Ashurbanipal's Death

Classical sources give an account of the final days of the Assyrian Empire, an event also documented in one cuneiform source: the so-called "Fall of Nineveh Chronicle" (see the section Chronicles below for a translation). According to the "History of Persia" written by Ctesias of Cnidus,[174] a Greek physician living at the Persian court in the late 5th century, the "last" king of Assyria, Sardanapalus — a man identified with Ashurbanipal rather than his son Sîn-šarra-iškun, the last Assyrian king to have ruled from Nineveh — committed suicide when he thought that Nineveh was about to fall to the Babylonian and Median forces laying siege to his capital. This fictional account narrates the Assyrian king's tragic death as follows:

This account, which inspired Lord Byron's tragedy Sardanapalus and Eugene Delacroix's La mort de Sardanapale,[176] appears to have conflated Ashurbanipal's death with that of his brother Šamaš-šuma-ukīn, who, according to Ashurbanipal's inscriptions, was burned alive in his palace in late 648,[177] or that of his son Sîn-šarra-iškun, who died when the Babylonians and Medes sacked Nineveh in 612.[178]

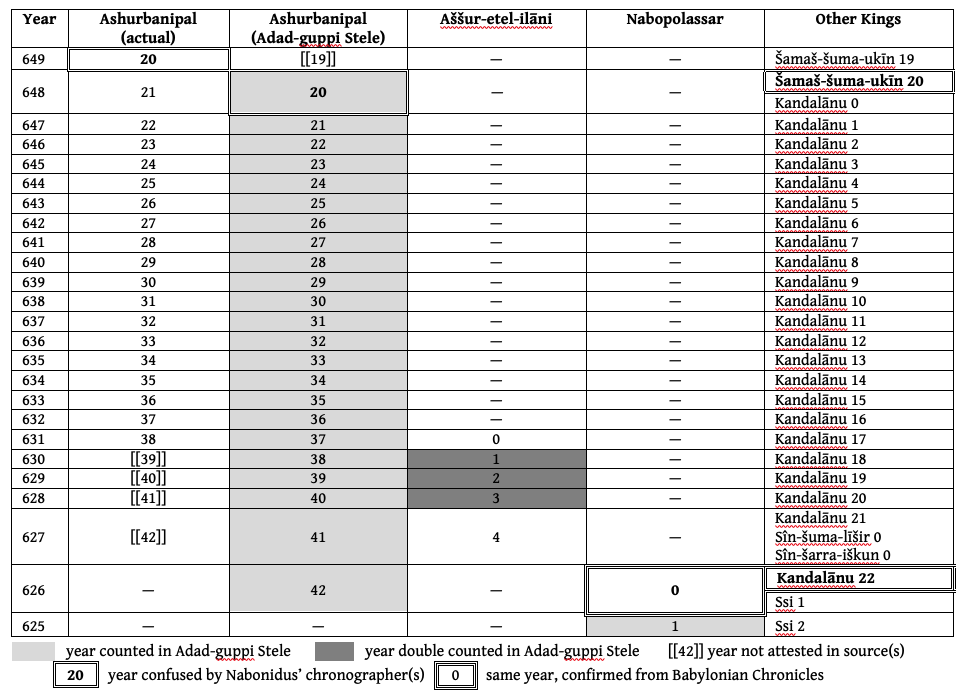

After Ashurbanipal died, he was succeeded by his son Aššur-etel-ilāni. When and how Ashurbanipal's death occurred has been a subject of debate since few sources shed light on the matter,[179] and, thus, scholars generally believe that he ruled over Assyria until 631, 630, or 627.[180] Based on contemporary (Babylonian) evidence, Ashurbanipal was king (of Assyria) until at least Simānu (III) of his 38th year (631),[181] but, according to an inscription of Nabonidus' mother Adad-guppī (Hadad-ḥappī), he reigned until his 42nd year (627).[182] At present, the "Adad-guppi Stele Inscription" is the only Akkadian source that gives a length of reign for Ashurbanipal. The relevant passages of that "pseudo-autobiographical" text, which is engraved on two round-topped monuments discovered in and near Ḫarrān, reads:

It is clear from this inscription — which was written by Nabonidus (555–539) on his mother's behalf a few years after her death in 547, perhaps during his 14th (542) or 15th (541) year as king[184] — that there is an obvious discrepancy between the age given for Adad-guppī in the text (104) and the actual number of years between Ashurbanipal's 20th year and Nabonidus' 9th year (102).[185] Much ink has been spilt on the matter, especially about the lengths of Ashurbanipal's and Aššur-etel-ilāni's reigns. Can the information presented in Adad-guppī's biographical account of her long life be reconciled with other Babylonian documents? Possibly, yes.

It is clear from other extant chronographic sources that the composer(s) of the Adad-guppi Stele Inscription had a firm grasp on the length of reigns for the Neo-Babylonian kings, starting with Nabopolassar, the first ruler of the "Neo-Babylonian Dynasty." The chronographer correctly assigns twenty-one years to Nabopolassar (625–605), forty-three years of Nebuchadnezar II (604–562), two years to Amēl-Marduk (561–560), and four years to Neriglissar (559–556).[186] Because the short reign of Lâbâši-Marduk (556), which lasted only two or three months, took place during the same year as the 4th and final year of his father Neriglissar, that short-reigned ruler is omitted from the list of rulers during whose reigns Adad-guppī lived. The reigns of the four aforementioned Babylonian rulers account for seventy of the ninety-five years of Adad-guppī's life before her son officially became king, which took place on 1-I-555 (during the Nisannu New Year's festival). The queen mother lived until 5-I-547, the 5th of Nisannu (I) of Nabonidus' 9th year.

The composer(s) of the Adad-guppi Stele Inscription, however, had less of a grasp on Assyrian history, in particular, the length of the reigns of Ashurbanipal, in whose country and during whose reign Adad-guppī was born, and his first successor Aššur-etel-ilāni.[187] Information about Assyria's last three kings — Sîn-šuma-līšir, Sîn-šarra-iškun, and Aššur-uballiṭ II — was not essential because Sîn-šuma-līšir's and Sîn-šarra-iškun's reigns began (and ended in the case of the former) in a year in which Aššur-etel-ilāni was still king[188] and the tenures of Sîn-šarra-iškun and Aššur-uballiṭ overlapped with Nabopolassar's reign. Because the requisite years were subsumed under Aššur-etel-ilāni or Nabopolassar there was no need to mention Sîn-šuma-līšir, Sîn-šarra-iškun, or Aššur-uballiṭ II in the list of rulers during whose reigns Adad-guppī lived.[189] Moreover, the same was true of Kandalānu, the king of Babylon who was placed on the throne by Ashurbanipal and ruled over Babylonia for twenty-one years,[190] since his tenure took place while Ashurbanipal and Aššur-etel-ilāni ruled Assyria.[191] The text's chronographer(s) appear not to have had concrete information about the reigns of Assyria's last kings, very likely as that information was not readily available.[192] They were, however, certain about two things: (1) there were twenty-two years between the end of the Šamaš-šuma-ukīn rebellion in 648 — as that piece of information was recorded in several Babylonian Chronicles — and the first year of Nabopolassar in 625;[193] and (2) Aššur-etel-ilāni succeeded his father as king of Assyria for a short time and that his tenure did not overlap with that of Nabopolassar, unlike his successors Sîn-šarra-iškun and Aššur-uballiṭ II. The composer(s) of the Adad-guppi Stele Inscription, who very likely did not have precise information at hand, assigned a forty-two-year reign to Ashurbanipal and a three-year reign to Aššur-etel-ilāni.[194] This timeframe — Ashurbanipal's 21st to 42nd regnal years[195] and Aššur-etel-ilāni 1st to 3rd regnal years — covered the remaining twenty-five years of the ninety-five years that Adad-guppī had lived before Nabonidus officially became the king of Babylon. In total, Nabonidus' mother is said to have lived 104 years, which is impossible as there were only 102 years from 649 (Ashurbanipal's 20th year) to 547 (Nabonidus' 9th year). Because Nabonidus' literary craftsmen were aware of the number of years that had transpired between Adad-guppī's (purported) birth and her (recorded) death, they must have known that they had assigned too many years to the life of the centenarian queen mother.

Presumably in order not to give the impression that Ashurbanipal's reign was not immediately followed by Nabopolassar's, the chronographer(s)/composer(s) included Aššur-etel-ilāni in the list of kings, even though it was abundantly clear that adding that ruler's regnal years was superfluous and that the total for Adad-guppī's lifespan would be more than she actually lived.[196] If the three double-counted years for Aššur-etel-ilāni's reign are excluded from the year count, the total is reduced to 101, which is one year shy of the needed 102 years between 649 and 547. If Nabonidus' scholars actually knew how many years had passed since Ashurbanipal's 20th regnal year, they would have been aware that there were twenty-three years between 649 and 626, not twenty-two as they record.[197] Thus, they should have assigned Ashurbanipal a forty-three-year reign, but they did not. The missing year would then bring the count back up to the required 102 years. The subtraction of three years and the miscalculation of the date of Ashurbanipal's 20th year (which is off by one year) seems a rather unlikely scenario, especially as it is needlessly complex. The double counting can easily be accounted for, but the missing year for Ashurbanipal that is then accurately accounted for cannot. There must have been a simpler, more rational explanation for how Nabonidus' chronographer(s) calculated the age of his very old mother.

Based on the extant sources currently at our disposal, Babylonian Chronicles in particular, it appears that Nabonidus' scholars wrongly identified Ashurbanipal's 20th year (649): they seem to have confused it with Šamaš-šuma-ukīn's 20th and final year (648), the milestone year that his rebellion ended, as well as a year in which the New Year's festival at Babylon did not take place.[198] There are precisely twenty-two years between the end of Šamaš-šuma-ukīn's tenure as king and the 1st year of Nabopolassar's reign, as well as between interruptions in the akītu-festival at Babylon in 648 and 626. Moreover, these years match the number of years attributed to Kandalānu by the Ptolemaic Canon and economic documents.[199] Given that the 20th year loomed large in Babylonian (and Assyrian) historical memory, since it was the year the protracted war between Ashurbanipal and Šamaš-šuma-ukīn concluded, it should not come as a surprise that more than one hundred years later Nabonidus' chronographer(s) regarded the 20th year in texts accessible to them as Ashurbanipal's, not Šamaš-šuma-ukīn's, 20th regnal year. They would not have been the only men to have confused or mixed up the dates of past events, as it is clear that there are a number of errors in extant Babylonian Chronicles. For example, the Šamaš-šuma-ukīn Chronicle wrongly states that a bed of Marduk entered Babylon in the "14th year (of Šamaš-šuma-ukīn [654])," when it should have been the "13th year (of Šamaš-šuma-ukīn [655])," since that text dates events by the regnal years of the king of Babylon. The 14th year would be correct if the year refers to Ashurbanipal's 14th regnal year (655).[200] Thus, it is not implausible for Nabonidus' scribes to have regarded Šamaš-šuma-ukīn's 20th year as Ashurbanipal's 20th year. If this was the case, does the math add up? Yes. There are 101 years between 648 ("Ashurbanipal's" 20th year; 648 = Šamaš-šuma-ukīn Year 20) and 547 (Nabonidus' 9th year) and 104 years when the double-counted three-year reign of Aššur-etel-ilāni are taken into account.[201] Moreover, the twenty-two years of Ashurbanipal during which Adad-guppī claims to lived corresponds exactly to the requisite number of years between the end of Šamaš-šuma-ukīn rebellion and the first year of Nabopolassar's reign. Thus, it seems highly probable that Nabonidus' mother was born in 648, and not in 649, as previously thought.[202]

Based on the available evidence, it appears that Ashurbanipal reigned until early 631, as evidenced from the latest Babylonian economic documents dated to his reign. Thus, his son and first successor Aššur-etel-ilāni was probably king 630–627 and his son and second successor Sîn-šarra-iškun likely ruled over Assyria 626–612.

Notes

[174] For example, see Lenfant, Ctésias de Cnide; and Rollinger in Frahm, Companion to Assyria pp. 571–572.

[175] Kuhrt, Persian Empire p. 41 no. 16 §27.

[176] For images of Ashurbanipal in later tradition, see Frahm, Studies H. and M. Tadmor pp. 37*–48*. Because nothing about Ashurbanipal's death is recorded in cuneiform sources, it has been sometimes suggested that Ashurbanipal died by fire; see Frame, Babylonia p. 155.

[177] Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 158 Asb. 7 (Prism Kh) viii 55´–61´ and p. 243 Asb. 11 (Prism A) iv 46–52. W. von Soden, (ZA 62 [1972] pp. 84–85) has suggested that an official by the name of Nabû-qātē-ṣabat threw Šamaš-šuma-ukīn into the fire; for evidence against that proposal, see Frame, Babylonia p. 154 n. 101. Ctesias' account of the death of Ashurbanipal might have mistaken the death of the Assyrian king at Nineveh with that of the king of Babylon. If that Classical description of Ashurbanipal's death was based on the death of Šamaš-šuma-ukīn, then the king of Babylon might have committed suicide. For this opinion, see Frahm, Studies H. and M. Tadmor p. 39*; and MacGinnis, Sumer 45 (1987–88) pp. 40–43. Note that Šamaš-šuma-ukīn's death is also recorded in the Amherst Papyrus 63.

[178] According to Berossos, a Hellenistic-era priest of the god Bēl (Marduk) who wrote a Greek history of Babylonia (Babyloniaca), Sarakos (Sîn-šarra-iškun) was afraid of being captured and thus committed suicide by burning down his palace around him; see Burstein, SANE 1/5 p. 26. It is possible that Berossos, who was writing long after the events of 612, confused Sîn-šarra-iškun's death with that of Ashurbanipal or more likely that of his brother Šamaš-šuma-ukīn, a king of Babylon who is known with certainty to have died in a conflagration.

[179] Assyrian chronographic sources are of no use since: (1) the Assyrian King list, the so-called "SDAS List," ends with the reign of Shalmaneser V (Gelb, JNES 13 [1954] pp. 209–230; and Grayson, RLA 6/1-2 [1980] pp. 101–115 §3.9); and (2) the latest preserved entries in the Assyrian Eponym Chronicle and Eponym Canon are respectively for the years 699 and 649 (Millard, SAAS 2 pp. 49 and 54). Babylonian chronographic texts are also of no help since Ashurbanipal is not included in Babylonian King List A (Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 29) or the Ptolemaic Canon (ibid. p. 30). The Uruk King List (ibid. p. 29) probably mentions Ashurbanipal, but states that he ruled over Babylonia jointly with his brother Šamaš-šuma-ukīn for twenty-one years (669–648), before Kandalānu was king for twenty-one years (647–627). Although Synchronistic King Lists (ibid. pp. 29–30) mention Ashurbanipal, those texts do not record the lengths of the kings' reigns. Moreover, the Babylonian Chronicles (ibid. pp. 34–36; and the present volume pp. 42–46) are not preserved for the years 647 (Ashurbanipal's 22nd year) to 628 (Kandalānu's 20th regnal year = Aššur-etel-ilāni's 3rd year as king); part of the entry for 627 is extant and his son Sîn-šarra-iškun is mentioned in the report for that year.

[180] See, for example, Naʾaman, ZA 81 (1991) pp. 243–267, especially pp. 243–255; Zawadzki, ZA 85 (1995) pp. 67–73; Beaulieu, Bagh. Mitt. 28 (1997) pp. 367–394; Gerber, ZA 88 (1998) pp. 72–93; Reade, Orientalia NS 67 (1998) pp. 255–265; Oelsner, Studies Renger pp. 643–666, especially pp. 644–645; Liebig, ZA 90 (2000) pp. 281–284; and Fuchs, Studies Oelsner pp. 25–28 and 35.

[181] Brinkman and Kennedy, JCS 35 (1983) p. 24 no. J.38. N 4016 comes from Nippur. This document is dated to 20-III-631. It is possible that Ashurbanipal could have died prior to this and news of his death had not yet reached Nippur from the Assyrian capital.

[182] Weiershäuser and Novotny, RINBE 2 p. 225 Nabonidus 2001 (Adad-guppi Stele) i 30.

[183] Weiershäuser and Novotny, RINBE 2 pp. 225–226 Nabonidus 2001 (Adad-guppi Stele) i 29–33a and ii 26–29a.

[184] According to the Nabonidus Chronicle (Weiershäuser and Novotny, RINBE 2 p. 26) ii 13–15a, Adad-guppī died on 5-I-547 (= April 6th 547) in the city Dūr-karašu, which was on the Euphrates River, upstream of Sippar. On the date of composition of the Adad-guppi Stele, see Beaulieu, Nabonidus p. 68 n. 1; and Schaudig, Inschriften Nabonids p. 501.

[185] The composer(s) of the text used inclusive, rather than exclusive, dating for Adad-guppī's age, that is, Nabonidus Year 9 is included in the counting of years, even though the king's mother only lived five days into her son's 9th regnal year.

[186] These dates are more or less confirmed by the Uruk King List and the Ptolemaic Canon (Weiershäuser and Novotny, RINBE 2 p. 24). Note that the Uruk King List records that Neriglissar ruled for three years and eight months and that his young son Lâbâši-Marduk was king for only three months. Berossus assigns nine months to the reign Lâbâši-Marduk. Based on economic documents, a reign of two or three months is likely for Neriglissar's young son, but not the nine stated by Berossus, since his reign is attested only for the months Nisannu (I), Ayyāru (II), and Simānu (III) of his accession year; see Beaulieu, Nabonidus pp. 86–87. Based on date formulae of business documents, the Uruk King List appears to give too long a reign to Neriglissar, who appears to have died a few days into his 4th regnal year; the latest presently-attested document dated by his reign was written at Uruk on 6-I (YBC 3433; Parker and Dubberstein, Babylonian Chronology p. 12). Despite the fact that Neriglissar was king for only a short time after the start of his 4th regnal year, he is credited with a four-year reign by the composer(s) of the Adad-guppi Stele Inscription. That year (556) was regarded as Neriglissar Year 4, Lâbâši-Marduk Year 0, and Nabonidus Year 0. For a recent study on the date of Nabonidus' accession to the throne, see Frame, Studies Rochberg pp. 287–295.

[187] Adad-guppī was very likely born in (or at least near) Ḫarrān. W. Mayer (Studies Römer pp. 250–256) has suggested that Adad-guppī might have been a daughter of the Assyrian prince Aššur-etel-šamê-erṣeti-muballissu (Pempe, PNA 1/1 pp. 184–185; Novotny and Singletary, Studies Parpola pp. 170–171) and, therefore, a granddaughter of Esarhaddon, but there is no extant textual evidence to support this proposal.

In scholarly literature, Nabonidus' mother is sometimes referred to as a priestess of the god Sîn of Ḫarrān on account of the devotion she claims to have given to the moon-god in the stele inscription written in her name. However, this need not be the case, since it is equally as plausible that Adad-guppī was simply a pious, upper class lay-woman. The piety expressed in her pseudo-autobiographical account of her life does not necessarily have to be interpreted as cultic obligations of a priestess. See the discussions in Dhorme, RB 5 (1908) p. 131; Garelli, Dictionnaire de la Bible 6 (1960) p. 274; Funck, Altertum 34 (1988) p. 53; W. Mayer, Studies Römer (1998) pp. 253–256; and Jursa, Die Babylonier p. 37. Note that many years ago B. Landsberger (Studies Edhem p. 149) already argued against the idea of Adad-guppi being an ēntu-priestess of the moon-god at Ḫarrān and that P. Michalowski (Studies Stolper p. 207) believed that this proposal is "an unsubstantiated modern rumor."

[188] Sîn-šuma-līšir's months-long reign (= his accession year) took place during the final year of Aššur-etel-ilāni's reign and at the same time as the accession year of Sîn-šarra-iškun. It also took place during the final year that Kandalānu, the king of Babylon, was alive (his 21st regnal year).

[189] With the exception of Sîn-šarra-iškun's accession year, which was the year before Nabopolassar became king, the entire reign of Assyria's penultimate king overlaps with the tenure of the founder of the Neo-Babylonian Empire. The entire duration of Aššur-uballiṭ II's reign also took place while Nabopolassar was king of Babylon. Moreover, Sîn-šarra-iškun Year 1 took place during the posthumous Kandalānu Year 22 (see the note immediately below).

[190] The Uruk King List (Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 29) credits Kandalānu with a twenty-one-year reign, but the Ptolemaic Canon (ibid. p. 30) states that he was king for twenty-two years. The length of Kandalānu's reign is broken away in Babylonian King List A (ibid. p. 29), but it might have been twenty-one years since that text also appears to list Sîn-šuma-līšir (reading uncertain) as a king of Babylon. The attribution of twenty-two years to Kandalānu comes from economic documents that are posthumously dated to his 22nd regnal year; see Brinkman and Kennedy, JCS 35 (1983) p. 49 no. L 163, which comes from Babylon and is dated to 2-VIII-626, which was twenty-four days before Nabopolassar became king (26-VIII-626). Kandalānu died early in his 21st regnal year, perhaps in late Ayyāru (II) or early Simānu (III). The latest economic document not posthumously dated to his reign was written on 8-III-627 (ibid. p. 49 no. L.159) and the earliest text posthumously dated to his tenure is 1-VIII-627 (ibid. p. 49 no. L.160). Because no one (Sîn-šarra-iškun or Nabopolassar) was in a position to take the hand of Marduk during the akītu-festival at Babylon on 1-I-626, the New Year's festival did not take place, as the Akītu Chronicle records (see the section Chronicles below) and nobody was officially crowned as the king of Babylon; thus, some economic documents continued to be dated by Kandalānu's reign. Rather than recording a one-year kingless period, the Ptolemaic Canon gives an extra year of reign to Kandalānu. Note that this text also assigns an extra year to Esarhaddon, attributing to him a thirteen-year-long reign. The additional year covers Šamaš-šuma-ukīn's accession year (668).

[191] Adad-guppī was probably living in Assyria until Nabopolassar captured and destroyed Ḫarrān in 610 and, thus, from her perspective (as composed by Nabonidus' scribes after her death), Ashurbanipal and Aššur-etel-ilāni were kings before Nabopolassar came to power. Therefore, one would not expect the queen mother to regard Kandalānu, or even Šamaš-šuma-ukīn, as a king during whose reign she had lived since they were Babylonian kings who were contemporaries of Ashurbanipal and his son Aššur-etel-ilāni.

[192] See n. 179 above.

[193] Based on extant chronographic sources, the end of the Šamaš-šuma-ukīn rebellion would very likely have been recorded for that king of Babylon's 20th regnal year (648) in the Esarhaddon Chronicle and the Šamaš-šuma-ukīn Chronicle; see Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 pp. 34–35. The Akītu Chronicle (lines 23–27) records that the New Year's Festival did not take place during the 20th year (of Šamaš-šuma-ukīn), the last year of the Brothers' War, as well as in Nabopolassar's accession year (626 = posthumous Kandalānu Year 22). The twenty-two-year period in question corresponds to the reign of Kandalānu according to the Ptolemaic Canon and economic documents dated to that king's tenure (627–626) or to the twenty-one-year period for Kandalānu's reign (647–627) and the joint one-year reign for Sîn-šuma-līšir and Sîn-šarra-iškun (626), which overlapped with Nabopolassar's accession year, according to the Uruk King List and probably also Babylonian King List A (ibid. p. 29). Posthumous Kandalānu Year 22 is recorded as "for one (entire) year, there was no king in the land (Akkad)" in lines 14–15a of the Chronicle Concerning the Early Years of Nabopolassar (see the section Chronicles below). From surviving Babylonian Chronicles and King Lists, Nabonidus' scribes were clearly aware of the number of years between the end of Ashurbanipal's war with Šamaš-šuma-ukīn and the accession of Nabopolassar. Presumably, the missing entries in the Babylonian Chronicle would have been dated by Kandalānu's regnal years.

[194] Information about Aššur-etel-ilāni's 4th year as king appears to have gone unnoticed by the composer(s) of the Adad-guppi Stele Inscription. This is not surprising as Babylonian business documents dated to his reign come only from Nippur and only one is known for his 4th and final year as king (Brinkman and Kennedy, JCS 35 [1983] p. 53 no. M12). Four texts, however, are dated by his 3rd year; see ibid. p. 53 nos. M8–M11. Because there are so few presently-attested dated documents for the fourth year of Aššur-etel-ilāni's reign and since 627 was a chaotic year, with four kings by which to date business transactions (Kandalānu, Aššur-etel-ilāni, Sîn-šuma-līšir, and Sîn-šarra-iškun), it is not surprising that this Assyrian king is credited by Nabonidus' scribes as having ruled for only three years.

[195] Based on the information provided about Ashurbanipal's length of reign in the Adad-guppi Stele Inscription, some scholars (especially S. Zawadzki [Fall of Assyria pp. 57–63]) have suggested that Ashurbanipal and Kandalānu were one and the same person, but this seems unlikely, as already pointed out by J.A. Brinkman (for example, CAH2 3/2 pp. 60–62) and G. Frame (Babylonia pp. 191–213, especially 193–195, and 296–306).

[196] This is evident from the fact that Nabonidus' scholars were aware that there were only twenty-two years between the end of the Šamaš-šuma-ukīn rebellion and the 1st regnal year of Nabopolassar. Thus, any regnal years assigned to Aššur-etel-ilāni would have been regarded as a double count since those years were already included in the regnal count for Ashurbanipal.

[197] The composer(s) added twenty-two years to the 20th regnal year of Ashurbanipal to arrive at a total of forty-two years. The math, however, is off by one year when one counts from Ashurbanipal's actual 20th year as king. It is unclear, however, whether that year would have been 648 or 626.

[198] The Akītu Chronicle line 23 (Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 36) records the following for the 20th year (of Šamaš-šuma-ukīn's): "The twentieth year (648): The god Nabû did not go (and) the god Bēl did not come out." Presumably other chronicles would have noted the same information and given additional details about the end of the rebellion.

[199] See n. 190 above.

[200] On this confusion and at least one other error in the Babylonian Chronicle, see the discussion in n. 126 above.

[201] If one counts the number of months from 648 to 547, then Adad-guppīʾ would have lived to 104 years of age since there were thirty-six (or possibly thirty-seven) intercalary months during Nabonidus' mother's long life, which is the equivalent of three years. There was an Intercalary Ulūlu (VI₂) in the years 643, 640, 629, 621, 616, 611, 607, 603, 600, 598, 596, 584, 574, 564; and an Intercalary Addaru (XII₂) in the years 646, 638, 635, 624, 619, 614, 606, 594, 591, 588, 582, 579, 577, 572, 569, 563, 560, 557, 555, 553, and 550. In addition, intercalary months were expected in 632 and between 629 and 624 (possibly in 625). The count would be one month more if Adad-guppīʾ were to have been born in 649, rather than in 648, since that year had an Intercalary Addaru (XII₂).

[202] This would mean that Adad-guppīʾ was 101, not 102, years old.

Jamie Novotny

Jamie Novotny, 'Ashurbanipal's Death', RINAP 5: The Royal Inscriptions of Ashurbanipal, Aššur-etel-ilāni, and Sîn-šarra-iškun, The RINAP/RINAP 5 Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, 2023 [http://oracc.org/rinap/rinap5/rinap53introduction/ashurbanipalsdeath/]