Ḫarrān

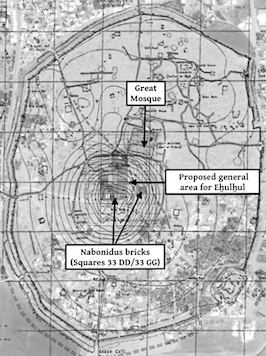

Figure 11. Satellite image of Ḫarrān overlaid with a general plan of the city (Lloyd and Brice, AnSt 1 [1951] p. 85 fig. 3) and the excavated areas (Yardımcı, Studies Palmieri p. 441 fig. 4).

Long before the Sargonid period (721–609), Ḫarrān (modern Harran), its principal temple Eḫulḫul ("House Which Gives Joy"), its tutelary deities (the moon-god Sîn, Nikkal, Nusku, and Sadarnunna), and its largely Aramaean population enjoyed a privileged position within the Assyrian Empire, especially after Sargon II became king.[100] Of Ashurbanipal's numerous building activities, rebuilding and expanding the Eḫulḫul temple complex took pride of place, as evidenced from the numerous inscriptions of his recording work at Ḫarrān.[101] Unlike his work at Arbela, Aššur, and Babylon — which mostly consisted of projects of his father that he merely put the finishing touches on since construction in those cities had largely been completed while Esarhaddon was alive — large-scale building in this cult center of the moon-god was both initiated and completed during Ashurbanipal's reign; the work appears to have (mostly) taken place during his first decade as king (668–659).[102] Esarhaddon might have been planning to rebuild or renovate Eḫulḫul,[103] but he died before any work was carried out, at least this is what some of Ashurbanipal's inscriptions might indirectly suggest.[104]

Before the work began, divine approval was obtained from Ḫarrān's tutelary deities (Sîn and Nusku). After receiving a positive response to a haruspical query, workmen removed the existing mudbrick structure of the temple, which is said to have been old and dilapidated. During the removal process, objects inscribed by earlier builders were discovered; the only past king named was king Shalmaneser III (858–824).[105] The old structure was completely removed, thereby exposing its (stone) foundations. After specialists deemed the foundations, those laid when Shalmaneser III was king, suitable for reuse,[106] the new brick superstructure was raised to a height of thirty courses of bricks (ca. 3.3–3.6 m). While Ashurbanipal's workmen were removing the former Eḫulḫul temple and rebuilding its new superstructure, the temple complex was greatly expanded, incorporating an additional plot of land measuring ca. 175 × 32.5 m, which was then raised by 130 courses of bricks (ca. 11.7–15.6 m, depending on the thickness of the bricks used) in order to bring the newly-incorporated area to the same height as the foundations of Sîn's temple. Massive ashlar blocks hewn from the mountains (ešqī abnī šadî danni) were laid as the foundations for the new part of the temple complex, which was very likely a larger temple for the god Nusku. The new and improved Emelamana ("House of the Radiance of Heaven"), whose superstructure is presumed to have been also raised to a height of thirty courses of bricks, might have been constructed as a twin/mirror image of Eḫulḫul and the two temples might have been physically attached to one another.[107]

Both Eḫulḫul and Emelamana were roofed with cedar beams imported from the Levant, specifically from Mount Lebanon and Mount Sirāra and had metal-banded doors hung in their principal gateways.[108] Ashurbanipal had the interior rooms, at least the ante-cellas (bīt papāḫi) and cellas (atmanu) of Sîn and Nusku, lavishly decorated and had metal(-plated) and inscribed apotropaic figures placed in important gateways. The main cult rooms of Eḫulḫul were decorated with seventy talents of shiny zaḫalû-metal. It is not known exactly what types of decorative objects were displayed in that room, but the massive amount of metal used to make this room shine brightly was almost certainly acquired during Ashurbanipal's second Egyptian campaign (664), principally from two obelisks that are reported to have been "cast with shiny zaḫalû-metal" and to have weighed 2,500 talents each.[109] In Sîn's ante-cella and cella, three pairs of apotropaic figures were stationed to protect that part of the temple: wild bulls (rīmu), long-haired heroes (laḫmu), and lion-headed eagles (anzû). In Nusku's new ante-cella, Ashurbanipal had at least one pair of lion-headed eagles fashioned as gateway guardians. Numerous other metal and metal-plated objects were created for the divine residents of the expanded Eḫulḫul temple complex, including a pair of gold-plated carrying poles for Sîn's consort Nikkal and a reddish-gold-plated archway (sillu) or awning (ṣillu) for Emelamana.[110]

When the temples were completed, Ashurbanipal had Ḫarrān's gods and goddesses brought into the double Eḫulḫul-Emelamana temple during a boisterous celebration. Despite the fact Ashurbanipal claims to have personally taken the moon-god by the hand, it is unknown whether or not Ashurbanipal was physically present at Ḫarrān for Sîn's return to Eḫulḫul. Since the completion of the moon-god's temple appears to have been a major accomplishment, it is likely that he personally attended the ceremonies. If he was unable to attend, then his kuzippu-garments[111] or his younger brother Aššur-etel-šamê-erṣeti-muballissu, who was then a šešgallu-priest of Sîn,[112] might have stood in for him. Apart from the construction of his own palace at Nineveh, the completion of Eḫulḫul and its mirror image Emelamana was Ashurbanipal's greatest building accomplishment, one that would be remembered long after his death.[113]

During his third decade as king (ca. 644–642), Ashurbanipal had the akītu-house of Sîn rebuilt and decorated with zaḫalû-metal.[114] Unfortunately, no further details have survived about this New Year's temple, which was apparently located inside the city.[115]

Notes

[100] This section is largely an overview of the recently-published Novotny, Studia Chaburensia 8 pp. 73–94. That paper is a summary of parts of Novotny, Eḫulḫul (an unpublished University of Toronto dissertation). An open-access PDF is downloadable from Harrassowitz (https://www.harrassowitz-verlag.de/title_6624.ahtml; last accessed April 11, 2022). For a study of the moon-god during the Neo-Assyrian period, see Hätinen, dubsar 20, especially pp. 384–415 for that deity's cult at Ḫarrān.

[101] Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 58 no. 3 (Prism B) i 16–23, p. 83 no. 4 (Prism D) i 14–19a, p. 104 no. 5 (Prism I) ii 2´–18´, pp. 114–115 no. 6 (Prism C) i 65´–93´, p. 140 no. 7 (Prism Kh) i 39´–65´, p. 167 no. 8 (Prism G) i 1´–2´a), p. 217 no. 10 (Prism T) ii 29–iii 14, and pp. 303–304 no. 23 (IIT) lines 64–72; and, in this volume, no. 190 i 1–15, no. 207 (LET) rev. 43–69, no. 208 lines 23–rev.1, no. 209 lines 19–24, no. 211 lines 24–27, no. 212 lines 13´–18´, no. 214 lines 24–29, no. 215 (Edition L) v 14–20, no. 218 lines 1´–9´, and no. 232 ii 1–7. A report about the rebuilding of Eḫulḫul might be preserved in text no. 116 i 9´b–15´ and text no. 222 lines 14b–15; see the commentary and on-pages notes of text no. 116 for details.

[102] It is fairly certain that the work on the main temple complex was completed before V-8-648, but how much earlier than that is unclear. Based on a description of the construction of Sîn's temple in text no. 207 (LET), which was composed sometime after ca. 664, it is tentatively proposed here that work on the Eḫulḫul complex, specifically the completion of the temple of the god Nusku, Emelamana ("House of the Radiance of Heaven"), was completed ca. 659, although this cannot yet be proven with certainty. The rebuilding of the akītu-house was undertaken during Ashurbanipal's third decade as king, ca. 644–642.

[103] For the extent of Esarhaddon's activities at Ḫarrān, see Novotny, Studia Chaburensia 8 p. 76. It is highly doubtful that Esarhaddon rebuilt Eḫulḫul in its entirety.

[104] In several inscriptions, Ashurbanipal claims that he was destined to be the king who rebuilt this temple of the moon-god. For example, text no. 10 (Prism T) ii 29–43 (Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 217): "Before my father was born (and) my birth-mother was created in her mother's wo[mb], the god Sîn, who created me to be king, named me to (re)build Eḫulḫul, saying: 'Ashurbanipal will (re)b[uild] that temple [and] make me dwell therein upon [an e]ternal [dais.' The word of the god S]în, which [he had spoken] in distant days, [he n]ow reve[aled to the peo]ple of a later generation. He allowed [the temple of the god Sîn — which] Shalmaneser (III), [son of Ashurnasirpal (II)], a king of the past (who had come) before [m]e, [had b]ui[lt] — to become old and he entrusted (its renovation) to me." As Ashurbanipal does not make this claim for any other building project, it can be interpreted here that Esarhaddon had been planning to rebuild/renovate Ḫarrān's principal temple, but he did not do so before his death. Therefore, Ashurbanipal's imagemakers took the opportunity to highlight the fact that it was Ashurbanipal, not his father, who undertook that project.

[105] Presumably other kings worked on the temple, but since it was traditional to name one and only one previous builder in a description report, certainly Shalmaneser III was regarded as the most famous of the earlier kings who had worked on Eḫulḫul. For a study of the selective nature of Assyrian building reports, see Novotny, JCS 66 (2014) pp. 109–112; and Novotny in Yamada, SAAS 28 pp. 253–267.

[106] One inscription of the Neo-Babylonian king Nabonidus (555–539) states that Ashurbanipal had Sîn's temple built anew directly on top of the foundations that Shalmaneser III had laid in the ninth century. See Weiershäuser and Novotny, RINBE 2 p. 148 Nabonidus 28 (Eḫulḫul Cylinder) i 41–ii 5a.

[107] B. Pongratz-Leisten (Studies Boehmer p. 554) was the first person to suggest that Emelamana was a twin of Eḫulḫul. This proposal is accepted here, as well as in Novotny, Eḫulḫul pp. 78–79 and 81–82. Of course, since Eḫulḫul and Emelamana have not yet been discovered, this suggestion must remain conjectural. Note that excavations of the ruins of Ḫarrān in the 1950s, 1980s, and 1990s did not unearth a single inscribed Assyrian object, nor did these scientific investigations find the remains of Eḫulḫul, apart from numerous bricks and half-bricks of Nabonidus, none of which were found in situ. It is possible that Eḫulḫul was located near the edge of the city's citadel, possibly in the northeastern quadrant. Given the (oral and) written tradition that the Paradise Mosque was constructed on top of the temple of the moon-god, and the fact that numerous stamped bricks of the Neo-Babylonian king Nabonidus were found in trenches 35 DD and 36 GG and that steles of that king and his mother were reused in the structure of the mosque, it is not impossible that Eḫulḫul was located in the northeastern part of the mound (höyük).

[108] Several kings of the Sea Coast aided in the acquisition and transport of the timber. Although the rulers who assisted are not named, most likely some of them were the same individuals who supplied his father Esarhaddon with timber and stone during the construction of a wing of the armory at Nineveh and who aided Ashurbanipal's troops with re-establishing Assyrian control over Egypt; twenty-two rulers are reported to have reaffirmed their loyalty to Assyria in 667. Although it is not known which kings of the Sea Coast contributed to the construction of Eḫulḫul, it is possible that Baʾalu of Tyre, Milki-ašapa of Byblos, Iakīn-Lû (Ikkilû) of Arwad, and Abī-Baʾal of Samsimurruna provided timber since Mount Lebanon and Mount Sirāra were in their spheres of influence.

[109] The two obelisks were removed from a temple at Thebes (possibly the Amun temple at Karnak). Some scholars have suggested that the (seven-meter-tall) obelisks were solid metal and date to the reign of Tuthmosis III (1504–1450). For this opinion, see, for example, Onasch, ÄAT 27/1 p. 158. According to M.A. Powell (RLA 7/7–8 [1990] p. 510 §V.6), one talent was approximately thirty kilograms (= sixty minas). Thus, each obelisk might have weighed about 75,000 kg (165,346 lbs) and, therefore, the pair might have yielded around 150,000 kg (330,693 lbs) of zaḫalû-metal. At least seventy talents (2,100 kg/4630 lbs) of that silver alloy was used to decorate Sîn's cella.

[110] Most of the building reports of the Emelamana display inscription are badly damaged and, thus, it is uncertain what metal(-plated) objects Ashurbanipal had commissioned for Nusku in his new temple at Ḫarrān.

[111] If Ashurbanipal sent his kuzippu-garments to stand in for him, then the kalû-priest Urdu-Ea or his son Nabû-zēru-iddina might have attended the ceremonies commemorating the completion of Eḫulḫul. For the importance of kuzippu-garments of the king in rituals, see, for example, Pongratz-Leisten in Parpola and Whiting, Assyria 1995 pp. 247–248.

[112] The installation of Aššur-etel-šamê-erṣeti-muballissu as šešgallu-priest of Sîn at Ḫarrān was planned by Esarhaddon, but carried out by Ashurbanipal at the very beginning of his reign. See text no. 185 (L3) lines 10–13.

[113] Ashurbanipal is named as a previous builder in an inscription of Nabonidus (Weiershäuser and Novotny, RINBE 2 p. 148 Nabonidus 28 [Eḫulḫul Cylinder] i 41–ii 5a).

[114] Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 304 no. 23 (IIT) lines 67b–68a; and, in this volume, no. 215 (Edition L) v 14–20 and vi 10–11 and text no. 216 (building report completely missing and subscript badly damaged).

[115] The exact position of the akītu-house is not indicated and it is unknown if this festival temple was located inside the Eḫulḫul complex or in another district of the city, perhaps in the lower town, near one of the city gates, but still inside the city walls. It is not impossible that it was located at or near the Deir Kadhi, which is at the Gate of the Inn of the Olives.

Jamie Novotny

Jamie Novotny, 'Ḫarrān', RINAP 5: The Royal Inscriptions of Ashurbanipal, Aššur-etel-ilāni, and Sîn-šarra-iškun, The RINAP/RINAP 5 Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, 2022 [http://oracc.org/rinap/rinap5/rinap52introduction/buildingactivitiesinassyria/harran/]