Aššur-etel-ilāni and His Chief Eunuch Sîn-šuma-līšir

When Ashurbanipal died, a certain Nabû-rēḫtu-uṣur incited a rebellion. The chief eunuch Sîn-šuma-līšir and men from his estate, including his cohort commander Ṭāb-šār-papāḫi, brought order back to the Assyrian heartland and installed Ashurbanipal's young and inexperienced son Aššur-etel-ilāni (630–627) on the throne.[203] Aššur-etel-ilāni, whose short reign is not well documented in contemporary or later sources, was king for four years, at least according to one economic text from Nippur.[204]

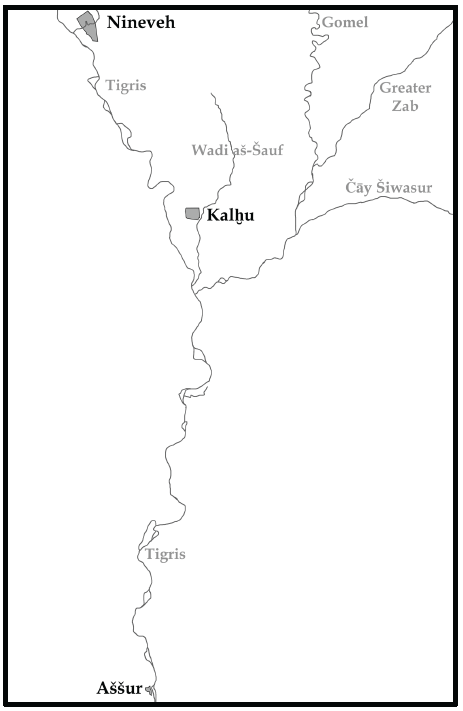

Map showing the principal Assyrian cities where Aššur-etel-ilāni and Sîn-šarra-iškun undertook building activities.

In Assyria, he sponsored construction on Ezida ("True House"), the temple of the god Nabû at Kalḫu.[205] Since his brother and successor Sîn-šarra-iškun (see below) also undertook work on that sacred building, construction on that temple appears to have been unfinished when Aššur-etel-ilāni's tenure as king came to an end.

Despite Kandalānu being the king of Babylon, Aššur-etel-ilāni held authority over parts of Babylonia,[206] and, like his father before him, he sponsored building projects in several Babylonian cities. This is evident from a few of his inscriptions.[207] These record that he dedicated a musukkannu-wood offering table to the god Marduk (presumably at Babylon); made a gold scepter for Marduk and had it placed in Eešerke, that god's place of worship in the city Sippar-Aruru;[208] renovated E-ibbi-Anum ("House the God Anu Named"), the temple of the god Uraš and the goddess Ninegal at Dilbat; and rebuilt Ekur ("House, Mountain"), the temple of the god Enlil at Nippur. In addition, the young Assyrian king returned the body of Šamaš-ibni, a Chaldean sheikh who had been taken to Assyria and executed by Esarhaddon in 678, to Dūru-ša-Ladīni, a fortified settlement in the area of the Bīt-Dakkūri tribe.[209]

Although Aššur-etel-ilāni was king, it was Sîn-šuma-līšir, his chief eunuch, who held real power over Assyria.[210] This might have led to friction between the king's top officials and members of the royal family. In 627 (or possibly already in 628), civil war broke out. The ambitious Sîn-šuma-līšir, who was not a member of the royal family,[211] declared himself king and took control of (parts of) Assyria, as well as parts of Babylonia, which he was able to do since Kandalānu, the king of Babylon, had recently died.[212] Aššur-etel-ilāni, Sîn-šuma-līšir, Sîn-šarra-iškun (another son of Ashurbanipal), and perhaps a few other members of the royal family vied for power in the Assyrian heartland and in Babylonia.[213] Sîn-šarra-iškun, Aššur-etel-ilāni's brother, eventually won the day, ascended the Assyrian throne, and restored order to his kingdom.[214] Sîn-šuma-līšir, who is probably to be identified with the "all-powerful chief eunuch" (rab ša rēši dandannu) of the "Nabopolassar Epic," appears to have gone to Babylonia, where he was captured and publicly executed on the orders of Nabopolassar, a "son of a nobody" who would soon become the next king of Babylon.[215]

Notes

[203] Two grants of land with tax exemptions (Kataja and Whiting, SAA 12 pp. 36–41 nos. 35–36) record that Sîn-šuma-līšir aided Aššur-etel-ilāni, who was still a minor when Ashurbanipal died. Kataja and Whiting, SAA 12 pp. 38–39 no. 36 obv. 4–9 read: "After my father and begetter had dep[arted], no father brought me up or taught me to spread my [wings], no mother cared for me or saw to my [education], Sîn-šuma-līšir, the chief eunuch, [one who had deserved well] of my father and be[getter, who had led me constantly like a father, installed me] safely on the throne of my father and begetter [and made the people of Assyria, great and small, keep] watch over [my kingship during] my minority, and respected [my royalty]." For further information about Sîn-šuma-līšir, see, for example, J. Oates, CAH2 3/2 pp. 162–163, 168–170, and 172–176; Naʾaman, ZA 81 (1991) pp. 243–257; Frame, RIMB 2 p. 269 B.6.36; Mattila, PNA 3/1 p. 1148 sub Sīn-šumu-lēšir; Fuchs, Studies Oelsner pp. 54–58 §3.1; and Schaudig, RLA 12/7–8 (2011) pp. 524–525.

[204] For biographical sketches of Ashurbanipal's first successor, see, for example, J. Oates, CAH2 3/2 pp. 162–176, 184, and 186; Frame, RIMB 2 p. 261 B.6.35; Brinkman, PNA 1/1 pp. 183–184 sub Aššūr-etel-ilāni no. 2; and Fuchs, Studies Oelsner pp. 54–58 §3.1. Because his reign was contemporaneous with that of Kandalānu, Aššur-etel-ilāni is not included in the various lists of rulers of Babylonia, which state that Sîn-šuma-līšir (and Sîn-šarra-iškun) or Nabopolassar was king of Babylon after Kandalānu; see Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 pp. 29–30.

According to CBS 2152, an economic document from Nippur (Brinkman and Kennedy, JCS 35 [1983] p. 53 no. M.12), Aššūr-etel-ilāni was king until at least 1-VIII-627. Note, however, that the pseudo-autobiographical text of Adad-guppi, the mother of the Babylonian king Nabonidus (555–539), from Ḫarrān (Weiershäuser and Novotny, RINBE 2 p. 225 Nabonidus 2001 [Adad-guppi stele] i 30) states that Aššur-etel-ilāni was king for only three years; see above for details.

[205] Aei 1. Twenty-six exemplars of this seven-line Akkadian inscription are presently known. For an overview of the building history of the Ezida temple at Kalḫu, see George, House Most High p. 160 no. 1239; and Novotny and Van Buylaere, Studies Oded pp. 215 and 218. For a discussion of the archaeological remains of that temple, see, for example, D. Oates, Iraq 19 (1957) pp. 26–39; and D. Oates and J. Oates, Nimrud pp. 111–123. For information on Kalḫu, see in particular D. Oates and J. Oates, Nimrud; and the open-access, Oracc-based Nimrud: Materialities of Assyrian Knowledge Production website (http://oracc.org/nimrud [last accessed January 25, 2023).

[206] Although none of Aššur-etel-ilāni's inscriptions ever specifically call him "king of Babylon," "governor of Babylon," or "king of Sumer and Akkad," his authority over (the northern) parts of Babylonia is evident from that fact that twelve economic documents from Nippur are dated by his regnal years, rather than those of Kandalānu. For a catalogue of these texts, which refer to him as either "the king of Assyria" or "the king of the lands," see Brinkman and Kennedy, JCS 35 (1983) pp. 52–53 nos. M.1–M.12.

[207] Aei 2–5.

[208] This temple, whose Sumerian ceremonial name means "House, Shrine of Weeping," is not otherwise attested and it might be a corrupted writing of Ešeriga ("House Which Gleans Barley"), the temple of the deity Šidada at Dūr-Šarrukku (= Sippar-Aruru); see George, House Most High p. 83 no. 269.

[209] Aei 6. For further information about Šamaš-ibni, See Frame, Babylonia pp. 79–80; and p. 165 of the present volume.

[210] See n. 203 above.

[211] As pointed out by E. Frahm (Companion to Assyria p. 198 n. 22), Sîn‐šuma‐līšir's "family background remains unknown and ... it cannot be entirely excluded that he too was a member of the royal family."

[212] This is evident from the fact that Babylonian King List A and the Uruk King List name him as Kandalānu's successor (see Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 29) and that seven economic documents from Babylon and Nippur (Brinkman and Kennedy, JCS 35 [1983] pp. 53–54 nos. N.1–N.7) are dated by his accession year. The latest firmly dated text from Kandalānu was written on 8-III-627 (ibid. p. 48 no. L.159), although it is possible that that document could have been drafted shortly after that king of Babylon's death since the earliest dated Babylonian economic document for Sîn‐šuma‐līšir is 12-III-627.

[213] Since one document from Nippur is dated to 1-VIII of Aššur-etel-ilāni's 4th regnal year (Brinkman and Kennedy, JCS 35 [1983] p. 53 no. M.12) — which is later than the earliest-known economic documents dated by the accession years of Sîn‐šuma‐līšir and Sîn-šarra-iškun, which are dated to the 12th of Simānu (III) and the 8th of Tašrītu (VII) respectively (ibid. pp. 53–54 nos. N.1 and O.1) — it is certain that Aššur-etel-ilāni was still alive when the civil war broke out. It is unclear, however, who set the civil war in motion: Sîn‐šuma‐līšir, Sîn-šarra-iškun, or someone else.

It is possible that Sîn-šarra-iškun, with the backing of several influential officials, made the first move. This ambitious prince might have taken the opportunity when Aššur-etel-ilāni sent his protector Sîn‐šuma‐līšir to Babylon upon the death of Kandalānu. One conjectural scenario is as follows. With Sîn‐šuma‐līšir far away in Babylonia, presumably to be the next king of Babylon, Sîn-šarra-iškun and his supporters tried to depose Aššur-etel-ilāni. With the Assyrian heartland in chaos, Sîn‐šuma‐līšir saw his chance to grab power for himself, marched back to Assyria with his men, declared himself king, and fought his rivals, principally Sîn-šarra-iškun, for control of Assyria. His efforts, however, were in vain. Sîn-šarra-iškun gained the upper hand and forced Sîn‐šuma‐līšir to retreat south to Babylonia, where he assumed he would be safe. This would not be the case, since Nabopolassar, an influential man from Uruk with ambitions of his own, captured and executed him. This, of course, is conjectural, but one possible scenario for how events played out in Assyria in 627, especially since it is equally likely that Sîn‐šuma‐līšir rebelled against Aššur-etel-ilāni and that Sîn-šarra-iškun countered the chief eunuch's bid for the Assyrian crown only after that ambitious man had tried to remove his brother from the throne. Until new textual evidence comes to light, this matter will remain a subject of scholarly debate.

[214] A few of his inscriptions seem to imply that he was young when he came to the throne; see, for example, Ssi 10 lines 16b–19. However, he could not have been that young when he came to power since Aššur-uballiṭ II, assuming that he was indeed a son of his, must have been old enough to take over the duties of king when his father died in 612 and, therefore, Aššur-uballiṭ must have been born prior to Sîn-šarra-iškun becoming king in late 627. It is not impossible that Sîn-šarra-iškun was an older brother of Aššur-etel-ilāni.

[215] Da Riva, JNES 76 (2017) p. 82 ii 10´–16´. See Gerber, ZA 88 (1998) p. 83; and Tadmor, Studies Borger pp. 353–357. Sîn-šarra-iškun might have put an end to his rivalry with Sîn‐šuma‐līšir by forming an alliance, albeit a very short-lived one, with Nabopolassar, who, seeking power for himself, agreed to the (terms of a bilateral) treaty since it was in his own interest to have Sîn‐šuma‐līšir out of the way. Nabopolassar, a self-described "son of a nobody," appears to have come from a family that had strong Assyrian ties, with several of its members having served as high officials on behalf of Assyrian kings in Uruk. It is possible that he might have served as the governor of that Babylonian city. For details, see Jursa, RA 101 (2007) pp. 125–136. For brief biographical sketches of this Neo-Babylonian ruler, see, for example, Brinkman, RLA 9/1–2 (1998) pp. 12–16; and Da Riva, GMTR 4 pp. 2–7 §1.2.1.

Jamie Novotny

Jamie Novotny, 'Aššur-etel-ilāni and His Chief Eunuch Sîn-šuma-līšir', RINAP 5: The Royal Inscriptions of Ashurbanipal, Aššur-etel-ilāni, and Sîn-šarra-iškun, The RINAP/RINAP 5 Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, 2023 [http://oracc.org/rinap/rinap5/rinap53introduction/ashuretelilaniandsinshumalishir/]