Clay Tablets

Of all of the known objects inscribed with the inscriptions of Ashurbanipal, those written on clay tablets (text nos. 72–240) are in some ways the most difficult to assess. Specifically, what were the immediate circumstances that led to them being written on this versatile medium? Were they intended to be drafts of texts written on other media? Were they intended to be archival copies or a record of texts deposited or displayed in palaces or temples? Were they scribal training exercises? Or did they have some other purpose? Given the fragmentary state of preservation of most of the known tablets with inscriptions of Ashurbanipal, these are not always easy questions to answer; in a few instances, however, it is, especially if the tablet has a(n intact) subscript (scribal note) preserved on it. The size, shape, and format of the tablets vary, just as they do with those inscribed with texts of Esarhaddon and Sennacherib.[16] The following types are known: (1) tall, single-column tablets (for example, text nos. 186, 197, 207, and 227–228); (2) short, wide single-column tablets (for example, text nos. 200 [exs. 1–2], 208, and 224); (3) uʾiltu-tablets (for example, text nos. 185 and 155 [ex. 1]);[17] and (4) multi-column tablets, with two (for example, text nos. 79, 86, 94, 161, 190, and 220) or three (for example, text nos. 91–92, 194, and 215) columns per side.

As is to be expected from the high number of tablets/fragments, there is great variation in the content of the inscriptions. The 169 texts edited in this volume, as mentioned above, fall into six broad categories: (1) building inscriptions, (2) annalistic texts, (3) summary inscriptions, (4) dedicatory inscriptions (sometimes referred to as display inscriptions), (5) collections of epigraphs, and (6) letters addressed to gods (usually to the Assyrian national god Aššur). Of the six types, annalistic texts and dedicatory inscriptions are the most common, whereas letters to gods and building inscriptions are the least frequently attested. Of course, there are texts that fall outside of these general classifications; for example, text no. 185 (K 891 [L3]) — a Ludlul-bēl-nēmeqi-style composition in which Ashurbanipal complains to an unnamed god about ill health and emotional distress despite the fact that he had performed a multitude of pious deeds — and text no. 186 (K 2867+ [Large Hunting Inscription]) — an inscription recording a lion hunting expedition that Ashurbanipal undertook with several refugee Elamite princes.[18] It is clear that some inscriptions were intended to be written on stone steles erected and displayed in prominent, public locations or in (relatively) secluded spots, for example, inside temples or shrines; it is possible that some texts were intended to be carved on difficult-to-access rock faces, despite the fact that no such inscription can be attributed to Ashurbanipal with absolute certainty. These texts, which are sometimes referred to as display inscriptions, are easily identifiable when the beginning and/or end of the text are/is sufficiently preserved. When those passages are missing or not sufficiently preserved, display inscriptions can be mistakenly identified as building inscriptions, annalistic texts, or summary inscriptions. The best known example of an Ashurbanipal display inscription is text no. 220 (K 2694+ [L4]; also known as the "School Days Inscription") — an inscription not only recording Ashurbanipal's education in the scribal arts and his training as heir designate, but also the return of the statues of Babylon's tutelary deities and the installation of Šamaš-šuma-ukīn as the king of Babylon — which, according to its concluding formula, was written on a stele (presumably placed inside the god Marduk's temple Esagil, located in the Eridu district of Babylon).

Of course, these modern, scholarly categorizations are not necessarily mutually exclusive, especially in the case of many/most dedicatory inscriptions, which can also be regarded as display inscriptions. For example, text no. 208 (K 8759+), an inscription dedicated to the moon-god Sîn, was written on the metal plating of lion-headed eagles (anzû) stationed in a gateway of the ante-cella of the Eḫulḫul temple at Ḫarrān. Some texts, like text no. 227 (K 2631+ [Nergal-Laṣ Inscription]), can encompass three different modern classifications. That inscription — which was written on objects displayed in Emeslam, the temple of the god Nergal at Cutha — can be classified as a dedicatory inscription, a summary inscription, and a display inscription since it was addressed to the king of the netherworld, intended to be displayed prominently in his temple, and since it summarized some of Ashurbanipal's military campaigns, especially those in Elam. Given the fragmentary state of preservation of nearly all of Ashurbanipal's inscriptions written on clay tablets, it is not yet possible to classify the texts with one hundred percent accuracy, especially as many texts encompass more than one modern category.

Figure 1. An example of an uʾiltu-tablet: K 891 (text no. 185). © Trustees of the British Museum.

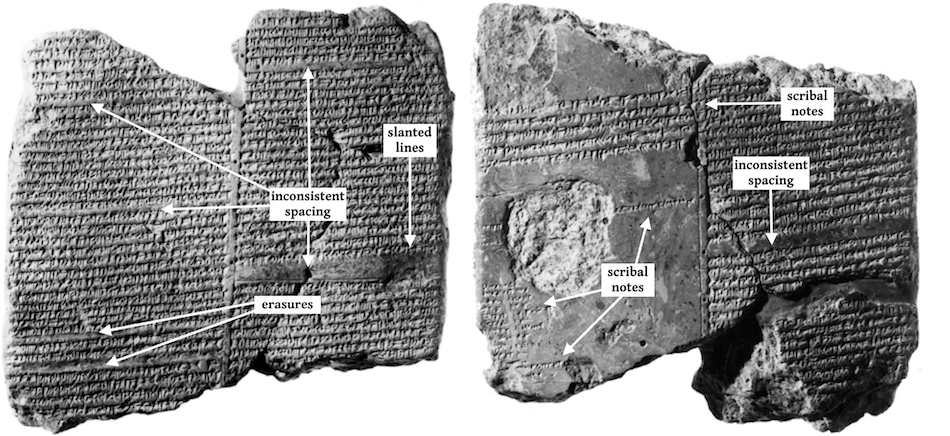

Figure 2. Example of a draft: K 2694+ (text no. 220 [L4]). © Trustees of the British Museum.

As mentioned above, the function/purpose of the tablets is not always clear. The contents of some texts, especially those written on uʾiltu-tablets (see Fig. 1 above) appear to have been drafts of inscriptions that were to be written on other media, including sculpted wall slabs or cult utensils (such a reddish-gold knife [makkas ḫurāṣi ruššî]). The crudely-made nature of some of the tablets (for example, text no. 155 ex. 1 [K 1364]) is a key piece of evidence that some texts of Ashurbanipal written on clay tablets were first or early drafts of inscriptions. Other, clear-cut pieces of evidence that texts were still in the drafting phase are: (1) scribal notations, (2) sizable erasures (more than just a single sign), (3) (numerous) errors, (4) inconsistency in writing out the text (for example, irregularity in size, orientation, and spacing of cuneiform signs and lines of text); and (5) blank spaces for information to be added at a later date (as is often the case for the epigraph collection tablets). Some tablets, like K 3065 (text no. 190), display two of these marks of a draft, while other tablets, like K 2694+ (text no. 220 [L4] in Figure 2 above) show several more. With regard to the former, the scribe crudely erased three and a half lines of text; it is unclear why he did so since the erased contents are expected based on numerous parallels. As for the latter, there is little doubt that tablet preserves an early draft of an inscription that was ultimately to have been engraved on a stele displayed in Esagil, the temple of the god Marduk in Babylon. That tablet has numerous errors and scribal notations, and several full line erasures, in addition to being written inconsistently on the tablet (variable size of signs and spaces between lines, lines of text being written at an angle rather than horizontally, and blank spaces between texts and horizontal rulings). The most notable feature of this draft is numerous scribal notations at the bottom of col. iv and in the margin between cols. iii and iv. Apparently, the scribe did not correctly arrange the order of the procession of the participants and divine objects so he noted the correct (historically accurate or ideologically appropriate) information (perhaps at the request of the king himself or on the advice of the chief scribe) in two places, (1) in a list at the bottom of col. iv and (2) as numbers in the margin between cols. iii and iv.[19] Thus, the originally-inscribed text, with the notes on how to correct the order of the lines of text (indicated with superscript numbers), read as follows:

This passage would have appeared on the carved stele, based on the rearrangement information provided by the scribe in the space between cols. iii and iv, as follows:

Figure 3. Reverse of K 2694+ (text no. 220 [L4]) with annotations about the scribal notes and their order of execution. © Trustees of the British Museum.

The order of Marduk's processional boat Maumuša (which appears to have been written in one of the now-missing lines at the beginning of col. iii) and Šamaš-šuma-ukīn required adjustment. The soon-to-be-installed king of Babylon was to immediately follow the king of Assyria, rather than be separated from him by priests, musicians, and singers, and the ceremonial, divine boat was to follow all of the non-divine participants.[20] Since the stele mentioned on K 2694+ has not been discovered, it is unknown whether or not the draft of this inscription intended for Babylon was approved by Ashurbanipal himself (or by his chief scribe, who may have vetted compositions before they were presented to the king). The text written on K 2867+ (text no. 186 [Large Hunting Inscription] ex. 1) is also a draft, which is clear from a multi-line scribal note (Text C) written over an erasure (Text A), but the text written on it is not sufficiently preserved to know the intended venue and medium of the inscription itself. Presumably numerous drafts were not approved to be used on clay, stone, or metal objects deposited or displayed in temples, royal residences, walls, or open-air (public) venues. Given the lack of evidence, we can only speculate on this matter. It is noteworthy that these tablets containing drafts have survived; they appear to have been archived rather than destroyed.

For the majority of the tablets with Ashurbanipal inscriptions, it is not clear if they were archival copies of texts on objects officially commissioned by the king or whether they were (early or final) drafts that were archived after the objects for which those texts were intended were inscribed. Subscripts (Abschriftvermerke) preserved on some of these tablets are useful in that they provide information about the location and sometimes the object upon which the text was to be written. Unfortunately, most of the subscripts are either completely destroyed (text nos. 94–95, 113?, 189?, 190, 198?, 200?, 212, 222?, and 227?) or are poorly preserved (text nos. 73, 142, 156?, 162, 201, 203, 206, 208, 210–211, 213–216, and 236). Some subscripts are fully or sufficiently intact (text nos. 79, 161, 172, 176, 178, 180, 195–196, 207 ex. 3, 209, 223–224, 225 ex. 3, and 229). Subscripts of archival copies (or drafts) of inscriptions (annalistic texts and building inscriptions) that were written on clay prisms or cylinders deposited in the mud-brick structure of buildings (akītu-houses, palaces, and temples) generally had the format "inscribed object (mušarû) for the temple of the god Nergal that (is inside) Cutha" (K 3079+ [text no. 229] rev. ii´ 1´–2´); see also K 2664+ (text no. 215) vi 10–11, which has "[an inscribed obj]ect ([muš]arû) fo[r the akītu-house of the god S]în [that is inside the city Ḫarr]ān." Texts that were engraved on the metal-plating of objects displayed in temples in palaces, including apotropaic gateway guardians (like human-headed eagles [anzû]) and cultic utensils (for example, a basket [masabbu] or a knife [makkasu]), generally were formulated a bit differently. These subscripts began with the words ša ina muḫḫi (lit. "that which is upon"), or anniʾu ša (ina) muḫḫi (lit. "this is that which is upon"), and ended with the relevant information about the inscribed object upon which the text was written. Some examples are: K 2642+ (text no. 173) iv 10´–11´ and K 4457+ (text no. 178) rev. 23–24 have "[that which is (written) u]pon the walls of the House of Succession, of the south wing" (conflated translation); Bu 89-4-26,209 (text no. 209) rev. 22 has "[t]his is what is (written) upon the poles of the goddess Ningal"; and K 2813+ (text no. 211) rev. 20 has "[that which is (written) u]pon the ... of Emelamana, the temple of the god Nusku o[f the city Ḫarrān]." In a few instances, the scribe also indicated the length of the text. For example, Sm 254 (text no. 201) was at least forty-one lines long, K 1609+ (text no. 203) had thirty lines of text, K 120B+ (text no. 224) was fifty lines long, and 80-7-19,333 (text no. 225 ex. 3) had fifty-five lines of text.[21]

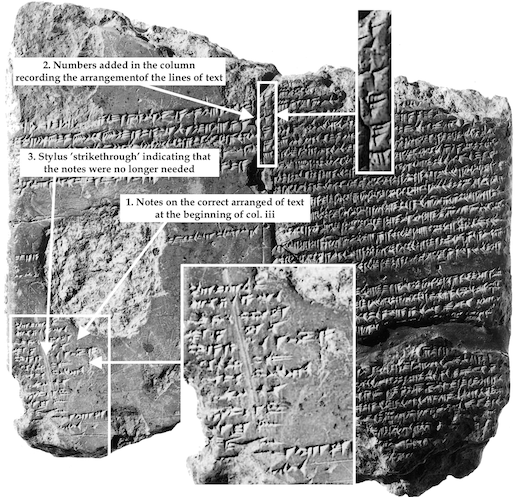

There are a few subscripts that fall outside of the aforementioned Ashurbanipal subscript formats. These appear on text nos. 79, 161, 195, and 223. The end note written on K 3408 (text no. 195) reads: "Letter of Ashu[rbanipal ...] to (the god) Aššur, who resides in E[ḫursaggalkurkurra ...] to accept [his] praye[rs ...] to overthrow his enemy (and) to kill [his ...]." This piece of information clearly indicates that the inscription was a letter (šipirtu) from Ashurbanipal to the god Aššur, the usual recipient of such texts. Unlike the subscript of the best-known letter to a god composed after Sargon II's eighth campaign, the scribe did not provide any supplemental information, nor did he record the (ceremonial) number of dead soldiers,[22] and, thus, one cannot rule out the possibility that this tablet is also a draft that would have been reworked/modified before the ceremony during which this letter is assumed to have been read aloud to Assyria's national god in Aššur. The scribal note added to K 3040+ (text no. 79) states that its contents were the "third extract" of an inscription and that the inscription was "not complete," thus indicating that longer inscriptions, mostly annalistic texts, could be written on a series of tablets.[23] This text, which more or less duplicates several inscriptions written on clay prisms,[24] was written on four tablets of the double-column format. Tablets I and II would have contained the inscription's prologue and reports of Ashurbanipal's first five campaigns; Tablet III (K 3040+) was inscribed with accounts of the king's sixth campaign (= Elam 1) and seventh campaign (= Elam 2); and Tablet IV would have been inscribed with a description of the eighth campaign (= Elam 3, Gambulu, Arabs 1) and the building report (perhaps a description of the construction of the House of Succession or the armory at Nineveh).[25]

Figure 4. An example of a tablet with a subscript: K 3040+ (text no. 79). © Trustees of the British Museum.

The most detailed, as well as perhaps the most interesting, Ashurbanipal subscript is written on K 2411 (text no. 223 = Grayson and Novotny, RINAP 3/2 pp. 228–231 Sennacherib 162). It reads:

This scribal notation records that Ashurbanipal had inscription(s) of his grandfather Sennacherib removed from the pleasure bed of the deities Marduk and Zarpanītu and the throne of the god Bēl (Marduk) before having those same objects refurbished and reinscribed with his own texts. Sennacherib's texts, which were deemed highly inappropriate since they were addressed to the god Aššur (instead of Marduk), were copied onto tablets before the inscriptions were destroyed. K 2411 was one of the products of that event.[26] From this short note, it is certain that in 655 (the eponymy of Awiānu) Ashurbanipal returned to Babylon the pleasure bed of Marduk and Zarpanītu that his grandfather Sennacherib had taken to Assyria and dedicated to the god Aššur after he had looted Esagil in 689; the bed was placed in Kaḫilisu, the bed chamber of the goddess Zarpanītu (as is recorded in several inscriptions). That musukkannu-wood bed needed to be refurbished before it was sent back to Babylon from the city of Aššur (Baltil). Ashurbanipal had his scribes copy onto tablets the inscription that Sennacherib had written on its gold plating before having that text removed from the metal plating and replaced with his own commemorative text. It would have been offensive to the god Marduk to have sent that bed back with an inscription dedicated to Aššur on it. Ashurbanipal did the same thing with Marduk's throne. In addition to making copies of his grandfather's inscriptions, Ashurbanipal had his scribes write out detailed descriptions of the objects.

As for the final unique subscript on a tablet pertaining to inscriptions of Ashurbanipal, the scribal notation on K 2674+ (text no. 161) states that the tablet was a "copy of the writing board that was read aloud before the king," and, thus, likely it was an archival copy of a collection of draft epigraphs that were presented to Ashurbanipal for approval; it is certain that the king approved some of these short texts for use since a few of these are known from sculpted orthostats lining the walls of the South-West Palace and North Palace at Nineveh. This is particularly interesting since there is no scholarly consensus on the precise relationship between the epigraphs accompanying wall reliefs in the Nineveh palaces and the epigraphs included in the numerous collections of epigraphs written on clay tablets (of various shapes, sizes, and formats), especially as very few of these are known from sculpted limestone slabs lining rooms of Sennacherib's and Ashurbanipal's royal residences.[27]

As a rule, tablets inscribed with inscriptions of Ashurbanipal are not dated; the same is true for the inscriptions of Esarhaddon, Sennacherib, and Sargon II written on clay tablets.[28] Only K 2411 (text no. 223) bears a date: The subscript of that tablet refers to the 27th of Simānu (III) of the eponymy of Awiānu (655). The date provided, however, is not for the month, day, and year that the tablet itself was inscribed, but rather for when the bed and throne of Marduk (Bēl) were reportedly returned to Babylon. Given the precision of the date, it is possible that this archival copy of the texts inscribed on it was written shortly after III-27-655, assuming, of course, that the date is correct.[29]

Given the fragmentary state of preservation of much of the known Ashurbanipal corpus, there is still a great deal of work to be done with this important group of texts. Editing the material together in a single place, as well as making the editions available in an annotated (lemmatized), open-access format, will hopefully inspire current and future students and scholars to examine these rich, ancient compositions in closer detail, perhaps even leading to the discovery of new joins and the identification of additional fragments. Given the technological advances in Assyriology over the past decade, as well as the growing repositories of digital photographs and text editions, the sky is the limit for future studies of Assyrian royal inscriptions.

Notes

[16] For a discussion of the tablets with Sennacherib's inscriptions, see Grayson and Novotny, RINAP 3/2 pp. 5–8.

[17] For some details on this horizontal tablet format (1:2 ratio), see Radner, Nineveh 612 BC pp. 72–73 (with fig. 8).

[18] For a brief overview of Ashurbanipal's lion hunts, see Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 pp. 26–27.

[19] Once the scribe added the number notation between the columns, he used his stylus to strike through the lines in col. iv as he no longer needed those notes.

[20] See the commentary of text no. 220 (L4) for further details.

[21] Text no. 225 is the Assyrian version of text no. 224. Note that some cylinder inscriptions of Sennacherib also record the number of lines. See, for example, Grayson and Novotny, RINAP 3/1 p. 40 Sennacherib 1 (First Campaign Cylinder) line 95 and p. 69 Sennacherib 4 (Rassam Cylinder) line 95.

[22] The subscript of AO 5372 + (Frame, RINAP 2 pp. 306–307 Sargon II 65 lines 426–430) reads: "One charioteer, two cavalrymen, (and) three light infantrymen were killed. Ṭāb-šār-Aššur, the chief treasurer sent the chief (enemy) informers to the god Aššur. Tablet of Nabû-šallimšunu, the chief royal scribe, chief tablet-writer (and) scholar of Sargon (II) king of Assyria, (and) son of Ḫarmakki, the royal scribe, an Assyrian. (This report) was brought in the eponymy of Ištar-dūrī, the governor of Arrapḫa." Compare the subscript of K 2852+, a letter of Esarhaddon to Aššur (Leichty, RINAP 4 p. 85 Esarhaddon 33 Tablet 2 iv 11´–13´): "I am sending the first report to the god Aššur, my lord, by so-and-so. One charioteer, two cavalrymen, (and) three scouts are dead." A.L. Oppenheim has argued that letters to gods were "not to be deposited in silence in the sanctuary, but to be actually read to a public that was to react directly to their contents" and that "they replace in content and most probably in form the customary oral report of the king or his representative on the annual campaign to the city and the priesthood of the capital" (JNES 19 [1960] p. 143). With regard to this genre of royal inscription, see, for example, Borger, RLA 3/8 (1971) pp. 575–576; Oppenheim, JNES 19 (1960) pp. 133–147; and Pongratz-Leisten in Hill, Jones, and Morales, Experiencing Power pp. 295–302.

[23] Above the subscript (text no. 79 iv 15´), the scribe wrote out the catch line "on my eighth campaign." This is one of only two preserved catch lines on a tablet inscribed with a text of Ashurbanipal. The other is on K 2640 (text no. 95), which is the second extract of an inscription written on three tablets; the now-missing subscript, which was written on the top edge of the tablet, would have read 2-ú nis-ḫu NU AL.TIL, "second extract, (inscription) not complete." At the present time, there is one other preserved subscript stating that a text is an excerpt: Leichty, RINAP 4 p. 109 Esarhaddon 48 (AsBbA) lines 109–110 records that its contents were an "(inscription) that is on a stele, on the left, first excerpt."

[24] The contents of K 3040+ (text no. 79) duplicates part of the military narration of text nos. 3 (Prism B), 4 (Prism D), 6 (Prism C), 7 (Prism Kh), and 8 (Prism G). See the commentary of that text for further details.

[25] It is certain that K 30+ (text no. 86) is not the fourth and final tablet of the four tablets inscribed with this long annalistic text since the contents of the two tablets duplicate one another.

[26] K 8664 (Grayson and Novotny, RINAP 3/2 pp. 225–228 Sennacherib 161) was the other product of the removal of Sennacherib's inscriptions written on Marduk's cult objects. See Grayson and Novotny, RINAP 3/2 pp. 8 and 225–228 for further details.

[27] For discussions on the matter, see in particular Reade, Design and Decoration pp. 326–334; Gerardi, Ashurbanipal's Elamite Campaigns pp. 96–99; Kaelin, Bildexperiment pp. 9–78 and 93–114, and J.M. Russell, Writing on the Wall pp. 156–209.

[28] Sargon II's letter to the god Aššur (Frame, RINAP 2 pp. 271–307 Sargon II 65) is dated to "the eponymy of Ištar-dūrī, governor of Arrapḫa (614)."

[29] The date seems to conflict with the Šamaš-šuma-ukīn Chronicle (Grayson, Chronicles p. 129; Glassner, Chronicles pp. 210–211), which states that the bed of the god Marduk was returned during the fourteenth year of Šamaš-šuma-ukīn (654), which is the thirteenth regnal year of Ashurbanipal (= the eponymy of Aššur-nāṣir). It is possible that the composer(s) of that chronographic text erroneously provided Ashurbanipal's regnal years instead of Šamaš-šuma-ukīn's. The reliability of the information provided in Babylonian Chronicles will be discussed in more detail in the introduction of Part 3.

Jamie Novotny

Jamie Novotny, 'Clay Tablets', RINAP 5: The Royal Inscriptions of Ashurbanipal, Aššur-etel-ilāni, and Sîn-šarra-iškun, The RINAP/RINAP 5 Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, 2022 [http://oracc.org/rinap/rinap5/RINAP52Introduction/SurveyoftheInscribedObjects/ClayTablets/]