Babylon, Part 1

104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115

104 [/rinap/rinap4/Q003333/]

Five fragments of heptagonal clay prisms contain an Akkadian inscription recording the rebuilding of Babylon and Esagil, the temple of the god Marduk in Babylon, by Esarhaddon. The text is dated to Esarhaddon's accession year (šanat rēš šarrūti, MU.SAG.NAM.LUGAL.LA), which should refer to 681 BC, but from the events mentioned in this inscription it is clear that the prisms were inscribed much later, presumably no earlier than the last month of 674 (see Frame, Babylonia p. 67). This text is commonly referred to as Babylon (Prism) A (Bab. A).

Access the composite text [/rinap/rinap4/Q003333/] or the score [/rinap/scores/Q003333/score] of Esarhaddon 104

Sources [/rinap/scores/Q003333/sources]:

| (1) BM 078223 [/rinap/sources/P345512/] (Bu 1888–05–12, 0077 + Bu 1888–05–12, 0078 + Bu 1888–05–12, -) | (2) VA 08420 [/rinap/sources/P450501/] (Ass 08000) |

| (3) MAH 15877 [/rinap/sources/P423861/] | (4) BM 060032 [/rinap/sources/P450502/] (AH 1882–07–14, 4442) |

| (5) BM 030153 [/rinap/sources/P450503/] |

Commentary

Ex. 1 is written in an archaizing Neo-Babylonian script, exs. 2–3 are written in Neo-Assyrian script, and exs. 4–5 are written in contemporary Babylonian script. Exs. 1–2 and 4 have horizontal rulings separating each line. Ex. 1 has Assyrian hieroglyphs on the top and bottom; for these see text no. 115. When possible, the restorations are based on text no. 105 (Babylon C). A score for this inscription is presented on the CD-ROM.

Ex. 6 (MMA 86.11.342 + CBS 1526) of the print version of RINAP 4 has been removed from the online versions (edition, score, and bibliography) since those pieces join BM 78247 (text no. 107). An edition of BM 78247 + MMA 86.11.342 + CBS 1526 is now presented as text no. 107 (Babylon F); see the commentary of that text for further information. The most notable change that has resulted from the removal of MMA 86.11.342 + CBS 152 from the edition is the deletion of v 39–45.

Moreover, the current online version of text no. 104 differs from the 2011 print edition of RINAP 4 in a few places. These are: (1) iii 32–34 (changes based on further examination by J. Novotny); and (2) iv 18–23 (see Novotny, NABU 2015/3 pp. 127–128 no. 78). In addition, a few, minor typographical have been corrected (see Novotny, SAAB 19 [2011-2012] pp. 29-86 passim).

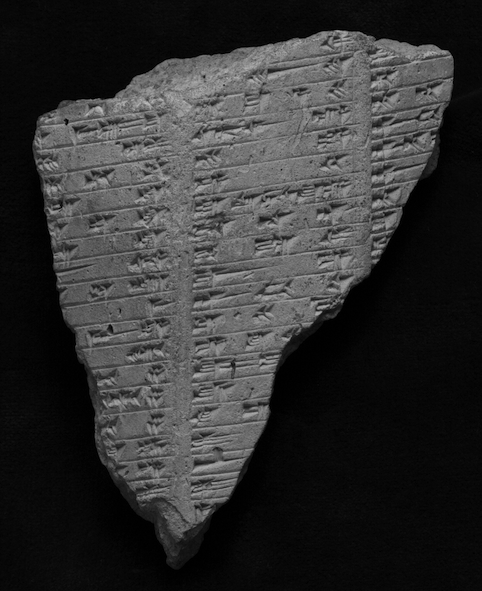

CBS 1526 (text no. 104 ex. 6), a fragment of a prism of Esarhaddon recording the rebuilding of Esagil and Babylon.

Bibliography

105 [/rinap/rinap4/Q003334/]

Two decagonal clay prisms have an Akkadian inscription commemorating the restoration of Babylon and Esagil, the temple of the god Marduk, by Esarhaddon. The text is dated to Esarhaddon's accession year (šanat rēš šarrūti, MU.SAG.NAM.LUGAL.LA), which should refer to 681 BC, but from the events mentioned in this inscription it is clear that the inscription was composed much later, presumably no earlier than the last month of 674 (see Frame, Babylonia p. 67). This text is commonly referred to as Babylon (Prism) C (Bab. C).

Access the composite text [/rinap/rinap4/Q003334/] or the score [/rinap/scores/Q003334/score] of Esarhaddon 105

Sources [/rinap/scores/Q003334/sources]:

(2) BM 078224 + BM 132294 [/rinap/sources/P345513/] (Bu 1888–05–12, 0079 + 1958–04–12, 0028)

Commentary

Both exemplars were purchased by E.A.W. Budge at Babylon and are registered as coming from Hillah. The script of both exemplars is contemporary Babylonian and horizontal rulings separate each line. A score for this inscription is presented on the CD-ROM. The line arrangement and master line generally follow ex. 1.

The current online version of text no. 105 differs from the 2011 print edition of RINAP 4 in a few places. These are: (1) iv 26–28 (changes based on further examination by J. Novotny); and (2) v 47–vi 4 (see Novotny, NABU 2015/3 pp. 127–128 no. 78). After a careful re-examination of ex. 1 by J. Novotny, the line count of col. vi has changed: There are two missing lines at the beginning of the column and, therefore, the line count of the online version differs from the print version in that column by two lines. In addition, a few, minor typographical have been corrected (see Novotny, SAAB 19 [2011-2012] pp. 29-86 passim).

Bibliography

106 [/rinap/rinap4/Q003335/]

An Akkadian inscription of Esarhaddon describing the rebuilding of Babylon and Esagil, the temple of the god Marduk in Babylon, is found on four prisms and a tablet, all probably from Babylon. The text is dated to Esarhaddon's accession year (šanat rēš šarrūti, MU.SAG.NAM.LUGAL.LA), which should refer to 681 BC, but from the events mentioned in this inscription it is clear that it was composed much later, presumably no earlier than the last month of 674 (see Frame, Babylonia p. 67). This text is commonly referred to as Babylon (Prism) E (Bab. E).

Access the composite text [/rinap/rinap4/Q003335/] or the score [/rinap/scores/Q003335/score] of Esarhaddon 106

Sources [/rinap/scores/Q003335/sources]:

| (1) BM 078225 (+) Hirayama collection - [/rinap/sources/P345515/] (Bu 1888–05–12, 0080) | (2) AO 07736 (+) BM 078246 (+) MMA 86.11.278 [/rinap/sources/P450504/] (Bu 1888–05–12, 0101) |

| (3) BM 042668 [/rinap/sources/P450505/] (1881–07–01, 0430) | (4) BM 034899 [/rinap/sources/P285940/] (Sp 2, 411) |

| (5) BM 078248 [/rinap/sources/P345516/] (1888–05–12, 0103) |

Commentary

Exs. 1–2 and 5 are registered as coming from Hillah, but they may originate from Babylon. The script of exs. 1 and 4 is Babylonian. Ex. 2 is written in an archaizing Neo-Babylonian script. In contrast, the script of exs. 3 and 5 is Neo-Assyrian. Ex. 1 is an octagonal prism and exs. 2–3 and 5 are all hexagonal prisms; ex. 4 is a small piece of a multi-column tablet.

AO 7736 once belonged to H. Pognon. Although no details about its original purchase have been published, it was probably acquired at or near Babylon. BM 78246 is part of the Budge 88-5-12 collection of the British Museum, objects that were purchased by E.A.W. Budge in 1888. At Babylon, Budge purchased "several large pieces of cylinders [= prisms] of Esarhaddon for a majîdî (dollar) each." Note, however, that BM 78246 is registered as coming from Hillah. J. Nougayrol (AfO 18 [1957–58] p. 314, with n. 1) recognized the join between AO 7736 and BM 78246; this join was not included in the print version of RINAP 4. MMA 86.11.278 was purchased from the Reverend William Hayes Ward by the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York) in 1886; the fragment was acquired when Ward led the Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Expedition to Babylonia in 1884–85. J. Novotny recently joined MMA 86.11.278 to AO 7736 (+) BM 78246 on the basis of script (same scribe), column divisions, and text lineation; details will be presented in a forthcoming article. The break down of the three fragments is as follows: (1) AO 7736 = i 3´–19´, iii 11´–16´, iv 1´–47´, v 1´–45´, and vi 11–45; (2) BM 78246 = i 1´–19´, ii 1´–22´, and iii 1´–16´; and (3) MMA 86.11.278 = i 1–14, ii 1–14, and vi 1–18. AO 7736+ (=RINAP 4 exs. 2, 6–7) preserves ca. 72% of the inscription and is presently the best preserved exemplar of Babylon E. Despite the joins between exs. 2, 6, and 7, the online edition still principally follows the edition published in RINAP 4. Note, however, that iii 34–56 are now iii 34–55 since the "blank" line (iii 34) of the print edition was removed since none of the known exemplars have a blank line in this part (or any part) of the inscription; and that vi 6-61 are now vi 5-60 since the assumed omitted line vi 5 was deleted since neither ex. 2 nor ex. 3 appear to have included that proposed scribal error. Furthermore, exs. 2 and 6–7 have been merged in the score (and bibliography); all three pieces are now regarded as ex. 2. In addition, a few, minor typographical errors in the edition have been corrected (see Novotny, SAAB 19 [2011-2012] pp. 29-86 passim).

Bibliography

107 [/rinap/rinap4/Q003336/]

A fragment of a ten-sided prism contains an inscription of Esarhaddon describing the rebuilding of Babylon and Esagil, the temple of the god Marduk in Babylon. This text is commonly referred to as Babylon (Prism) F (Bab. F).

Access Esarhaddon 107 [/rinap/rinap4/Q003336/]

Source:

Commentary

Since 1896, Babylon F has been known from only a single fragment: BM 78247 (Bu 88-5-12,102), a fragment of a solid clay prism in the British Museum (London) that is registered as coming from Hillah. Its script is Neo-Assyrian and it was thought to have been part of an eight-sided prism, with the piece coming from the top of three columns. As it turns out, BM 78247 belongs to the same prism as MMA 86.11.342 (+) CBS 1526, a large prism fragment in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York) and a small fragment in the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (Philadelphia). The join of MMA 86.11.342 and CBS 1526 was proposed by M. Rutz and subsequently verified by the author; CBS 1526 is commonly referred to as Babylon (Prism) AC (Bab. AC). The joined New York and Philadelphia pieces were regarded as being an exemplar of Babylon A since the contents of col. i´ 13´–19´ deviated from Babylon C and, thus, that passage was regarded as filling in part of a gap then missing in Babylon A. BM 78247 col. iii´ 7–25 joins MMA 86.11.342+ col. i´ 1´–19´. The join was recognized by J. Novotny on the basis of the shape of the fragments, the script (Neo-Assyrian, with regular use of wide blank spaces between signs), and the width of the columns (narrow columns that accommodated only one or two words per line); see Novotny, JCS 67 (2015) pp. 164-168.

The three pieces preserve parts of the last six columns of a tall, solid ten-sided clay prism. Parts of 160 lines (31.25%) of the approximately 500 lines of text originally inscribed on the prism are extant. BM 78247 preserves col. i´ 1–3, col. ii´ 1–14, and col. iii´ 1–27. MMA 86.11.342 preserves col. iii´ 7–25, col. iv´ 1´–25´, col. v´ 1´–23´, and col. vi´ 1´–22´. CBS 1526 preserves col. iv´ 26´–43´, col. v´ 23´–42´, and col. vi´ 23´–32´. The restorations are generally based on text nos. 104 and 105. Assyrian hieroglyphs are stamped on the top (see text no. 115). The online version of text no. 107 is an electronic version of the edition published by Novotny in JCS 67 (pp. 164-168).

Bibliography

108 [/rinap/rinap4/Q003337/]

An Akkadian inscription of Esarhaddon on a five-sided prism from Nineveh describes the rebuilding of Babylon. The text is dated to Esarhaddon's accession year (šanat rēš šarrūti, MU.SAG.NAM.LUGAL.LA), which should refer to 681 BC, but from the events mentioned in this inscription it is clear that it was composed much later, presumably no earlier than the last month of 674 (see Frame, Babylonia p. 67). This text is commonly referred to as Babylon G (Bab. G) and edited with the Babylon inscriptions, rather than with texts from Nineveh, since it duplicates texts (reportedly) from that city and since it concerns the rebuilding of Esagil and Babylon.

Access Esarhaddon 108 [/rinap/rinap4/Q003337/]

Source:

Commentary

As suggested by A.R. Millard (AfO 24 [1973] pp. 118–119), BM 98972 (this text) probably belongs to the same prism as BM 122617 + BM 127846 (text no. 109). This non-physical join was not included in the print version of RINAP 4. J. Novotny (Novotny, JCS 67 [2015] p. 162) has further examined the pieces and has verified Millard's proposed join, thus confirming that BM 98972 and BM 122617 + BM 127846 are both pieces of the same five-sided prism. The two fragments jointly preserve parts of about half of the contents of Babylon G. However, since the join between the objects cannot be proved with absolute certainty, the online version of text nos. 108 and 109 are still presented individually; notes have been added to help the reader piece together the narrative of the text(s).

The current online version of text no. 108 differs from the 2011 print edition of RINAP 4 in a few places. These changes are based on further collations by J. Novotny; see SAAB 19 (2011-2012) pp. 29-86 passim and JCS 67 (2015) pp. 162-164.

Bibliography

109 [/rinap/rinap4/Q003338/]

A fragment of a hollow pentagonal prism from Nineveh contains an inscription concerning the rebuilding of Babylon. This text is edited with the Babylon inscriptions, rather than with texts from Nineveh, since it duplicates texts (reportedly) from that city and since it concerns the rebuilding of Esagil and Babylon.

Access Esarhaddon 109 [/rinap/rinap4/Q003338/]

Source:

Commentary

BM 122617 + BM 127846 (this text) probably belongs to the same five-sided prism as BM 98972, as suggested by A.R. Millard (AfO 24 [1973] pp. 118–119) and J. Novotny (Novotny, JCS 67 [2015] p. 162); for further details, see the commentary of text no. 108. Since the suggested non-physical join between the objects cannot be proved with certainty, the online version of text nos. 108 and 109 are still presented individually, but with added notes to aid the reader.

The current online version of text no. 109 differs from the 2011 print edition of RINAP 4 in a few places. These changes are based on further collations by J. Novotny; see SAAB 19 (2011-2012) pp. 29-86 passim and JCS 67 (2015) pp. 162-164.

Bibliography

110 [/rinap/rinap4/Q003339/]

A fragment of a hexagonal prism contains an inscription commemorating Esarhaddon's reconstruction of Babylon. Although its provenance is not known, this text is edited with the Babylon inscriptions since it duplicates texts (reportedly) from that city and since it concerns the rebuilding of Esagil and Babylon.

Access Esarhaddon 110 [/rinap/rinap4/Q003339/]

Source:

Commentary

Parts of three columns are preserved. The preserved text duplicates text no. 104 (Babylon A) vi 1–9; text no. 105 (Babylon C) vi 20–27 and viii 2–14; and text no. 116 (Babylon B) rev. 23. When possible, the restorations are based on those inscriptions.

The current online version of text no. 110 differs from the 2011 print edition of RINAP 4 in a few places. These changes are based on further examinations of the inscription by the author, G. Frame, and J. Novotny; see Leichty in Spar, CTMMA 4 pp. 257-260 no. 158 and pl. 121. Note that the line counts of col. iii' of the online edition differ from those of the 2011 print version; the faint traces of part of a sign in iii' 1' were overlooked during the preliminary examination of the object.

Bibliography

111 [/rinap/rinap4/Q003340/]

An Akkadian inscription on a fragment of an octagonal prism describes the rebuilding of Babylon and Esagil, the temple of the god Marduk in Babylon. The text is dated to Esarhaddon's accession year (šanat rēš šarrūti, MU.SAG.LUGAL.LA), which should refer to 681 BC, but from the events mentioned in this inscription it is clear that it was composed much later, presumably no earlier than the last month of 674 (see Frame, Babylonia p. 67). Although its provenance is not known, this text is edited with the Babylon inscriptions since it duplicates texts (reportedly) from that city and since it concerns the rebuilding of Esagil and Babylon.

Access Esarhaddon 111 [/rinap/rinap4/Q003340/]

Source:

Commentary

The lower parts of five columns are preserved. Assyrian hieroglyphs are stamped on the base (see text no. 115). The preserved text duplicates, with minor variation, text no. 104 (Babylon A) i 22–36, iii 49–iv 8, 18–20, v 18–33, and vi 28–37; text no. 105 (Babylon C) i 24–39, v 4–14, 38–42, 47–vi 2, vii 21–38, and viii 37–ix 5; text no. 106 (Babylon E) vi 52–56; and text no. 107 (Babylon F) viii 1–10. When possible, the restorations are based on those parallels.

The current online version of text no. 111 differs from the 2011 print edition of RINAP 4 in a few places. These changes are based on further examinations of the inscription by the author, G. Frame, and J. Novotny. See Leichty in Spar, CTMMA 4 pp. 260-263 and pls. 122-125; Novotny, SAAB 19 (2011-2012) pp. 29-86 passim and NABU 2015/3 pp. 127–128 no. 78. Note that the line counts of cols. i and vii of the online edition differ from those of the 2011 print version; i 8' and vii 1' were overlooked during the preliminary examination of the object.

Bibliography

112 [/rinap/rinap4/Q003341/]

An inscription on a fragment of a five-sided prism from Sippar recounts Esarhaddon's deeds. The script is contemporary Babylonian and horizontal rulings separate each line. Based on the king's titulary, it is certain that the text dates to after 671 BC. This text is edited with the Babylon inscriptions since it duplicates texts (reportedly) from that city and since it concerns the rebuilding of Esagil and Babylon.

Access Esarhaddon 112 [/rinap/rinap4/Q003341/]

Source:

Bibliography

113 [/rinap/rinap4/Q003342/]

An inscription of Esarhaddon on a solid cylinder from Babylon describes the rebuilding of Eniggidrukalamasuma, the temple of the god Nabû of the ḫarû in Babylon. The text, which is written in contemporary Babylonian script and with each line separated by a horizontal ruling, dates to after Ayyāru (II) 672 BC since Ashurbanipal and Šamaš-šuma-ukīn are mentioned as heir designates of Assyria and Babylon.

Access Esarhaddon 113 [/rinap/rinap4/Q003342/]

Source:

Bibliography

114 [/rinap/rinap4/Q003343/]

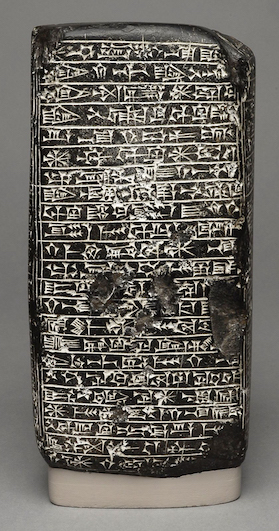

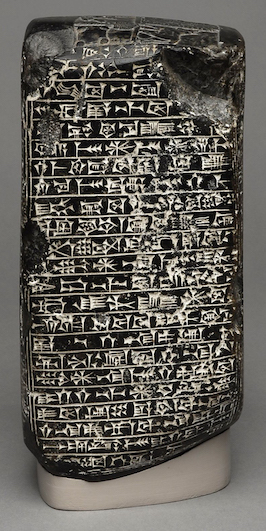

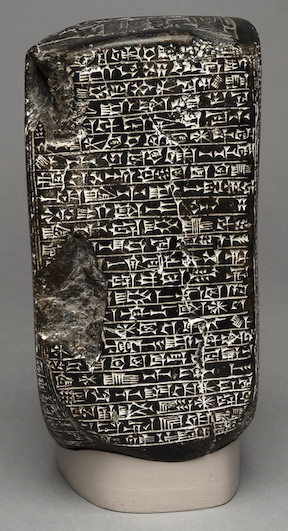

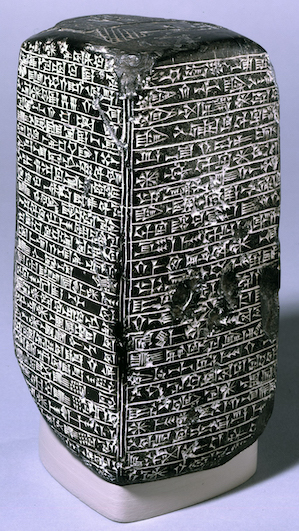

An Akkadian inscription on a black basalt cuboid monument describes the rebuilding of Babylon and Esagil, the temple of the god Marduk in Babylon. This monument is known as Lord Aberdeen's Black Stone and its text is commonly referred to as Babylon D (Bab. D).

Access Esarhaddon 114 [/rinap/rinap4/Q003343/]

Source:

Commentary

Assyrian hieroglyphs are carved on the top (see text no. 115) and the script is archaizing Neo-Babylonian. The fourth Earl of Aberdeen purchased the object sometime around the 1820s and presented it to the British Museum in 1860. Rawlinson, when he published his copy in 1R (1861), stated that Lord Aberdeen's Black Stone came from Nineveh, but without providing evidence for its provenance. Finkel and Reade (ZA 86 [1996] p. 254) have suggested that it probably comes from Babylon since that site was the normal source for antiquities at the time Lord Aberdeen purchased it.

The current online version of text no. 114 differs slightly from the 2011 print edition of RINAP 4 in a few places. These changes are based on further collations by J. Novotny.

BM 91027 (text no. 114), Lord Aberdeen's Black Stone col. i, a cuboid monument of Esarhaddon recording the rebuilding of Babylon and Esagil.

BM 91027 (text no. 114), Lord Aberdeen's Black Stone col. ii, a cuboid monument of Esarhaddon recording the rebuilding of Babylon and Esagil.

BM 91027 (text no. 114), Lord Aberdeen's Black Stone col. iii, a cuboid monument of Esarhaddon recording the rebuilding of Babylon and Esagil.

BM 91027 (text no. 114), Lord Aberdeen's Black Stone cols. iv and i, a cuboid monument of Esarhaddon recording the rebuilding of Babylon and Esagil.

Bibliography

115 [/rinap/rinap4/Q003344/]

In text no. 104 vii 10–12, the phrase lumāšē tamšīl šiṭir šumīya ēsiq, "I depicted lumāšē, representing the writing of my name, on them" occurs. This undoubtedly refers to symbols that have been interpreted as a cryptographic royal inscription of Esarhaddon and that are found upon three clay prisms and one stone monument, all probably from Babylon. These symbols have been referred to as Assyrian hieroglyphs or astroglyphs, which may have been inspired by Assyrian encounters with Egyptian hieroglyphs. The texts that are found on the objects with the Assyrian hieroglyphic inscriptions are: text no. 104 ex. 1 (Babylon A), text no. 107 (Babylon F), text no. 111, and text no. 114 (Babylon D = Lord Aberdeen's Black Stone). Inscriptions of this kind have so far only been identified for the kings Sargon II and Esarhaddon, and the cryptography did not follow Egyptian hieroglyphic writing directly but rather appears to have been inspired by the latter's pictographic character. Although it is likely that these symbols represent Esarhaddon's name and royal title(s), the matter of how to read the hieroglyphs, both individually and as a group, is still not settled.

While the interpretations offered below are extremely ingenious, I find them to be clever but dubious, as several of the readings are rather forced. I am, however, not able to offer a better solution. My misgivings are as follows:

1) The name. Esarhaddon had at least three names, Aššur-aḫu-iddin, Aššur-etel-ilānī-mukīn-apli, and an Aramaic name that we do not know. While his throne name Aššur-aḫu-iddin is the most likely one to be on these monuments, it is not certain that this is the case.

2) The language. We should probably expect the language to be Akkadian, but four instances on three exemplars are written counterclockwise. Aramaic is written right to left and hieroglyphic Egyptian is normally written from right to left but may be written in any direction. I do not know if this is meaningful.

3) Are the Assyrian hieroglyphs read syllabically or logographically? Akkadian could allow either or both.

4) All the solutions find themselves with too many hieroglyphs for the name alone and try to solve the problem by adding a pronoun or title after the name. This is where serious guesswork enters, and while I would not rule out any of these solutions, I remain unconvinced at this time.

The presentation which follows does not pretend to indicate the interpretations of the individual signs in a fully satisfactory manner and the reader must consult the original publications to understand the views and interpretations of the respective scholars.

Access Esarhaddon 115 [/rinap/rinap4/Q003344/]

| (1) BM 091027 [/rinap/sources/P453468/] (1860–12–1, 0001) | (2) BM 078247 + MMA 86.11.342 + CBS 01526 [/rinap/sources/P345512/] (Bu 1888–05–12, 0102; CBS 01526: Khabaza (27–05-[18]95)) |

| (3) BM 078247 [/rinap/sources/P345518/] (Bu 88–05-12, 0102) | (4) MMA 86.11.283 [/rinap/sources/P453467/] |

Commentary

Ex. 1 is a stone monument and exs. 2–4 are clay cylinders. All of these pieces may originate from Babylon. In ex. 1 the symbols are carved in relief in two registers atop the stone monument, and the consensus is that the symbols are to be read left to right. The order found on ex. 1 indicates the starting point in exs. 2–4, where the symbols were stamped in a counterclockwise circular pattern on one or both ends of each prism, apparently by at least two different stamps. Each hieroglyphic text has eight symbols in the same basic order, with one major variant and a few minor stylistic variants. In ex. 1 symbol 4 is a bull, while in exs. 2–4 symbol 4 is a lion. Note that a lion is incised facing the beginning of some of the royal inscriptions on stone vases from Aššur (e.g., text no. 72). In ex. 1 symbol 1 has a stylized tree decorating the base of the podium and the divine horns on the headdress are more pronounced than in exs. 2–4. In ex. 1 symbol 3 is a stylized tree, while in exs. 2–4 the tree is greatly simplified.

D. Nadali (Iraq 70 [2008] pp. 87–104) has tentatively ascribed to Esarhaddon the figural elements (bull's leg, vegetation, man's hand and bare head) on eight high-relief bricks, seven of which are known to have been excavated by R.C. Thompson in his first season of excavations at Nineveh (1927–28). These pieces are fragmentary, and, as Nadali notes, another possibility is that they came from the reign of Sargon II.

BM 91027 (text no. 115), Lord Aberdeen's Black Stone, a cuboid monument of Esarhaddon recording the rebuilding of Babylon and Esagil with Assyrian hieroglyphs incised on its top.

BM 78223 (text no. 115), a fragment of clay prism of Esarhaddon recording the rebuilding of Babylon and Esagil with Assyrian hieroglyphs stamped on its top.

BM 78223 (text no. 115), a fragment of clay prism of Esarhaddon recording the rebuilding of Babylon and Esagil with Assyrian hieroglyphs stamped on its base.

BM 78247 (text no. 115), a fragment of clay prism of Esarhaddon recording the rebuilding of Babylon and Esagil with Assyrian hieroglyphs stamped on its top.

MMA 86.11.283 (text no. 115), a fragment of clay prism of Esarhaddon recording the rebuilding of Babylon and Esagil with Assyrian hieroglyphs stamped on its base.

Bibliography

Erle Leichty

Erle Leichty, 'Babylon, Part 1', RINAP 4: Esarhaddon, The RINAP 4 sub-project of the RINAP Project, 2025 [http://oracc.org/rinap/rinap4/RINAP4TextIntroductions/Babylon/]