Aramaic and Hebrew in alphabetic scripts

Akkadian TT was not the only language used in the Assyrian empire. The empire's expansion in the west resulted in the integration of peoples who spoke other Semitic languages TT such as Aramaic and Hebrew. Many of these people were resettled away from their homeland, and by the 8th century BC Aramaic came to be widely used alongside Akkadian as one of the languages of the Neo-Assyrian TT empire.

Leather scrolls and broken pots

Image 1: Detail of a relief TT from the Southwest Palace PGP of Sennacherib PGP in Nineveh PGP , showing two scribes TT : the one on the right is recording information - presumably in Aramaic - on a leather scroll, while his colleague holds a stylus TT and a writing tablet TT . BM 124955. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

These languages used different writing technology from Akkadian TT , which was written using a cuneiform TT script on clay tablets TT . By contrast, both Aramaic and Hebrew employed a much simpler alphabetic script which was based on the writing system used by the Phoenicians PGP . It consisted of just twenty-two characters, each of which represented a single consonant. Documents in Aramaic were typically written in ink on perishable media such as leather and papyrus TT scrolls, or wax-covered tablets made of wood or ivory TT (Image 1). Lists of wine rations found in Nimrud reveal that Aramaean scribes were present at the Assyrian court by the early 8th century BC (1). These specialised scribes were distinguishable not only by their professional equipment but also by the Akkadian term which was used to describe them (sepēru).

Unfortunately the fragile materials used for writing Aramaic do not survive well. This helps explain why the surviving textual record from Assyria is dominated by documents in Akkadian, a language recorded on more durable materials like clay and stone. Nevertheless, Aramaic and Hebrew were sometimes also inscribed on metal or ivory objects, or written in ink on potsherds TT (bits of broken pottery which served as an ancient equivalent of our scrap paper). The surviving evidence is scanty, but it does suggest that Semitic languages, and particularly Aramaic, were used as part of everyday life at all levels of Assyrian society. It also underlines the multi-lingual and multi-cultural nature of the Neo-Assyrian empire at this time.

Alphabetic writing in Assyria

The earliest examples of alphabetic writing in Assyria come from the reign of king Shalmaneser III. Alphabetic markings were found on a number of glazed TT bricks which formed part of the great royal palace in Kalhu known as Fort Shalmaneser. The bricks were also inscribed with the king's name and titles in Akkadian. The letters appear to have been fitters' marks, used by the ancient builders and masons to indicate the position of individual bricks within the overall design. Similar markings can also be seen on ivory inlays uncovered at Nimrud (the so-called Nimrud ivories). Alphabetic letters appear on inconspicuous areas of the carvings, and presumably acted as guides used by craftsmen to put the pieces in the right place (Image 2).

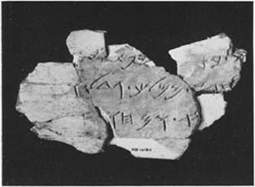

A rare example of a fine Hebrew text from Assyria survives on an ivory fragment, also from Nimrud, which may once have accompanied a votive offering TT (Image 3). The last two lines contain a curse formula designed to deter any would-be vandals:

(May God curse any) of my successors, from great king to private citizen, who may come and destroy this inscription. (2)

Image 3: Ivory fragment TT from room SW 37 in Fort Shalmaneser at Nimrud, inscribed with three lines of 8th century cursive TT Hebrew. The last two lines were apparently part of a curse formula. ND 10150 (3). View large image. Photo: BSAI/BISI.

Among other evidence of bilingualism in the heart of Assyria are seals TT inscribed with short legends in Aramaic. One such seal, discovered in the city of Dur-Šarruken PGP (modern Khorsabad), uses the alphabetic script to identify its owner as "Pan-Aššur-lamur PGP , eunuch TT of Sargon (II) PGP ". We do not know whether Pan-Aššur-lamur also owned a seal in Akkadian, or whether he used the Aramaic seal for a particular purpose such as dealings with Aramaic speakers.

A collection of sixteen bronze TT weights in the shape of a crouching lion, excavated from the Northwest Palace at Nimrud, represents a rare example of bilingual pieces from the 8th and 7th centuries BC. They were inscribed in Akkadian cuneiform as well as in Aramaic (Image 4), and so provide further evidence for the importance of Aramaic at the very centre of the Assyrian empire. In addition, divinatory queries addressed to the sun god, Šamaš PGP , (SAA 4) were often accompanied by a piece of papyrus containing vital details such as the name of the subject of the query. The use of papyrus suggests that this information was recorded in Aramaic rather than Akkadian, but no examples have survived.

Image 4: Bronze weight shaped like a lion, from the Northwest Palace at Nimrud, with an inscription in Aramaic visible on lion's right flank: "Minas TT : 3 by (the standard) of the land; 3 minas of the king". The Akkadian text on the back of the figure reads "Palace of Shalmaneser, king of Assyria; 3 minas of the king". Reign of Shalmaneser V PGP . BM 91226. View large image on British Museum website. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Annotations in Aramaic have been found on economic and legal documents written in Akkadian on clay tablets in the 7th century, presumably added by bilingual scribes fluent in both languages. However, it is clear that the use of Aramaic was subject to some restrictions, as demonstrated in the following letter from Sargon II to Sin-iddina, an official from Ur PGP in southern Babylonia PGP , then a province TT of the Assyrian empire:

[As to what you wrote]: '... if it is acceptable to the king, let me write and send my messages to the king on Aram[aic] parchment TT sheets' – why would you not write and send me messages in Akkadian? Really, the message which you write in it must be drawn up in this very manner – this is a fixed regulation! (SAA 17: 2)

Sargon's message is a clear slap on the wrist to Sin-iddina for overstepping the bounds of propriety. It also shows that royal communication remained rooted in tradition, at least under Sargon II. We have some incidental evidence that Sargon's "fixed regulation" was relaxed under his successors. One letter to Sargon's grandson Sennacherib PGP , for example, mentions an "Aramaic letter which I gave to the king, my lord" (SAA 16: 99). The increasingly frequent use of Aramaic in official communication might also help explain why fewer letters survive from the 7th century BC.

Content last modified: 18 Dec 2019

References

- Kinnier Wilson, J.V., 1972. The Nimrud Wine Lists (Cuneiform Texts from Nimrud 1), London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq (free PDF from BISI, 113 MB). (Find in text ^)

- Millard, A. R., 1962. "Alphabetic Inscriptions on Ivories from Nimrud", Iraq 24, pp. 41-51 (PDF available via JSTOR for subscribers), pp. 47, ND 10150. (Find in text ^)

- Millard, A. R., 1962. "Alphabetic Inscriptions on Ivories from Nimrud", Iraq 24, pp. 41-51 (PDF available via JSTOR for subscribers), pp. Pl. XXIVa. (Find in text ^)

Further reading

- Fales, F. M., 1995. "Assyro-Aramaica: the Assyrian lion-weights", in K. Van Lerberghe and A. Schoors (eds.), Immigration and Emigration within the Ancient Near East: Festschrift E. Lipiński (Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 65), Leuven: Peeters, pp. 33-55 (free PDF from Assyrian Empire Builders, 1.1 MB).

- Fales, F.M., 2000. "The use and function of Aramaic tablets", in G. Bunnens (ed.), Essays on Syria in the Iron Age, Leuven: Peeters, pp. 89-124.

- .

- Millard, A. R., 1962. "Alphabetic Inscriptions on Ivories from Nimrud", Iraq 24, pp. 41-51 (PDF available via JSTOR for subscribers).

- Millard, A., 2008. "Aramaic at Nimrud", in J.E. Curtis, H. McCall, D. Collon and L. al-Gailani Werr (eds.), New Light on Nimrud: Proceedings of the Nimrud Conference 11th-13th March 2002, London: British Institute for the Study of Iraq, pp. 267-270 (free PDF from BISI, 22 MB).

- Naveh, J., 1979-1980. "The Ostracon from Nimrud: an Ammonite name-list", Maarav 2, pp. 163-171.

- Segal, J.B., 1957. "An Aramaic ostracon from Nimrud", Iraq 19, pp. 139-145 (PDF available via JSTOR for subscribers).

- Tadmor, H., 1991. "On the role of Aramaic in the Assyrian empire", in M. Mori, H. Ogawa and M. Yoshikawa (eds.), Near Eastern Studies Dedicated to H.I.H. Prince Takahito Mikasa on the Occasion of his Seventy-Fifth Birthday, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 419-426.

Silvie Zamazalová

Silvie Zamazalová, 'Aramaic and Hebrew in alphabetic scripts', Nimrud: Materialities of Assyrian Knowledge Production, The Nimrud Project at Oracc.org, 2019 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/nimrud/ancientkalhu/thewritings/aramaichebrew/]