- Home

- Explore RINAP Home Page

- Browse Online Corpus

- Access RINAP 3 Scores

- Access RINAP 3 Sources

- RINAP 3/1 Front Matter

- RINAP 3/1 Introduction

- RINAP 3/1 Text Introductions

- RINAP 3/1 Back Matter

- RINAP 3/2 Front Matter

- RINAP 3/2 Introduction

- RINAP 3/2 Text Introductions

- RINAP 3/2 Back Matter

- Oracc Lemmatization Colors

- Citing RINAP URLs

- Reusing RINAP material

- RINAP Downloads

Nineveh, Part 14

155 156 157 158 159 160 161 162 163

155 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003960/]

A fragment of a single-column tablet, possibly from the same tablet as text nos. 153–154, preserves part of an archival copy or a draft of an inscription of Sennacherib. The extant text contains parts of the prologue (Sennacherib's titulary), a statement about the god Aššur supporting Sennacherib as his earthly representative, passages about the king's work at Nineveh and the city's lack of an adequate water supply, and a passage describing the digging of a canal and the opening up of a canal's sluice gate. As far as it is preserved, the building report duplicates text no. 223, an inscription written on a cliff face at Ḫinnis-Bavian.

Access Sennacherib 155 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003960/]

Source:

Commentary

If DT 166 belongs to the same tablet as K 100 (text no. 153) and Rm 403 (text no. 154), then according to E. Frahm (Sanherib pp. 215–217 T 179) (1) obv. 1' of this text follows text no. 153 obv. 25 after a lacuna of undetermined length; (2) obv. 1'–5' and rev. 11'–12' of this text and no. 154 obv. 7'–11' and rev. 1'–2' contain parts of the same lines; and (3) text no. 153 rev. 1' follows rev. 12' of this text after a lacuna of undetermined length. Obv. 1'–3' contain the last lines of the list of Sennacherib's titulary; some of the epithets are known from an inscription from Aššur; see text no. 168 lines 15–19. Obv. 4'–7'a preserve part of a statement about the god Aššur making Sennacherib great and this passage is not duplicated exactly elsewhere in the known Sennacherib corpus; cf., for example, text no. 22 i 10–15 and text no. 230 lines 5b–8a. Obv. 7'b–13' contain passages about the king's work at Nineveh and the city's lack of an adequate water supply. The contents of obv. 7'b–8'a are known from text no. 17 v 23 and those of obv. 12'b–13'a duplicate text no. 223 line 7b. Rev. 1'–12' preserve part of the building report and these lines duplicate text no. 223 lines 23–31. The restorations are based on text no. 223 lines 7b and 23–31, text no. 230 lines 5b–8a, and text no. 168 lines 15–19. The text's line arrangement is conjectural.

Bibliography

156 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003961/]

A small clay tablet that probably comes from Nineveh has copies of three inscriptions that were on a royal seal of lapis lazuli. It was originally the seal of Šagarakti-Šuriaš, king of Babylonia, but Tukultī-Ninurta I seized it as booty during his conquest of Babylonia and had an inscription of his own added to the object. After his death, the seal returned to Babylonia, only to be taken as booty once again in late 689 by Sennacherib, who had his own inscription written on it.

Access Sennacherib 156 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003961/]

Source:

Commentary

The tablet contains inscriptions of three different kings — Šagarakti-Šuriaš (lines 8 and 12), Tukultī-Ninurta I (lines 1–3 and 9–11), and Sennacherib (lines 4–7) — plus a colophon (line 13). There are several scribal errors: Parts of the names of Shalmaneser and Karduniaš are omitted (lines 9 and 2 respectively), and there are sign-form errors in lines 2, 8, 10, and 12. The phrase šarik tadin (line 4) seems to be a euphemism masking the reality of the event that caused the seal to be taken back to Babylonia.

Bibliography

157 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003962/]

A small clay tablet, probably from Nineveh, contains drafts of two texts that were to be inscribed upon small cylinder-shaped beads at Sennacherib's command. The stones are said to have been brought back to Nineveh from Gala..., an otherwise unattested city. For the contents of the texts, cf. text nos. 102–131, which are all written on small cylinder-shaped beads.

Access Sennacherib 157 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003962/]

Source:

Bibliography

158 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003963/]

A fragment of a single-column clay tablet, probably from Nineveh, is inscribed with drafts or archival copies of two short inscriptions. Only the concluding formulae of the first text (Inscription A) is extant, while parts of all twenty-six lines of the second text (Inscription B) are preserved. The latter text, which is separated from the former by a horizontal ruling and written in a high literary style, describes the Tablet of Destinies and representations of the god Aššur and Sennacherib. Although Inscription B provides a wealth of information about Sennacherib's theological reforms, the precise context of the text is uncertain. The inscriptions were composed relatively late in Sennacherib's reign (post-689).

Access Sennacherib 158 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003963/]

Source:

Commentary

Parts of the obverse, reverse, bottom edge, left edge, and right edge are preserved. K 6177 + K 8869 is not a regular, finished tablet and the script is contemporary Babylonian, something unique for an inscription of this Assyrian king. The inscriptions written on this tablet are (first) drafts, or possibly later copies. With regard to the script, A.R. George (Iraq 48 [1986] p. 137) suggests that a Babylonian scribe was employed because southern scholars were better qualified to compose a text in high literary Standard Babylonian. E. Frahm (Sanherib p. 220) further postulates that Sennacherib had Babylonian priests brought to Assyria since they had the theological know-how to properly transfer Marduk's attributes to Aššur and that one of those priests was the scribe of this text. The purpose and context of the inscriptions are uncertain, due in part to the fact that the subscript (assuming the tablet had one on the reverse) is completely broken away. Because Inscription B (obv. 5'–rev. 11), the better preserved of the two inscriptions, is descriptive, rather than narrative, George (Iraq 48 [1986] pp. 133–144) proposes that that inscription is an extended epigraph, with appended concluding formulae, which was written on a now-lost (or never finished) monument. Regarding Inscription A (obv. 1'–4'), he notes that too little of it is preserved to be certain if that text is a second inscription on the same monument or if it was written on a completely different object. Moreover, George postulates that the images of Aššur and Sennacherib described in Inscription B were transposed onto the Tablet of Destinies, which is also described in this text, by Aššur's seal, the Seal of Destinies (Seal A of the Esarhaddon Vassal Treaties; see text no. 212 for further details), and, therefore, that text describes the Tablet of Destinies, a clay tablet sealed by the Seal of Destinies; for example, the tablets upon which Esarhaddon had his Vassal Treaties (Parpola and Watanabe, SAA 2 pp. 22–58 nos. 4–6) written were such tablets. Frahm (Sanherib p. 221) suggests that Inscription B (and possibly also Inscription A) may have been written on a metal object that also depicted the Tablet of Destinies, the god Aššur, and Sennacherib. He conjectures that such an object might have been (the plating on) the Dais of Destinies (parak šīmāti) in the Aššur temple at Aššur; Esarhaddon (Leichty, RINAP 4 p. 136 Esarhaddon 60 lines 26'–29'a) records that he reconstructed the Dais of Destinies entirely with zaḫalû- and ešmarû-metal. Given the absence of a subscript, George's and Frahm's interpretations must remain conjectural. A detailed discussion of this issue falls outside the scope of the present volume.

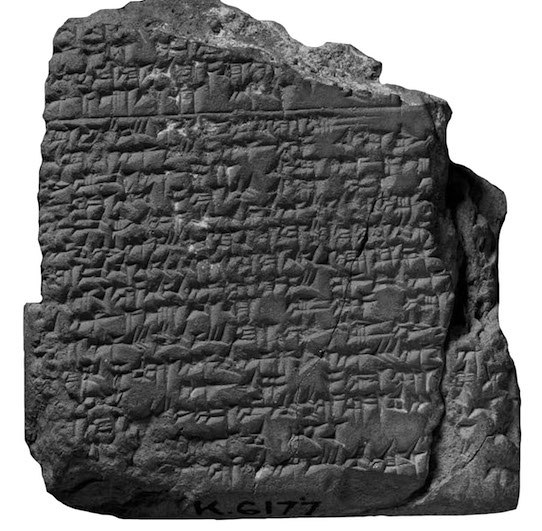

Obverse of K 6177 + K 8869 (text no. 158), a fragment of a single-column clay tablet inscribed with drafts (or copies) of two short inscriptions of Sennacherib.

Bibliography

159 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003964/]

K 5413a, a fragment of a single-column clay tablet that was probably discovered at Nineveh, is inscribed with a copy or draft of an inscription for a kettledrum dedicated by Sennacherib to the god Aššur. The first fourteen lines are preserved and these contain the opening dedication (obv. 1–6a), Sennacherib's name and titulary (obv. 6b–7a), and a report describing the fashioning of a bronze kettledrum (obv. 7b–14). Aššur's titulary in the opening dedication duplicates exactly that god's titles and epithets in a text written during Sennacherib's twenty-second regnal year (683) in which the king dedicates personnel to the newly constructed akītu-house at Aššur; see Kataja and Whiting, SAA 12 pp. 104–108 no. 86, esp. obv. 7–11. This text may thus also have been written towards the end of Sennacherib's reign, ca. 683.

Access Sennacherib 159 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003964/]

Source:

Bibliography

160 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003965/]

A draft of an interesting text recording the construction of an akītu-house (New Year's Temple) outside the western wall of the city Aššur is found on a small tablet that was probably discovered at Nineveh. In particular, the inscription describes scenes on the temple's bronze gate, a work of art depicting an epic battle between Aššur on the one hand and his entourage and Tiāmat and her horde of monsters on the other hand. According to the description, Assyria's chief god is raising his bow and riding in a chariot with the god Amurrû; at least twenty-five gods and goddesses are shown with him, some on foot and some in chariots. Sennacherib boasts in this text about a new bronze casting technique that he allegedly invented for the purpose of creating this gate. The inscription was composed relatively late in Sennacherib's reign (post-689) and it provides some information on Sennacherib's religious reforms after the destruction of Babylon in 689 (his 16th regnal year).

Access Sennacherib 160 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003965/]

Source:

Commentary

For some details about the horizontal tablet format (1:2 ratio) of K 1356, see Radner, Nineveh 612 BC pp. 72–73 (with fig. 8). All thirty-three lines are (partially) preserved. Line 1 is written on the top edge, lines 2–15 on the obverse, lines 16–17 on the bottom edge, lines 18–31 on the reverse, and lines 32–33 on the left edge. Lines 1–25 comprise the inscription proper; lines 26–31 provide information about the images described in lines 5–18 (the decoration on the gate) and lines 32–33 are scribal notes pertaining to lines 6b–8a and line 11; a horizontal ruling separates lines 25 and 26.

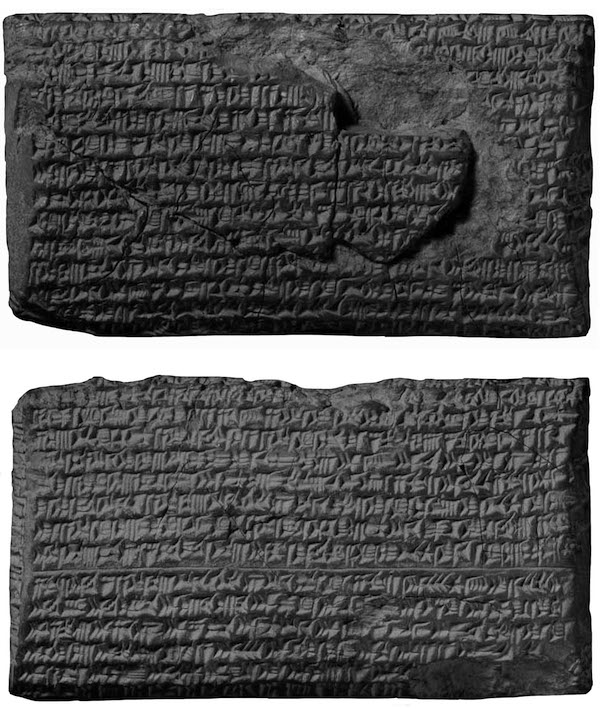

Obverse and reverse of K 1356 (text no. 160), a clay tablet inscribed with a copy of a text recording the construction of the New Year's Temple outside of Aššur.

Bibliography

161 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003966/]

In his 14th regnal year (655), Ashurbanipal had an inscription that Sennacherib had written on the metal plating decorating Marduk's pleasure bed and throne copied onto a single-column clay tablet; descriptions of those two pieces of cult furniture were recorded at that time. K 8664 is a fragment of that tablet. Only the first twenty lines of the dedication section addressed to the god Aššur, the last eight lines of the descriptions of Marduk's pleasure bed and throne, and the three-line subscript noting why Ashurbanipal had this tablet written are preserved. The inscription was dedicated to the god Aššur and was composed relatively late in Sennacherib's reign (post-689). The tablet was inscribed shortly before the one with text no. 162.

Access Sennacherib 161 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003966/]

Source:

Commentary

This tablet probably contains the original copy that Ashurbanipal had made before having Sennacherib's inscription removed from Marduk's pleasure bed and throne and having his own inscription written in their place. K 2411, the tablet inscribed with text no. 162, is likely a later copy of the contents of K 8664, with the addition of Ashurbanipal's replacement inscription. Both tablets were probably inscribed around the same time (655 = Ashurbanipal's 14th regnal year). According to the subscript written on this tablet (rev. 9'–11'), Sennacherib had the same text written on both plundered pieces of cult furniture; those objects were rededicated to the god Aššur at Aššur, after they were inscribed with that text. E. Frahm (Sanherib p. 226) proposes that K 8664 and K 2411 preserve parts of one and the same Sennacherib inscription; this text (K 8664) contains part of the dedication to Aššur and text no. 162 (K 2411) iii 1'–16' contain the end of the building report and the concluding formulae. Although this is likely true, the texts preserved on K 8664 and K 2411 have been edited separately here.

Bibliography

162 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003967/]

In 655, Ashurbanipal had one of his scribes copy on a two-column clay tablet an inscription that Sennacherib had had written on the metal plating decorating Marduk's pleasure bed and throne. K 2411, which is probably from Nineveh, is a fragment of that tablet. The Sennacherib inscription began on the obverse and ended in the upper part of the first column on the reverse (iii 1'–16'). That text is followed by descriptions of the pleasure bed and throne of Babylon's tutelary deity that Ashurbanipal had had recorded (iii 17'–35'), a five-line subscript noting why Ashurbanipal had this tablet written (iii 36'–40'), and the text of Ashurbanipal that replaced his grandfather's texts on the furniture (iv 1'–29'). The inscription, which was dedicated to the god Aššur (see text no. 161), was composed relatively late in Sennacherib's reign (post-689).

Access Sennacherib 162 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003967/]

Source:

Commentary

Despite Craig, ABRT 1 pp. 76–79, part of the obverse (the ends of the first five lines of col. ii) is preserved; this has not been noted previously. Furthermore, Craig did not copy or note the uninscribed 6.3 cm space at the end of col. iv; this fact has also not been mentioned in previous editions, translations, and studies. This omission has given rise to the misunderstanding that the texts on K 2411 copied by Craig in ABRT were all on the obverse (cols. i and ii). As already correctly recognized by M. Streck (Asb. pp. 292–303 no. 14) and D.D. Luckenbill (ARAB 2 pp. 387–390 §§1010–1018), this is not the case: Craig, ABRT 1 pp. 76–79 represent the reverse (cols. iii and iv) of K 2411. See Figure 22 on the next page.

This tablet may have been a copy of text no. 161, but with the new inscription of Ashurbanipal added. Contrary to B. Landsberger (Brief p. 25 n. 40), iii 1'–4' and iii 5'–16' are not parts of two different inscriptions; iii 1'–4' preserve the end of the building report and iii 5'–16' contain the concluding formulae. Based on the subscript of text no. 161 (rev. 9'–11'), E. Frahm (Sanherib p. 226) proposes that text no. 161 (K 8664) obv. 1–20 are the beginning of the inscription, the dedication to the god Aššur, and that this text (K 2411) iii 1'–16' are the end of the same inscription. Although this may well be true, the texts preserved on K 8664 and K 2411 have been edited separately here.

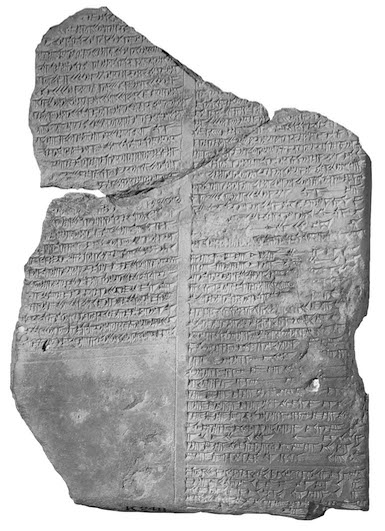

Reverse of K 2411 (text no. 162), a double-column clay tablet with an inscription that Sennacherib had written on the metal plating decorating Marduk's pleasure bed and throne.

Bibliography

163 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003968/]

A fragment from the lower part of a clay tablet that probably comes from Nineveh bears a copy of an inscription that was to be written on stone slabs in the Aššur temple at Aššur. The copy is executed in monumental script (with the exception of line 6'), exactly as the inscription was to go on the original slabs; horizontal ruling lines separate every line of text, with the exception of lines 5'–6'. Only a small portion of the text is preserved; it contains several of Sennacherib's epithets, a boast about the refurbishment of the image of the god Aššur and the perfecting of the rites of Ešarra, and a reference to Sennacherib's father, Sargon II. The text is reminiscent of the so-called "Sin of Sargon" text (see Tadmor, Landsberger, and Parpola, SAAB 3 [1989] pp. 3–52; and Livingstone SAA 3 pp. 77–79 no. 33). The reverse preserves only a four-line subscript, which is written in Neo-Assyrian and "normal (non-monumental) clay script," stating that this inscription was written on alallu-stone slabs that were intended for the king to stand upon.

Access Sennacherib 163 [/rinap/rinap3/Q003968/]

Source:

Bibliography

A. Kirk Grayson & Jamie Novotny

A. Kirk Grayson & Jamie Novotny, 'Nineveh, Part 14', RINAP 3: Sennacherib, The RINAP 3 sub-project of the RINAP Project, 2025 [http://oracc.org/rinap/rinap3/RINAP32TextIntroductions/Nineveh/Part14/]