ii 19–21 (Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 282), the throne-dais was "[placed over the massive body of the ro]iling [sea (Tiāmat)]."

[121] For the opinion that the zaḫalû-metal came from the obelisks plundered from Thebes, see Onasch, ÄAT 27/1 p. 80 n. 386 and pp. 156–158 and 161; and Novotny, Orientalia NS 72 (2003) pp. 211–215.

[122] During his final years on the throne (late 689–681), Sennacherib instituted numerous religious reforms, the foremost being the remodeling of the temple, cult, and New Year's festival of the god Aššur at Aššur on those of Babylon, and having Assyrian scribes (re)write Enūma eliš so that the Assyrian Empire's national god, rather the Babylon's tutelary deity Marduk, was the chief protagonist and the city of Aššur, instead of Babylon, was the bond that held the universe together. For Sennacherib's religious reforms, see in particular Machinist, Wissenschaftskollegs zu Berlin Jahrbuch (1984–85) pp. 353–364; Frahm, Sanherib pp. 20 and 282–288; and Vera Chamaza, Omnipotenz pp. 111–167.

[123] These texts were dedicatory inscriptions, with Aššur as the divine recipient. For the inscription(s) written on the appropriated bed and throne of Marduk, see Grayson and Novotny, RINAP 3/2 p. 227 Sennacherib 161 lines 1–20 and pp. 229–231 Sennacherib 162 ii 1–iii 16´. According to the subscript of Sennacherib 161 (Grayson and Novotny, RINAP 3/2 p. 228 rev. 9´–11´), the same inscription was written on the throne. That scribal note also states that the text written on a chest (pitnu) was not copied. The two tablets bearing these texts were inscribed by Ashurbanipal's scribes in 656 or in early 655, sometime before 27-III-655. For details, see Grayson and Novotny, RINAP 3/2 p. 8 and 225–229; and Jeffers and Novotny, RINAP 5/2 pp. 8–9.

[124] For the texts, see the note immediately above. For the description of the bed, see Grayson and Novotny, RINAP 3/2 p. 228 Sennacherib 161 rev. 1´–2´ and p. 231 Sennacherib 162 iii 17´–29´. For that of Marduk's throne, see ibid p. 228 Sennacherib 161 rev. 3´–8´ and p. 231 Sennacherib 162 iii 30´–35´.

[125] For a copy of that text, see Jeffers and Novotny, RINAP 5/2 pp. 333–334 Asb. 223 iv 1´–29´. K 2411, the tablet inscribed with that text, was composed shortly after 27-III-655.

[126] For the date, see Jeffers and Novotny, RINAP 5/2 p. 333 Asb. 223 iii 36´–40´: "Wording (of the inscription) that was erased from the bed (and) the throne of the god Bēl (Marduk), which were deposited in the temple of (the god) Aššur, (and that of the inscription) written upon (them) in the name of Ashurbanipal. Simānu (III), the twenty-seventh day, eponymy of Awiānu (655), th[ey were returned t]o Ba[byl]on [(...)]." Marduk's throne is not specifically mentioned or referred to in Ashurbanipal's own inscriptions. This is in contrast to the bed and the chariot, which are regularly mentioned in the prologues of that king's inscriptions. See, for example, Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 216 Asb. 10 (Prism T) i 39–54.

The Šamaš-šuma-ukīn Chronicle (Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 pp. 34–35) line 4 records that the "former bed of the god Bēl" returned to Babylon in the 14th year. The text, at least according for the entry for the 4th year (lines 2–3), should be dated by the regnal years of Šamaš-šuma-ukīn, and, therefore, the return of Marduk's bed occurred in 654 (Šamaš-šuma-ukīn 14th year = Ashurbanipal's 15th year), which is a year later than is recorded by contemporary inscriptions (Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 pp. 354–256 Asb. 61; and Jeffers and Novotny, RINAP 5/2 p. 333 Asb. 223 iii 36´–40´), which state that the bed (and throne) of Marduk were returned early in the eponymy of Awiānu, governor of Que. That official, at least according to the so-called "Eponym Lists" (Millard, SAAS 2 p. 53 sub 655 A3 v 5´), was limmu in Ashurbanipal's 14th regnal year (655). It is not impossible that the author/compiler of the Šamaš-šuma-ukīn Chronicle confused Šamaš-šuma-ukīn's and Ashurbanipal's regnal years, and wrote down 14th year (which would be correct for the Assyrian king, but not for the king of Babylon) rather than 13th year (which would be correct for the king of Babylon, but not for the king of Assyria). The same confusion seems to have taken place for the 15th year in line 5 (of the Šamaš-šuma-ukīn Chronicle). The scribe dates the entry of the "new chariot of the god Bēl" to the 15th year, which surely must be to Ashurbanipal's 15th year as king (654 = Year 14 of the king of Babylon), rather than Šamaš-šuma-ukīn's 15th regnal year (653).

The date for the entry of Marduk's new chariot into Babylon seems to conflict with two inscriptions of Ashurbanipal, which imply that the chariot was already given to Marduk in 655, probably before 27-III of that year. The inscriptions in question are Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 pp. 354–256 Asb. 61; and Jeffers and Novotny, RINAP 5/2 pp. 331–334 Asb. 223, which were written in VII-655 and shortly after 27-III-655 respectively. Assuming that Ashurbanipal dedicated the chariot at the same time as Marduk's bed, as that king's inscriptions suggest, then the compiler of the Šamaš-šuma-ukīn Chronicle, for reasons unknown, recorded the receipt of the Assyrian king's donations to Marduk in two separate and sequential years, rather than in one and the same year. This (arbitrary) splitting of events over two years also happens for entries in the Babylonian Chronicle for Esarhaddon's 4th and 5th regnal years (677 and 676). In the Chronicle Concerning the Period from Nabû-nāṣir to Šamaš-šuma-ukīn and the Esarhaddon Chronicle (Leichty, RINAP 4 pp. 7–8), the decapitations of Abdi-Milkūti of Sidon and Sanda-uarri of Kundu and Sissû are erroneously recorded as taking place at the end of the 5th year (676), rather than at the end of the 4th year (677), after the capture of the Phoenician city Sidon. It is clear from Esarhaddon's own inscriptions, in particular, "Nineveh B" (Leichty, RINAP 4 pp. 27–35 Esarhaddon 2), that Abdi-Milkūti and Sanda-uarri were beheaded in late 677. It is certain since the earliest known copy of that text (ex. 1 [IM 59046]) is dated to 22-II-676, which is over four months before VII-676 and XII-676, when those rulers lost their heads according to the chronicles. That error in dating in the Babylonian Chronicle has been long known; see, for example, Tadmor, Studies Grayson p. 272. The entries for the return of Marduk's bed and entry of his new chariot into Babylon might contain a similarly erroneous account of events.

[127] George, House Most High p. 107 no. 555. Kaḫilisu is a byname of Eḫalanki ("House of the Secrets of Heaven and Netherworld") and named in Ashurbanipal's inscriptions instead of Edaraʾana ("House of the Ibex of Heaven"), the actual name of the cella of Zarpanītu in Esagil. The destinations of the throne and chariot are not recorded in Ashurbanipal's inscriptions.

[128] Clay tablet 81-7-27,70 = Jeffers and Novotny, RINAP 5/2 pp. 342–343 Asb. 226.

[129] George, House Most High p. 77 no. 180 and p. 154 no. 1160. The full names of Duku and Ubšukkina are Dukukinamtartarrede ("Pure Mound Where Destinies are Determined") and Ubšukkinamezuhalhala ("Court of the Assembly Which Allots the Known Mes"). The byname of Duku is parak šīmāti ("Dais of Destinies").

[130] The ebony bed and the sanctuary (ayyakku) are both mentioned in Asb. 22 (i 1´–4´; Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 pp. 293), an inscription whose approximate date of composition is ca. 642–640. Work on Gula's temple was presumably underway when Asb. 12 (Prism H; ibid. pp. 265–271) was composed. The principal copy of that text (EŞ 7832), whose now-lost building account would have recorded the rebuilding of Esabad, was inscribed on 6-II-639.

[131] Esabad was completed before Asb. 13 (Prism J: Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 pp. 271–278) and Asb. 23 (IIT; ibid. pp. 296–311) were composed. Those two texts were written no earlier than Ashurbanipal's 31st regnal year (638). The date of Prism J is not preserved on any of the known exemplars of that text and the limestone slab engraved with the IIT text is not dated.

[132] The Sumerian ceremonial name of the akītu-house at Babylon is Esiskur ("House of the Sacrifice"); see George, House Most High p. 142 no. 993. Work on the temple was in progress when Asb. 13 (Prism J; Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 pp. 271–278) was composed and, thus, it might have been completed in 638 (or in 637), perhaps before the fall New Year's festival in the month Tašrītu (VII).

[133] One of the baskets was inscribed with a fifty-line inscription, while the other had a fifty-five-line text written on it. These Akkadian inscriptions are Asb. 224 and 225 respectively, which were composed sometime after 638 since they mention the Cimmerian ruler Tugdammî's successor Sandak-šatru; see Jeffers and Novotny, RINAP 5/2 pp. 334–342.

[134] George, House Most High p. 102 no. 489; and Pedersén. Babylon pp. 190–193.

[135] Weisershäuser and Novotny, RINBE 1/1 Nabopolassar 7 (Eḫursagtila Cylinder) lines 22–24; see also Da Riva, SANER 3 pp. 54 §2.2.2 (É-PA-GÌN-ti-la Inscription [C12]).

[136] No remains of this stage of the temple's history ("Level 0") have been excavated. The earliest phase of construction ("Level 1") dates to the time of Nabopolassar. See Pedersén. Babylon pp. 190–193 for details. Note that a single brick inscribed with a Sumerian inscription of Esarhaddon (BE 15316; Leichty, RINAP 4 pp. 256–258 Esarhaddon 126 ex. 1) was discovered in the Ninurta temple, in the South gate, courtyard door, which might point to Esarhaddon having worked on Eḫursagtila. Despite Aššur-etel-ilāni's short reign (see below), one cannot entirely exclude the possibility that he, rather than his father or grandfather, undertook construction on Ninurta's temple at Babylon. Given the current textual record, it seems more likely that the unnamed previous building of that sacred structure was Ashurbanipal.

Jamie Novotny

Jamie Novotny, 'Babylon', RINAP 5: The Royal Inscriptions of Ashurbanipal, Aššur-etel-ilāni, and Sîn-šarra-iškun, The RINAP/RINAP 5 Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, 2023 [http://oracc.org/rinap/rinap5/rinap53introduction/buildinginbabylonia/babylon/]